Crooked House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OR KILL ME.Pdf

OR KILL ME!! Heresies, Rants, Sermons, Epistles, and Other Foul Words of The Good Reverend Roger 1 or kill me 2 CONTENTS PART ONE: Sermons 3 PART TWO: Heresies 85 PART THREE:Millions of Screaming Yahoos 98 PART FOUR: Epistles 168 PART FIVE: Life in the Age of the Dumb 182 PART SIX: Rants 203 PART SEVEN: Miscellaneous 233 or kill me 3 PART ONE: ROGER’S SERMONS or kill me 4 Rev Roger Sermon #1: A rant/sermon from the Good Reverend Roger Originally posted January 23, 2003 Brothers, Sisters, and Others, I speak to you (or rather write to you) tonight about the dangers of backsliding...For are there not those who go about quoting the Principia and St Wilson the Obscure; and do so having forgotten the message behind those glib words? To be a discordian is far more than rote memorization of an author's words... It is, in essence, one of the few remaining ways in which a person might be free. To lapse into dogma and the random spouting of anothers word is to deny that freedom! Can I get an "Amen"? In this new decade, our rights are stripped from us inch by inch, and day by day. We can now be detained (no more fun for YOU, Bubba...Ever) without counsel, our mail and our email can be read sans warrant, and even the so-called "opposition" has caved into this fascism, Eris damn their black souls. They would have ORDER. Law. Regulation. In short, they would have all that we disdain; truly, they would make the WORLD itself grey, had they the power (and they might yet). -

Swimming As Punching Their Way Through Water

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Feiwel and Friends ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e- book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Diarmuid the end You’d think it would feel weird being nearly naked in front of so many people, but it doesn’t. I ping my swimsuit straps for luck, once right, twice left, walk out poolside, and take a deep breath, inhaling the familiar tang of chlorine and feet. It sounds gross, but that smell is so exciting. I’m where I belong. I’m one of the fastest swimmers in my county. That’s why I’m here—trying out for a High Performance Training Camp that will set me on my way to Team Great Britain. I’ve wanted this for as long as I can remember. So … you know, no pressure, not a big deal, whev. I think I’m sweating inside my ears. I pad along the side of the pool, watching the heat before mine. Older swimmers power up and down; they look so strong—they’re not so much swimming as punching their way through water. -

The Truth About Elvis” Movie Website from Back in March 2007 – This Is Reproduced Here for Educational Purposes Only

THIS IS TEXT FROM THE RESEARCH SECTION OF “THE TRUTH ABOUT ELVIS” MOVIE WEBSITE FROM BACK IN MARCH 2007 – THIS IS REPRODUCED HERE FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY. PLEASE CHECK OUT THE GROUP ON FACEBOOK FOR MORE INFORMATION OR TO HELP WITH THE SEARCH FOR THE TRUTH. https://www.facebook.com/groups/48484318100/ OR MICKEY'S WEBSITE AT http://elvisconspiracy.webs.com/ Cheers & TCB! I'm going to post sightings, leads and research here. I'll post this information as I go along, so you can see some of the information I'm using to move forward. FROM ME: WE REALLY APPRECIATE THE EMAILS WE RECEIVE FROM FANS. LET US KNOW IF YOU HAVE ANY INTERESTING NEWS. THANKS, ADAM 3/14/07 Hi Adam, I finally had the chance to read "Elvis & Me by Priscilla and thought I'd share a little info with you. As I read the book, I really find it hard to believe that Priscilla would put some of the information she has in the book if Elvis was alive. There is quite a bit of their intimacy moments in the book and knowing what I've read about the two of them, it's hard to believe Priscilla even sharing this information. All I know is that I have very mixed feelings about the whole Elvis thing. Is it a money gimmick and/or just to keep Elvis and themselves in the limelight light. I do know that people are out to make a buck off of him. Some of those addresses on People Search are phony and they shouldn't be allowed to rip people off by using his middle initial and date of birth. -

Festival Di Majano 2020 Sum 41

COMUNICATO STAMPA Zenit srl in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismo FVG, nell’ambito della 60° edizione del Festival di Majano presenta FESTIVAL DI MAJANO 2020 LE STAR DEL PUNK SUM 41 IN CONCERTO AL 60° FESTIVAL DI MAJANO FRA LE BAND CHE HANNO SEGNATO LA STORIA DEL PUNK ROCK INTERNAZIONALE VENDENDO OLTRE 15 MILIONI DI DISCHI NEL MONDO HANNO FIRMATO ALBUM MEMORABILI COME “ALL KILLER NO FILLER” (2001) E SUPER HIT COME “IN TOO DEEP” E “STILL WAITING” SARANNO SUL PALCO DI MAJANO IL PROSSIMO 14 AGOSTO PER L’UNICA DATA NEL NORD ITALIA DEL LORO NUOVO TOUR MONDIALE #FestivalMajano60 SUM 41 “No Personal Space Tour” Venerdì 14 agosto 2020, inizio ore 21.30 MAJANO (UDINE), AREA CONCERTI FESTIVAL Biglietti in vendita online su Ticketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita autorizzati dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. Info e punti vendita autorizzati su www.azalea.it Secondo annuncio internazionale per il Festival di Majano, storica rassegna musicale, culturale e enogastronomica del Friuli Venezia Giulia che festeggia nel 2020 i suoi 60° anni attestandosi come una delle manifestazioni più longeve e di successo dell’estate. Dopo il concerto con protagonisti i Bad Religion, i cui biglietti sono andati in vendita nelle scorse settimane, ecco ufficializzato oggi l’arrivo delle star del punk rock mondiale Sum 41, che saranno straordinariamente in concerto sul palco dell’Aera Concerti il prossimo venerdì 14 agosto 2020. I biglietti per questo nuovo grande appuntamento musicale dell’estate, organizzato da Zenit srl, in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismoFVG e Hub Music Factory, saranno in vendita online su Tiketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita del circuito dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Here Without You 3 Doors Down

Links 22 Jacks - On My Way 3 Doors Down - Here without You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - When I m Gone 30 Seconds to Mars - City of Angels - Intermediate 30 Seconds to Mars - Closer to the edge - 16tel und 8tel Beat 30 Seconds To Mars - From Yesterday https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpG7FzXrNSs 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings and Queens 30 Seconds To Mars - The Kill 311 - Beautiful Disaster - - Intermediate 311 - Dont Stay Home 311 - Guns - Beat ternär - Intermediate 38 Special - Hold On Loosely 4 Non Blondes - Whats Up 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 9-8tel Nine funk Play Along A Ha - Take On Me A Perfect Circle - Judith - 6-8tel 16tel Beat https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTgKRCXybSM A Perfect Circle - The Outsider ABBA - Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA - Mamma Mia - 8tel Beat Beginner ABBA - Super Trouper ABBA - Thank you for the music - 8tel Beat 13 ABBA - Voulez Vous Absolutum Blues - Coverdale and Page ACDC - Back in black ACDC - Big Balls ACDC - Big Gun ACDC - Black Ice ACDC - C.O.D. ACDC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC - Evil Walks ACDC - For Those About To Rock ACDC - Givin' The Dog A Bone ACDC - Go Down ACDC - Hard as a rock ACDC - Have A Drink On Me ACDC - Hells Bells https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFJFonWfBBM ACDC - Highway To Hell ACDC - I Put The Finger On You ACDC - It's A Long Way To The Top ACDC - Let's Get It Up ACDC - Money Made ACDC - Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution ACDC - Rock' n Roll Train ACDC - Shake Your Foundations ACDC - Shoot To Thrill ACDC - Shot Down in Flames ACDC - Stiff Upper Lip ACDC - The -

She Didn't See It Coming

She didn’t see it coming She didn’t see it coming First published July 15, 2018. New edition published May 2019. Please note: story was updated in May 2019 because I wanted to improve I so if you read it before it has changed. Plot remains the same but has been extensively elaborated and full chapters added. 2 She didn’t see it coming About the story Are we really sure Bones died a far too early death for such a charismatic character? Nah, don’t think so. This is my alternative take on Season 3. The story begins during the Bangladesh tour at the end of episode 5, when Bones has just been blown to pieces in front of 2 section at a garden party. I was very unhappy about the turn of events, so out of pure frustration I decided to have try at writing fanfiction. I anyway always have side stories about movie characters I like running in my head, so why not write them down. The past is basically canon. Credits to Tony Grounds and BBC for the characters, I just let them live another life for a while here. The reason I updated eight months after first publishing it, was that at a re-read I realised I could do better and felt that my only full- length Bones & Georgie fic deserved as good as I got. This is a hot story. if you don’t like a bit of smut you may need to skip parts, but above all it is a love story. -

Bookviewcafe-Samplechapters.Pdf

Book View Cafe Sample Chapters Table of Contents Lacing up for Murder........................................................4 Irene Radford..........................................................................4 Chapter 1.......................................................................................5 Chapter 2.....................................................................................12 Chapter 3.....................................................................................18 Revise the World.............................................................24 Brenda W. Clough.................................................................24 Epigraph.......................................................................................25 Part 1............................................................................................26 Fool’s War..........................................................................37 Sarah Zettel..........................................................................37 Chapter One — Preparations....................................................38 Camelot’s Blood...............................................................94 Sarah Zettel..........................................................................94 Prologue.......................................................................................95 Chapter One................................................................................99 Taco Del And The Fabled Tree Of Destiny....................................................104 -

Wordperfect Document

TODD KING/NOVA ETH PUBLISHING ©1997 1339 CHARWOOD DRIVE Todd King & BOGALUSA, LA. 70427 Nova Eth Publishing THE SEVEN STARS TODD KING 1 KING/THE SEVEN STARS I If I Die Before I Wake... II I Was Me, But Now He’s Gone... III The Gathering... IV Electric Bard... V Remembrance Of Things Past... VI No Remorse... VII Transcend The Boundaries... VIII See You In The Next World, And Don’t Be Late... IX For All Eternity... X Diary Of A Madman... XI Sad But True... XII Love, Hate, Love... XIII Most Of This Is Memory Now... XIV I Remember Now... XV The Abyss Also Gazes... XVI Creeping Death... XVII Dark Storm Rising... XVIII Garden... XIX Enter The Dragon... XX Electric Angels Sing... XXI Afterimages... 2 KING/THE SEVEN STARS “A little while, a moment of rest upon the wind, and another woman shall bear me. Farewell to you and the youth I have spent with you. It was but yesterday we met in a dream. You have sung to me in my aloneness, and I of your longings have built a tower in the sky. But now our sleep has fled and our dream is over, and it is no longer dawn.” Kahlil Gibran —“The Prophet” 3 KING/THE SEVEN STARS If I Die Before I Wake... “Tatternorn!” who? “Move it! Move it! Get your ass in gear!” me, move? but i’m comfortable and warm and... “Go!” Race of six amber flies, buzzing by. ...who the hell are those guys? Black shadow-fog...cloying, grasping. waitaminnit...how can i go if i can’t feel my feet? “Go!” screw you...this is a dream...i’m dreaming...this is only a dr— “Tatternorn! Look out!” i’m not— Blast of molten blackness. -

New Cuts, Old Wounds ~

~ New Cuts, Old Wounds ~ by Shea K. Disclaimer: Welcome to another original story by this lunatic. This is the sequel to Scarred for Life. The story and the characters are mine. Do not use them without my permission. Also, any and all characters, events, and situations found in these stories are fictional. If there are any similarities between these things and real people, events, and situations, it is purely a coincidence. General warning: eventually there's talk of child abuse and there is some mild violence and lots of extreme language. I'm sure you know there will be a sexual relationship between two women, but if you don't know this is me warning you. There will be a sexual relationship between two women in this story. Get out while you still can! Special thanks to my betas, RevSrVixena and Ken-zero. Find yourself wanting to see more from this lunatic? Probably not, I know. But, if you are, then you can find more of my insanity here for fanfics: http://www.fanfiction.net/u/932292/ and for more original work here: http://www.fictionpress.com/u/576301/ Contact the lunatic at: [email protected] and lemme know what you think of the story. Thanks and enjoy. 1: Rebirth The spring was back, bringing warmth and promise along with it. For the first time in a long time, Dane Wolfe-or Danny as she was called more often than not now-found that she could feel that vibe. For the first time, she could understand why people enjoyed the spring. -

Il Pianoforte: Mostra Sulla Storia E Spazio Per Giovani Concertisti E Scuole Del Territorio

Pordenone : il pianoforte: mostra sulla storia e spazio per giovani concertisti e scuole del territorio Centro Commerciale Adriatico 2 Portogruaro L’evoluzione del pianoforte mostra dedicata alla storia del pianoforte spazio a disposizione dei giovani concertisti Focus sulla storia di uno degli strumenti musicali tra i più amati e popolari al Centro Commerciale Adriatico 2 di Portogruaro, grazie alla collaborazione di Biasin Musical Instruments e Yamaha. In programma fino al 16 settembre una mostra, “L’evoluzione del pianoforte” che accompagna il visitatore a conoscere l’evoluzione del pianoforte dai primi del 900 fino ai giorni nostri e uno spazio a giovani pianisti che avranno l’opportunità di esibirsi nei differenti corner allestiti lungo la galleria del centro. Da parte degli organizzatori infatti c’è la volontà non solo di offrire un approfondimento culturale su un argomento poco conosciuto, ma anche di sopperire alla mancanza di spazi e occasioni per esibirsi e mettersi alla prova col pubblico da parte dei giovani musicisti, che nel caso del pianoforte, date le dimensioni e le difficoltà del trasposto appaiono ancor più evidenti. Fino al 1600 lo strumento più usato dotato di tastiera e corde era il clavicembalo, che però aveva dei limiti nella dinamica, nell’espressività musicale e nel tocco. L’inventore del pianoforte Bartolomeo Cristofori, un costruttore di clavicembali di Padova, sostituì i saltarelli con dei martelletti indipendenti, inventando il fortepiano, che venne sviluppato in Europa durante tutto il 1700. Nel 1800 si cominciarono a produrre pianoforti a coda e la meccanica del moderno pianoforte raggiunse la perfezione. Ogni azienda ha sviluppato un ambito di ricerca per migliorare e innovare i propri pianoforti. -

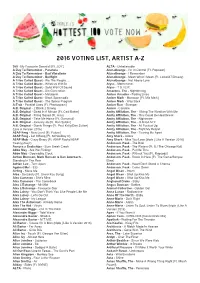

Artist A-Z, Triple J's 2016 Voting List

2016 VOTING LIST, ARTIST A-Z 360 - My Favourite Downfall {Ft. JOY.} ALTA - Unbelievable A Day To Remember - Paranoia AlunaGeorge - I'm In Control {Ft. Popcaan} A Day To Remember - Bad Vibrations AlunaGeorge - I Remember A Day To Remember - Bullfight AlunaGeorge - Mean What I Mean {Ft. Leikeli47/Dreezy} A Tribe Called Quest - We The People.... AlunaGeorge - Not Above Love A Tribe Called Quest - Whateva Will Be Alyss - Motherland A Tribe Called Quest - Solid Wall Of Sound Alyss - T S I E R A Tribe Called Quest - Dis Generation Amazons, The - Nightdriving A Tribe Called Quest - Melatonin Amber Arcades - Fading Lines A Tribe Called Quest - Black Spasmodic Amber Mark - Monsoon {Ft. Mia Mark} A Tribe Called Quest - The Space Program Amber Mark - Way Back A-Trak - Parallel Lines {Ft. Phantogram} Amber Run - Stranger A.B. Original - 2 Black 2 Strong Aminé - Caroline A.B. Original - Dead In A Minute {Ft. Caiti Baker} Amity Affliction, The - I Bring The Weather With Me A.B. Original - Firing Squad {Ft. Hau} Amity Affliction, The - This Could Be Heartbreak A.B. Original - Take Me Home {Ft. Gurrumul} Amity Affliction, The - Nightmare A.B. Original - January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Amity Affliction, The - O.M.G.I.M.Y. A.B. Original - Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly/Dan Sultan} Amity Affliction, The - All Fucked Up {Live A Version 2016} Amity Affliction, The - Fight My Regret A$AP Ferg - New Level {Ft. Future} Amity Affliction, The - Tearing Me Apart A$AP Ferg - Let It Bang {Ft. ScHoolboy Q} Amy Shark - Adore A$AP Mob - Crazy Brazy {Ft.