ABSTRACT ALL OUR FATHERS by Nicholas D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glitz and Glam

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:17 PM Glitz and glam The biggest celebration in filmmaking tvspotlight returns with the 90th Annual Academy Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Awards, airing Sunday, March 4, on ABC. Every year, the most glamorous people • For the week of March 3 - 9, 2018 • in Hollywood stroll down the red carpet, hoping to take home that shiny Oscar for best film, director, lead actor or ac- tress and supporting actor or actress. Jimmy Kimmel returns to host again this year, in spite of last year’s Best Picture snafu. OMNI Security Team Jimmy Kimmel hosts the 90th Annual Academy Awards Omni Security SERVING OUR COMMUNITY FOR OVER 30 YEARS Put Your Trust in Our2 Familyx 3.5” to Protect Your Family Big enough to Residential & serve you Fire & Access Commercial Small enough to Systems and Video Security know you Surveillance Remote access 24/7 Alarm & Security Monitoring puts you in control Remote Access & Wireless Technology Fire, Smoke & Carbon Detection of your security Personal Emergency Response Systems system at all times. Medical Alert Systems 978-465-5000 | 1-800-698-1800 | www.securityteam.com MA Lic. 444C Old traditional Italian recipes made with natural ingredients, since 1995. Giuseppe's 2 x 3” fresh pasta • fine food ♦ 257 Low Street | Newburyport, MA 01950 978-465-2225 Mon. - Thur. 10am - 8pm | Fri. - Sat. 10am - 9pm Full Bar Open for Lunch & Dinner FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:19 PM 2 • Newburyport Daily News • March 3 - 9, 2018 the strict teachers at her Cath- olic school, her relationship with her mother (Metcalf) is Videoreleases strained, and her relationship Cream of the crop with her boyfriend, whom she Thor: Ragnarok met in her school’s theater Oscars roll out the red carpet for star quality After his father, Odin (Hop- program, ends when she walks kins), dies, Thor’s (Hems- in on him kissing another guy. -

The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo" (2016). Student Publications. 438. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/438 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 438 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Abstract The se cape of thousands of war criminals to Argentina and throughout South America in the aftermath of World War II is a historical subject that has been clouded with mystery and conspiracy. Lucía Puenzo's film, The German Doctor, utilizes this historical enigma as a backdrop for historical fiction by imagining a family's encounter with Josef Mengele, the notorious SS doctor from Auschwitz who escaped to South America in 1949 under a false identity. -

Star Channels, April 19-25, 2020

APRIL 19 - 25, 2020 staradvertiser.com LOWKEY AMAZING HBO’s acclaimed dramedy Insecure kicked off its fourth season last week, and fans are eager to see more from its powerful leading ladies, Issa (Issa Rae) and Molly (Yvonne Orji), who have been through a veritable plague of drama over the past three years. Airing Sunday, April 19, on HBO. ¶Olelo has gone mobile. Watch everything from local events to live coverage of the State Legislature, anytime, anywhere. Download the Ҋũe^ehFh[be^:iibgma^:iiLmhk^hk@hh`e^IeZr' olelo.org 590198_MobileApp_2.indd 1 3/5/20 1:15 PM ON THE COVER | INSECURE No man, no job, no problem ‘Insecure’ comes through to believe the current installment of the garner further attention and receive Golden “Insecure” saga will be anything but lowkey. Globe or Emmy nominations? Let’s slow in uncertain times The 10-episode season focuses on re- down and look at the tangibles before get- turning main characters, Issa (Issa Rae, ting too carried away with the questions. By Dana Simpson “The Misadventures of Awkward Black For starters, Issa is without a job and with- TV Media Girl”) and her best friend, Molly (Yvonne out a man — a situation that may be haunt- Orji, “Nightschool,” 2018), who have been ingly relatable for any single person tem- earing up for another year of turmoil through, well, let’s face it, a veritable plague porarily out of work during these strange and wit after a year-and-a-half-long of drama over the past three years. From times of social isolation. -

OR KILL ME.Pdf

OR KILL ME!! Heresies, Rants, Sermons, Epistles, and Other Foul Words of The Good Reverend Roger 1 or kill me 2 CONTENTS PART ONE: Sermons 3 PART TWO: Heresies 85 PART THREE:Millions of Screaming Yahoos 98 PART FOUR: Epistles 168 PART FIVE: Life in the Age of the Dumb 182 PART SIX: Rants 203 PART SEVEN: Miscellaneous 233 or kill me 3 PART ONE: ROGER’S SERMONS or kill me 4 Rev Roger Sermon #1: A rant/sermon from the Good Reverend Roger Originally posted January 23, 2003 Brothers, Sisters, and Others, I speak to you (or rather write to you) tonight about the dangers of backsliding...For are there not those who go about quoting the Principia and St Wilson the Obscure; and do so having forgotten the message behind those glib words? To be a discordian is far more than rote memorization of an author's words... It is, in essence, one of the few remaining ways in which a person might be free. To lapse into dogma and the random spouting of anothers word is to deny that freedom! Can I get an "Amen"? In this new decade, our rights are stripped from us inch by inch, and day by day. We can now be detained (no more fun for YOU, Bubba...Ever) without counsel, our mail and our email can be read sans warrant, and even the so-called "opposition" has caved into this fascism, Eris damn their black souls. They would have ORDER. Law. Regulation. In short, they would have all that we disdain; truly, they would make the WORLD itself grey, had they the power (and they might yet). -

Swimming As Punching Their Way Through Water

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Feiwel and Friends ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e- book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Diarmuid the end You’d think it would feel weird being nearly naked in front of so many people, but it doesn’t. I ping my swimsuit straps for luck, once right, twice left, walk out poolside, and take a deep breath, inhaling the familiar tang of chlorine and feet. It sounds gross, but that smell is so exciting. I’m where I belong. I’m one of the fastest swimmers in my county. That’s why I’m here—trying out for a High Performance Training Camp that will set me on my way to Team Great Britain. I’ve wanted this for as long as I can remember. So … you know, no pressure, not a big deal, whev. I think I’m sweating inside my ears. I pad along the side of the pool, watching the heat before mine. Older swimmers power up and down; they look so strong—they’re not so much swimming as punching their way through water. -

TV Listings SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2017

TV listings SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2017 11:40 Disneyʼs Aladdin 05:30 Henry Hugglemonster 06:00 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 13:10 The 7D 05:45 Zou Henry 13:20 Girl Meets World 06:00 Art Attack 06:55 E! News 13:45 Girl Meets World 06:30 Henry Hugglemonster 07:10 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 15:25 Jessie 06:45 Loopdidoo Henry 00:40 Mythbusters 15:50 Jessie 07:00 Zou 08:10 E! News 00:50 River Monsters 01:30 How Do They Do It? 16:15 Austin & Ally 07:15 Calimero 09:05 Botched 01:45 Bondi Vet 00:10 Hank Zipzer 01:55 Food Factory 00:35 Binny And The Ghost 16:40 Austin & Ally 07:30 Loopdidoo 09:55 Botched 02:40 Deadliest Snakes Of South 02:20 Mythbusters 17:05 Descendants Wicked World 07:45 Henry Hugglemonster 10:45 Mariahʼs World Africa 01:00 Violetta 03:10 Alien Encounters 01:45 The Hive 17:10 Elena Of Avalor 08:00 My Friends Tigger & Pooh 13:15 E! News 03:35 Tanked 04:00 Da Vinciʼs Machines 17:35 Stuck In The Middle 08:25 Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 13:45 Celebrity Style Story 04:25 Great Animal Escapes 01:50 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 04:48 Mythbusters Witch 18:00 Frozen: Magic Of The Northern 08:50 Goldie & Bear 15:15 Keeping Up With The 05:15 Gator Boys 05:36 How Do They Do It? Lights 09:15 Miles From Tomorrow Kardashians 06:02 River Monsters 02:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 06:00 Food Factory Witch 18:25 The Incredibles 09:30 Jake And The Never Land 16:05 Revenge Body With Khloe 06:49 Deadliest Snakes Of South 06:24 Mythbusters 20:25 Star Darlings Pirates Kardashian Africa 02:40 Hank Zipzer 07:12 Alien Encounters 03:05 Binny And The Ghost -

The Truth About Elvis” Movie Website from Back in March 2007 – This Is Reproduced Here for Educational Purposes Only

THIS IS TEXT FROM THE RESEARCH SECTION OF “THE TRUTH ABOUT ELVIS” MOVIE WEBSITE FROM BACK IN MARCH 2007 – THIS IS REPRODUCED HERE FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY. PLEASE CHECK OUT THE GROUP ON FACEBOOK FOR MORE INFORMATION OR TO HELP WITH THE SEARCH FOR THE TRUTH. https://www.facebook.com/groups/48484318100/ OR MICKEY'S WEBSITE AT http://elvisconspiracy.webs.com/ Cheers & TCB! I'm going to post sightings, leads and research here. I'll post this information as I go along, so you can see some of the information I'm using to move forward. FROM ME: WE REALLY APPRECIATE THE EMAILS WE RECEIVE FROM FANS. LET US KNOW IF YOU HAVE ANY INTERESTING NEWS. THANKS, ADAM 3/14/07 Hi Adam, I finally had the chance to read "Elvis & Me by Priscilla and thought I'd share a little info with you. As I read the book, I really find it hard to believe that Priscilla would put some of the information she has in the book if Elvis was alive. There is quite a bit of their intimacy moments in the book and knowing what I've read about the two of them, it's hard to believe Priscilla even sharing this information. All I know is that I have very mixed feelings about the whole Elvis thing. Is it a money gimmick and/or just to keep Elvis and themselves in the limelight light. I do know that people are out to make a buck off of him. Some of those addresses on People Search are phony and they shouldn't be allowed to rip people off by using his middle initial and date of birth. -

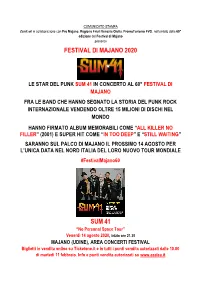

Festival Di Majano 2020 Sum 41

COMUNICATO STAMPA Zenit srl in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismo FVG, nell’ambito della 60° edizione del Festival di Majano presenta FESTIVAL DI MAJANO 2020 LE STAR DEL PUNK SUM 41 IN CONCERTO AL 60° FESTIVAL DI MAJANO FRA LE BAND CHE HANNO SEGNATO LA STORIA DEL PUNK ROCK INTERNAZIONALE VENDENDO OLTRE 15 MILIONI DI DISCHI NEL MONDO HANNO FIRMATO ALBUM MEMORABILI COME “ALL KILLER NO FILLER” (2001) E SUPER HIT COME “IN TOO DEEP” E “STILL WAITING” SARANNO SUL PALCO DI MAJANO IL PROSSIMO 14 AGOSTO PER L’UNICA DATA NEL NORD ITALIA DEL LORO NUOVO TOUR MONDIALE #FestivalMajano60 SUM 41 “No Personal Space Tour” Venerdì 14 agosto 2020, inizio ore 21.30 MAJANO (UDINE), AREA CONCERTI FESTIVAL Biglietti in vendita online su Ticketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita autorizzati dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. Info e punti vendita autorizzati su www.azalea.it Secondo annuncio internazionale per il Festival di Majano, storica rassegna musicale, culturale e enogastronomica del Friuli Venezia Giulia che festeggia nel 2020 i suoi 60° anni attestandosi come una delle manifestazioni più longeve e di successo dell’estate. Dopo il concerto con protagonisti i Bad Religion, i cui biglietti sono andati in vendita nelle scorse settimane, ecco ufficializzato oggi l’arrivo delle star del punk rock mondiale Sum 41, che saranno straordinariamente in concerto sul palco dell’Aera Concerti il prossimo venerdì 14 agosto 2020. I biglietti per questo nuovo grande appuntamento musicale dell’estate, organizzato da Zenit srl, in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismoFVG e Hub Music Factory, saranno in vendita online su Tiketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita del circuito dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

TV Listings SATURDAY, APRIL 1, 2017

TV listings SATURDAY, APRIL 1, 2017 03:00 Man Fire Food 01:20 The Unexplained Files 03:30 Man Fire Food 02:10 How The Earth Works 04:00 Chopped 03:00 The Big Brain Theory 05:00 Guy's Grocery Games 03:48 Mythbusters 06:00 Roadtrip With G. Garvin 04:36 How Do They Do It? 06:30 Roadtrip With G. Garvin 05:00 Food Factory 07:00 Chopped 05:24 The Unexplained Files 08:00 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 06:12 How The Earth Works 08:30 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 07:00 How Do They Do It? 09:00 The Pioneer Woman 07:26 Food Factory 09:30 The Pioneer Woman 07:50 Food Factory 10:00 Siba's Table 08:14 Food Factory 10:30 Siba's Table 08:38 Food Factory 11:00 Anna Olson: Bake 09:02 Food Factory 11:30 Anna Olson: Bake 09:26 How Do They Do It? 12:00 Man Fire Food 09:50 How Do They Do It? 12:30 Man Fire Food 10:14 How Do They Do It? 13:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 10:38 How Do They Do It? 13:30 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 11:02 How Do They Do It? 14:00 Chopped 11:26 How The Earth Works 15:00 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 12:14 How The Earth Works 15:30 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 13:02 How The Earth Works 16:00 The Pioneer Woman 13:50 How The Earth Works 16:30 The Pioneer Woman 14:38 How The Earth Works 17:00 Siba's Table 15:26 Mythbusters 17:30 Siba's Table 16:14 Mythbusters 18:00 Anna Olson: Bake 17:02 Mythbusters 18:30 Anna Olson: Bake 17:50 Mythbusters 19:00 Man Fire Food 18:40 Mythbusters 19:30 Man Fire Food 19:30 NASA's Unexplained Files 20:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 20:20 Sport Science 20:30 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 21:10 -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

The Biglittle Times®

THE BIG LITTLE TIMES® __________________________________________________ SUMMER EDITION BIG LITTLE BOOK COLLECTOR’S CLUB JUNE 2012 P.O. BOX 1242 DANVILLE, CALIFORNIA 94526 _______________________________________________________________________________________ JANE ARDEN AND THE VANISHED PRINCESS WHITMAN BETTER LITTLE BOOK #1498 (1938) BUCK ROGERS IN THE WAR WITH THE PLANT VENUS WHITMAN BETTER LITTLE BOOK #1437 (1938) Back Front Cover Cover Beginning this year, the Big Little Book Club is publishing its Big Little Times newsletter on a semi-annual basis. The issue is larger than previous issues. It contains more articles and lots more collecting information for Club Members to read and enjoy. The next issue will be in December • • • For this issue, Jon Swartz, Member #1287, has written an extensive article on the Buck Rogers Big Little Books and the many collectibles that were produced during the heyday of the comic strip and radio program. The history of the character, which began in 1928, reveals that he has never fully lost his appeal to subsequent generations. The pictures of premiums that accompany the article are from Jon’s extensive collection of Buck Rogers ephemera. • • • Walt Needham, Member #1102, has been a popular contributor of BLT articles for nearly 20 years. His carefully researched articles provide details that most collectors don’t know about the characters in the Big Little Books. In this issue Walt takes us on a journey through the world of Jane Arden, one of the earliest comic strip characters who exemplified the changing role of women in the American Society. Although Jane appeared in just one BLB, her comic book life lasted for many decades – from 1927 through 1968.