My Father, Shall I Kill Them?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union County

• News • Arts • Entertainment • Classified • Real Estate Union County • Automotive WORRALL COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS THURSDAY, MAY 11,2000 • SECTION B http://www.toca!«ouic&c«ii In their Assembly bill would Comparison of county tax levy, 1997-2000 , m' im IKS Cbmge Berkeley Heights $7,094,341 $7,913,617 18,370,956 $8,551,164 +S180.2O6 own right alter freeholder seats Clark SS,601,807 $5,363,129 $6,139,768 $5,332,667 •$192,899 Cranford S9,026,277 +S123.670 Georg's W. Bush anil Al Gore S9,306,«94 16,904,847 $8,904,607 By Mark Hrywna Gsiwood have one'thing in common. Aftei SI ,377,234 $1,399,666 $1,340,745 tl.346,430 +S7.685 Regional Editor Elizabeth -S370.101 some detours.they both ended up in $15,443,145 $14,674,095 ' $16,041,242 $14,671,141 - Republicans call it betler represen- Fanwood 52,343,375 the some professional field as their $2,423,075 $2,362,294 $2,408,778 •S26.484 tation of the people, bringing govern- ' Hillskle $4,327,759 $4,387,693 •SS.881 famous fathers. S4,4S0,S91 $4,382,012 mem closer to constituents, Demo- • Kenilworth $3,820,427 $3,668,079 $3,722,306 $3,750,619 +$28,313 Following in the footsteps of crats say the GOP is simply trying to Linden $12,343,861 $12,949,977 $13,018,563 $11,455,594 •S1.SS2.9S9 your parent is not that uncommon. overcome Us fuiilliy in recent elec- Mountainside $3,849,955 $4,120,739 $4,114,451 $4,172,760 +$58,309 • Bui for those making the second set tion!: by legislating a teat on the free- New Providence SS.031,291 $6,002,681 (6,091.012 $6,178,234 +S87.222 of prints the experience can be full holder board. -

Winter 2009 Licata Lecture: Michael Novak Calls for Conversation About God

WINTER 2009 LICATA LECTURE: MICHAEL NOVAK CALLS FOR CONVERSATION ABOUT GOD And yet, he told his Pepperdine audi- ence faith is a “real knowledge—a practi- cal kind of knowledge worth trusting one’s life to.” Faith was the sustaining hope of those who struggled against totalitarian- ism in the 20th century. It is the basis for a compassionate society. Rather than con- tradicting the sciences, faith is a firm sup- Victor Davis Hanson port on which reason may flourish. 2009 William E. Simon As men and women continue to ask ques- Distinguished Visiting Professor tions about faith and secularism, people in both camps may become more tolerant of Scholar of classical civilizations, author, each other. Novak echoed the prediction columnist, and historian Victor Davis Hanson of the German philosopher Habermas that is serving as the Spring 2009 William E. we are at the “end of the secular age.” Simon Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Now, “believers and unbelievers will have School of Public Policy. He is teaching the to take each other much more seriously seminar in international relations: Global Rule than they did before.” of Western Civilization? In an era when our public discourse Hanson is a Senior Fellow in Residence in “VIRTUALLY ALL THE WORLD seems to lack civility, Novak foresees “the Classics and Military History at the Hoover end of the period of condescension” and Institution at Stanford University and IS IN THE GRIP OF QUESTIONS “the beginning of a conversation that rec- Professor Emeritus of Classics at California ABOUT GOD,”… ognizes each others’ inherent dignity.” State University, Fresno. -

Terrorists, Despots, and Democracy

Terrorists, Despots, and Democracy: What Our Children Need to Know Terrorists, Despots, and Democracy: WHAT OUR CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW August 2003 1 1627 K Street, NW Suite 600 Washington, DC 20006 202-223-5452 www.edexcellence.net THOMAS B. FORDHAM FOUNDATION 2 WHAT OUR CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW CONTENTS WHY THIS REPORT? Introduction by Chester E. Finn, Jr. .5 WHAT CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW ABOUT TERRORISM, DESPOTISM, AND DEMOCRACY . .17 Richard Rodriguez, Walter Russell Mead, Victor Davis Hanson, Kenneth R. Weinstein, Lynne Cheney, Craig Kennedy, Andrew J. Rotherham, Kay Hymowitz, and William Damon HOW TO TEACH ABOUT TERRORISM, DESPOTISM, AND DEMOCRACY . .37 William J. Bennett, Lamar Alexander, Erich Martel, Katherine Kersten, William Galston, Jeffrey Mirel, Mary Beth Klee, Sheldon M. Stern, and Lucien Ellington WHAT TEACHERS NEED TO KNOW ABOUT AMERICA AND THE WORLD . .63 Abraham Lincoln (introduced by Amy Kass), E.D. Hirsch, Jr., John Agresto, Gloria Sesso and John Pyne, James Q. Wilson, Theodore Rabb, Sandra Stotsky and Ellen Shnidman, Mitchell B. Pearlstein, Stephen Schwartz, Stanley Kurtz, and Tony Blair (excerpted from July 18, 2003 address to the U.S. Congress). 3 RECOMMENDED RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS . .98 SELECTED RECENT FORDHAM PUBLICATIONS . .109 THOMAS B. FORDHAM FOUNDATION 4 WHAT OUR CHILDREN NEED TO KNOW WHY THIS REPORT? INTRODUCTION BY CHESTER E. FINN, JR. mericans will debate for many years to come the causes and implications of the September 11 attacks on New York City and Washington, as well as the foiled attack that led to the crash of United Airlines flight 93 in a Pennsylvania field. These assaults comprised far too traumatic an event to set aside immediately like the latest Interstate pile-up. -

With Only a Few Exceptions, the References for the Obama Timeline Are Web Pages

With only a few exceptions, the references for The Obama Timeline are Web pages. Where information was obtained from magazines, books, or newspapers, Web pages were tracked down that contained or confirmed the same information. The result is that anyone with the desire—and the time and the patience—to check the thousands of references can do so without leaving his or her computer. Unlike books, however, Web addresses and Web pages can be changed or deleted over time. It is therefore impossible to expect all the references appearing below to remain permanently accessible. (Obama supporters have also been known to “scrub” the Internet of Web pages that may be considered damaging to him.) In many cases, multiple sources have been listed in order to compensate for the eventual and unpreventable loss of some Web pages. Hopefully, most of the references will remain valid. References 55,001 through 60,000: 55001. http://blogs.denverpost.com/thespot/2014/02/12/colorado-health-care-exchange- montana/105890/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter 55002. http://www.lee.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=96ed4c0a-fe4c-4793- 8060-065f5ca281d5 55003. http://townhall.com/tipsheet/conncarroll/2014/02/12/sen-mike-lee-rut-wants-to-bring- work-back-to-welfare-n1793823 55004. http://www.lee.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/blog?ID=cd1def56-32f1-4d4a-969f- e7c2708795c3 55005. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/13/us/politics/obama-plans-a-royal-weekend-king-or- no-king.html?partner=rss&emc=rss&_r=0 55006. http://hotair.com/archives/2014/02/13/by-the-way-obama-almost-certainly-lied-when- he-said-no-one-told-him-about-healthcare-govs-problems/ 55007. -

The Case of Donald J. Trump†

THE AGE OF THE WINNING EXECUTIVE: THE CASE OF DONALD J. TRUMP† Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash∗ INTRODUCTION The election of Donald J. Trump, although foretold by Matt Groening’s The Simpsons,1 was a surprise to many.2 But the shock, disbelief, and horror were especially acute for the intelligentsia. They were told, guaranteed really, that there was no way for Trump to win. Yet he prevailed, pulling off what poker aficionados might call a back- door draw in the Electoral College. Since his victory, the reverberations, commotions, and uproars have never ended. Some of these were Trump’s own doing and some were hyped-up controversies. We have endured so many bombshells and pur- ported bombshells that most of us are numb. As one crisis or scandal sputters to a pathetic end, the next has already commenced. There has been too much fear, rage, fire, and fury, rendering it impossible for many to make sense of it all. Some Americans sensibly tuned out, missing the breathless nightly reports of how the latest scandal would doom Trump or why his tormentors would soon get their comeuppance. Nonetheless, our reality TV President is ratings gold for our political talk shows. In his Foreword, Professor Michael Klarman, one of America’s fore- most legal historians, speaks of a degrading democracy.3 Many difficulties plague our nation: racial and class divisions, a spiraling debt, runaway entitlements, forever wars, and, of course, the coronavirus. Like many others, I do not regard our democracy as especially debased.4 Or put an- other way, we have long had less than a thoroughgoing democracy, in part ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– † Responding to Michael J. -

Combatant Status and Computer Network Attack

Combatant Status and Computer Network Attack * SEAN WATTS Introduction .......................................................................................... 392 I. State Capacity for Computer Network Attacks ......................... 397 A. Anatomy of a Computer Network Attack ....................... 399 1. CNA Intelligence Operations ............................... 399 2. CNA Acquisition and Weapon Design ................. 401 3. CNA Execution .................................................... 403 B. State Computer Network Attack Capabilites and Staffing ............................................................................ 405 C. United States’ Government Organization for Computer Network Attack .............................................. 407 II. The Geneva Tradition and Combatant Immunity ...................... 411 A. The “Current” Legal Framework..................................... 412 1. Civilian Status ...................................................... 414 2. Combatant Status .................................................. 415 3. Legal Implications of Status ................................. 420 B. Existing Legal Assessments and Scholarship.................. 424 C. Implications for Existing Computer Network Attack Organization .................................................................... 427 III. Departing from the Geneva Combatant Status Regime ............ 430 A. Interpretive Considerations ............................................. 431 * Assistant Professor, Creighton University Law School; Professor, -

Hoover Institution Newsletter Spring 2004

HOOVER INSTITUTION SPRING 2004 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER FEDERAL OFFICIALS, JOURNALISTS, HOOVER FELLOWS HOOVER, SIEPR SHARE DISCUSS DOMESTIC AND WORLD AFFAIRS $5 MILLION GIFT AT BOARD OF OVERSEERS MEETING IN HONOR OF GEORGE P. SHULTZ ecretary of State Colin Powell dis- he Annenberg Foundation has cussed the importance of human granted Stanford University $5 Srights,democracy,and the rule of law Tmillion to honor former U.S. secre- when he addressed the Hoover Institution tary of state George P. Shultz. Board of Overseers and guests on Febru- The Hoover Institution will receive $4 ary 23 in Washington, D.C. million to endow the Walter and Leonore Powell told the group of more than 200 Annenberg Fund in honor of George P. who gathered to hear his postluncheon talk Shultz, which will support the Annenberg that worldwide political and economic Distinguished Visiting Fellow. conditions present not only problems but The Stanford Institute for Economic also great opportunities to share American Policy Research (SIEPR) will receive $1 values. million for the George P. Shultz Disserta- Other speakers during the day included tion Support Fund, which supports empir- Dinesh D’Souza, the Robert and Karen ical research by graduate students working Rishwain Research Fellow, who discussed on dissertations oriented toward problems Colin Powell the future of American conservativism. of economic policy. Reflecting on the legacy of Ronald ing values and virtues that have sustained “In all of his capacities, George has Reagan’s presidency, he pointed to endur- American society for more than 200 years. given unstintingly to this institution over continued on page 8 continued on page 4 PRESIDENT BUSH NAMES HENRY S. -

Noncombatant Immunity and War-Profiteering

In Oxford Handbook of Ethics of War / Published 2017 / doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199943418.001.0001 Noncombatant Immunity and War-Profiteering Saba Bazargan Department of Philosophy UC San Diego Abstract The principle of noncombatant immunity prohibits warring parties from intentionally targeting noncombatants. I explicate the moral version of this view and its criticisms by reductive individualists; they argue that certain civilians on the unjust side are morally liable to be lethally targeted to forestall substantial contributions to that war. I then argue that reductivists are mistaken in thinking that causally contributing to an unjust war is a necessary condition for moral liability. Certain noncontributing civilians—notably, war-profiteers— can be morally liable to be lethally targeted. Thus, the principle of noncombatant immunity is mistaken as a moral (though not necessarily as a legal) doctrine, not just because some civilians contribute substantially, but because some unjustly enriched civilians culpably fail to discharge their restitutionary duties to those whose victimization made the unjust enrichment possible. Consequently, the moral criterion for lethal liability in war is even broader than reductive individualists have argued. 1 In Oxford Handbook of Ethics of War / Published 2017 / doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199943418.001.0001 1. Background 1.1. Noncombatant Immunity and the Combatant’s Privilege in International Law In Article 155 of what came to be known as the ‘Lieber Code’, written in 1866, Francis Lieber wrote ‘[a]ll enemies in regular war are divided into two general classes—that is to say, into combatants and noncombatants’. As a legal matter, this distinction does not map perfectly onto the distinction between members and nonmembers of an armed force. -

Fm 6-27 Mctp 11-10C the Commander's Handbook on the Law of Land Warfare

FM 6-27 MCTP 11-10C THE COMMANDER'S HANDBOOK ON THE LAW OF LAND WARFARE AUGUST 2019 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes FM 27-10/MCTP 11-10C, dated 18 July 1956. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY HEADQUARTERS, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS Foreword The lessons of protracted conflict confirm that adherence to the law of armed conflict (LOAC) by the land forces, both in intern ational and non-international armed conflict, must serve as the standard that we train to and apply across the entire range of military operations. Adhering to LOAC enhances the legitimacy of our operations and supports the moral framework of our armed forces. We have learned th at we deviate from these norms to our detriment and risk undercutting both domesti c and international support for our operations. LOAC has been and remains a vital guide for all military operations conducted by the U.S. Governm ent. This fi eld manual provides a general description of the law of land warfare for Soldiers and Marines, delineated as statements of doctrine and practice, to gui de the land forces in conducting di sci plined military operations in accordance with the rule of law. The Department of Defense Law of War Manual (June 20 15, updated December 2016) is the authoritative statement on the law of war for the Department of Defense. In the event of a conflict or discrepancy regarding the legal standards addressed in this publication and th e DOD Law of War Manual, the latter takes precedence. -

Al-Qaeda & Taliban Unlawful Combatant

AL-QAEDA & TALIBAN UNLAWFUL COMBATANT DETAINEES,..., 55 A.F. L. Rev. 1 55 A.F. L. Rev. 1 Air Force Law Review 2004 Article AL-QAEDA & TALIBAN UNLAWFUL COMBATANT DETAINEES, UNLAWFUL BELLIGERENCY, AND THE INTERNATIONAL LAWS OF ARMED CONFLICT Lieutenant Colonel (s) Joseph P. “Dutch” Bialkea1 Copyright © 2004 by Lieutenant Colonel (s) Joseph P. “Dutch” Bialke I. INTRODUCTION International Obligations & Responsibilities and the International Rule of Law The United States (U.S.) is currently detaining several hundred al-Qaeda and Taliban unlawful enemy combatants from more than 40 countries at a multi-million dollar maximum-security detention facility at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. These enemy detainees were captured while engaged in hostilities against the U.S. and its allies during the post-September 11, 2001 international armed conflict centered primarily in Afghanistan. The conflict now involves an ongoing concerted international campaign in collective self-defense against a common stateless enemy dispersed throughout the world. Domestic and international human rights organizations and other groups have criticized the U.S.,1 arguing that al-Qaeda and Taliban detainees in Cuba should be granted Geneva Convention III prisoner of war (POW)2status. They contend broadly that pursuant to the international laws of armed conflict (LOAC), combatants captured during armed conflict must be treated equally and conferred POWstatus. However, no such blanket obligation exists in international law. There is no legal or moral equivalence in LOAC between lawful combatants and unlawful combatants, or between lawful belligerency *2 and unlawful belligerency (also referred to as lawful combatantry and unlawful combatantry). -

INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Answers to Your Questions 2

INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Answers to your Questions 2 THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS (ICRC) Founded by five Swiss citizens in 1863 (Henry Dunant, Basis for ICRC action Guillaume-Henri Dufour, Gustave Moynier, Louis Appia and Théodore Maunoir), the ICRC is the founding member of the During international armed conflicts, the ICRC bases its work on International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Additional Protocol I of 1977 (see Q4). Those treaties lay down the ICRC’s right to • It is an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian institution. carry out certain activities such as bringing relief to wounded, • It was born of war over 130 years ago. sick or shipwrecked military personnel, visiting prisoners of war, • It is an organization like no other. aiding civilians and, in general terms, ensuring that those • Its mandate was handed down by the international community. protected by humanitarian law are treated accordingly. • It acts as a neutral intermediary between belligerents. • As the promoter and guardian of international humanitarian law, During non-international armed conflicts, the ICRC bases its work it strives to protect and assist the victims of armed conflicts, on Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions and internal disturbances and other situations of internal violence. Additional Protocol II (see Index). Article 3 also recognizes the ICRC’s right to offer its services to the warring parties with a view The ICRC is active in about 80 countries and has some 11,000 to engaging in relief action and visiting people detained in staff members (2003). -

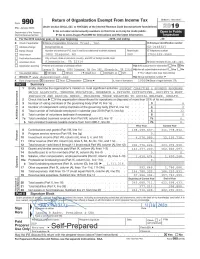

Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check If Schedule O Contains a Response Or Note to Any Line in This Part III

Form 990 (2019) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: SUPPORT CHARITIES & SPONSOR PROGRAMS WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH & PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ........................... Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? ................................. Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization’s program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 163,183,043. including grants of $ 161,930,479. ) (Revenue $0. ) DAF PROGRAM - A DONOR ADVISED FUND (DAF) PROGRAM ALLOWING DAF CONTRIBUTORS TO ADVISE GRANTS THAT SUPPORT CHARITIES WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH AND PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMICS, GOVERNANCE, FOREIGN RELATIONS AND ARTS AND CULTURE; AND WHICH ENCOURAGE PRIVATE PHILANTHROPY AND INDIVIDUAL GIVING AND RESPONSIBILITY AS AN ANSWER TO SOCIETY'S NEEDS, AS OPPOSED TO GOVERNMENTAL INVOLVEMENT.