Hong Kong's Post-Colonial Education Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045 (1988)

www.lawcommission.gov.np Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045 (1988) Date of Authentication and Publication 2045.7.28 (13 Nov. 1988) Amendments : 1. Technical Education and Vocational 2050.2.27(9 May 1993) Training Council Act, 2049 (1993) 2. Education and Sports Related Some Nepal 2063.9.14(8 Jan.2006) Acts (Amendment) Act, 2063 (2006)1 3. Republic Strengthening and Some Nepal 2066.10.7 (21 Jan. 2010) Laws Amendment Act, 2066 (2010)2 Act Number 20 of the Year 2045(1988) An Act Made to Provide for the Establishment and Provision of Technical Education and Vocational Training Preamble : Whereas, it is expedient to establish and provide for the Technical Education and Vocational Training Council in order to manage technical education and vocational training in a planned manner and to make determination and accreditation of standards of skills, for the generation of basic and medium level technical human resources; 1 This Act came into force on 17 Shrwan 2063(2 Aug. 2006). 2 This Act came into force on 15 Jestha 2065 (28 June 2008) and " Prasati " has been deleted. 1 www.lawcommission.gov.np www.lawcommission.gov.np Now, therefore, be it enacted by His Majesty King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, on the advice and with the consent of the Rastriya Panchayat . 1. Short title and commencement : 1.1 This Act may be called as the "Technical Education and Vocational Training Council Act, 2045(1989)". 1.2 This Act shall come into force on such a date as the Government of Nepal may appoint by publishing a Notification in the Nepal Gazette. -

Media Capture with Chinese Characteristics

JOU0010.1177/1464884917724632JournalismBelair-Gagnon et al. 724632research-article2017 Article Journalism 1 –17 Media capture with Chinese © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: characteristics: Changing sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917724632DOI: 10.1177/1464884917724632 patterns in Hong Kong’s journals.sagepub.com/home/jou news media system Nicholas Frisch Yale University, USA Valerie Belair-Gagnon University of Minnesota, USA Colin Agur University of Minnesota, USA Abstract In the Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong, a former British territory in southern China returned to the People’s Republic as a semi-autonomous enclave in 1997, media capture has distinct characteristics. On one hand, Hong Kong offers a case of media capture in an uncensored media sector and open market economy similar to those of Western industrialized democracies. Yet Hong Kong’s comparatively small size, close proximity, and broad economic exposure to the authoritarian markets and politics of neighboring Mainland China, which practices strict censorship, place unique pressures on Hong Kong’s nominally free press. Building on the literature on media and politics in Hong Kong post-handover and drawing on interviews with journalists in Hong Kong, this article examines the dynamics of media capture in Hong Kong. It highlights how corporate-owned legacy media outlets are increasingly deferential to the Beijing government’s news agenda, while social media is fostering alternative spaces for more skeptical and aggressive voices. This article develops a scholarly vocabulary to describe media capture from the perspective of local journalists and from the academic literature on media and power in Hong Kong and China since 1997. -

Promotion of STEM Education

Preamble Promotion of STEM Education This document entitled Promotion of STEM Education – Unleashing Potential in Innovation is issued to solicit views and comments from various stakeholders in the education and other sectors of the community on the recommendations and proposed strategies for the promotion of STEM education among schools in Hong Kong. It should be read in conjunction with the separate Briefs for Updating the Science, Technology and Mathematics Education Key Learning Area (KLA) Curricula). The recommendations and strategies proposed in this document on promoting STEM education have a direct bearing on school-based curriculum development over the next decade, and chart the way forward for sustaining the ongoing renewal of the school curriculum. Comments and suggestions on this document are welcome and should be sent to the following by 4 January 2016: Chief Curriculum Development Officer (Science) Education Bureau Room E232, 2/F, East Block Education Bureau Kowloon Tong Education Services Centre 19 Suffolk Road Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong (Fax: 2194 0670 ; E-mail: [email protected]) Curriculum Development Council November 2015 Contents Introduction 1 Why is it Necessary to Promote STEM Education? 2 What is the Direction for Promoting STEM Education? 3 Guiding Principles for Promoting STEM Education……………..…….. 3 Aim and objectives of Promoting STEM Education……..…….............. 4 What are the Recommendations for STEM Education in Hong Kong? 5 Strengthening the Ability to Integrate and Apply……………………….. 5 Approaches for Organising Learning Activities on STEM Education.… 6 Teacher Collaboration and Community Partnership……………......…... 7 What are the Strategies for Promoting STEM Education? 8 Renew the Curricula of Science, Technology and Mathematics Education KLAs…………………………………………….…………… 8 Enrich Learning Activities for Students…………….…........................... -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Radio Television Hong Kong Performance Pledge 2015-16

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE 2015-16 This performance pledge summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Service Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public service broadcaster in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public service broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2015-16, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; and will receive advice from the Board of Advisors on issues pertaining to its terms of -

Radio Television Hong Kong

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE This leaflet summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public broadcaster in the HKSAR. Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2010-11, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; maximize return on government funding by further enhancing cost efficiency and productivity; continue to ensure staff handle public funds in a prudent and cost-effective manner; actively explore opportunities in generating revenue for the government from RTHK programmes and contents; provide media coverage and produce special radio, television programmes and related web content for Legislative Council By-Elections 2010, Shanghai Expo 2010, 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou and World Cup in South Africa; and carry out the preparatory work for launching the new digital audio broadcasting and digital terrestrial television services to achieve its mission as the public service broadcaster. -

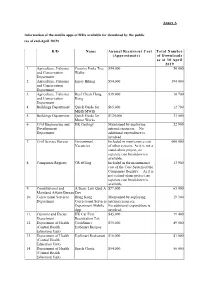

Information of the Mobile Apps of B/Ds Available for Download by the Public (As of End-April 2019)

Annex A Information of the mobile apps of B/Ds available for download by the public (as of end-April 2019) B/D Name Annual Recurrent Cost Total Number (Approximate) of Downloads as at 30 April 2019 1. Agriculture, Fisheries Country Parks Tree $54,000 50 000 and Conservation Walks Department 2. Agriculture, Fisheries Enjoy Hiking $54,000 394 000 and Conservation Department 3. Agriculture, Fisheries Reef Check Hong $39,000 10 700 and Conservation Kong Department 4. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $65,000 12 700 MBIS/MWIS 5. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $120,000 33 000 Minor Works 6. Civil Engineering and HK Geology Maintained by deploying 22 900 Development internal resources. No Department additional expenditure is involved. 7. Civil Service Bureau Government Included in maintenance cost 600 000 Vacancies of other systems. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 8. Companies Registry CR eFiling Included in the maintenance 13 900 cost of the Core System of the Companies Registry. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 9. Constitutional and A Basic Law Quiz A $77,000 65 000 Mainland Affairs Bureau Day 10. Correctional Services Hong Kong Maintained by deploying 19 300 Department Correctional Services internal resources. Department Mobile No additional expenditure is App involved. 11. Customs and Excise HK Car First $45,000 19 400 Department Registration Tax 12. Department of Health CookSmart: $35,000 49 000 (Central Health EatSmart Recipes Education Unit) 13. Department of Health EatSmart Restaurant $16,000 41 000 (Central Health Education Unit) 14. -

2019 JUPAS Admissions Scores of 9 JUPAS Participating-Institutions (Applicable to LOCAL JUPAS Applicants Only)

2019 JUPAS Admissions Scores of 9 JUPAS Participating-institutions (applicable to LOCAL JUPAS applicants only) ©JUPAS [2019] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including but not limited to photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means or on the internet or otherwise) without the prior written permission of JUPAS / JUPAS participating-institutions except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Ordinance. The information contained in the JUPAS website is solely owned by JUPAS. The JUPAS Office cautions members of the public that any such information reproduced in part or in whole in any format by parties other than JUPAS and without the prior knowledge or written consent of JUPAS may be incomplete, misleading, and / or inaccurate. JUPAS takes no responsibility for the unauthorised use of any of its information. Members of the public are advised to refer to the information contained in the JUPAS and 9 JUPAS participating-institutions' websites as the official source of Admissions Scores. The information contained here is extracted from the websites of the respective JUPAS participating-institutions and is applicable to LOCAL JUPAS APPLICANTS only. You are advised to consult the websites of the respective JUPAS participating-institutions for further and additional information. As not all programmes select students on the basis of HKDSE Examination levels / grades alone and the actual levels / grades of the students admitted to each programme may vary from year to year (depending on the overall levels / grades achieved by applicants in a particular year, the number of applicants applying to the programme, changes in selection criteria, etc.), information in this section is for reference only, and should not be used to predict the chance of admission to any programme in subsequent years. -

2015 JUPAS Admissions Scores of 9 JUPAS Participating-Institutions

2015 JUPAS Admissions Scores of 9 JUPAS Participating-institutions ©JUPAS [2015] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means or on the internet or otherwise) without the prior written permission of JUPAS / JUPAS participating-institutions except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Ordinance. The information contained in the JUPAS website is solely owned by JUPAS. The JUPAS Office cautions members of the public that any such information reproduced in part or in whole in any format by parties other than JUPAS and without the prior knowledge or written consent of JUPAS may be incomplete, misleading, and / or inaccurate. JUPAS takes no responsibility for the unauthorised use of any of its information. Members of the public are advised to refer to the information contained in the JUPAS and 9 JUPAS participating-institutions' websites as the official source of Admissions Scores. The information contained here is extracted from the websites of the respective JUPAS participating-institutions. You are advised to consult the websites of the respective JUPAS participating-institutions for further and additional information. As not all programmes select students on the basis of HKDSE Examination levels / grades alone and the actual levels / grades of the students admitted to each programme may vary from year to year (depending on the overall levels / grades achieved by applicants in a particular year, the number of applicants applying to the programme, changes in selection criteria, etc.), information in this section is for reference only, and should not be used to predict the chance of admission to any programme in subsequent years. -

Building a New Music Curriculum: a Multi-Faceted Approach

Action, Criticism and Theory for Music Education The scholarly electronic journal of Volume 3, No. 2 July, 2004 Thomas A. Regleski, Editor Wayne Bowman, Associate Editor Darryl Coan, Publishing Editor Electronic Article Building a New Music Curriculum A Multi-faceted Approach Chi Cheung Leung © Leung, C. 2004, All rights reserved. The content of this article is the sole responsibility of the author. The ACT Journal, the MayDay Group, and their agents are not liable for any legal actions that may arise involving the article's content, including but not limited to, copyright infringement. ISSN 1545-4517 This article is part of an issue of our online journal: ACT Journal: http://act.maydaygroup.org MayDay Site: http://www.maydaygroup.org Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education Page 2 of 28 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Building a New Music Curriculum A Multifaceted Approach Chi Cheung Leung, The Hong Kong Institute of Education Introduction This paper addresses one of the four questions of the MayDay Group Action Ideal No. 7 (see http://www.nyu.edu/education/music/mayday/maydaygroup/index.htm): To what extent and how can music education curriculums take broader educational and social concerns into account? A multifaceted music curriculum model (MMC Model)—one that addresses relevant issues, criteria, and parameters typically involved or often overlooked—is proposed for consideration in designing a music curriculum. This MMC Model and the follow up discussion are based on the results of a larger study entitled The role of Chinese music in secondary school education in Hong Kong (Leung, 2003a; referred to here as the “original study”), and one of its established models, the Chinese Music Curriculum Model, which was developed in connection with research concerning curriculum decisions for the teaching of Chinese music. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 782 SO 007 248 AUTHOR Pyykkonen, Maija-Liisa, Ed. TITLE About the Finnish Educational System. Information

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 782 SO 007 248 AUTHOR Pyykkonen, Maija-Liisa, Ed. TITLE About the Finnish Educational System. Information Bulletin. INSTITUTION Finnish National Board of Education, Helsinki. Research and Development Bureau. PUB DATE Mar 73 NOTE 23p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 DESCRIPTORS *Comparative Education; *Educational Change; Educational Planning; Elementary Education; *Grade Organization; *Instructional Program Divisions; National Programs; Organization; *Organizational Change; Planning; Preschool Education; School Organization; School Planning; Secondary Education; Social Change; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS *Finland; Nationwide Planning ABSTRACT This Information Bulletin discusses the general reform of the Finnish education system, necessitated by events of the sixties, which included a larger number of students leaving the Primary Schools after grade four to enter the secondary level, the failure of Primary Schools to meet demands of basic education, and the closing of rural Primary Schools concommitant with the need for new urban Primary Schools in response to changes in population patterns. The old system consisted of eight years of compulsory schooling, beginning at the age of seven, divided into six years of Primary School and two to three years of Civic School, which specialized according to local needs and on the basis of general, vocational, and pre-orientational education. Secondary schools consisted of a five grade lover section, the Middle School, and a three grade upper section, the Gymnasium. The new system will include preschool education and a Comprehensive School covering the elementary years, replacing Primary, Civic, and Middle Schools. Teacher training also will be reformed, taking place at the University within education departments rather than in training schools.(JH) INFORMATION NATIONAL BOARD OF EDUCATION Research and Development Bureau Finland BULLETIN U S MENT OF HEALTH.