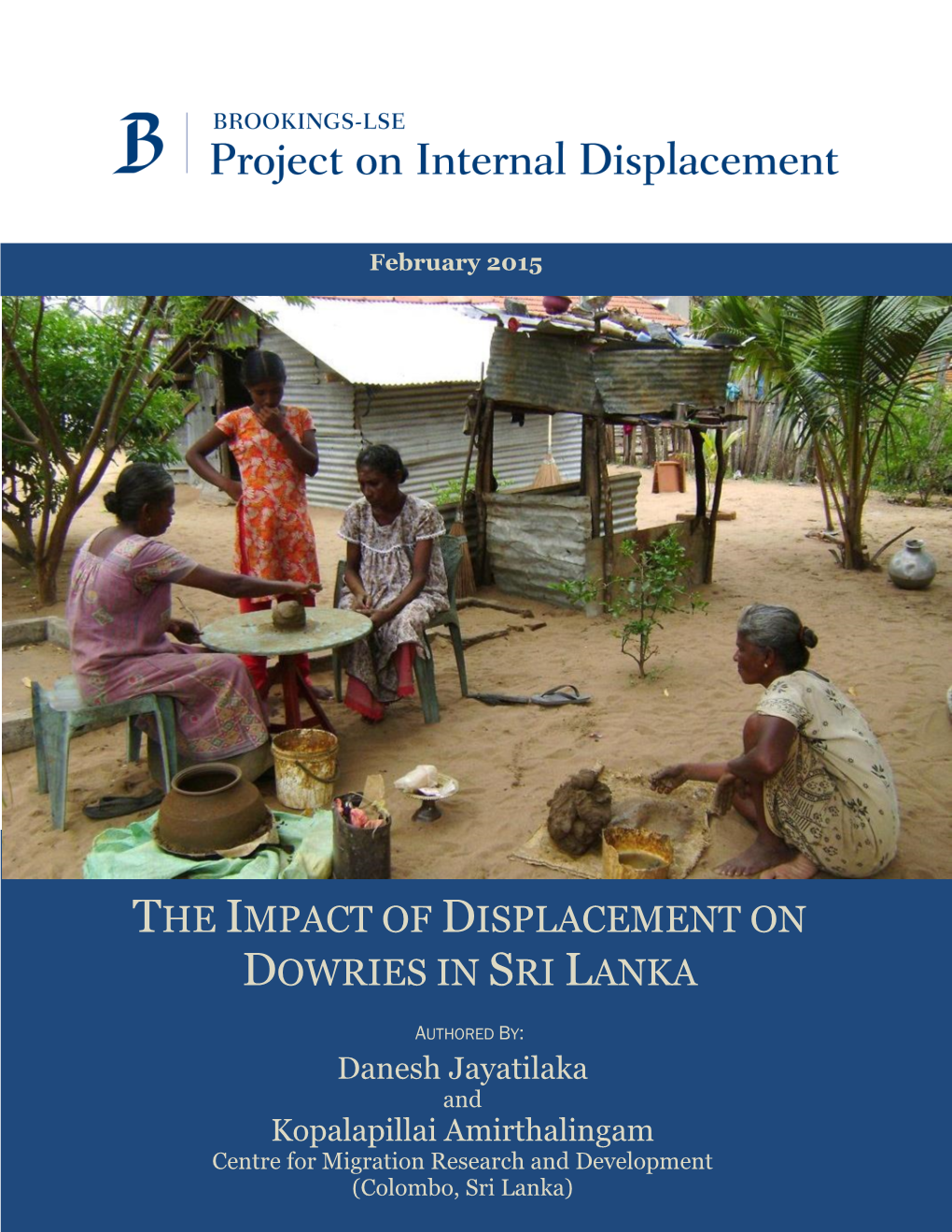

The Impact of Displacement on Dowries in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 3 8 147 - LK PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 21.7 MILLION (US$32 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR A PUTTALAM HOUSING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized JANUARY 24,2007 Sustainable Development South Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 13,2006) Currency Unit = Sri Lankan Rupee 108 Rupees (Rs.) = US$1 US$1.50609 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LTF Land Task Force AG Auditor General LTTE Liberation Tigers ofTamil Eelam CAS Country Assistance Strategy NCB National Competitive Bidding CEB Ceylon Electricity Board NGO Non Governmental Organization CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment NEIAP North East Irrigated Agriculture Project CQS Selection Cased on Consultants Qualifications NEHRP North East Housing Reconstruction Program CSIA Continuous Social Impact Assessment NPA National Procurement Agency CSP Camp Social Profile NPV Not Present Value CWSSP Community Water Supply and Sanitation NWPEA North Western Provincial Environmental Act Project DMC District Monitoring Committees NWPRD NorthWest Provincial Roads Department -

The Case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences 2017 40 (1): 41-52 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/sljss.v40i1.7500 RESEARCH ARTICLE Collective ritual as a way of transcending ethno-religious divide: the case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka# Anton Piyarathne* Department of Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Sri Lanka. Abstract: Sri Lanka has been in the prime focus of national and who are Sinhala speakers, are predominantly Buddhist, international discussions due to the internal war between the whereas the ethnic Tamils, who communicate in the Tamil Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan language, are primarily Hindu. These two ethnic groups government forces. The war has been an outcome of the are often recognised as rivals involved in an “ethnic competing ethno-religious-nationalisms that raised their heads; conflict” that culminated in war between the LTTE (the specially in post-colonial Sri Lanka. Though today’s Sinhala Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a military movement and Tamil ethno-religious-nationalisms appear as eternal and genealogical divisions, they are more of constructions; that has battled for the liberation of Sri Lankan Tamils) colonial inventions and post-colonial politics. However, in this and the government. Sri Lanka suffered heavily as a context it is hard to imagine that conflicting ethno-religious result of a three-decade old internal war, which officially groups in Sri Lanka actually unite in everyday interactions. ended with the elimination of the leadership of the LTTE This article, explains why and how this happens in a context in May, 2009. -

Biosystematic Studies of Ceylonese Wasps, XVII: a Revision of Sri Lankan and South Indian Bembix Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Sphecoidea: Nyssonidae) I

fc Biosystematic Studies of Ceylonese Wasps, XVII: A Revision of Sri Lankan and South Indian Bembix Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Sphecoidea: Nyssonidae) I KARL V. KROMBEIN and J. VAN DER VECHT SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 451 ir SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Socio-Religious Desegregation in an Immediate Postwar Town Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Carnets de géographes 2 | 2011 Espaces virtuels Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon Madavan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 DOI: 10.4000/cdg.2711 ISSN: 2107-7266 Publisher UMR 245 - CESSMA Electronic reference Delon Madavan, « Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town », Carnets de géographes [Online], 2 | 2011, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 07 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 ; DOI : 10.4000/cdg.2711 La revue Carnets de géographes est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon MADAVAN PhD candidate and Junior Lecturer in Geography Université Paris-IV Sorbonne Laboratoire Espaces, Nature et Culture (UMR 8185) [email protected] Abstract The cease-fire agreement of 2002 between the Sri Lankan state and the separatist movement of Liberalisation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was an opportunity to analyze the role of war and then of the cessation of fighting as a potential process of transformation of the segregation at Jaffna in the context of immediate post-war period. Indeed, the armed conflict (1987-2001), with the abolition of the caste system by the LTTE and repeated displacements of people, has been a breakdown for Jaffnese society. The weight of the hierarchical castes system and the one of religious communities, which partially determine the town's prewar population distribution, the choice of spouse, social networks of individuals, values and taboos of society, have been questioned as a result of the conflict. -

A Comparative Investigation of the Self Image and Identity of Sri Lankans

A Comparative Investigation of the Self Image and Identity of Sri Lankans Malathie P. Dissanayake Department of Psychology, West Chester University, West Chester, PA 19383; [email protected] Jasmin Tahmaseb McConatha Department of Psychology, West Chester University, West Chester, PA 19383; [email protected] The current study explores self image and identity of Sri Lankans in different social and cultural settings. It focuses on the role of major social identities in two ethnic groups: Sinhalese (the majority) and Tamils (the minority). Participants consisted of four groups: Sri Lankan Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamils, Sinhalese in USA, and Tamils in Canada. Seven self statement tests, ratings of the importance of major social identities, and eight common identity items under seven social identities were used to examine self identification. Findings suggest that religious identity plays a significant role in Sinhalese, whereas ethnic identity is the most significant in Tamils. All these identity measures suggest that the role of each social identity is different when it associates with different social settings, depending on how individuals value their social identities in particular social contexts. Keywords : Self Image, Ethnic Identity, Sri Lanka 1. INTRODUCTION Self image and identity are central to the ways in which people understand the world. Self image influences thoughts, feelings, behaviors, relationships, goals, and plans across the life- span. Every person has a sense of self, a sense of “who they are”, which is comprised of physical, psychological, and social aspects of his or her life. The self has been described as the internal organization of external roles (Hormuth 1990). Matsumoto and Juang (2004) believe that the self concept is the organization of a person’s psychological traits, attributes, characteristics, and behaviors. -

Newsletter Supporting Communities in Need

NEWSLETTER ICRC JULY-SEPTEMBER 2014 SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES IN NEED Economic security and water and sanitation for the vulnerable Dear Reader, they could reduce the immense economic This year, the ICRC started a Community Conflicts destroy livelihoods and hardships and poverty under which they Based Livelihood Support Programme infrastructure which provide water and and their families are living at present” (para (CBLSP) to support vulnerable communities sanitation to communities. Throughout 5.112). in the Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi districts the world, the ICRC strives to enable access to establish or consolidate an income to clean water and sanitation and ensure The ICRC’s response during the recovery generating activity. economic security for people affected by phase to those made vulnerable by the conflict so they can either restore or start a conflict was the piloting of a Micro Economic The ICRC’s economic security programmes livelihood. Initiatives (MEI) programme for women- are closely linked to its water and sanitation headed households, people with disabilities initiatives. In Sri Lanka today, the ICRC supports and extremely vulnerable households in vulnerable households and communities In Sri Lanka, the ICRC restores wells the Vavuniya district in 2011. The MEI is in the former conflict areas to become contaminated as a result of monsoonal a programme in which each beneficiary economically independent through flooding, and renovates and builds pipe identifies and designs the livelihood sustainable income generation activities and networks, overhead water tanks, and for which he or she needs assistance to provides them clean water and sanitation by toilets in rural communities for returnee implement, thereby employing a bottom- cleaning wells and repairing or constructing populations to have access to clean water up needs-based approach. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Sri Lanka's Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire

Sri Lanka’s Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire Asia Report N°253 | 13 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Northern Province Elections and the Future of Devolution ............................................ 2 A. Implementing the Thirteenth Amendment? ............................................................. 3 B. Northern Militarisation and Pre-Election Violations ................................................ 4 C. The Challenges of Victory .......................................................................................... 6 1. Internal TNA discontent ...................................................................................... 6 2. Sinhalese fears and charges of separatism ........................................................... 8 3. The TNA’s Tamil nationalist critics ...................................................................... 9 D. The Legal and Constitutional Battleground .............................................................. 12 E. A Short- -

Facets-Of-Modern-Ceylon-History-Through-The-Letters-Of-Jeronis-Pieris.Pdf

FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS BY MICHAEL ROBERT Hannadige Jeronis Pieris (1829-1894) was educated at the Colombo Academy and thereafter joined his in-laws, the brothers Jeronis and Susew de Soysa, as a manager of their ventures in the Kandyan highlands. Arrack-renter, trader, plantation owner, philanthro- pist and man of letters, his career pro- vides fascinating sidelights on the social and economic history of British Ceylon. Using Jeronis Pieris's letters as a point of departure and assisted by the stock of knowledge he has gather- ed during his researches into the is- land's history, the author analyses several facets of colonial history: the foundations of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the nineteenth century; the process of Wes- ternisation and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance no. 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land bet- ween coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan dis- tricts. This analysis is threaded by in- formation on the Hannadige- Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families and by attention to the various sources available to the historians of nineteenth century Ceylon. FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS MICHAEL ROBERTS HANSA PUBLISHERS LIMITED COLOMBO - 3, SKI LANKA (CEYLON) 4975 FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 This book is copyright. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

Jaffna District யா��பாண

වාක කායසාධන හා වාතා ව வடாத ெசயலாைக ம கணக அறிைக ANNUAL PERFORMANCE & ACCOUNTS REPORT 2012 දර අෛමනායහ தர அைமநாயக Suntharam Arumainayaham ස් ෙක / සාප அரசாக அதிப/மாவட ெசயலாள Distri ct Secretary / Government Agent ස් ෙක කායාලය மாவட ெசயலக District Secretariat යාපනය ස්කය Jaffna District யாபாண වාක කායසාධන හා වාතාව යාපනය ස්කය 2012 வடாத ெசயலாறறிைக ம கணக அறிைக யாபாண மாவட 2012 Annual Performance and Report on Accounts Jaffna District 2012 Annual Performance and Accounts - 2012 Jaffna District Contents Page no 1.Message from Government Agent / District Secretary- Jaffna ...............................................................................2 2.Introduction of District Secretariat ..........................................................................................................................3 2.1 Vision and Mission Statements ...............................................................................................................3 2.2 Objectives of District Secretariat .............................................................................................................4 2.3 Activities of District Secretariat ..............................................................................................................4 3.Introduction of the District ......................................................................................................................................5 3.1 Borders of the District: ............................................................................................................................6