The Foundations of America's Exceptional Role in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union County

• News • Arts • Entertainment • Classified • Real Estate Union County • Automotive WORRALL COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS THURSDAY, MAY 11,2000 • SECTION B http://www.toca!«ouic&c«ii In their Assembly bill would Comparison of county tax levy, 1997-2000 , m' im IKS Cbmge Berkeley Heights $7,094,341 $7,913,617 18,370,956 $8,551,164 +S180.2O6 own right alter freeholder seats Clark SS,601,807 $5,363,129 $6,139,768 $5,332,667 •$192,899 Cranford S9,026,277 +S123.670 Georg's W. Bush anil Al Gore S9,306,«94 16,904,847 $8,904,607 By Mark Hrywna Gsiwood have one'thing in common. Aftei SI ,377,234 $1,399,666 $1,340,745 tl.346,430 +S7.685 Regional Editor Elizabeth -S370.101 some detours.they both ended up in $15,443,145 $14,674,095 ' $16,041,242 $14,671,141 - Republicans call it betler represen- Fanwood 52,343,375 the some professional field as their $2,423,075 $2,362,294 $2,408,778 •S26.484 tation of the people, bringing govern- ' Hillskle $4,327,759 $4,387,693 •SS.881 famous fathers. S4,4S0,S91 $4,382,012 mem closer to constituents, Demo- • Kenilworth $3,820,427 $3,668,079 $3,722,306 $3,750,619 +$28,313 Following in the footsteps of crats say the GOP is simply trying to Linden $12,343,861 $12,949,977 $13,018,563 $11,455,594 •S1.SS2.9S9 your parent is not that uncommon. overcome Us fuiilliy in recent elec- Mountainside $3,849,955 $4,120,739 $4,114,451 $4,172,760 +$58,309 • Bui for those making the second set tion!: by legislating a teat on the free- New Providence SS.031,291 $6,002,681 (6,091.012 $6,178,234 +S87.222 of prints the experience can be full holder board. -

Winter 2009 Licata Lecture: Michael Novak Calls for Conversation About God

WINTER 2009 LICATA LECTURE: MICHAEL NOVAK CALLS FOR CONVERSATION ABOUT GOD And yet, he told his Pepperdine audi- ence faith is a “real knowledge—a practi- cal kind of knowledge worth trusting one’s life to.” Faith was the sustaining hope of those who struggled against totalitarian- ism in the 20th century. It is the basis for a compassionate society. Rather than con- tradicting the sciences, faith is a firm sup- Victor Davis Hanson port on which reason may flourish. 2009 William E. Simon As men and women continue to ask ques- Distinguished Visiting Professor tions about faith and secularism, people in both camps may become more tolerant of Scholar of classical civilizations, author, each other. Novak echoed the prediction columnist, and historian Victor Davis Hanson of the German philosopher Habermas that is serving as the Spring 2009 William E. we are at the “end of the secular age.” Simon Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Now, “believers and unbelievers will have School of Public Policy. He is teaching the to take each other much more seriously seminar in international relations: Global Rule than they did before.” of Western Civilization? In an era when our public discourse Hanson is a Senior Fellow in Residence in “VIRTUALLY ALL THE WORLD seems to lack civility, Novak foresees “the Classics and Military History at the Hoover end of the period of condescension” and Institution at Stanford University and IS IN THE GRIP OF QUESTIONS “the beginning of a conversation that rec- Professor Emeritus of Classics at California ABOUT GOD,”… ognizes each others’ inherent dignity.” State University, Fresno. -

Terrorists, Despots, and Democracy

Terrorists, Despots, and Democracy: What Our Children Need to Know Terrorists, Despots, and Democracy: WHAT OUR CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW August 2003 1 1627 K Street, NW Suite 600 Washington, DC 20006 202-223-5452 www.edexcellence.net THOMAS B. FORDHAM FOUNDATION 2 WHAT OUR CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW CONTENTS WHY THIS REPORT? Introduction by Chester E. Finn, Jr. .5 WHAT CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW ABOUT TERRORISM, DESPOTISM, AND DEMOCRACY . .17 Richard Rodriguez, Walter Russell Mead, Victor Davis Hanson, Kenneth R. Weinstein, Lynne Cheney, Craig Kennedy, Andrew J. Rotherham, Kay Hymowitz, and William Damon HOW TO TEACH ABOUT TERRORISM, DESPOTISM, AND DEMOCRACY . .37 William J. Bennett, Lamar Alexander, Erich Martel, Katherine Kersten, William Galston, Jeffrey Mirel, Mary Beth Klee, Sheldon M. Stern, and Lucien Ellington WHAT TEACHERS NEED TO KNOW ABOUT AMERICA AND THE WORLD . .63 Abraham Lincoln (introduced by Amy Kass), E.D. Hirsch, Jr., John Agresto, Gloria Sesso and John Pyne, James Q. Wilson, Theodore Rabb, Sandra Stotsky and Ellen Shnidman, Mitchell B. Pearlstein, Stephen Schwartz, Stanley Kurtz, and Tony Blair (excerpted from July 18, 2003 address to the U.S. Congress). 3 RECOMMENDED RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS . .98 SELECTED RECENT FORDHAM PUBLICATIONS . .109 THOMAS B. FORDHAM FOUNDATION 4 WHAT OUR CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW WHY THIS REPORT? INTRODUCTION BY CHESTER E. FINN, JR. mericans will debate for many years to come the causes and implications of the September 11 attacks on New York City and Washington, as well as the foiled attack that led to the crash of United Airlines flight 93 in a Pennsylvania field. These assaults comprised far too traumatic an event to set aside immediately like the latest Interstate pile-up. -

With Only a Few Exceptions, the References for the Obama Timeline Are Web Pages

With only a few exceptions, the references for The Obama Timeline are Web pages. Where information was obtained from magazines, books, or newspapers, Web pages were tracked down that contained or confirmed the same information. The result is that anyone with the desire—and the time and the patience—to check the thousands of references can do so without leaving his or her computer. Unlike books, however, Web addresses and Web pages can be changed or deleted over time. It is therefore impossible to expect all the references appearing below to remain permanently accessible. (Obama supporters have also been known to “scrub” the Internet of Web pages that may be considered damaging to him.) In many cases, multiple sources have been listed in order to compensate for the eventual and unpreventable loss of some Web pages. Hopefully, most of the references will remain valid. References 55,001 through 60,000: 55001. http://blogs.denverpost.com/thespot/2014/02/12/colorado-health-care-exchange- montana/105890/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter 55002. http://www.lee.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=96ed4c0a-fe4c-4793- 8060-065f5ca281d5 55003. http://townhall.com/tipsheet/conncarroll/2014/02/12/sen-mike-lee-rut-wants-to-bring- work-back-to-welfare-n1793823 55004. http://www.lee.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/blog?ID=cd1def56-32f1-4d4a-969f- e7c2708795c3 55005. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/13/us/politics/obama-plans-a-royal-weekend-king-or- no-king.html?partner=rss&emc=rss&_r=0 55006. http://hotair.com/archives/2014/02/13/by-the-way-obama-almost-certainly-lied-when- he-said-no-one-told-him-about-healthcare-govs-problems/ 55007. -

The Case of Donald J. Trump†

THE AGE OF THE WINNING EXECUTIVE: THE CASE OF DONALD J. TRUMP† Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash∗ INTRODUCTION The election of Donald J. Trump, although foretold by Matt Groening’s The Simpsons,1 was a surprise to many.2 But the shock, disbelief, and horror were especially acute for the intelligentsia. They were told, guaranteed really, that there was no way for Trump to win. Yet he prevailed, pulling off what poker aficionados might call a back- door draw in the Electoral College. Since his victory, the reverberations, commotions, and uproars have never ended. Some of these were Trump’s own doing and some were hyped-up controversies. We have endured so many bombshells and pur- ported bombshells that most of us are numb. As one crisis or scandal sputters to a pathetic end, the next has already commenced. There has been too much fear, rage, fire, and fury, rendering it impossible for many to make sense of it all. Some Americans sensibly tuned out, missing the breathless nightly reports of how the latest scandal would doom Trump or why his tormentors would soon get their comeuppance. Nonetheless, our reality TV President is ratings gold for our political talk shows. In his Foreword, Professor Michael Klarman, one of America’s fore- most legal historians, speaks of a degrading democracy.3 Many difficulties plague our nation: racial and class divisions, a spiraling debt, runaway entitlements, forever wars, and, of course, the coronavirus. Like many others, I do not regard our democracy as especially debased.4 Or put an- other way, we have long had less than a thoroughgoing democracy, in part ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– † Responding to Michael J. -

Hoover Institution Newsletter Spring 2004

HOOVER INSTITUTION SPRING 2004 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER FEDERAL OFFICIALS, JOURNALISTS, HOOVER FELLOWS HOOVER, SIEPR SHARE DISCUSS DOMESTIC AND WORLD AFFAIRS $5 MILLION GIFT AT BOARD OF OVERSEERS MEETING IN HONOR OF GEORGE P. SHULTZ ecretary of State Colin Powell dis- he Annenberg Foundation has cussed the importance of human granted Stanford University $5 Srights,democracy,and the rule of law Tmillion to honor former U.S. secre- when he addressed the Hoover Institution tary of state George P. Shultz. Board of Overseers and guests on Febru- The Hoover Institution will receive $4 ary 23 in Washington, D.C. million to endow the Walter and Leonore Powell told the group of more than 200 Annenberg Fund in honor of George P. who gathered to hear his postluncheon talk Shultz, which will support the Annenberg that worldwide political and economic Distinguished Visiting Fellow. conditions present not only problems but The Stanford Institute for Economic also great opportunities to share American Policy Research (SIEPR) will receive $1 values. million for the George P. Shultz Disserta- Other speakers during the day included tion Support Fund, which supports empir- Dinesh D’Souza, the Robert and Karen ical research by graduate students working Rishwain Research Fellow, who discussed on dissertations oriented toward problems Colin Powell the future of American conservativism. of economic policy. Reflecting on the legacy of Ronald ing values and virtues that have sustained “In all of his capacities, George has Reagan’s presidency, he pointed to endur- American society for more than 200 years. given unstintingly to this institution over continued on page 8 continued on page 4 PRESIDENT BUSH NAMES HENRY S. -

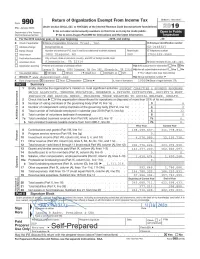

Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check If Schedule O Contains a Response Or Note to Any Line in This Part III

Form 990 (2019) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: SUPPORT CHARITIES & SPONSOR PROGRAMS WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH & PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ........................... Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? ................................. Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization’s program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 163,183,043. including grants of $ 161,930,479. ) (Revenue $0. ) DAF PROGRAM - A DONOR ADVISED FUND (DAF) PROGRAM ALLOWING DAF CONTRIBUTORS TO ADVISE GRANTS THAT SUPPORT CHARITIES WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH AND PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMICS, GOVERNANCE, FOREIGN RELATIONS AND ARTS AND CULTURE; AND WHICH ENCOURAGE PRIVATE PHILANTHROPY AND INDIVIDUAL GIVING AND RESPONSIBILITY AS AN ANSWER TO SOCIETY'S NEEDS, AS OPPOSED TO GOVERNMENTAL INVOLVEMENT. -

Basic Books 3 YORAM HAZONY

BABASICSIC BOOKSBOOKS FALLFALL 20182018 Renowned publisher of serious nonfiction by leading intellectuals, scholars, and journalists new titles fa ll 2018 new hardcovers 3 highlights 38 meet the editors 46 contact information 48 COVER DESIGN BY ANN KIRCHNER PATTERN ILLUSTRATION BY ASHLEY CASWELL ADAM ZAMOYSKI NAPOLEON A Life hat a novel my life has been!” “ Napoleon once said of himself. W Born into a poor family, the callow young man was, by twenty-six, an army general. Seduced by an older woman, his marriage transformed him into a galvanizing military commander. The Pope crowned him as Emperor of the French when he was only thirty-five. Within a few years, he became the effective master of Europe, his power unparalleled in modern history. His downfall was no less dramatic. The story of Napoleon has been written many times. In some versions, he is a military genius, The definitive biography of in others a war-obsessed tyrant. Here, historian Napoleon, revealing the true Adam Zamoyski cuts through the mythology and man behind the legend explains Napoleon against the background of the European Enlightenment, and what he was himself seeking to achieve. This most famous of men is also the most hidden of men, and Zamoyski NEW HARDCOVER • OCTOBER dives deeper than any previous biographer to find Biography / History • $40.00 / $45.00 CAN him. Beautifully written, Napoleon brilliantly sets 6 x 9G • 800 pages the man in his European context. Forty-eight color illustrations and thirty-two maps ADAM ZAMOYSKI is the 978-0-465-05593-7 author of numerous books E-BOOK 978-1-5416-4455-7 about Polish and European Selling Territory: USC history, and has written for publications including the Times (London), the Times Literary Supplement, and the Guardian. -

Mark Steyn, Fred Thompson, John Bolton, Victor Davis Hanson, & Many More Tremendous Speakers (Ok, We’Ll Name Them)

2011_08_01_cover61404-postal.qxd 7/12/2011 8:15 PM Page 1 August 1, 2011 49145 $4.99 MAGGIE GALLAGHER: WHAT’S NEXT FOR MARRIAGE? UnfairUnfair LaborLabor PracticesPractices The Case Against America’s Nightmarish Labor Law $4.99 31 Robert VerBruggen 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/12/2011 11:30 PM Page 1 toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 7/13/2011 1:28 PM Page 2 Contents AUGUST 1, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 14 | www.nationalreview.com COVER STORY Page 31 National Labor Robert Costa on Thaddeus McCotter Relations Bias p. 21 The National Labor Relations Board under Obama has made BOOKS, ARTS few friends among conservatives. & MANNERS But the current behavior of the 40 HOW BIG HE IS David Paul Deavel reviews NLRB is only the outermost layer of G. K. Chesterton: A Biography, the true problem: the National Labor by Ian Ker. Relations Act. Robert VerBruggen 41 ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY? Victor Davis Hanson reviews The Wave: Man, God, and the Ballot COVER: UNDERWOOD & UNDERWOOD/CORBIS Box in the Middle East, by Reuel ARTICLES Marc Gerecht, and Trial of a Thousand Years: World Order 16 ROMNEY’S RESISTIBLE RISE by Ramesh Ponnuru and Islamism, by Charles Hill. The GOP contemplates a wedding of convenience. 43 THE NIEBUHRIAN MEAN 20 REAGAN’S LASTING REALIGNMENT by Michael G. Franc Daniel J. Mahoney reviews Why It shapes politics still. Niebuhr Now?, by John Patrick Diggins. 21 A HARD DAY’S NIGHT by Robert Costa Rep. Thaddeus McCotter wins the insomniac caucus. 45 CHINA’S BIG LIE John Derbyshire reviews Such Is 23 GAY OLD PARTY? by Maggie Gallagher This [email protected], How New York Republicans caved, and where the marriage campaigns go next. -

Colab San Luis Obispo Week of September 23 - 29, 2018

COLAB SAN LUIS OBISPO WEEK OF SEPTEMBER 23 - 29, 2018 THIS WEEK NO BOS MEETING PLANNING COMMISSION BACK IN ACTION SOME INTERESTING DEVELOPMENTS LAST WEEK BACKLOG OF MARIJUANA PERMIT APPS. AND ILLEGAL GROW VIOLATIONS SLOWING OTHER PLANNING DEPARTMENT WORK THE BOARD APPROVED A NEW $730,000 PER YEAR UNIT USE OF CONTRACTOR TO DO IT FASTER AND CHEAPER NOT CONSIDERED BOS ADOPTS PRIVATIZATION OF PUBLIC SAFETY MEDICAL SERVICES PUBLIC FACILITIES FEES REVIEW PERFUNCTORY REVIEW ANESTHETIZES BOS REGIONAL WATER BOARD MEETING ON AG WATER RUNOFF ON SEPT. 20 & 21 LAFCO CANCELLED 1 SLO COLAB IN DEPTH SEE PAGE 11 ARE WE ON THE VERGE OF CIVIL WAR? By VICTOR DAVIS HANSON THE ALINSKY-IZATION OF BRETT KAVANAUGH By Rich Logis THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS No Board of Supervisors Meeting on Tuesday, September 25, 2018 (Not Scheduled) September 25th is a 4th Tuesday, when the Board does not typically meet. San Luis Obispo County Air Pollution Control District APCD Meeting of Wednesday, September 26, 2018 (Scheduled) Item A-8: Request For Proposal For Legal Counsel. Contract District Counsel Ray Biering has announced his retirement. The SLOCOG Board will be considering the content of Request for Proposals (RFP) for a new attorney. He will also be retiring from the SLO County Solid Waste Authority, where there is an unraveling scandal over allegations of fraud, misuse of public funds, and cronyism. He is also apparently retiring as LAFCO’s contract attorney. LAFCO has issued a request for proposals for a new contract attorney. It is not known if his sudden retirement is related to the mess at the Waste Authority or not. -

Review of Victor Davis Hanson, the Other Greeks: the Family Farm and the Agrarian Roots of Western Civilization

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of February 1996 Review of Victor Davis Hanson, The Other Greeks: The Family Farm and the Agrarian Roots of Western Civilization Vanessa B. Gorman University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Part of the History Commons Gorman, Vanessa B., "Review of Victor Davis Hanson, The Other Greeks: The Family Farm and the Agrarian Roots of Western Civilization" (1996). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 96.02.11 Victor Davis Hanson, The Other Greeks: The Family Farm and the Agrarian Roots of Western Civilization. New York: The Free Press, 1995. Pp. xvi + 541. $28.00. ISBN 0- 02-913751-9. Reviewed by Vanessa B. Gorman, History -- University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] The Other Greeks, is a challenge to the typical scholarly approach to the rise and fall of the Greek polis. Hanson's central thesis is that the agrarian culture of Greece from the seventh to the fourth century BC is completely responsible for the political, economic, and social systems of that era. In particular, economic development and social stability resulted from the Greek recognition of the importance of the private ownership of land, the need to address the inequalities that arose from agrarianism, and the need to construct rules limiting the cost and destruction of war (pp. -

California Feudalism 3 Authors

CENTER FOR DEMOGRAPHICS & POLICY RESEARCH BRIEF CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR DEMOGRAPHICS & POLICY RESEARCH BRIEF CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR DEMOGRAPHICS & POLICY RESEARCH BRIEF CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY by Joel Kotkin and Marshall Toplansky 2018 CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY PRESS CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY PRESS CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY PRESS CENTER FOR DEMOGRAPHICS & POLICY RESEARCH BRIEF CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR DEMOGRAPHICS & POLICY RESEARCH BRIEF CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR DEMOGRAPHICS & POLICY RESEARCH BRIEF CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY “Demographics is destiny” has become somewhat an overused phrase, but that does not reduce the critical importance of population trends to virtually every aspect of economic, social and political life. Concern over demographic trends has been heightened in recent years by several international trends — notably rapid aging, reduced fertility, large scale migration across borders. On the national level, shifts in attitude, gener- ation and ethnicity have proven decisive in both the political realm and in the economic fortunes of regions and states. The Center focuses research and analysis of global, national and regional demographic trends and also looks into poli- cies that might produce favorable demographic results over time. In addition it involves Chapman students in demo- graphic research under the supervision of the Center’s senior staff. Students work with the Center’s director and engage in research that will serve them well as they look to develop their careers in business, the social sciences and the arts. They will also have access to our advisory board, which includes distin- guished Chapman faculty and major demographic scholars from across the country and the world. 2 CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY • CENTER FOR DEMOGRAPHICS AND POLICY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH CENTERS: The Earl Babbie Research Center is dedicated to empowering students and faculty to apply a wide variety of qualitative and quantitative social research methods to conduct studies that address critical social, behavioral, economic and environmental problems.