Primitive and Aboriginal Dog Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Live Weight and Some Morphological Characteristics of Turkish Tazi (Sighthound) Raised in Province of Konya in Turkey

Yilmaz et al. 2012/J. Livestock Sci. 3, 98-103 Live weight and some morphological characteristics of Turkish Tazi (Sighthound) raised in Province of Konya in Turkey Orhan Yilmaz1, Fusun Coskun2, Mehmet Ertugrul3 1Igdir University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science, 76100, Igdir. 2Ahi Evran University, Vocational School, Department of Vetetable and Livestock Production, 40000, Ankara. 2Ankara University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science, 06110, Ankara. 1Corresponding author: [email protected] Office: +90-4762261314/1225, Fax: +90-4762261251 Journal of Livestock Science (ISSN online 2277-6214) 3:98-103 Abstract This study was carried out to determine the distributions of body coat colour and the body measurements of the Turkish Tazi (Sighthound) raised in province of Konya by comparing with some other Sighthound breeds from different regions of Turkey and UK. To this end, a total of 41 (18 male and 23 female) Tazi dogs was analyzed with the Minitab 16 statistical software program using ANOVA and Student’s t-Test. Descriptive statistics for live weight 18.4±0.31, withers height 62.0±0.44, height at rump 62.1±0.50, body length 60.7±0.55, heart girth circumference 63.9±0.64, chest depth 23.1±0.21, abdomen depth 13.9±0.21, chest width 17.4±0.25, haunch width 16.4±0.18, thigh width 22.3±0.26, tail length 45.7±0.37, limb length 38.9±0.31, cannon circumference 10.2±0.11, head length 24.0±0.36 and ear length 12.8±0.19 cm respectively. -

The Karakachan Dog Is One of Europe’S Oldest Breeds

International Karakachan Dog Association Karakachan Dog (Karakachansko Kuche – in Bulgarian) Official Breed Standard The Breed and the breed Standard are registered in 2005 in conformity with Bulgarian Law by: •Ministry of Agriculture and Foods of the Republic of Bulgaria with Resolution of State Commission for animal breeds from 10.08.2005. •Bulgarian Patent Office. Certificate for recognition of native breed № BG 10675 P2 Origin: Bulgaria Synonyms: Ovcharsko kuche, Chobansko kuche, Vlashko kuche, Thracian Mollos, Karakachan Dog, Karakatschan Hund, Chien Karakatschan, Authors of the standard: V. Dintchev, S. Sedefchev, A. Sedefchev – 14. 01. 2000 (with amendments) Date of publication of the first original valid standard: 26.06. 1991, Thracian University, Stara Zagora. Utilization: used as a watch and a guard dog for livestock, houses and a companion for people. Classification FCI: Group 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer- Molossoid breeds- Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs and other breeds. Section 2.2 Molossoid breeds, Mountain type. Without working trial. Brief historical survey: The Karakachan Dog is one of Europe’s oldest breeds. A typical Mollosus, created for guarding its owner’s flock and property, it does not hesitate to fight wolves or bears to defend its owner and his family in case of danger. Its ancestors started forming as early as the third millennium BC. The Karakachan Dog is a descendant of the dogs of the Thracians - the oldest inhabitants of the Balkan peninsula, renowned as stock-breeders, whom Herodotus describes as the most numerous people after the Indian one. The Proto-Bulgarians also played an essential part in the formation of the Karakachan Dog as they brought their dogs with them at the time of their migration from Pamir and Hindukush. -

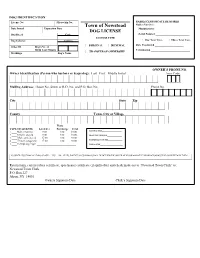

Dog License Application

DOG IDENTIFICATION License No. Microchip No. RABIES CERTIFICATE REQUIRED Rabies Vaccine: Town of Newstead Date Issued Expiration Date Manufacturer __________________________ DOG LICENSE Serial Number __________________________ Dog Breed Code LICENSE TYPE Dog Color(s) Code(s) One Year Vacc. Three Year Vacc. ORIGINAL RENEWAL Date Vaccinated ______________________ Other ID Dog’s Yr. of Birth Last 2 Digits Veterinarian ______________________________ TRANSFER OF OWNERSHIP Markings Dog’s Name OWNER’S PHONE NO. Owner Identification (Person who harbors or keeps dog): Last First Middle Initial Area Code Mailing Address: House No. Street or R.D. No. and P.O. Box No. Phone No. City State Zip County Town, City or Village State TYPE OF LICENSE Local Fee Surcharge Total 1.____Male, neutered 9.00 1.00= 10.00 LICENSE FEE____________________ 2.____Female, spayed 9.00 1.00= 10.00 SPAY/NEUTER FEE_______________ 3.____ Male, unneutered 17.00 3.00= 20.00 4.____ Female, unspayed 17.00 3.00= 20.00 ENUMERATION FEE______________ 5.____Exempt dog Type: ______________________________ TOTAL FEE______________________ _ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IS OWNER LESS THAN 18 YEARS OF AGE? YES NO IF YES, PARENT Owner’s OR GUARDIANSignature SHALL BE DEEMED THE OWNERDate OF RECORD AND THEClerk’s INFORMATION Signature MUST BE COMPLETEDDate BY THEM. Return form, current rabies certificate, spay/neuter certificate (if applicable) and check made out to “Newstead Town Clerk” to: Newstead Town Clerk P.O. Box 227 Akron, NY 14001 _____________________________________ ___________________________________________ Owners Signature/Date Clerk’s Signature/Date OWNER’S INSTRUCTIONS 1. All dogs 4 months of age or older are to be licensed. In addition, any dog under 4 months of age, if running at large must be licensed. -

Dog Breeds Pack 1 Professional Vector Graphics Page 1

DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 1 Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Aidi Airedale Terrier Akbash Akita Inu Alano Español Alaskan Klee Kai Alaskan Malamute Alpine Dachsbracke American American American American Akita American Bulldog Cocker Spaniel Eskimo Dog Foxhound American American Mastiff American Pit American American Hairless Terrier Bull Terrier Staffordshire Terrier Water Spaniel Anatolian Anglo-Français Appenzeller Shepherd Dog de Petite Vénerie Sennenhund Ariege Pointer Ariegeois COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 2 Armant Armenian Artois Hound Australian Australian Kelpie Gampr dog Cattle Dog Australian Australian Australian Stumpy Australian Terrier Austrian Black Shepherd Silky Terrier Tail Cattle Dog and Tan Hound Austrian Pinscher Azawakh Bakharwal Dog Barbet Basenji Basque Basset Artésien Basset Bleu Basset Fauve Basset Griffon Shepherd Dog Normand de Gascogne de Bretagne Vendeen, Petit Basset Griffon Bavarian Mountain Vendéen, Grand Basset Hound Hound Beagle Beagle-Harrier COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 2 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 3 Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bearded Collie Beauceron Bedlington Terrier (Tervuren) Dog (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bergamasco Dog (Laekenois) Dog (Malinois) Shepherd Berger Blanc Suisse Berger Picard Bernese Mountain Black and Berner Laufhund Dog Bichon Frisé Billy Tan Coonhound Black and Tan Black Norwegian -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

Dog” Looks Back at “God”: Unfixing Canis Familiaris in Kornél Mundruczó’S † Film Fehér Isten/White God (2014)

humanities Article Seeing Beings: “Dog” Looks Back at “God”: Unfixing Canis familiaris in Kornél Mundruczó’s † Film Fehér isten/White God (2014) Lesley C. Pleasant Department of Foreign Languages and Cultures, University of Evansville, Evansville, IN 47714, USA; [email protected] † I have had to rely on the English subtitles of this film, since I do not speak Hungarian. I quote from the film in English, since the version to which I have had access does not give the option of Hungarian subtitles. Received: 6 July 2017; Accepted: 13 October 2017; Published: 1 November 2017 Abstract: Kornél Mundruczó’s film Fehér isten/White God (2014) portrays the human decreed options of mixed breed, abandoned dogs in the streets of Budapest in order to encourage its viewers to rethink their relationship with dogs particularly and animals in general in their own lives. By defamiliarizing the familiar ways humans gaze at dogs, White God models the empathetic gaze between species as a potential way out of the dead end of indifference and the impasse of anthropocentric sympathy toward less hierarchical, co-created urban animal publics. Keywords: animality; dogs; film; White God; empathy 1. Introduction Fehér isten/White God (2014) is not the first film use mixed breed canine actors who were saved from shelters1. The Benji films starred mixed breed rescued shelter dogs (McLean 2014, p. 7). Nor is it unique in using 250 real screen dogs instead of computer generated canines. Disney’s 1996 101 Dalmations starred around 230 Dalmation puppies and 20 adult Dalmations (McLean 2014, p. 20). It is also certainly not the only film with animal protagonists to highlight Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody # 2 in its soundtrack. -

Quiz Sheets BDB JWB 0513.Indd

2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write one breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet and receive one point for each correct answer. There’s an extra five points on offer for those that can find correct answers for Q, U, X and Z! A N B O C P D Q E R F S G T H U I V J W K X L Y M Z Dogs for the Disabled The Frances Hay Centre, Blacklocks Hill, Banbury, Oxon, OX17 2BS Tel: 01295 252600 www.dogsforthedisabled.org supporting Registered Charity No. 1092960 (England & Wales) Registered in Scotland: SCO 39828 ANSWERS 2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write a breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet (one point each). Additional five points each if you get the correct answers for letters Q, U, X or Z. Or two points each for the best imaginative breed you come up with. A. Curly-coated Retriever I. P. Tibetan Spaniel Affenpinscher Cuvac Ibizan Hound Papillon Tibetan TerrieR Afghan Hound Irish Terrier Parson Russell Terrier Airedale Terrier D Irish Setter Pekingese U. Akita Inu Dachshund Irish Water Spaniel Pembroke Corgi No Breed Found Alaskan Husky Dalmatian Irish Wolfhound Peruvian Hairless Dog Alaskan Malamute Dandie Dinmont Terrier Italian Greyhound Pharaoh Hound V. Alsatian Danish Chicken Dog Italian Spinone Pointer Valley Bulldog American Bulldog Danish Mastiff Pomeranian Vanguard Bulldog American Cocker Deutsche Dogge J. Portugese Water Dog Victorian Bulldog Spaniel Dingo Jack Russel Terrier Poodle Villano de Las American Eskimo Dog Doberman Japanese Akita Pug Encartaciones American Pit Bull Terrier Dogo Argentino Japanese Chin Puli Vizsla Anatolian Shepherd Dogue de Bordeaux Jindo Pumi Volpino Italiano Dog Vucciriscu Appenzeller Moutain E. -

E O Cial Publication of the Basenji Club of America, Inc

Vol.51 | No. 2 | MAY JUN JUL AUG | 2016 e O cial Publication BULLETINof the Basenji Club of America, Inc. BCOA BULLETIN CONTENTS MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2016 On the cover JAYDA Nailah in That Lil Red Dress For Woodella Bred by: Christine Petersen Owned by: Tom Rabbi e & Charley Donaldson Handled by: Charley Donaldson West of England Ladies Kennel Society (WELKS), Malvern, England 2016. Jayda was awarded Best Any Variety Puppy. Cru s, Birmingham, England 2016. Jayda was awarded Best Of Breed, Best Puppy, and Bitch Challenge Certi cate. Cover Photo: George Waddell, om WELKS show. Photo at right: V.L. Gaskell FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 7 Calendar of Events 20 A LIFETIME MEMBER PROFILE DR. STEVE GONTO 8 About this Issue BY DR. STEVE GONTO, WITH HOLLY HAMILTON 9 Contributors 26 CELEBRATION OF DOGS 10 Letter from the President CRUFTS ENGLAND 1891-2016 12 Training Tips BY ETHEL BLAIR 13 Juniors 30 A JUDGE’S POINT OF VIEW AKC & ASFA LURE COURSING JUDGING BY HOLLY HAMILTON REPORTS 32 SPORTSMANSHIP BY GREGORY ALDEN BETOR 14 Committee Reports 35 VALE JOHN EDWARD VALK 16 Affi liate Club Reports A TRIBUTE 18 Basenji Foundation Stock Applicants BY COLLABORATION cvr2 BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2016) visit us online at www.basenji.org www.facebook.com/basenji.org BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2016) 1 It’s never too late to celebrate your wins (or the cuteness). BULLETIN Let the world know you’re proud of your hound with an ad in the Bulletin. e O cial Publication Best value around. of the Basenji Club of America, Inc. -

Wolves and Livestock

University of Montana ScholarWorks Wolves and Livestock: A review of tools to deter livestock predation and a case study of a proactive wolf conflict mitigation program developed in the Blackfoot Valley, Montana By Peter Douglas Brown Bachelor of Science, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 1998 Professional Paper presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Resource Conservation The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2011 Approved by: Dr. J.B. Alexander Ross Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Don Bedunah, Chair College of Forestry and Conservation Forest Management Dr. Seth M. Wilson, Committee Member Blackfoot Challenge Dr. Matthew McKinney, Committee Member UM School of Law Public Policy Brown, Peter, M.S., May 2011 Resource Conservation Wolves and Livestock: A review of tools to deter livestock predation and a case study of a proactive wolf conflict mitigation program developed in the Blackfoot Valley, Montana Chairperson: Dr. Don Bedunah PhD. Abstract The recent recovery of wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains (NRM) was met with opposition from the ranching communities throughout Montana. This was not surprising, due to the fact that wolves are feared as a predator of livestock and therefore represent a direct economic loss for ranchers that experience depredations by wolves. Wolves are also revered as a native predator that have top down effects upon natural prey species. This in turn affects the web of plants and animals that make up natural ecosystems. This fact, as well as the strong emotional connection that some stakeholders have to wolves creates a tense value laden debate when wolves come into conflict with humans. -

CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation Acknowledgements with Grateful Thanks To: the Kennel Club, Battersea (Dogs & Cats Home) & Prof

CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation Acknowledgements With grateful thanks to: The Kennel Club, Battersea (Dogs & Cats Home) & Prof. Sheila Crispin MA BScPhD VetMB MRCVS for providing diagrams and images Google, for any images made available through their re-use policy Please note that images throughout the Guidance are subject to copyright and permissions must be obtained for further use. Index 1. Introduction 5 2. Conformation 5 3. Legislation 5 4. Impact of poor conformation 6 5. Conformation & physical appearance 6 Eyes, eyelids & area surrounding the eye 7 Face shape – flat-faced (brachycephalic) dog types 9 Mouth, dentition & jaw 11 Ears 12 Skin & coat 13 Back, legs & locomotion 14 Tail 16 6. Summary of Key Points 17 7. Resources for specific audiences & actions they can take to support good dog conformation 18 Annex 1: Legislation, Guidance & Codes of Practice 20 1. Legislation in England 20 Regulations & Guidance Key sections of Regulations & Guidance relevant to CFSG sub-group on dog conformation Overview of the conditions and explanatory guidance of the Regulations 2. How Welfare Codes of Practice & Guidance support Animal Welfare legislation 24 Defra’s Code of Practice for the Welfare of Dogs Animal Welfare Act 2006 Application of Defra Code of Practice for the Welfare of Dogs in supporting dog welfare 3. The role of the CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation in supporting dog welfare 25 CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation 3 Annex 2: Key points to consider if intending to breed from or acquire either an adult dog or a puppy 26 Points -

The Cocker Spaniel by Sharon Barnhill

The Cocker Spaniel By Sharon Barnhill Breed standards Size: Shoulder height: 38 - 41 cm (15 - 16.5 inches). Weight is around 29 lbs. Coat: Hair is smooth and medium length. Character: This dog is intelligent, cheerful, lively and affectionate. Temperament: Cocker Spaniels get along well with children, other dogs, and any household pets. Training: Training must be consistent but not overly firm, as the dog is quite willing to learn. Activity: Two or three walks a day are sufficient. However, this breed needs to run freely in the countryside on occasion. Most of them love to swim. Cocker spaniel refers to two modern breeds of dogs of the spaniel dog type: the American Cocker Spaniel and the English Cocker Spaniel, both of which are commonly called simply Cocker Spaniel in their countries of origin. It was also used as a generic term prior to the 20th century for a small hunting Spaniel. Cocker spaniels were originally bred as hunting dogs in the United Kingdom, with the term "cocker" deriving from their use to hunt the Eurasian Woodcock. When the breed was brought to the United States it was bred to a different standard which enabled it to specialize in hunting the American Woodcock. Further physical changes were bred into the cocker in the United States during the early part of the 20th century due to the preferences of breeders. Spaniels were first mentioned in the 14th century by Gaston III of Foix-Béarn in his work the Livre de Chasse. The "cocking" or "cocker spaniel" was first used to refer to a type of field or land spaniel in the 19th century.