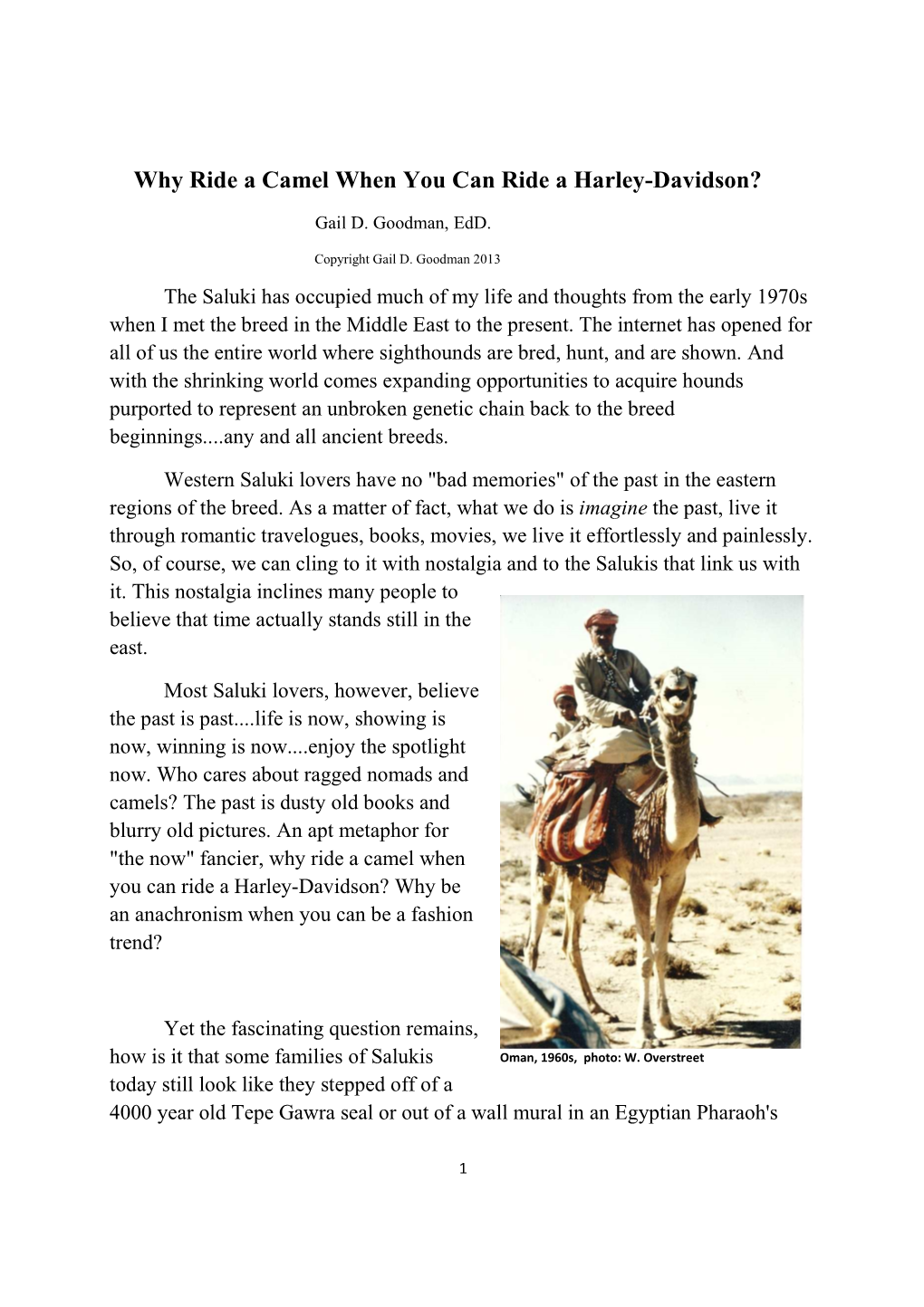

Why Ride a Camel When You Can Ride a Harley-Davidson?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

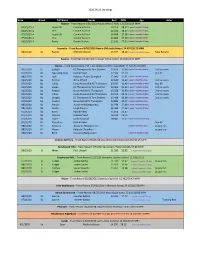

AWARD WINNERS for 2020

AWARD WINNERS for 2020: Place Call name # competing / Owner Time in Sec MPH 2020 Afghan Hounds 3 1st Jeopardy Connie Sullivan 14.319 28.57 2nd Jerzi Connie Sullivan 14.530 28.15 3rd Feniq Deann Britton 15.141 27.02 2020 Azawakh 1 1st Ramisi Michelle Bisbee 14.497 28.22 New Record 2020 Borzoi 17 1st IndyGo KC Thompson & Tom Golcher 12.420 32.94 2nd Ogon (Og Win) Rachel Veed 12.586 32.50 3rd Jack Rebecca Peters-Campbell 12.943 31.61 2020 Greyhound NGA 1 1st Mixer Paul Utesch 11.509 35.55 2020 Greyhound AKC 2 1st Gidget Jackie Gaithe 11.533 35.47 2nd Cashew Susan Visocchi 15.451 26.48 2020 IG 1 1st Sonnie Jennifer Bolton 23.422 17.47 2020 Saluki 1 1st Syan Michelle Bisbee 14.550 28.12 2020 Silken Windhounds 10 1st Chili Barbara Davis (Tim) 13.145 31.12 2nd Walker R. Lynn Schell & Victor Whitlock 13.277 30.81 3rd Azuma Megan Elizabeth 13.353 30.64 2020 Whippet 7 1st Dylan Cathy Day 12.201 33.53 2nd Taco Cole Joyce 12.593 32.49 3rd Olive Krista Bozlinski 12.991 31.49 2020 Whippet Race 4 1st Grizzly Isaac Ben-Joseph 11.760 34.79 2nd Gator Carrie Burns 11.799 34.67 3rd Tesla Carrie Burns 12.565 32.56 2020 Longdog 1 1st Fleta Steven Arpad 12.523 34.47 New Record 2020 Lurcher 3 1st Frenzy Heather Haag 14.508 28.20 2nd Reuben Heather Haag 14.791 27.66 3rd Kaila Montana Johnson 16.436 24.89 2020 Vietnamese Phu Quoc 1 1st Zyra Steve Adams 17.162 23.84 2020 Non-Sighthound Purebreds Herding 3 1st Dutch Shep Bodhi Rebecca Arnold 15.323 26.70 2nd Border Collie Onyx Katelyn Littlefield 15.758 25.96 3rd Aus Cattle Dog Joker Heather Mesmer 16.580 24.67 Herding -

WEST of ENGLAND LADIES' KENNEL SOCIETY SCHEDULE of Benched GENERAL CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (Held Under Kennel Club Limited Rules and Regulations on Group System of Judging)

Compiled by Fosse Data Systems Ltd 01788 860960 • [email protected] • www.fossedata.co.uk WEST OF ENGLAND LADIES' KENNEL SOCIETY SCHEDULE of Benched GENERAL CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (held under Kennel Club Limited Rules and Regulations on Group System of Judging) OPEN TO ALL at THREE COUNTIES SHOWGROUND MALVERN, Worcestershire WR13 6NW (by arrangement with the Three Counties Agricultural Society) on FRIDAY, SATURDAY and SUNDAY 27th, 28th & 29th APRIL 2018 All Judges at this show agree to abide by the following statement: “In assessing dogs, judges must penalise any features or exaggerations which they consider would be detrimental to the soundness, health and well being of the dog.” Guarantors to the Kennel Club: Mrs E. Hughes (Chairman), Hill House, Wotton Road, Iron Acton, Bristol BS37 9XA. Miss H. Wayman (Secretary), 4 Ploughmans Way, Hardwicke, Gloucester GL2 4TF. Tel: 01452 538012 — E-mail: [email protected] Mr P. Davies (Treasurer), 2 Dorset Road, Kingswood, Bristol BS15 1SJ. Mrs J. Gill-Davis, Brook House, Edvin Loach, Bromyard, Hereford HR7 4PW. Miss H. Simper, The White House, Reading Road, Upton Didcot, Oxon OX11 9HP. Mrs S.L. Jakeman Lyheham Lake, Kingham, Oxford OX7 6UJ. O O REDUCED RATES IF ENTERED BY 7th FEBRUARY 2018 O O Postal entries close: WEDNESDAY, 14th MARCH 2018 (Postmark) On-line entries can be made up until midnight on Wednesday, 21st March 2018 Please Note: There will be an additional charge of £1.00 for each first entry made on-line after midnight on Wednesday, 14th March 2018 Postal entries to be sent to Secretary: Miss H. Wayman 4 Ploughmans Way, Hardwicke, Gloucester GL2 4TF Tel: 01452 538012 — E-mail: [email protected] 1 West of England Ladies' Kennel Society Patron: The Duchess of Beaufort President: Mrs C.M. -

WEST of ENGLAND LADIES' KENNEL SOCIETY SCHEDULE of Benched GENERAL CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (Held Under Kennel Club Limited Rules and Regulations on Group System of Judging)

Compiled by Fosse Data Systems Ltd 01788 860960 • [email protected] • www.fossedata.co.uk WEST OF ENGLAND LADIES' KENNEL SOCIETY SCHEDULE of Benched GENERAL CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (held under Kennel Club Limited Rules and Regulations on Group System of Judging) OPEN TO ALL at THREE COUNTIES SHOWGROUND MALVERN, Worcestershire WR13 6NW (by arrangement with the Three Counties Agricultural Society) on FRIDAY, SATURDAY and SUNDAY 26th, 27th & 28th APRIL 2019 All Judges at this show agree to abide by the following statement: “In assessing dogs, judges must penalise any features or exaggerations which they consider would be detrimental to the soundness, health and well being of the dog.” Guarantors to the Kennel Club: Mrs E. Hughes (Chairman), Hill House, Wotton Road, Iron Acton, Bristol BS37 9XA. Miss H. Wayman (Secretary), 4 Ploughmans Way, Hardwicke, Gloucester GL2 4TF. Tel: 01452 538012 — E-mail: [email protected] Mr P. Davies (Treasurer), 2 Dorset Road, Kingswood, Bristol BS15 1SJ. Mrs P. Gregory, Mapalyn, 5 Radnor Park, Malmesbury, Wilts SN16 0HE. Mrs J. Daws, 34 Westbury Road, Cheltenham GL53 9EW. Mrs C. Wareing, 22 Two Hedges Road, Bishop Cleeve, Cheltenham GL52 5DT. O O REDUCED RATES IF ENTERED BY 6th FEBRUARY 2019 O O Postal entries close: WEDNESDAY, 13th MARCH 2019 (Postmark) On-line entries can be made up until midnight on Wednesday, 20th March 2019 Please Note: There will be an additional charge of £1.00 for each first entry made on-line after midnight on Wednesday, 13th March 2019 Postal entries to be sent to Secretary: Miss H. Wayman 4 Ploughmans Way, Hardwicke, Gloucester GL2 4TF Tel: 01452 538012 — E-mail: [email protected] 1 West of England Ladies' Kennel Society Patron: The Duchess of Beaufort President: Mrs C.M. -

Dachtoberfest 2019

Washington Metro Dachtoberfest Foundation WASHINGTON METRO (WMDF), a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, raises AWARENESS and EDUCATES dog DACHTOBERFEST owners about serious veterinary health FOUNDATION issues so they can anticipate the financial commitment of pet ownership, be proactive in their pet’s care, and understand the essential importance of preventive care making pet owners better health ADVOCATES for their pets. A pet owner’s ability to recognize symptoms Washington Metro DachtoberFest of potential life threatening health issues Foundation, formed in 2013, is a such as Intervertebral Disc Disease, seizure 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and epilepsy, obesity, Cushing’s disease, whose mission is to raise awareness dental disease and behavioral matters can lead to earlier intervention and veterinary and educate owners of dachshunds care. and other long back breeds about Intervertebral Disc Disease* and Increased knowledge and proactivity in a health issues common to these pets health results in healthier and happier breeds. pets, opens alternatives to euthanasia and reduces the number of dogs that are * Breeds affected by IVDD include Basset Hound, Beagle, Bull Dog, Chihuahua, Corgi, Cocker surrendered as a result of health related Spaniels, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, issues. Dachshund, French Bulldog, Lhasa Apso, Pekingese, Pomeranian, Poodle and Shih Tzu. It also affects large breed dogs such as Dalmatian, Doberman Pinscher, German Shepard, Labrador Retriever, Pit Bull Terrier and Rottweiler. WASHINGTON METRO DACHTOBERFEST FOUNDATION, INC. DON’T MISS THE FEST P.O. Box 124, Jefferson, MD 21755 WashingtonMetroDachtoberFest.org DACHTOBERFEST 2019 …and they’re off! [email protected] SATURDAY OCTOBER 5, 2019 a 501(c)3 non-profit organization FREDERICK, MD Tax ID 46-2452393 All donations are fully tax deductible as permitted by law. -

Fall 2007 Speaking of Adoptions

Eagle, adopted by Dan and Lauren Emery of North Yarmouth, Me. Lauren Emery cgtuagaztne Regular Departments The Ivbgazine for Greyhound Adopters. O wners. and Fr iends Vol. 12; No. J Fa ll 2007 2 Editorial Comments 15 House Call s Spit That Out! COllllllon household 3 Your Letters items can be dangerous to your Greyhound. Jim Bade r, DVM 8 News 20 Greyhound Humor 11 Reviews Ron Hevener's High Stakes and Erich 24 Second Look R. Sysak's Dog Catcher. Reviewed by Connecticut Greyhound Adoption - Front Cover Credi t; Felicia Bryce One Year Later. Eliza Nardone and Three-year old Reese (Oeglawn Areesh) lives with his adoptive owner, Wi ll Shumaker, in Lori Floyd Tampa , Fla . Will enjoys photographing 13 Hero Hound Greyhounds and is always on the alert fo r Barley and the Bear. A G reyhound 47 You're Invited inte resting poses . He fou nd one. kicks an uninvited houseg llesr to the Back Cover Credit: curb. Ann De ren ~ Lc\\'i s 49 Marketplace Peatie and Bebe, ado pted by Tricia Olson of Memphis, Tenn . 61 In Memoriam Fall 2007 Speaking of Adoptions 28 Spent: An Adoption Group's First Year. North Coast Greyhound Connection comes up with creative solutions to fin ancial challenges. Sandra Augugliaro 32 "Greyhounds Have Taken Over My Life" - The Birth of Minnesota Greyhound Rescue. Jennifer Komatsu 36 Getting Started -Greyhound Pets of America/South Alabama. Darla Dean, Ann Bollens, and Gwen Gay 40 Say ing Goodbye: The Closing of an Adoption Group. A Place for Us Greyhound Adoption ceases operations. -

2020 ZASSC Standings Date Breed Call Name Owner Best MPH Age

2020 ZASSC Standings Date Breed Call Name Owner Best MPH Age Notes Afghan - Track Record 9/30/2013 Hobbi (Mike O'Neil) 13.180/31.04 MPH 01/25/20 A Jeopardy Connie Sullivan 14.319 28.57 2 years 8 months 19 days 01/25/20 A Jerzi Connie Sullivan 14.530 28.15 8 years 0 months 25 days 07/05/20 A Jeopardy Connie Sullivan 14.834 27.58 3 years 1 months 29 days 07/05/20 A Jerzi Connie Sullivan 14.882 27.49 8 years 6 months 4 days 01/25/20 A Feniq Deann Britton 15.141 27.02 2 years 8 months 19 days Azawakh - Track Record 8/01/2020 Ramisi (Michele Bisbee ) 14.497/28.22 MPH 08/01/20 Az Ramisi Michelle Bisbee 14.497 28.22 2 years 10 months 10 days New Record Basenji - Track Record 08/12/17 Cooper (Mike Carter) 16.690/24.51 MPH Borzoi - Track Record 08/27/16 T-Pet (Rebecca Peters Campbell) 11.346/36.06 MPH 01/25/20 Bz IndyGo KC Thompson & Tom Golcher 12.420 32.94 3 years 6 months 30 days 2nd run cert 07/05/20 Bz Ogon (Og Win) Rachel Veed 12.586 32.50 Box #2 08/01/20 Bz Jack Rebecca Peters-Campbell 12.943 31.61 2 years 2 months 18 days 01/25/20 Bz Katrina Anne O'Neill 12.945 31.60 5 years 3 months 0 days 2nd run cert 07/05/20 Bz Lolita Linda Pocurull & KC Thompson 13.027 31.40 2 years 0 months 29 days Box #2 01/25/20 Bz Logan KC Thompson & Tom Golcher 13.063 31.32 1 years 7 months 19 days 2nd run cert 01/25/20 Bz Fireball Dawn Hall & KC Thompson 13.238 30.90 3 years 6 months 29 days 2nd run cert 01/25/20 Bz Lolita Linda Pocurull & KC Thompson 13.323 30.71 1 years 7 months 19 days 2nd run cert 01/25/20 Bz Langley KC Thompson & Tom Golcher 13.468 30.38 -

Primitive and Aboriginal Dog Society

Kuzina Marina 115407, Russia, Moscow, mail-box 12; +10-(095)-118-6370; Web site: http://www.pads.ru; E-mail:[email protected] Desyatova Tatyana E-mail:[email protected] Primitive and Aboriginal Dog Society Dear members of the Russian Branch of Primitive Aboriginal Dogs Society! In this issue we publish the next four articles intended for the Proceedings of the first international cynological conference “Aboriginal Breeds of Dogs as Elements of Biodiversity and the Cultural Heritage of Mankind”. Myrna Shiboleth writes about the ongoing project of many years on the Canaan Dog in Israel. Atila and Sider Sedefchev write about their work with the Karakachan in Bulgaria. Jan Scotland has allowed to republish his article about the history and present situation of the aboriginal population of Kelb tal-Fenek (Rabbit Hunting Dog), erroneously renamed and known as the Pharaoh Hound by show dog fanciers. Almaz Kurmankulov writes about the little known aboriginal sighthound of Kyrgyzstan – theTaigan. The Taigan has become the recognized national breed of Kyrgyzstan. Sincerely yours, Curator of PADS, Vladimir Beregovoy To preserve through education Kuzina Marina 115407, Russia, Moscow, mail-box 12; +10-(095)-118-6370; Web site: http://www.pads.ru; E-mail:[email protected] Desyatova Tatyana E-mail:[email protected] THE CANAAN DOG – BIBLICAL DOG IN MODERN TIMES Myrna Shiboleth THE "DOG OF THE RABBIT" AND ITS IMPORTANCE FOR THE RURAL CULTURE OF MALTA Jan Scotland THE KARAKACHAN DOG. PRESERVATION OF THE ABORIGINAL LIVESTOCK GUARDING DOG OF BULGARIA Atila Sedefchev & -

BPRT Report 3-5-11

Brindle Pattern Research Team Report March 5, 2011 Commissioned by the Saluki Club of America Brian Patrick Duggan, M.A., Chair Casey Gonda, D.V.M., M.S. Lin Hawkyard © 2011 the authors and the Saluki Club of America, and may not be reproduced in part or whole without permission of the copyright holders. All rights reserved. Saluki Club of America: Brindle Pattern Research Team Report 3/5/11 Table of Contents I. Introduction 4 II. Acknowledgements 4 III. Abstract 4 IV. Methodology 4 V. Definition of Evidence 5 PART I: Research Question #1: Was the pattern brindle acknowledged and accepted by Saluki authorities in the time of the 1923 English and 927 American Standards? 5 VI. Creation of the 1923 Standard & the Meaning of “Colour” 6 A. “Colour” 6 B. Describing What They Saw C. Defining & Explaining the Colors 6 D. The 1923 Standard: Collaboration, Latitude, & Subsequent Changes 7 E. Arab Standards 8 F. Registration Liberality 8 G. The American Saluki Standard 8 VII. The Evidence For Brindle Salukis in the Time of the Standard 9 A. KC & AKC Brindle Registrations 9 B. Brindle Text References 12 a. Major Count Bentinck 12 b. Miss H.I.H. Barr 13 c. Mrs. Gladys Lance 13 d. The Honorable Florence Amherst 14 e. Mrs. Carol Ann Lantz 16 f. Saluki Experts on the Variety of “Colour” in the Saluki 16 g. SGHC, SCOA, & AKC Notes on Colors Not Listed in the Standard 18 VIII. The Evidence Against Brindle Salukis in the Time of the Standard 20 A. Text References 20 a. -

LEVRIERI E SEGUGI PRIMITIVI Indice

LEVRIERI E SEGUGI PRIMITIVI Indice — Introduzione........................................................................................ pag. 9 — I levrieri ............................................................................................. pag. 11 – Levriero afgano: - Levriero afgano da esposizione a pelo lungo............................... pag. 15 - Bakhmul o Makhmal Tazi o Horský............................................ pag. 20 (levriero afgano aborigeno a pelo lungo) - Khalag Tazi (levriero afgano aborigeno a pelo frangiato) ............ pag. 22 - Luchak Tazi (levriero afgano aborigeno a pelo corto) o Stepní.... pag. 24 – Levriero arabo (Africa del Nord/Magreb): - Sloughi (pelo corto)................................................................... pag. 26 – Levriero croato: - Starohrvatski Hrt...................................................................... pag. 30 – Levriero del Kazakhstan (Khazakh Tazi o Crymka): - Khazakh Tazi o Crymka..............................................................pag. 33 - Kumai Tazi (pelo frangiato).........................................................pag. 36 - Dzorhghak Tazi (pelo corto) ...................................................... pag. 38 – Levriero del Kyrgzstan: - Taigan o Kyrgyzskaya Borzaya Taigan (pelo lungo).................... pag. 40 – Levriero del Mali (Africa centrale/Mali): - Azawakh (pelo corto)................................................................. pag. 42 – Levriero del Turkmenistan: - Turkmenian Tazi........................................................................pag. -

Midenglishsett.Pdf

22 OUR DOGS November 20 2015 www.ourdogs.co.uk • www.facebook.com/www.ourdogs.co.uk • twitter @ourdogsnews was very willing to donate as did people Junior Stakes - Dog 2nd Mr R & Mrs 23rd; his 2nd CC the following weekend Rhodesian behaved very well for me. at Elnajjar (imp Hungary) has won her for the NEFRA raffle. L Younie Largymore Live To Love You at West England Lab Club under Penny I was listening at ringside to two 7th Green Star and become an Irish A visitor to the show was Elaine, Peter (Shapiron Jokers Wild X Largymore Carpanini and now his 3rd CC and BOB Bernese owners complaining about their Champion. This was achieved at the Irish Forster’s daughter. Her first visit after her Lady Brachla Jw) and shortlisted in the Group under Sue Ridgeback show dogs having hot spots on the neck Schnauzer Club Championship show on Father’s death. That trip is always the Stakes Post Graduate - Bitch Marskell on November 14th. and cheek area... “it's hormonal, isn’t it?” October 26th under Judge Paul Hanna, hardest when you have lost someone 3rd Mrs J O'neill Glenlewis The Dog RCC went to another very With only one more Champ Show to look Wash the area with hibiscrub, dry well, Amin reports Freda also got Best of close to your heart and that applies to our Constellation promising yellow youngster from Junior, forward to this year, we have a few Open use a cover of horse blue, keep him out - Breed and Reserve Best in Show. -

Sussex Longdog Association Show Saturday 3 & Sunday 4 October 2015

2015 AUTUMN SHOW & GAME FAIR SUSSEX LONGDOG ASSOCIATION SHOW SATURDAY 3 & SUNDAY 4 OCTOBER 2015 Judging commences at 12.00noon Entry fee: £2.00 per dog per class Prizes: Rosettes 1st – 4th place SCHEDULE OF CLASSES CLASS CLASS Class 1 Rough Coated Puppy 6 to 12 months open to Lurchers Class 2 Smooth Coated Puppy 6 to 12 months open to Lurchers, Greyhounds and Whippets Class 3 Best Puppy from classes 1 and 2 Class 4 Smooth Lurcher dog and bitch under 21” Class 5 Rough Lurcher dog and bitch under 21” Class 6 Smooth Lurcher dog and bitch 21” to under 24” Class 7 Rough Lurcher dog and bitch 21” to under 24” Class 8 Smooth Lurcher dog and bitch 24” and over Class 9 Rough Lurcher dog and bitch 24” and over Class 10 Purebred Greyhound dog and bitch Class 11 Purebred Whippet dog and bitch Please note Puppies (i.e. dogs less than 12 months) are NOT eligible to be shown in adult classes. Also, if there are a large number of dogs in classes 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 & 12 we will split dog and bitch into two classes on the day. Please make sure your dog is entered in the correct class. If you are in any doubt please have your dog measured by a Sussex Longdog Association committee member to avoid disappointment. CLASS Class 12 Best Rescue/Rehomed Lurcher, Greyhound or Whippet Class 13 Child Handler open to children under 14 years of age Class 14 Best Pair mix or match Class 15 Veteran Lurcher, Whippet or Greyhound 7 years or older Class 16 Any Sighthound (not separately classified) Class 17 Supreme Champion open to winners of classes 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 ENTRIES TAKEN ON THE DAY. -

Levrieri E Segugi Primitivi

LEVRIERI E SEGUGI PRIMITIVI ETNOGEOGRAFIA DI TUTTE LE RAZZE CANINE DEL MONDO CHE INSEGUONO LA PREDA A VISTA SECONDA EDIZIONE RIVEDUTA E AMPLIATA Autore: Mario Canton Antonio Crepaldi Editore INDICE — Introduzione.............................................................................................. pag. 9 — Introduzione alla seconda edizione e ringraziamenti ............................... pag. 10 — Levrieri .................................................................................................... pag. 13 – Levriero Afgano: - Levriero Afgano da esposizione a pelo lungo ................................. pag. 17 - Bakhmul o Makhmal ...................................................................... pag. 22 (levriero afgano aborigeno a pelo lungo) - Khalag Tazi (levriero afgano aborigeno a pelo frangiato) .............. pag. 24 - Luchak Tazi (levriero afgano aborigeno a pelo corto) o Stepní ..... pag. 26 – Levriero arabo (Africa del Nord/Magreb): - Sloughi (pelo corto) ....................................................................... pag. 28 – Levriero croato: - Starohrvatski Hrt .......................................................................... pag. 32 – Levriero del Kazakhstan (Khazakh Tazi o Crymka): - Khazakh Tazi o Crymka ................................................................. pag. 35 - Kumai Tazi (pelo frangiato) ............................................................ pag. 38 - Dzorhghak Tazi (pelo corto) .......................................................... pag. 39 – Levriero del