NBTHK SWORD JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 713 June, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

Latest Japanese Sword Catalogue

! Antique Japanese Swords For Sale As of December 23, 2012 Tokyo, Japan The following pages contain descriptions of genuine antique Japanese swords currently available for ownership. Each sword can be legally owned and exported outside of Japan. Descriptions and availability are subject to change without notice. Please enquire for additional images and information on swords of interest to [email protected]. We look forward to assisting you. Pablo Kuntz Founder, unique japan Unique Japan, Fine Art Dealer Antiques license issued by Meguro City Tokyo, Japan (No.303291102398) Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Upcoming Sword Shows & Sales Events Full details: http://new.uniquejapan.com/events/ 2013 YOKOSUKA NEX SPRING BAZAAR April 13th & 14th, 2013 kitchen knives for sale YOKOTA YOSC SPRING BAZAAR April 20th & 21st, 2013 Japanese swords & kitchen knives for sale OKINAWA SWORD SHOW V April 27th & 28th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN OKINAWA KAMAKURA “GOLDEN WEEKEND” SWORD SHOW VII May 4th & 5th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN KAMAKURA NEW EVENTS ARE BEING ADDED FREQUENTLY. PLEASE CHECK OUR EVENTS PAGE FOR UPDATES. WE LOOK FORWARD TO SERVING YOU. Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Index of Japanese Swords for Sale # SWORDSMITH & TYPE CM CERTIFICATE ERA / PERIOD PRICE 1 A SADAHIDE GUNTO 68.0 NTHK Kanteisho 12th Showa (1937) ¥510,000 2 A KANETSUGU KATANA 73.0 NTHK Kanteisho Gendaito (~1940) ¥495,000 3 A KOREKAZU KATANA 68.7 Tokubetsu Hozon Shoho (1644~1648) ¥3,200,000 4 A SUKESADA KATANA 63.3 Tokubetsu Kicho x 2 17th Eisho (1520) ¥2,400,000 -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

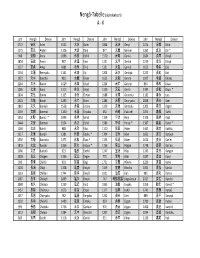

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Apotheosis, Sacred Space, and Political Authority in Japan 1486-1599

QUAESTIONES MEDII AEVI NOVAE (2016) THOMAS D. CONLAN PRINCETON WHEN MEN BECOME GODS: APOTHEOSIS, SACRED SPACE, AND POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN JAPAN 1486-1599 In 1486, the ritual specialist Yoshida Kanetomo proclaimed that Ōuchi Norihiro was the Great August Deity of Tsukiyama (Tsukiyama daimyōjin 築山大明神), and had this apotheosis sanctioned by Go-Tsuchimikado, the emperor (tennō 天皇) of Japan. Ōuchi Norihiro would not seem to be a likely candidate for deifi cation. Although he was an able administrator, and a powerful western warlord, he left few traces. Save for codifying a few laws, and promoting international trade, his most notable act was the rebellion that he initiated against the Ashikaga, the shoguns, or military hegemons of Japan, in the last weeks of his life. Early in this campaign, Norihiro succumbed to illness and died on a small island in Japan’s Inland Sea, leaving his son Masahiro to continue the confl ict against the Ashikaga. This deifi cation, which was formalized some two decades after Norihiro’s demise, was in and of itself not something unique. Japan’s emperors had long been known to have sacerdotal authority, with several sovereigns in the 7th century being referred to as manifest deities (akitsumigami 現神), although this moniker fell out of favor in the 8th century1. To be made a god, the court and its constituent ritual advisors had to recognize one as such. The court and its offi cials, who had long asserted the authority to bestow ranks and titles to gods, could transform men, most notably those who died with a grudge, into gods as well. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135 -

Genji Goes West: the 1510 Genji Album and the Visualization of Court and Capital Melissa Mccormick

Genji Goes West: The 1510 Genji Album and the Visualization of Court and Capital Melissa McCormick Th e recent.ly rediscovered album illusu·ating the .Japanese ·'scenes in an d arou nd Lhe capital" that began to appea r from elevemh -cen tu1)' courtly classic The TalP of Ceuji in the collec t.11e sixteenth century on. tion of the Harvard Univer sity Art Mu ·eu ms grea tly e nhan ces [n co mbin ation, the thr ee sections described above bring our und erstanding of elite lite rary and art istic cu ltu re in late into focus the imp orta nce or the Harvard CPnji Album ror an med ieval J apan (Fig. J). The Harvard Cenji Album, dar.ed to under stan din g of medieval J apanese painting and cultur e. 1510, repr esents not on ly the earliest comp lete album visual In deed, this artwork illLUninates how The Ta/,eof Cenji, for th e izing the most important pro se tale of the Jap anese literaiy first tim e in history, came to embody a kind of time.Jess canon but also one of on ly a handful of dated works by the aristocratic soc ial bod y in the capital, an image that I argue paim er Tosa Mitsun obu (act ive ca. 1462-152 1)- ind eed, o ne wa~ fashion ed and propagated by a . mall group or Kyoto of the few elated cou rt-related painting s of tl,e en tire Mur o- cou rtie rs, po ets, and painte rs and tJ1en "exported'" to outlying ma.chi period (1336-1573). -

Death and Discipleship and Death Kikaku’S

The Rhetoric of Death and Discipleship in Premodern Japan “Horton offers excellent translations of the death accounts of Sōgi and Bashō, along with original answers to two important questions: how disciples of a dying master respond to his death The Rhetoric of in their own relationships and practices and how they represent loss and recovery in their own writing. A masterful study, well Death and Discipleship researched and elegantly written.” —Steven D. Carter, Stanford University in Premodern Japan “Meticulous scholarship and elegant translation combine in this revelatory presentation of the ‘versiprose’ accounts of the deaths of two of the most famous linked-verse masters, Sōgi and Bashō, written by their disciples Sōchō and Kikaku.” —Laurel Rasplica Rodd, University of Colorado at Boulder “Mack Horton has a deep knowledge of the life and work of these two great Japanese poets, a lifetime of scholarship reflect- ed everywhere in the volume’s introduction, translations, and detailed explanatory notes. This is a model of what an anno- tated translation should be.” Horton —Machiko Midorikawa, Waseda University INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES INSTITUTE OF EAST Sōchō’s Death of Sōgi and Kikaku’s Death of Master Bashō H. Mack Horton is Professor of Premodern Japanese Literature in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Berkeley. H. Mack Horton INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES JRM 19 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ● BERKELEY CENTER FOR JAPANESE STUDIES JAPAN RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 19 JRM 19_F.indd 1 9/18/2019 1:43:04 PM Notes to this edition This is an electronic edition of the printed book. -

|P£F. T the LIBRARY Illllm^Ill 099 the UNIVERSITY of BRITISH COLUMBIA

If pr |fe 7950 IBS |p£F. t THE LIBRARY IllllM^ill 099 THE UNIVERSITY Of BRITISH COLUMBIA A List of JAPANESE MAPS of the Tokugawa Era A List of JAPANESE MAPS OF THE TOKUGAWA ERA By GEORGE H. BEANS TALL TREE LIBRARY Jenkintoum 1951 LIBRARY PUBLICATION NO. 23 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 LIST OF MAPS 7 REFERENCES and INDEX 45 LIST OP ILLUSTRATIONS WORLD MAP OF THE SHOHO PERIOD, 1645.2 Frontisp iece PLAN OF EDO, 1664.2 facing page 13 THE TOKAIDO HIGHWAY, [1672.3] 14 PLAN OF KYOTO, 1691.1 16 JAPAN BY RYUSEN, 1697.1 17 SURUGA PROVINCE, 1701.12 18 POLAR HEMISPHERES, 1708.5 20 WORLD MAP BASED ON CHINESE SOURCES, 1710.1 21 HARIMA PROVINCE, I 749.1 22 NAGASAKI, 1764.1 23 JAPAN BY SEKISUI, I 779.1 24 ICELAND AND GREENLAND, 1789.24 27 WORLD MAP FROM DUTCH SOURCES, I 796.1 29 KAMAKURA; ITS SHRINES AND TEMPLES, 1798. I 30 INDIA, 1828.1 34 SURUGA PROVINCE, 1837.13 37 CHINA BY HOKUSAI, 1840. I 38 YOKOHAMA, 1859.1 42 HOKKAIDO, 1859.2 43 A List of JAPANESE MAPS of the Tokugawa Era ABBREVIATIONS p page. We have sometimes used this term to denote one side of a folded sheet but page numbers are used only in connection with books bound in western style. s sheet or sheets. Here used to denote a sheet bound in a book with printing on one side only but folded once and the "free" edges held in a binding. The numbers (not always present) should be sought at the fold where the thumb normally holds the open book. -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

Download the Japan Style Sheet, 3Rd Edition

JAPAN STYLE SHEET JAPAN STYLE SHEET THIRD EDITION The SWET Guide for Writers, Editors, and Translators SOCIETY OF WRITERS, EDITORS, AND TRANSLATORS www.swet.jp Published by Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators 1-1-1-609 Iwado-kita, Komae-shi, Tokyo 201-0004 Japan For correspondence, updates, and further information about this publication, visit www.japanstylesheet.com Cover calligraphy by Linda Thurston, third edition design by Ikeda Satoe Originally published as Japan Style Sheet in Tokyo, Japan, 1983; revised edition published by Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, CA, 1998 © 1983, 1998, 2018 Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher Printed in Japan Contents Preface to the Third Edition 9 Getting Oriented 11 Transliterating Japanese 15 Romanization Systems 16 Hepburn System 16 Kunrei System 16 Nippon System 16 Common Variants 17 Long Vowels 18 Macrons: Long Marks 18 Arguments in Favor of Macrons 19 Arguments against Macrons 20 Inputting Macrons in Manuscript Files 20 Other Long-Vowel Markers 22 The Circumflex 22 Doubled Letters 22 Oh, Oh 22 Macron Character Findability in Web Documents 23 N or M: Shinbun or Shimbun? 24 The N School 24 The M School 24 Exceptions 25 Place Names 25 Company Names 25 6 C ONTENTS Apostrophes 26 When to Use the Apostrophe 26 When Not to Use the Apostrophe 27 When There Are Two Adjacent Vowels 27 Hyphens 28 In Common Nouns and Compounds 28 In Personal Names 29 In Place Names 30 Vernacular Style -

The Tale of Genji

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction In the year 1510, at a private residence in the capital ity began even before Murasaki had completed the city of Kyoto, two men raised their wine cups to cel- work, and by the late twelfth century it had become ebrate the completion of an extraordinary project, so widely admired that would-be poets and littera- an album of fi fty-four pairs of calligraphy and paint- teurs were advised to absorb its lessons. The Tale of ing leaves representing each chapter of Japan’s most Genji quickly became a fi xture of the Japanese liter- celebrated work of fi ction, The Tale of Genji. One of ary canon and centuries later joined the canon of the men, the patron of the album Sue (pronounced world literature. With its length (over 1,300 pages Sué) Saburō, would take it back with him to his home in the most recent English translation), complexity, province of Suō (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture), sophisticated writing style, development of char- on the western end of Japan’s main island. Six years acter and plot, realistic representation of historical later, in 1516, the album leaves would be donated time and place, ironic distance, and subplots that to a local temple named Myōeiji, where the work’s extend thematically across the entire work, it meets traceable premodern history currently ends. In 1957 every criterion that is generally used to distinguish it came into the possession of Philip Hofer (1898– novels from other forms of literature.