The Changes of Language Policies in Hong Kong Education in the Post-Colonial Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045 (1988)

www.lawcommission.gov.np Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045 (1988) Date of Authentication and Publication 2045.7.28 (13 Nov. 1988) Amendments : 1. Technical Education and Vocational 2050.2.27(9 May 1993) Training Council Act, 2049 (1993) 2. Education and Sports Related Some Nepal 2063.9.14(8 Jan.2006) Acts (Amendment) Act, 2063 (2006)1 3. Republic Strengthening and Some Nepal 2066.10.7 (21 Jan. 2010) Laws Amendment Act, 2066 (2010)2 Act Number 20 of the Year 2045(1988) An Act Made to Provide for the Establishment and Provision of Technical Education and Vocational Training Preamble : Whereas, it is expedient to establish and provide for the Technical Education and Vocational Training Council in order to manage technical education and vocational training in a planned manner and to make determination and accreditation of standards of skills, for the generation of basic and medium level technical human resources; 1 This Act came into force on 17 Shrwan 2063(2 Aug. 2006). 2 This Act came into force on 15 Jestha 2065 (28 June 2008) and " Prasati " has been deleted. 1 www.lawcommission.gov.np www.lawcommission.gov.np Now, therefore, be it enacted by His Majesty King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, on the advice and with the consent of the Rastriya Panchayat . 1. Short title and commencement : 1.1 This Act may be called as the "Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045(1989)". 1.2 This Act shall come into force on such a date as the Government of Nepal may appoint by publishing a Notification in the Nepal Gazette. -

Radio Television Hong Kong Performance Pledge 2015-16

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE 2015-16 This performance pledge summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Service Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public service broadcaster in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public service broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2015-16, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; and will receive advice from the Board of Advisors on issues pertaining to its terms of -

May 2008 Issue No. 24 HKI

Issue no. 24 HK May 2008 Newsletter Hong Kong Institute of Educational Research IE The Chinese University of Hong Kong In This Issue R Research Notes and Innovations 1 Research Notes and Innovations Evaluation Research on the Implementation of the Medium of Instruction Guidance for Secondary Schools 8 Research Programmes Principal Investigator: Professor Wing-kwong Tsang Programmes for Professional 8 Since September 1999, faculty members 1 of the Departments of Curriculum and Development Instruction (C&I) and Educational Administration and Policy (EAP), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, have carried out a longitudinal study to 10 Conferences, Seminars and evaluate the implementation of the Medium of Instruction Guidance for Public Lectures Secondary Schools (Guidance). The study is made up of three phases. The first two phases were commissioned by the then Education Department, the HKSAR 12 Development Projects government, 2 while the third phase is funded by the Public Policy Research (4009-PPR-2), the Research Grants Council of the University Grants 13 Research and Development Committee. The longitudinal study is by design an ex post facto policy-evalua- Centres tion research, which aims to assess the effects of the policy measure stipulated in the Guidance on secondary school students’ academic and psychosocial 15 Publications developments. The policy measure in point is the directive to mandate all secondary schools to “adopt Chinese for teaching all academic subjects, start- ing from their 1998/99 Secondary 1 intake” (Education Department, 1997, p. 4) unless they could prove another language (English) was as efficacious. The specific conditions for secondary schools to apply to use English as the medium 1 May 2008 Issue no. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 782 SO 007 248 AUTHOR Pyykkonen, Maija-Liisa, Ed. TITLE About the Finnish Educational System. Information

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 782 SO 007 248 AUTHOR Pyykkonen, Maija-Liisa, Ed. TITLE About the Finnish Educational System. Information Bulletin. INSTITUTION Finnish National Board of Education, Helsinki. Research and Development Bureau. PUB DATE Mar 73 NOTE 23p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 DESCRIPTORS *Comparative Education; *Educational Change; Educational Planning; Elementary Education; *Grade Organization; *Instructional Program Divisions; National Programs; Organization; *Organizational Change; Planning; Preschool Education; School Organization; School Planning; Secondary Education; Social Change; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS *Finland; Nationwide Planning ABSTRACT This Information Bulletin discusses the general reform of the Finnish education system, necessitated by events of the sixties, which included a larger number of students leaving the Primary Schools after grade four to enter the secondary level, the failure of Primary Schools to meet demands of basic education, and the closing of rural Primary Schools concommitant with the need for new urban Primary Schools in response to changes in population patterns. The old system consisted of eight years of compulsory schooling, beginning at the age of seven, divided into six years of Primary School and two to three years of Civic School, which specialized according to local needs and on the basis of general, vocational, and pre-orientational education. Secondary schools consisted of a five grade lover section, the Middle School, and a three grade upper section, the Gymnasium. The new system will include preschool education and a Comprehensive School covering the elementary years, replacing Primary, Civic, and Middle Schools. Teacher training also will be reformed, taking place at the University within education departments rather than in training schools.(JH) INFORMATION NATIONAL BOARD OF EDUCATION Research and Development Bureau Finland BULLETIN U S MENT OF HEALTH. -

The Benefits of Patronage: How Political Appointments Can Enhance

The benefits of patronage: How political appointments can enhance bureaucratic accountability and effectiveness∗ Guillermo Toraly June 11, 2021 Latest version here Abstract The political appointment of bureaucrats is typically seen as a rent-seeking strategy that helps politicians sustain clientelistic networks and manipulate public administration to their ad- vantage. I argue that political appointments can also increase bureaucratic accountability and effectiveness because they provide political and social connections between bureaucrats and politicians. These connections grant access to material and non-material resources, enhance monitoring, facilitate the application of sanctions and rewards, align priorities and incentives, and increase mutual trust. In certain conditions, political appointments can thus enhance bureaucrats’ accountability and effectiveness in public service delivery. I test this theory us- ing data on Brazilian municipal governments, leveraging two quasi-experiments, two original surveys of bureaucrats and politicians, and in-depth interviews. The findings challenge the traditional view that patronage is universally detrimental to development, and highlight how political appointments and connections can be leveraged to enhance public service delivery. ∗I am indebted to Ben Ross Schneider, Lily Tsai and Daniel Hidalgo for invaluable advice and guidance throughout the project. For useful comments I also thank Julián Aramburu, Felipe Barrera-Osorio, Héctor Blanco, Sarah Brierley, Josh Clinton, Julia Smith Coyoli, Aditya -

Information Sheet on Special Education

EDUCATION BUREAU Information Sheet SPECIAL EDUCATION The Government adopts a dual-track mode in providing special education. The Education Bureau (EDB) will, subject to the assessment and recommendation of specialists and the consent of parents, refer students with more severe or multiple disabilities to aided special schools for intensive support services. Other students with special educational needs will attend ordinary schools. From the perspective of the education profession and with due consideration of the learning needs of students, the EDB has been reviewing the development of special education and injecting resources to enhance the quality of education. Schools strive to help students overcome their limitations and difficulties, attain the learning level in accordance with their abilities, and realise their potential at different developmental stages so that they can gradually become independent persons with adaptability and the learning to learn capabilities to embrace the challenges in life. Categories and Number of Special Schools In the 2021/22 school year (as of September 2021), there are 62 aided special schools in Hong Kong: Total No. No. of Schools Category of with Boarding Schools Section School for Children with Intellectual Disability (ID)1 43 16 School for Children with Visual Impairment (VI) 2 2 School for Children with Hearing Impairment (HI) 1 1 School for Children with Physical Disability (PD) 7 4 School for Social Development (SSD) 8 (7) 2 Hospital School3 1 - Total : 62 23 / (7) 2 1. Schools for children with ID provide educational service for children with mild ID, children with moderate ID and/or children with severe ID in accordance with the missions of respective schools. -

Aviation Education and Training Disclaimer

AVIATION EDUCATION AND TRAINING DISCLAIMER Austrade does not endorse or guarantee the performance or suitability of any introduced party or accept liability for the accuracy or usefulness of any information contained in this Report. Please use commercial discretion to assess the suitability of any business introduction or goods and services offered when assessing your business needs. Austrade does not accept liability for any loss associated with the use of any information and any reliance is entirely at the user’s discretion. © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available through the Australian Trade and Investment Commission. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Marketing Manager, Austrade, GPO Box 5301, Sydney NSW 2001 or by email to [email protected] Publication date: February 2017 Image courtesy of Flight Training Adelaide Companies and Capabilities (page 12 to 19) updated: June 2018 2 AVIATION EDUCATION AND TRAINING LAUNCHING INTERNATIONAL AVIATION CAREERS AVIATION EDUCATION AND TRAINING 3 INDUSTRY From fixed and rotary wing pilot training, to broader OVERVIEW aviation training that includes engineering, maintenance COMPANIES and air traffic management, Australia offers internationally AND CAPABILITIES approved programs. FURTHER The Australian aviation sector is well include providing transportation safety and respected, with a long and distinguished security assistance to Indonesia, Papua New INFORMATION history dating back to the early days of Guinea and several Pacific Island countries flight. Australia’s geographic size, vast covering areas such as technical support, interior and considerable distance from training, supply of personnel and air traffic trading partners have required air transport management services. -

Mazzei Flying Service Flight Training Pioneer Focuses on Training Flight Instructors

4th Quarter 2010 Mazzei Flying Service Flight Training Pioneer Focuses on Training Flight Instructors Also Inside • Health Care Reform and Small Permit No. 1400 No. Permit Silver Spring, MD Spring, Silver PAID Business—Who Won? U.S. Postage Postage U.S. Standard PRESORT PRESORT • Aviation in the Blood • California’s Flight Training Saga GLOBAL SUPPLIER OF AVIATION FUEL AND SERVICES Contract Fuel • Pilot Incentive Programs • Fuel Quality Assurance • Refueling Equipment Aviation Insurance • Fuel Storage Systems • Flight Planning and Trip Support TRIP SUPPORT 800.521.4106 • www.avfuel.com • facebook.com/avfuel • twitter.com/AVFUEL Jet Aviation and Midcoast Aviation: A global MRO network that safeguards you and your investment Strength, stability and skill: three benefi ts you gain when working with Jet Aviation and our U.S. affi liate, Midcoast Aviation. Two brands. One team you can rely on. Solid ownership, 43 years experience and an unsurpassed level of talent – available at 17 independent MRO centers of excellence worldwide – offer you and your aircraft global support delivered with our uncompromising dedication to quality, safety and service. Whatever your aircraft type or size, whatever the work scope – routine inspection, unscheduled or heavy maintenance, overhaul or even structural repair or AOG services – we can help. Personalized to Perfection. www.jetaviation.com l www.midcoastaviation.com Jet Aviation l Basel l Boston/Bedford l Dubai l Dusseldorf l Geneva l Hannover Hong Kong l Jeddah l Kuala Lumpur l London Biggin Hill l Moscow Vnukovo Riyadh | Singapore l Teterboro l Zurich l Midcoast Aviation l St. Louis l Savannah 73076_216x279_MRO_ABJ_e.indd 1 24.03.10 08:50 B:8.75” T:8.5” S:7” The pleasure of your company is requested. -

Guidance Notes Application for Registration As an Elector in A

Guidance Notes Application for Registration as an Elector in a Functional Constituency and as a Voter in an Election Committee Subsector Education Registration and Electoral Office REO-GN1(2004)-Edu CONTENTS Page Number I. Introduction 1 II. Who is Eligible to Apply for Registration in the 2 Education Functional Constituency and its Corresponding Election Committee Subsector III. Who is Disqualified from being Registered 3 IV. How to Submit an Application 4 V. Further Enquiries 4 VI. Personal Information Collection Statement 4 VII. Language Preference for Election-related 5 Communications Appendix A List of Functional Constituencies and their 6 corresponding Election Committee Subsectors Appendix B Eligibility for registration in the Education 7 Functional Constituency and its corresponding Election Committee Subsector ****************************************************************** The Guidance Notes and application forms are obtainable from the following sources: (a) Registration and Electoral Office: (i) 10th Floor, Harbour Centre 25 Harbour Road Wan Chai Hong Kong (ii) 10th Floor, Guardian House 32 Oi Kwan Road Wan Chai Hong Kong (b) Registration and Electoral Office Website: www.info.gov.hk/reo/index.htm (c) Registration and Electoral Office Enquiry Hotline: 2891 1001 - 1 - I. Introduction If you are eligible, you may apply to be registered as :- an elector in this Functional Constituency (“FC”) and a voter in the corresponding subsector of the Election Committee (“EC”), i.e. a subsector having the same name as the FC, at the same time, OR an elector in this FC and a voter in ONE of the following EC subsectors, instead of in its corresponding EC subsector: (1) Chinese Medicine; (2) Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference; (3) Hong Kong Chinese Enterprises Association, OR an elector in ONE of the FCs listed in Appendix A, and a voter in either its corresponding EC subsector or ONE of the above EC subsectors. -

Radio Television Hong Kong

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE This leaflet summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public broadcaster in the HKSAR. Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2011-12, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; maximize return on government funding by further enhancing cost efficiency and productivity; continue to ensure staff handle public funds in a prudent and cost-effective -

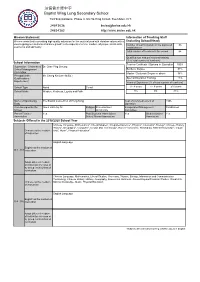

SAP Crystal Reports

浸信會永隆中學 Baptist Wing Lung Secondary School Tai Hing Gardens, Phase II, 6A Ho Hing Circuit, Tuen Mun, N.T. 24643638 [email protected] 24634382 http://www.bwlss.edu.hk Mission Statement Information of Teaching Staff We are committed to providing high quality education for the youth infused with christian values with a (including School Head) view to giving our students a balance growth in the aspects of ethics, intellect, physique, social skills, Number of teaching posts in the approved 56 aesthetics and spirituality. establishment Total number of teachers in the school 64 Qualifications and professional training (% of total number of teachers) School Information Teacher Certificate / Diploma in Education 100% Supervisor / Chairman of Dr. Chan Ping Cheung School Management Bachelor Degree 97% Committee Master / Doctorate Degree or above 38% Principal (with Mr. Cheng Kai Lam (M.Ed.) Qualifications / Special Education Training 13% Experiences) Years of Experience (% of total number of teachers) School Type Aided Co-ed 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years ≥10 years School Motto Wisdom, Kindness, Loyalty and Faith 9% 8% 83% Name of Sponsoring The Baptist Convention of Hong Kong Year of Commencement of 1996 Body Operation Area Occupied by the About 5800 Sq. M Religion Protestantism / Incorporated Management Established School Christianity Committee Parent-Teacher Yes Past Students' Association / Yes Student Union / Yes Association School Alumni Association Association Subjects Offered in the 2019/2020 School Year Chinese Language, Mathematics*, Liberal -

FCR(2005-06)39 on 13 January 2006

For discussion FCR(2005-06)39 on 13 January 2006 ITEM FOR FINANCE COMMITTEE HEAD 156 - GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT : EDUCATION AND MANPOWER BUREAU Subhead 700 General non-recurrent New Item “Grant to the Language Fund” Members are invited to approve a new commitment of $1,100 million for injection into the Language Fund. PROBLEM We need to strengthen the teaching and learning of English in our secondary schools and to support the wider use of Putonghua to teach the Chinese Language subject in primary and secondary schools. PROPOSAL 2. The Secretary for Education and Manpower (SEM) proposes to inject $1,100 million into the Language Fund (the Fund) to – (a) strengthen the teaching and learning of English in secondary schools, and (b) support the wider use of Putonghua to teach the Chinese Language subject in primary and secondary schools. JUSTIFICATION 3. There is an outstanding balance of $550 millionNote 1 in the Fund as at the end of November 2005. However, more than $489 million have been /earmarked ..... Note 1 A total of $1,400 million have been injected into the Fund since 1994. Added to this is a total interest income of $186 million accrued by the Fund over the years. Taking into account the total grants of $1,030 million already approved for various projects (of which $401 million has already been spent and $629 million has been committed for initiatives in progress) and $6 million already spent on other miscellaneous expenses, there was an outstanding balance of $550 million left in the Fund as at the end of November 2005.