Multicultural Education and Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045 (1988)

www.lawcommission.gov.np Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045 (1988) Date of Authentication and Publication 2045.7.28 (13 Nov. 1988) Amendments : 1. Technical Education and Vocational 2050.2.27(9 May 1993) Training Council Act, 2049 (1993) 2. Education and Sports Related Some Nepal 2063.9.14(8 Jan.2006) Acts (Amendment) Act, 2063 (2006)1 3. Republic Strengthening and Some Nepal 2066.10.7 (21 Jan. 2010) Laws Amendment Act, 2066 (2010)2 Act Number 20 of the Year 2045(1988) An Act Made to Provide for the Establishment and Provision of Technical Education and Vocational Training Preamble : Whereas, it is expedient to establish and provide for the Technical Education and Vocational Training Council in order to manage technical education and vocational training in a planned manner and to make determination and accreditation of standards of skills, for the generation of basic and medium level technical human resources; 1 This Act came into force on 17 Shrwan 2063(2 Aug. 2006). 2 This Act came into force on 15 Jestha 2065 (28 June 2008) and " Prasati " has been deleted. 1 www.lawcommission.gov.np www.lawcommission.gov.np Now, therefore, be it enacted by His Majesty King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, on the advice and with the consent of the Rastriya Panchayat . 1. Short title and commencement : 1.1 This Act may be called as the "Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045(1989)". 1.2 This Act shall come into force on such a date as the Government of Nepal may appoint by publishing a Notification in the Nepal Gazette. -

At Home in the World: Bridging the Gap Between Internationalization and Multicultural Education

Global Learning for All: The Fourth in a Series of Working Papers on Internationalizing Higher Education in the United States At Home in the World: Bridging the Gap Between Internationalization and Multicultural Education by Christa L. Olson, Rhodri Evans, and Robert F. Shoenberg Funded by the Ford Foundation AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION The Unifying Voice for Higher Education Global Learning for All: The Fourth in a Series of Working Papers on Internationalizing Higher Education in the United States At Home in the World: Bridging the Gap Between Internationalization and Multicultural Education by Christa L. Olson, Rhodri Evans, and Robert F. Shoenberg Funded by the Ford Foundation AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION The Unifying Voice for Higher Education © June 2007 American Council on Education ACE and the American Council on Education are registered marks of the American Council on Education. American Council on Education One Dupont Circle NW Washington, DC 20036 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Additional copies of this publication are available for purchase at www.acenet.edu/bookstore for $20.00 per copy, plus shipping and handling. Copies also may be purchased by contacting: ACE Fulfillment Service Department 191 Washington, DC 20055-0191 Phone: (301) 632-6757 Fax: (301) 843-0159 www.acenet.edu When ordering, please specify Item #311578. Table of Contents Foreword .................................................. iii Executive Summary ........................................... v Introduction ................................................ vii Our Choice of Language . -

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

Promotion of STEM Education

Preamble Promotion of STEM Education This document entitled Promotion of STEM Education – Unleashing Potential in Innovation is issued to solicit views and comments from various stakeholders in the education and other sectors of the community on the recommendations and proposed strategies for the promotion of STEM education among schools in Hong Kong. It should be read in conjunction with the separate Briefs for Updating the Science, Technology and Mathematics Education Key Learning Area (KLA) Curricula). The recommendations and strategies proposed in this document on promoting STEM education have a direct bearing on school-based curriculum development over the next decade, and chart the way forward for sustaining the ongoing renewal of the school curriculum. Comments and suggestions on this document are welcome and should be sent to the following by 4 January 2016: Chief Curriculum Development Officer (Science) Education Bureau Room E232, 2/F, East Block Education Bureau Kowloon Tong Education Services Centre 19 Suffolk Road Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong (Fax: 2194 0670 ; E-mail: [email protected]) Curriculum Development Council November 2015 Contents Introduction 1 Why is it Necessary to Promote STEM Education? 2 What is the Direction for Promoting STEM Education? 3 Guiding Principles for Promoting STEM Education……………..…….. 3 Aim and objectives of Promoting STEM Education……..…….............. 4 What are the Recommendations for STEM Education in Hong Kong? 5 Strengthening the Ability to Integrate and Apply……………………….. 5 Approaches for Organising Learning Activities on STEM Education.… 6 Teacher Collaboration and Community Partnership……………......…... 7 What are the Strategies for Promoting STEM Education? 8 Renew the Curricula of Science, Technology and Mathematics Education KLAs…………………………………………….…………… 8 Enrich Learning Activities for Students…………….…........................... -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Introduction Multicultural Education Means Different Things to Different

Introduction Multicultural education means different things to different people. However, the differences are not as great, confusing, or contradictory as some critics and analysts claim. Many of these differences are more semantic than substantive, a reflection of the developmental level in the field and the disciplinary orientation of advocates. One should expect people who have been involved in a discipline or educational movement for a long time to understand and talk about it differently from those who are new to it. Similarly, educators who look at schooling from the vantage point of sociology, psychology, or economics will have differing views of the key concerns of schooling. Yet, these disparate analysts may agree on which issues are the most critical ones. Such differences over means coupled with widespread agreement on substance are naturally found in discussions of multicultural education. But this diversity should not be a problem, especially when we consider that multicultural education is all about plurality. The field includes educational scholars, researchers, and practitioners from a wide variety of personal, professional, philosophical, political, and pedagogical backgrounds. Therefore, we should expect that they will use different points of reference in discussing ethnic diversity and cultural pluralism. Yet, when allowances are made for these differences, a consensus on the substantive components of multicultural education quickly emerges. Such agreement is evident in areas such as the key content dimensions, value priorities, the justification for multicultural education, and its expected outcomes. Only when these fundamentals are articulated do variations emerge. Some advocates talk about expected outcomes, while others consider the major determining factor to be the group being studied; the arena of school action is the primary focus for one set of advocates, and still others are most concerned with distinctions between theory and practice. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Radio Television Hong Kong Performance Pledge 2015-16

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE 2015-16 This performance pledge summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Service Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public service broadcaster in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public service broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2015-16, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; and will receive advice from the Board of Advisors on issues pertaining to its terms of -

Radio Television Hong Kong

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE This leaflet summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public broadcaster in the HKSAR. Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2010-11, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; maximize return on government funding by further enhancing cost efficiency and productivity; continue to ensure staff handle public funds in a prudent and cost-effective manner; actively explore opportunities in generating revenue for the government from RTHK programmes and contents; provide media coverage and produce special radio, television programmes and related web content for Legislative Council By-Elections 2010, Shanghai Expo 2010, 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou and World Cup in South Africa; and carry out the preparatory work for launching the new digital audio broadcasting and digital terrestrial television services to achieve its mission as the public service broadcaster. -

Is Poverty Eradication Impossible? a Critique on the Misconceptions of the Hong Kong Government • Hung Wong

STARTING3 ISSUES FROM PER YEAR2016 The China Review An Interdisciplinary Journal on Greater China Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Special Issue Introduction: Poverty in a Rich Society—The Case of Hong Kong • Maggie Lau (Guest Editor) My Experience Researching Poverty over the Past 35 Years • Nelson W. S. Chow Poverty in Hong Kong • Maggie Lau, Christina Pantazis, David Gordon, Lea Lai, and Eileen Sutton Setting the Poverty Line: Policy Implications for Squaring the Welfare Circle in Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Hong Kong • Florence Meng-soi Fong and Chack-kie Wong Health Inequality in Hong Kong • Roger Y. Chung and Samuel Y. S. Wong An Interdisciplinary Enhancing Global Competitiveness and Human Capital Management: Does Journal on Education Help Reduce Inequality and Poverty in Hong Kong? • Ka Ho Mok Greater China Is Poverty Eradication Impossible? A Critique on the Misconceptions of the Hong Kong Government • Hung Wong Book Reviews Special Issue Poverty in a Rich Society Vol. 15, No. 2, Fall 2015 2, Fall 15, No. Vol. —The Case of Hong Kong Available online via ProQuest Asia Business & Reference Project MUSE at http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/china_review/ JSTOR at http://www.jstor.org/journal/chinareview STARTING3 ISSUES FROM PER YEAR2016 The China Review An Interdisciplinary Journal on Greater China Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Special Issue Introduction: Poverty in a Rich Society—The Case of Hong Kong • Maggie Lau (Guest Editor) My Experience Researching Poverty over the Past 35 Years • Nelson W. S. Chow Poverty in Hong Kong • Maggie Lau, Christina Pantazis, David Gordon, Lea Lai, and Eileen Sutton Setting the Poverty Line: Policy Implications for Squaring the Welfare Circle in Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Hong Kong • Florence Meng-soi Fong and Chack-kie Wong Health Inequality in Hong Kong • Roger Y. -

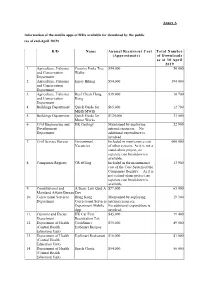

Information of the Mobile Apps of B/Ds Available for Download by the Public (As of End-April 2019)

Annex A Information of the mobile apps of B/Ds available for download by the public (as of end-April 2019) B/D Name Annual Recurrent Cost Total Number (Approximate) of Downloads as at 30 April 2019 1. Agriculture, Fisheries Country Parks Tree $54,000 50 000 and Conservation Walks Department 2. Agriculture, Fisheries Enjoy Hiking $54,000 394 000 and Conservation Department 3. Agriculture, Fisheries Reef Check Hong $39,000 10 700 and Conservation Kong Department 4. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $65,000 12 700 MBIS/MWIS 5. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $120,000 33 000 Minor Works 6. Civil Engineering and HK Geology Maintained by deploying 22 900 Development internal resources. No Department additional expenditure is involved. 7. Civil Service Bureau Government Included in maintenance cost 600 000 Vacancies of other systems. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 8. Companies Registry CR eFiling Included in the maintenance 13 900 cost of the Core System of the Companies Registry. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 9. Constitutional and A Basic Law Quiz A $77,000 65 000 Mainland Affairs Bureau Day 10. Correctional Services Hong Kong Maintained by deploying 19 300 Department Correctional Services internal resources. Department Mobile No additional expenditure is App involved. 11. Customs and Excise HK Car First $45,000 19 400 Department Registration Tax 12. Department of Health CookSmart: $35,000 49 000 (Central Health EatSmart Recipes Education Unit) 13. Department of Health EatSmart Restaurant $16,000 41 000 (Central Health Education Unit) 14. -

Building a New Music Curriculum: a Multi-Faceted Approach

Action, Criticism and Theory for Music Education The scholarly electronic journal of Volume 3, No. 2 July, 2004 Thomas A. Regleski, Editor Wayne Bowman, Associate Editor Darryl Coan, Publishing Editor Electronic Article Building a New Music Curriculum A Multi-faceted Approach Chi Cheung Leung © Leung, C. 2004, All rights reserved. The content of this article is the sole responsibility of the author. The ACT Journal, the MayDay Group, and their agents are not liable for any legal actions that may arise involving the article's content, including but not limited to, copyright infringement. ISSN 1545-4517 This article is part of an issue of our online journal: ACT Journal: http://act.maydaygroup.org MayDay Site: http://www.maydaygroup.org Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education Page 2 of 28 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Building a New Music Curriculum A Multifaceted Approach Chi Cheung Leung, The Hong Kong Institute of Education Introduction This paper addresses one of the four questions of the MayDay Group Action Ideal No. 7 (see http://www.nyu.edu/education/music/mayday/maydaygroup/index.htm): To what extent and how can music education curriculums take broader educational and social concerns into account? A multifaceted music curriculum model (MMC Model)—one that addresses relevant issues, criteria, and parameters typically involved or often overlooked—is proposed for consideration in designing a music curriculum. This MMC Model and the follow up discussion are based on the results of a larger study entitled The role of Chinese music in secondary school education in Hong Kong (Leung, 2003a; referred to here as the “original study”), and one of its established models, the Chinese Music Curriculum Model, which was developed in connection with research concerning curriculum decisions for the teaching of Chinese music.