BPRT Report 3-5-11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNA Suggests Beginnings of Basenji Breed

Course #103 Basenji Timeline Basenji University “Preserving Our Past and Educating Our Future” DNA Suggests Beginnings of Basenji Breed Quotes from this paper which appeared in SCIENCE, 21 May 2004 VOL 304 www.sciencemag.org Genetic Structure of the Purebred Domestic Dog Heidi G. Parker,1,2,3 Lisa V. Kim,1,2,4 Nathan B. Sutter,1,2 Scott Carlson,1 Travis D. Lorentzen,1,2 Tiffany B. Malek,1,3 Gary S. Johnson,5 Hawkins B. DeFrance,1,2 Elaine A. Ostrander,1,2,3,4* Leonid Kruglyak1,3,4,6 We used molecular markers to study genetic … relationships in a diverse collection of 85 domestic The domestic dog is a genetic enterprise dog breeds. Differences among breeds accounted unique in human history. No other mammal has for (30% of genetic variation. Microsatellite enjoyed such a close association with humans genotypes were used to correctly assign 99% of over so many centuries, nor been so substantially individual dogs to breeds. Phylogenetic analysis shaped as a result. A variety of dog morphologies separated several breeds with ancient origins from have existed for millennia and reproductive the remaining breeds with modern European isolation between them was formalized with the origins. We identified four genetic clusters, which advent of breed clubs and breed standards in the predominantly contained breeds with similar mid–19th century. Since that time, the geographic origin, morphology, or role in human promulgation of the “breed barrier” rule—no dog activities. These results provide a genetic may become a registered member of a breed classification of dog unless both its dam and sire are registered Basenji University #103 Basenji Timeline 1 members —has ensured a relatively closed genetic separated the Basenji, an ancient African breed. -

MAJORCA MASTIFF Official UKC Breed Standard Guardian Dog Group ©Copyright 2006, United Kennel Club

MAJORCA MASTIFF Official UKC Breed Standard Guardian Dog Group ©Copyright 2006, United Kennel Club head, which is much greater in circumference in males than in females. CHARACTERISTICS Quiet by nature, but when challenged the Majorca Mastiff can be courageous and brave. He is at ease with people and devoted to his master. He is an excellent watch and guard dog, very self assured. HEAD The head is strong and massive. SKULL - Large, broad and almost square. In males, the circumference of the head is greater than that of the chest measurement taken at the withers. The forehead The goals and purposes of this breed standard include: is broad and flat. The frontal furrow is well defined. The to furnish guidelines for breeders who wish to maintain upper planes of the skull and muzzle are almost parallel. the quality of their breed and to improve it; to advance The stop is strongly defined seen from the side, with a this breed to a state of similarity throughout the world; protruding brow. and to act as a guide for judges. MUZZLE - The muzzle is broad and conical. In profile, it Breeders and judges have the responsibility to avoid resembles a blunt cone with a broad base. The nasal any conditions or exaggerations that are detrimental to bridge is straight. The muzzle is short, one third the the health, welfare, essence and soundness of this length of the skull. The jaw muscles are well developed breed, and must take the responsibility to see that and protruding. The upper lip covers the lower lip to the these are not perpetuated. -

The Kennel Club Breed Health Improvement Strategy: a Step-By-Step Guide Improvement Strategy Improvement

BREED HEALTH THE KENNEL CLUB BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY WWW.THEKENNELCLUB.ORG.UK/DOGHEALTH BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE 2 Welcome WELCOME TO YOUR HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY TOOLKIT This collection of toolkits is a resource intended to help Breed Health Coordinators maintain, develop and promote the health of their breed.. The Kennel Club recognise that Breed Health Coordinators are enthusiastic and motivated about canine health, but may not have the specialist knowledge or tools required to carry out some tasks. We hope these toolkits will be a good resource for current Breed Health Coordinators, and help individuals, who are new to the role, make a positive start. By using these toolkits, Breed Health Coordinators can expect to: • Accelerate the pace of improvement and depth of understanding of the health of their breed • Develop a step-by-step approach for creating a health plan • Implement a health survey to collect health information and to monitor progress The initial tool kit is divided into two sections, a Health Strategy Guide and a Breed Health Survey Toolkit. The Health Strategy Guide is a practical approach to developing, assessing, and monitoring a health plan specific to your breed. Every breed can benefit from a Health Improvement Strategy as a way to prevent health issues from developing, tackle a problem if it does arise, and assess the good practices already being undertaken. The Breed Health Survey Toolkit is a step by step guide to developing the right surveys for your breed. By carrying out good health surveys, you will be able to provide the evidence of how healthy your breed is and which areas, if any, require improvement. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Saw Mill River Kennel Club, Inc. Thursday July 22, 2021

#2021153701 (THURS) #2021164701 (FRI) #2021164702 (SAT) #2021164703 (FRI- RALLY) #2021164704 (SAT-RALLY) COMBINED PREMIUM LIST Show Hours: 7:00am to 6:00 pm CLOSING DATE for entries 12:00 NOON, WEDNESDAY, JULY 7, 2021 at the show Superintendent's Office, after which time entries cannot be accepted, cancelled or substituted, except as provided for in Chapter 11, Section 6 of the Dog Show Rules. Putnam County Veterans Memorial Park- Upper Park 201 Gypsy Trail Rd, Carmel, NY 10512 These events will be held outdoors. NO ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES ARE ALLOWED IN THE PARK The park will charge $5.00 per car for entry to the park. SAW MILL RIVER KENNEL CLUB, INC. THURSDAY JULY 22, 2021 PUTNAM KENNEL CLUB, INC. FRIDAY & SATURDAY, JULY 23 & 24, 2021 SHOW AND GO Same Location - Sunday, July 24, 2021 - Separate Premium List Hudson River Valley Hound Group Show Hudson Highlands Casual Summer Dog Shows We can't beat the heat so we ask that all exhibitors and judges dress accordingly with casual summer clothes. PLEASE SEE DETAILS ON PAGE 6 1 ACCOMMODATIONS Will accept crated dogs Ethan Allen Hotel, 21 Lake Ave., Danbury, CT (pet friendly) . 203-744-1776 Homestead Studio Sites, Fishkill, NY ($25.00 Per Night/Per Pet Fee) . 845-897-2800 Holiday Inn, 80 Newton Rd., Danbury, CT ($15.00 Per Night Pet Fee) . 203-792-4000 Inn at Arbor Ridge, 17 Route 376, Hopewell Junction, NY ($10.00 Pet Fee) . 845-227-7700 Newbury Inn, 1030 Federal Rd., Brookfield, CT ($10.00 per pet per night) . 203-775-0220 Marion Hotel & Suites, 42 Lake Ave Ext., Danbury, CT (per friendly) . -

Bibliography

2406_CH05.qxd 5/19/08 4:49 PM Page 261 Bibliography Unpublished material (i) Official records in the National Archives (N – formerly Public Record Office (PRO)): Records of the British Council (BW) BW 49/13 BW 49/17 Representative’s Annual Reports BW 82/9 British Council Quarterly Reports Records of the Colonial Office CO 730 Original Correspondence Iraq Records of the Foreign Office (FO): FO 60 General Correspondence Persia before 1906. FO 248 Embassy and Consulates General Correspondence, Iran (formerly Persia) FO 251 Consulates and Legations, Iran (formerly Persia): Miscellanea. FO 366 Record’s of the Chief Clerk’s Department. FO 371 Political Departments: General Correspondence from 1906. FO 424 Confidential Print, Turkey. FO 881 Confidential Print Numerical Series. FO 918 Ampthill Mss. Records of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) FCO Services, Croydon: Property Management Department Register of Overseas Properties Vol. 1 Records of the Office of Works (WORK) Work 10 (ii) Records of the Government of India in the British Library India Office Records (IOR) Letters/Political and Secret (L/PS) EUR F 111/156, Curzon collection mss. MSS Eur. F111/531, Summary of the Principle events and measures of the Viceroyalty of Lord Curzon in the Foreign Department, 1 January 1899–April 1904: Volume IV Persia and the Persian Gulf 1907. 2406_CH05.qxd 5/19/08 4:49 PM Page 262 262 BIBLIOGRAPHY P381 Bombay Political Proceedings Introduction to East India Company correspondence on G/29 in the Old India Office, British Library. (iii) Records of the British Embassy Muscat British Embassy, Muscat file 3/TIME/M of 3 October 1993 et seq. -

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

Dog Breeds Pack 1 Professional Vector Graphics Page 1

DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 1 Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Aidi Airedale Terrier Akbash Akita Inu Alano Español Alaskan Klee Kai Alaskan Malamute Alpine Dachsbracke American American American American Akita American Bulldog Cocker Spaniel Eskimo Dog Foxhound American American Mastiff American Pit American American Hairless Terrier Bull Terrier Staffordshire Terrier Water Spaniel Anatolian Anglo-Français Appenzeller Shepherd Dog de Petite Vénerie Sennenhund Ariege Pointer Ariegeois COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 2 Armant Armenian Artois Hound Australian Australian Kelpie Gampr dog Cattle Dog Australian Australian Australian Stumpy Australian Terrier Austrian Black Shepherd Silky Terrier Tail Cattle Dog and Tan Hound Austrian Pinscher Azawakh Bakharwal Dog Barbet Basenji Basque Basset Artésien Basset Bleu Basset Fauve Basset Griffon Shepherd Dog Normand de Gascogne de Bretagne Vendeen, Petit Basset Griffon Bavarian Mountain Vendéen, Grand Basset Hound Hound Beagle Beagle-Harrier COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 2 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 3 Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bearded Collie Beauceron Bedlington Terrier (Tervuren) Dog (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bergamasco Dog (Laekenois) Dog (Malinois) Shepherd Berger Blanc Suisse Berger Picard Bernese Mountain Black and Berner Laufhund Dog Bichon Frisé Billy Tan Coonhound Black and Tan Black Norwegian -

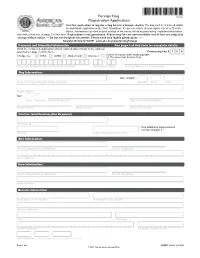

Foreign Dog Registration Application Use This Application to Register a Dog Born in a Foreign Country

Foreign Dog Registration Application Use this application to register a dog born in a foreign country. The dog must be of a breed eligible for individual registration in the AKC® Stud Book. Please use black ink and capital letters to fill in the boxes. Information you omit or print outside of the boxes will delay processing. Important information and instructions are on page 3 of this form. Registration is not guaranteed. Processing fees are nonrefundable and all fees are subject to change without notice. — Do not send original documents. Please send only legible photocopies. — Register Online to SAVE! www.akc.org/register/dog/foreign Payment and Submittal Information See page 3 of this form for complete details Send the completed application and all required attachments to the address specified on page 3 of this form. Processing Fee $ 1 5 0 Check or money order made payable Charge my: VISA AMEX MasterCard Discover to: The American Kennel Club. _ Account Number (do not include dashes) Expiration Date Printed Name of Cardholder Dog Information: Date of Birth: _ _ Dog’s Foreign Registration Number Month Day Year Dog’s Name Sex: Male Female Dog’s Registry Dog’s Country of Birth Dog’s Breed Dog’s Color Dog’s Markings Positive Identification (One Required) Microchip * See Additional Requirements section on page 3. Tattoo DNA Certificate Number Sire Information: Sire’s Registration Number Sire’s Registry Sire’s Name Dam Information: To Be Completed by the Importer of the Dog Dam’s Registration Number Dam’s Registry Dam’s Name Breeder Information Breeder’s First Name Breeder’s Last Name Street Address City Country Email Address Foreign Postal Code _ _ Cell Number (do not include dashes, periods, or spaces) Page 1 of 4 ADIMPT (08/21) v1.0 Edit © 2021 The American Kennel Club AMERICAN KENNEL CLUB® Foreign Dog Registration Application Dog Information Please reenter the dog’s number from page 1 Dog’s Foreign Registration Number Owner Information: To Be Completed and Signed by the First U.S. -

The Arabian Peninsula in Modern Times: a Historiographical Survey of Recent Publications J.E

Journal of Arabian Studies 4.2 (December 2014) pp. 244–74 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21534764.2014.979080 The Arabian Peninsula in Modern Times: A Historiographical Survey of Recent Publications J.E. PETERSON Abstract: Writing on the history of the Arabian Peninsula has grown considerably in recent years and this survey — an updating of an earlier examination — cites and describes the publications in Western languages since 1990 that deal with the Peninsula’s history, historiography, and related subjects. It loosely categorizes the literature according to subject and assesses the state of the art during this time period. It also includes some personal observations of the author on the progress and direction of writing on the Arabian Peninsula. Keywords: Arabian Peninsula, Gulf, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Yemen, history, historiography, country studies, biography, boundaries, military, economic history, social history, cultural history, diplomatic history, foreign policy, Britain, USA, Islam, Wahhabism, Islamic sects, Indian Ocean studies, Hadramawt, Jews in Yemen 1 Introduction In an article published in 1991, I wrote that “The outlines of Arabia’s modern history are well known. It is the underlying firmament that remains terra incognita.”1 To be sure, much of the ter- ritory still remains unknown or unexplored, but, on the positive side, significant inroads have been made over the two decades since then. This survey is an update of that earlier article. The review of recent literature not only reflects an augmentation of publications but a (seemingly paradoxical) broadening and narrowing of focus. I remarked in the earlier essay that much of the literature was descriptive or narrative. -

Gene C Profile Test Results

GeneGc Profile Test Results Horse: ByeMe Champagne Owner: Wendall, Jane Horse and Owner Informaon Horse ByeMe Champagne DOB 6/1/2007 Breed Paint Age 7 Color Classic Champagne Sex S Discipline Western Height 14.2 Registry APHA Reg. Number 12345 Sire Bye Bye Baby Dam Super Champagne Sire Reg. 9058-234 Dam Reg. 4314-334 Comments: Excellent Temperament Owner Wendall, Jane Address Tinseltown Phone 555-1212 City Hollywood, CA E-mail [email protected] Zip Code 91604 GeneGc Profile Test Results Horse: ByeMe Champagne Owner: Wendall, Jane Results Summary Coat Color : ByeMe Champagne has one Black allele and one Red allele making the Base coat appear Black. Also detected were single Champagne and Cream alleles; likely resulUng in a rare Champagne Cream color. One copy of the Frame Overo allele is also detected, indicang underlying white patches (hidden By CH). As a result of single gene copies in each of the following, he has a 50% chance of passing Black or Red, Cream and/or Champagne, AgouU and/or Frame Overo alleles to his offspring. Allele Summary: Aa, Ee, Ch, Cr, LWO/n Traits: ByeMe Champagne is a not a carrier of any known recessive disease genes. CauUon is recommended however, as any mare Bred to him should Be Frame Overo negave as to avoid a 25% chance of foal death (+/+ LWO results in a lethal condiUon at Birth). He may also throw Gaited foals when Bred to Gaited (+) mares. Notes: Please note that your analysis is ongoing and may include some regions marked with an asterisk denoUng the following: * Discovery – This gene detecUon is in the -

Topknot News

Topknot News The newsletter of the Afghan Hound Club of America, Inc. Summer 2009 TAKE THE LEAD — A CONTINUING STORY So to bring you up to the present, the goal of TAKE THE Submitted by Susan Sprung LEAD is to provide financial aid to individuals and families in the purebred dog community who are facing the realities of these life-threatening and often financially devastating For those of you unfamiliar with Take The Lead, I am illnesses. It is our mission to help our fellow fanciers and happy to be able to present an overview. For those who just for the year 2007, we have provided aid in the amount have supported us over the years and continue to do so, of $308,000. In the year 2008, we assisted more clients please consider this a refresher course. than ever and I am advised preliminary figures to date indi- cate we have expended nearly $325,000. TAKE THE As an introduction, TAKE THE LEAD is an organization LEAD is a not-for-profit foundation as designated under formed in 1993 by a small Section 501 (c) (3) of the Internal group of concerned fanciers Revenue Code. All contributions who recognized a dire need to TAKE THE LEAD are tax de- amongst us. Several of the ductible to the full extent allowed founders continue to lead our by the law. In 1995 a permanent organization today. At that restricted Endowment Fund was time in our history, the AIDS formed in order to ensure the epidemic was rampant within future of TAKE THE LEAD.