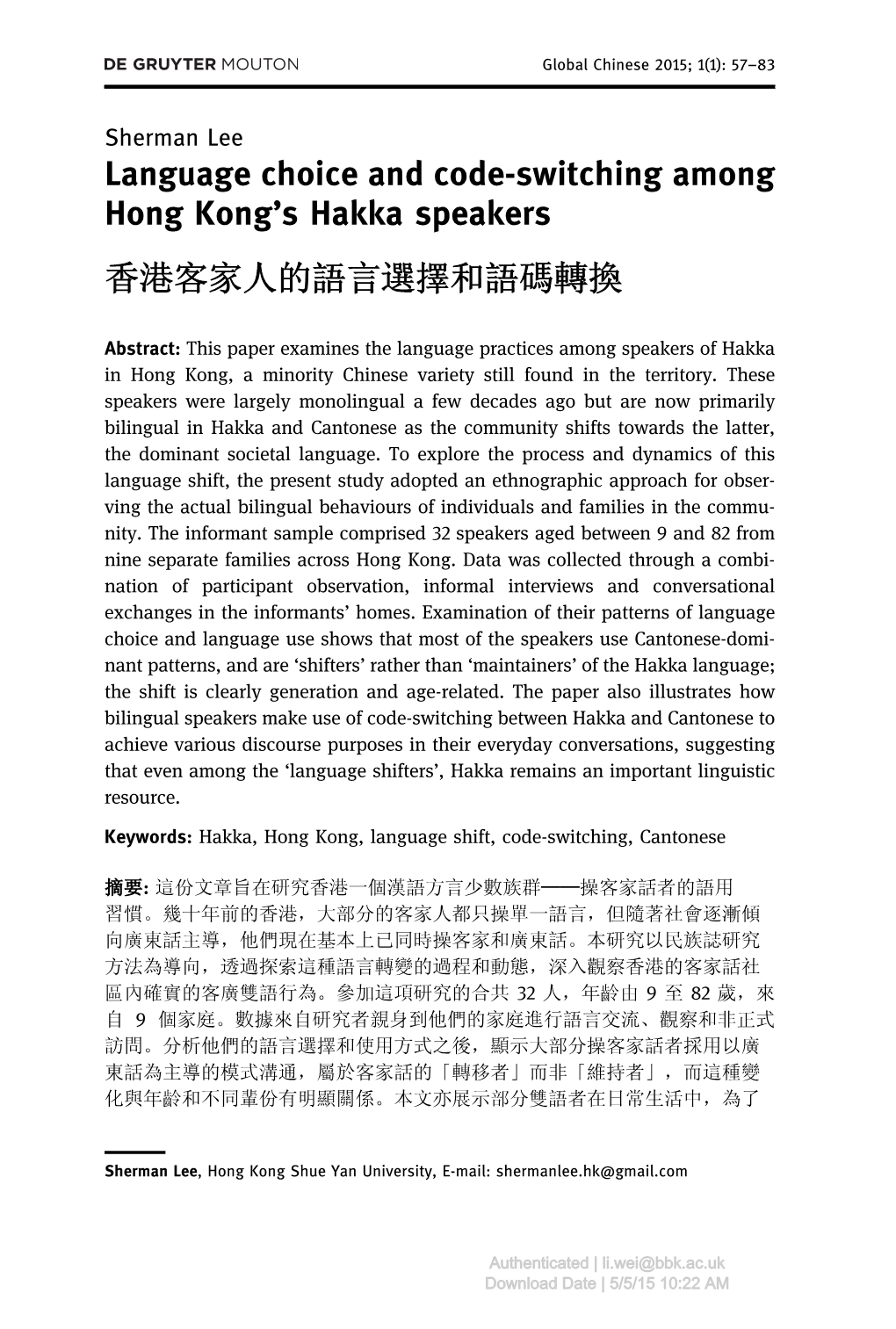

Language Choice and Code-Switching Among Hong Kong's Hakka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hansard (English)

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 20 October 2010 241 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 20 October 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. 242 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 20 October 2010 THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. -

Hon. Wayne Yiu Si-Wing Working Report 2012 - 2013

Hon. Wayne Yiu Si-Wing Working Report 2012 - 2013 Foreword Dear friends and fellow colleagues, stamp duty collected from With much sincerity, let me thank you all for outbound tours increased your long-term and unfailing support. As the LegCo by 5.4%, the Hong Kong session 2012-13 has come to an end, I would like International Airport marked to review the work I have done in the past year and new records in both passenger present my report. Through sharing the achievements capacity and flight frequency by of my efforts, let us mutually encourage each other attaining annual growth of 4.7% and perform even better as we look into the future. and 5.3% respectively, and the annual average hotel occupancy It is an indisputable fact that the nearly 1,700 rate was up to 89%. All such travel agencies compete fiercely and can barely survive by achievements have indicated that there is still much room for making minimal profits. In addition, the turning of product tourism to develop. suppliers to direct sales, along with increasing costs in manpower and rental costs, have made operation within the To solve the aforementioned hurdles, our fellow members tourism industry even more difficult. The lack of government need to unite, build consensus, and urge the government to plans for the industry of Hong Kong over the years has given take measures for practical solutions. As the representative of inadequate support for tourist attractions, hotels, parking tourism in Hong Kong, I hold the duty to safeguard the rights and other facilities, whereas the confusing immigration and interests of our industry; as the communication channel, clearance arrangements also impacted much on the travelers’ I speak in the LegCo on behalf of our fellow members. -

Shenzhen-Hong Kong Borderland

FORUM Transformation of Shen Kong Borderlands Edited by Mary Ann O’DONNELL Jonathan BACH Denise Y. HO Hong Kong view from Ma Tso Lung. PC: Johnsl. Transformation of Shen Kong Borderlands Mary Ann O’DONNELL Jonathan BACH Denise Y. HO n August 1980, the Shenzhen Special and transform everyday life. In political Economic Zone (SEZ) was formally documents, newspaper articles, and the Iestablished, along with SEZs in Zhuhai, names of businesses, Shenzhen–Hong Kong is Shantou, and Xiamen. China’s fifth SEZ, Hainan shortened to ‘Shen Kong’ (深港), suturing the Island, was designated in 1988. Yet, in 2020, cities together as specific, yet diverse, socio- the only SEZ to receive national attention on technical formations built on complex legacies its fortieth anniversary was Shenzhen. Indeed, of colonial occupation and Cold War flare-ups, General Secretary Xi Jinping attended the checkpoints and boundaries, quasi-legal business celebration, reminding the city, the country, opportunities, and cross-border peregrinations. and the world not only of Shenzhen’s pioneering The following essays show how, set against its contributions to building Socialism with Chinese changing cultural meanings and sifting of social Characteristics, but also that the ‘construction orders, the border is continuously redeployed of the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Greater and exported as a mobile imaginary while it is Bay Area is a major national development experienced as an everyday materiality. Taken strategy, and Shenzhen is an important engine together, the articles compel us to consider how for the construction of the Greater Bay Area’ (Xi borders and border protocols have been critical 2020). Against this larger background, many to Shenzhen’s success over the past four decades. -

Black-Faced Spoonbill, Spoon-Billed Sandpiper and Chinese Crested Tern

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals Secretariat provided by the United Nations Environment Programme 14 th MEETING OF THE CMS SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bonn, Germany, 14-17 March 2007 CMS/ScC14/Doc.16 Agenda item 5.1 PROGRESS REPORT ON THE INTERNATIONAL ACTION PLANS FOR THE CONSERVATION OF THE BLACK-FACED SPOONBILL ( PLATALEA MINOR ), SPOON-BILLED SANDPIPER ( EURYNORHYNCHUS PYGMEUS ), AND CHINESE CRESTED-TERN ( STERNA BERNSTEINI ) (Prepared by Mr. Simba Chan, BirdLife International Asia Division) I. Progress to March 2007 1. Preparation of the International Action Plans (IAP) for Black-faced Spoonbill, Chinese Crested-tern and Spoon-billed Sandpiper was unofficially started in late 2004, when BirdLife International Asia Division contacted experts on these species for their involvement in drafting the IAPs. As BirdLife International and its partners in Asia have been involved in conservation activities of Black-faced Spoonbill and Chinese Crested-tern, we believe it is best to have these two species IAP coordinated under BirdLife International Asia Division. On the IAP for Spoon- billed Sandpiper, BirdLife International approached the Shorebird Network of the Asia- Australasian Flyway for cooperation. They recommended Dr Christoph Zöckler, a Spoon-billed Sandpiper expert, to be the coordinator. BirdLife International had discussed with Dr Zöckler several times since 2004 and finally signed an agreement regarding the IAP after signing the Letter of Agreement with the CMS in early 2006. Black-faced Spoonbill Platalea minor 2. Drafting of the IAP for Black-faced Spoonbill goes on smoothly, with four working meetings between compilers who represent all major range countries (Japan, North Korea, South Korea, China including the island of Taiwan and the Hong Kong Special Administration Region) and workshop and symposia held in Tokyo, Tainan (Taiwan), Hong Kong and Ganghwa (South Korea): Tokyo, Japan : 2-6 October 2005 Meeting during the BirdLife Asia Council Meeting and a workshop at the Korea University, Tokyo. -

場刊house Programme

場 刊 House Programme 節目簡介 忘記了 卻不想忘記 那天一覺醒來 一切都去了 倒下來 還是要繼續 高掛高掛高高掛 前進前進前前進 我們其實都很幸福 誰與誰在誰左誰右誰上誰下誰前誰後胡說八道 高舉著掉下來 再高高舉在上 再狠狠地掉下來 迷了 著了迷 被迷着了 在自由的空氣中窒息地呼吸 在框架中閒人在跳舞 被帶到遙遠的國度去 1 節目簡介 我的爺爺是屠夫 在歌唱尖叫狂奔 在希望的門前門後進進出出 出門入門開門關門閂門 人們你們我們 記起來 還是記不起 生下來 還是被生生的生下 門卻仍然關上 還有她他牠的媽的他媽的媽媽 門開了沒有? 完了還是沒完沒了...... 2 「多空間」 「多空間」於1995年3月由馬才和及嚴明然於香港成立,是一個非牟利的表演 藝術團體。成立宗旨是希望透過舞蹈來開拓表演藝術的可能性、尋找新的舞蹈 語言及演出路向。其作品除糅合不同媒體作創作元素外,更嘗試打破形式的規 限,於劇場內外各種不同空間進行創作及表演,當中包括:即興創作、舞蹈劇 場、環境舞蹈、純舞蹈表演,以至舞蹈影帶製作等。 「多空間」成立至今,其作品曾多次被國際藝術節及藝術機構邀請前往參與表 演及交流。更不斷積極在本地民間推廣舞蹈藝術及透過「Y劇場」開拓另類的 創作和欣賞空間。而多年來,「多空間」除致力將其藝團發展成為一個富本土 文化特色的表演團體外,更積極參與國際間的文化交流活動。 Y-Space Y-Space was founded in 1995 by Victor Choi-wo Ma and Mandy Ming-yin Yim in Hong Kong, with the mission of exploring the infinite possibilities of dance, and searching for new dance idioms and new artistic directions. Y-Space has been invited by international arts festivals and arts organizations to perform and conduct artistic exchange. To date, its Improvisation Land series has reached its 42nd series, while its Dancing All Around series has gone beyond the 10th mark. Since 2009, Y-Space has been hosting the i-Dance HK festival. Now in its 18th year, Y-Space has become an important arts group on the Hong Kong contemporary dance through creating new work, promoting dance and providing training, education and research work through activities conducted at community level and at the Y-Space Dance Studio. 3 導演的話 寫在《門》邊上 田戈兵 2014年的《鐵馬》之後,香港似乎漸行漸遠。 去年在北京遇見馬才和嚴明然夫婦,馬試探我:「願不願在他來年新作 裏做劇場構作?」我很快答應,雖然有這樣那樣的時間問題,但我好奇 這個「不靠譜」的想法。當然,還有一個原因就是想看看四年以後的香 港現況。 -

Technical Tour 1

TECHNICAL TOUR 1 19July 2009 (Sunday) Lok Ma Chau Spur Line The Sheung Shui to Lok Ma Chau (LMC) Spur Line was commissioned on 15 August 2007. The 7.4 km long LMC Spur Line is the second cross-boundary railway between Hong Kong and Shenzhen. It helps to relieve the congestion at other land boundary crossings and cater for the increasing cross-boundary traffic demand. The journey time for the spur line running from the existing East Rail Line from Sheung Shui Station to LMC Station is about six minutes. Passengers of the Spur Line alighting at the LMC Terminus can walk towards the Futian Port through a passenger bridge across the Shenzhen River and, after clearing immigration and custom control, take the Shenzhen Metro Line 4 at the Huangang Station at the basement of the Futian Port. The boundary crossing in the Lok Ma Chau Terminus Building will be able to handle up to 150,000 passengers a day. Passenger Bridge, across the Shenzhen River, linking up the LMC Terminus (on the left) to the Futian Port Building (on the right). 2 Quota: Limited (First-come first-served) To visit LMC spur line which is Frontier Closed Area, all visitors must hold Closed Area Permit from The Hong Kong Police Force. Please submit completed registration form of technical visit (downloadable from the symposium website: www.isttt18.org) to [email protected] by 8 July 2009. The organizers will apply Closed Area Permit for all visitors. Visitors without the Closed Area Permit are not allowed to visit LMC spur line. -

Hong Kong's Border Regime and Its Role in National Sovereignty Aaron Mok [email protected]

Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity Volume 5 Article 12 Issue 1 Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal 4-11-2019 Hong Kong's Border Regime and its Role in National Sovereignty Aaron Mok [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/alpenglowjournal Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Mok, A. (2019). Hong Kong's Border Regime and its Role in National Sovereignty. Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity, 5(1). Retrieved from https://orb.binghamton.edu/alpenglowjournal/vol5/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Hong Kong’s “One Country, Two Systems” government regime will end by 2047and it will promote the country’s integration into the People’s Republic of China (PRC). To ensure a smooth transition, by eliminating the border and other forms of geographic barriers that separate the two countries, the PRC has been issuing measures to promote integration. However, despite on-going practices of integration, Hong Kong continues to strengthen its border with China through infrastructural and bureaucratic means, reinforcing a British-colonial era border regime. Thus, my research focuses on this contradiction between the elimination and reinforcement of the Hong Kong-China border as an attempt to understand the socio-political forces that have produced this dynamic. -

The Future of Frontier Closed Area By

THE FUTURE OF FRONTIER CLOSED AREA BY CHAN PAT FAN Student No.: 01014641 AN HONOURS PROJECT SUBMITTEDIN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SOCIAL SCIENCES (HONOURS) IN GEOGRAPHY HONG KONG BAPTIST UNIVERSITY 04/2004 HONG KONG BAPTIST UNIVERSITY April / 2004 We hereby recommend that the Honours Project by Mr. CHAN Pat Fan, entitled “The Future of Frontier Closed Area” be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Social Sciences (Honours) in Geography. _________________ _________________ Professor S. M. Li Dr. C. S. Chow Chief Adviser Second Examiner Continuous Assessment: _______________ Product Grade: _______________________ Overall Grade: _______________________ 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor S. M. LI for suggesting the research topic and guiding me through the entire study. In addition, also thank for staff of The Public Records Office of Hong Kong (PRO) provide me useful information and documentaries. _____________________ Student’s signature Department of Geography Hong Kong Baptist University Date: 5th April 2004 ___ 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS ---------------------------------------------------------------------I LIST OF TABLES ------------------------------------------------------------------II LIST OF PLATES ------------------------------------------------------------------III ABSTRACT--------------------------------------------------------------------------IV CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGORUND OF FRONTIER -

Legislative Council Panel on Security Policy on Frontier Closed Area

LC Paper No. CB(2)1713/01-02(06) Legislative Council Panel on Security Policy on Frontier Closed Area Purpose This paper briefs Members on the Government’s policy on the Frontier Closed Area (FCA), how the coverage of FCA was delineated, the reasons for the retention of the policy on FCA and its coverage. The FCA Policy 2. In view of the considerable border activities and the increasing number of illegal immigrants from the Mainland after the Second World War, the Government introduced the FCA policy in 1951 Under the FCA policy, certain area between the populated territory of Hong Kong and the then Sino- British border was declared to be the FCA to provide a buffer zone to help the security forces to maintain the integrity of the boundary between Hong Kong and the Mainland and to combat illegal immigration and other cross boundary criminal activities. Access to the FCA was controlled by the Police through the issue of the FCA Permits based on need. Coverage of the FCA 3. FCA was first statutorily defined in June 1951 by way of a Government Gazette Notice. The FCA was extended to its present boundary in May 1962. The total area of the FCA is about 28 sq. kilometres which covers North District and northeast part of Yuen Long. The northern boundary of the FCA runs along the 35km-long land boundary between HKSAR and the Mainland and is demarcated by a perimeter fence and a boundary road. The southern boundary of the FCA runs roughly parallel to the land boundary and includes all the waters of Starling Inlet. -

Paper on Review of the Frontier Closed Area Prepared by The

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1060/07-08(03) Ref : CB2/PL/SE Panel on Security Background brief prepared by the Legislative Council Secretariat for the meeting on 19 February 2008 Frontier Closed Area Purpose This paper summarises the past discussions held by Members since the First Legislative Council (LegCo) on the Frontier Closed Area (FCA). The FCA Policy 2. In view of the considerable border activities and the increasing number of illegal immigrants from the Mainland after the Second World War, the Government introduced the FCA policy in 1951. Under the FCA policy, certain areas between the populated territory of Hong Kong and the then Sino-British border was declared to be the FCA to provide a buffer zone to help the security forces to maintain the integrity of the boundary between Hong Kong and the Mainland and to combat illegal immigration and other cross boundary criminal activities. 3. The FCA was first defined statutorily in June 1951 by way of a Government Gazette Notice. The FCA was extended to its present boundary in May 1962, with a total area of about 2 800 hectares of land which covers North District and the northeast part of Yuen Long. The northern boundary of the FCA runs along the 35km-long land boundary between the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) and the Mainland, and is demarcated by a perimeter fence and a boundary road. The southern boundary of the FCA runs roughly parallel to the land boundary and includes all the waters of Starling Inlet. The current delineation of the southern boundary of the FCA has been determined to a large extent by reference to the topography, road and infrastructure network and access to Police support facilities. -

Hansard and Minutes of Past Meetings, and So On, That Are Kept in Our Website, Which Serve As Records of All the Speeches We Made Previously

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 8 January 2014 5087 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 8 January 2014 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. 5088 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 8 January 2014 THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. -

Application for Closed Area Permit / Closed Road Permit (Police Use Only)

MEMO From _________________________________________ _ TO: Commissioner of Police Ref ( ) in _________________________________ _ (Attn: SP OPS PHQ ) Tel. No. ___________________________________________ Your Ref. ___________________________________________ Fax No. ___________________________________________ Dated ______________ Fax. No. 2865 9786 Date ___________________________________________ Total Pages __________________________________________ Application No. Application for Closed Area Permit / Closed Road Permit (Police Use Only) I hereby apply for the staff of our department and/or the staff from our contractor and/or their vehicle(s) to enter the Frontier Closed Area (FCA):- Part I (Please ‘tick(√)’the appropriate boxes) CAP: □ Lo Wu □ Lok Ma Chau □ Man Kam To □ Sha Tau Kok □ Ta Kwu Ling □ ALL □ Chung Ying St. □ Shenzhen Bay Port CRP: □ Lo Wu □ Lok Ma Chau □ Man Kam To □ Sha Tau Kok □ Ta Kwu Ling □ ALL □Shenzhen Bay Port For the period : From to (both dates inclusive) Total visit frequency : For the following reason: (Please ‘tick (√)’the appropriate box and delete as appropriate) Regular Duty Purpose (Please specify) Site Visit / Urgent Visit / Surprise Check ____________________________________________ Delivery / Facility Maintenance Others (please specify) ------ Details of the applicant(s) applied for Closed Area Permit are listed in Annex A ------ Details of the vehicle(s) required for Closed Road Permit are listed in Annex B Declaration by the Applicant I declare that the contents as stipulated in Security Bureau Circular No.7/99 have been observed and fully understood by the applicants. I understand that the above application should be submitted at least 14 working days in advance of the applied period. I understand that for an applied period of over one month, the visit frequency must be over twice per month.