1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1) Meeting Your Bible 2) Discussing the Bible (Breakout Rooms for 10

Wednesday Wellspring: A Bible Study for UU’s (part 1) Bible Study 101: Valuable Information for Serious Students taught by Keith Atwater, American River College worksheet / discussion topics / study guide 1) Meeting Your Bible What is your Bible’s full title, publisher, & publication date? Where did you get your Bible? (source, price, etc.) What’s your Bible like? (leather cover, paperback, old, new, etc.) Any Gospels words in red? What translation is it? (King James, New American Standard, Living Bible, New International, etc.) Does your Bible include Apocrypha?( Ezra, Tobit, Maccabees, Baruch) Preface? Study Aids? What are most common names for God used in your edition? (Lord, Jehovah, Yahweh, God) The Bible in your hands, in book form, with book titles, chapter and verse numbers, page numbers, in a language you can read, at a reasonably affordable price, is a relatively recent development (starting @ 1600’s). A Bible with cross-references, study aids, footnotes, commentary, maps, etc. is probably less than 50 years old! Early Hebrew (Jewish) Bible ‘books’ (what Christians call the Old Testament) were on 20 - 30 foot long scrolls and lacked not only page numbers & chapter indications but also had no punctuation, vowels, and spaces between words! The most popular Hebrew (Jewish) Bible @ the time of Jesus was the “Septuagint” – a Greek translation. Remember Alexander the Great conquered the Middle East and elsewhere an “Hellenized’ the ‘Western world.’ 2) Discussing the Bible (breakout rooms for 10 minutes. Choose among these questions; each person shares 1. Okay one bullet point to be discussed, but please let everyone say something!) • What are your past experiences with the Bible? (e.g. -

The Documentary Hypothesis

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 12/1 (2001): 22Ð30. Article copyright © 2001 by Greg A. King. The Documentary Hypothesis Greg A. King Pacific Union College How did the Pentateuch or Torah come to be written?1 What process was in- volved in its composition?2 That is, did the author simply receive visions and write out word for word exactly what he or she3 had heard and seen in vision? Did he make use of written sources? Did he incorporate oral traditions? Who was the principal author anyway? Do these questions really matter? If so, why? While many average church members consider Moses the author of the first five books of the Bible, most biblical scholars of the last century have maintained that questions related to the composition of the Pentateuch are best answered by referring to the documentary hypothesis. This is the popular label for the theory of pentateuchal authorship and composition that has dominated most liberal biblical scholarship for the past century. In fact, so thoroughly has it dominated the field that some scholars simply assume it to be correct and feel no need to offer evidence to support it.4 This in spite of the fact that recently penetrating critiques from both 1The term Pentateuch refers to the first five books of the Bible and is a transliteration of a Greek term meaning Òfive scrolls.Ó The term Torah, though it has other meanings also, is sometimes used to denote the same five books and is a transliteration of a Hebrew word meaning Òinstruction.Ó See the discussion of these terms in Barry Bandstra, Reading the Old Testament (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1995), 24. -

The Documentary Hypothesis

THE PENTATEUCH in the battle for I So, thirdly, Israel must keep the covenant announced publicly to the whole nation, for the ; with a series of wholeheartedly. 'Love the LORD your God with Lord's appearance on the mountain was too ter s and how the all your heart and with all your soul and with all rifying. Instead they were made known to rng the secular your strength' (6:5) sums up the whole message Moses alone (Ex. 20: 19-21; Dt. 5:5), who then Levi (chs. 34 I of Moses. This meant keeping the Ten Com passed them on to the people. o the establish mandments given by God at Sinai (ch. 5). It Moses' role as a mediator is stressed those guilty of meant applying the Commandments to every throughout the Pentateuch. Time and again ~ I i sphere of life. The second and longest sermon laws are introduced by the statement, 'Then the land was more Ile land in which of Moses consists of a historical retrospect LORD said to Moses'. This implies a special in vas therefore, a followed by an expansion and application of the timacy with God, suggesting that if God is the Jfe: especially of commandments to every sphere of Israel's life ultimate source of the law, Moses was its chan . (ch. 35).It was, in Canaan; the laws in chs. 12 - 25 roughly nel, if not the human author of it. This impres for ever, and the follow the order of the commandments and ex sion is reinforced most strongly by the book of :signed to ensure pand and comment on them. -

The Miracle at the Sea Remarks on the Recent Discussion About Origin and Composition of the Exodus Narrative

The Miracle at the Sea Remarks on the Recent Discussion about Origin and Composition of the Exodus Narrative Jan Christian Gertz* 1 Introduction: The Exodus Narrative and the Debate about the Formation of the Pentateuch The story of the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt in Exod 1–15 “constitutes the point of crystallization of the great Pentateuchal narrative in its entirety.”1 It is, therefore, hardly surprising that the Exodus narrative plays an important role and often served as a paradigm in the recent debate about the formation of the Pentateuch.2 As a result there is much controversy about these chapters in pentateuchal scholarship. The classic formulation of the New Documentary Hypothesis assumes a Yahwistic, Elohistic, and Priestly source in Exod 1–15, as well as several pre- and post-priestly additions that were joined in successive stages. If we survey the commentaries and monographs of recent years, we find copious refutations and modifications of this model.3 By name but hardly with regard to approach, * My sincere thanks to my colleague Anselm C. Hagedorn for the translation of this article. The research was done while I was part of the group “Convergence and Divergence in Pentateuchal Theory” at the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies in Jerusalem and supported by the eurias Fellowship Programme. 1 Martin Noth, A History of Pentateuchal Traditions (trans. with an introduction by Bernhard W. Anderson; Chico, Calif.: Scholar Press, 1981), 51; trans. of Überlieferungsgeschichte des Pentateuch (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1948), 54. 2 Cf. inter alia Marc Vervenne, “Current Tendencies and Developments in the Study of the Book of Exodus,” in The Book of Exodus (ed. -

GENESIS in the PENTATEUCH Konrad Schmid I in the Heyday of the Documentary Hypothesis It Was a Common Assumption That Most Texts

GENESIS IN THE PENTATEUCH Konrad Schmid Introduction In the heyday of the Documentary Hypothesis it was a common assumption that most texts in Genesis were to be interpreted as elements of narra- tive threads that extended beyond the book of Genesis and at least had a pentateuchal or hexateuchal scope (J, E, and P). To a certain degree, exe- gesis of the book of Genesis was therefore tantamount to exegesis of the book of Genesis in the Pentateuch or Hexateuch. The Theologische Realen- zyklopädie, one of the major lexica in the German-speaking realm, has for example no entry for “Genesis” but only for the “Pentateuch” and its alleged sources. At the same time, it was also recognized that the material—oral or written—which was processed and reworked by the authors of the sources J, E, and P originated within a more modest narrative perspective that was limited to the single stories or story cycles, a view emphasized especially by Julius Wellhausen, Hermann Gunkel, Kurt Galling, and Martin Noth:1 J and E were not authors, but collectors.2 Gunkel even went a step further: “‘J’ and ‘E’ are not individual writers, but schools of narrators.”3 But with the successful reception of Gerhard von Rad’s 1938 hypothesis of a tradi- tional matrix now accessible through the “historical creeds” like Deut 26:5– 9, which was assumed to have also been the intellectual background of the older oral material, biblical scholarship began to lose sight of the view taken by Wellhausen, Gunkel, Galling, and Noth. In addition, von Rad saw J and 1 Julius Wellhausen, Die Composition des Hexateuchs und der historischen Bücher des Alten Testaments (3rd ed.; Berlin: Reimer, 1899); Hermann Gunkel, Genesis (6th ed.; HKAT 1/1; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1964 [repr. -

A Farewell to the Yahwist? the Composition of the Pentateuch In

A FAREWELL TO THE YAHWIST? The Composition of the Pentateuch in Recent European Interpretation Edited by Thomas B. Dozeman and Konrad Schmid Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta CONTENTS Abbreviations ...............................................................................................vii Introduction Thomas B. Dozeman and Konrad Schmid..................................................1 Part 1: Main Papers The Elusive Yahwist: A Short History of Research Thomas Christian Römer ..........................................................................9 The So-Called Yahwist and the Literary Gap between Genesis and Exodus Konrad Schmid .......................................................................................29 The Jacob Story and the Beginning of the Formation of the Pentateuch Albert de Pury ........................................................................................51 The Transition between the Books of Genesis and Exodus Jan Christian Gertz ................................................................................73 The Literary Connection between the Books of Genesis and Exodus and the End of the Book of Joshua Erhard Blum ..........................................................................................89 The Commission of Moses and the Book of Genesis Thomas B. Dozeman ............................................................................107 Part 2: Responses The Yahwist and the Redactional Link between Genesis and Exodus Christoph Levin ....................................................................................131 -

The Documentary Hypothesis © כל הזכויות שמורות

© כל הזכויות שמורות The Documentary Hypothesis © כל הזכויות שמורות Contemporary Jewish Thought from Shalem Press: Essential Essays on Judaism Eliezer Berkovits God, Man and History Eliezer Berkovits The Dawn: Political Teachings of the Book of Esther Yoram Hazony Moses as Political Leader Aaron Wildavsky © כל הזכויות שמורות The Documentary Hypothesis and the composition of the pentateuch Eight Lectures by Umberto Cassuto With an introduction by Joshua A. Berman Translated from the Hebrew by Israel Abrahams Shalem Press Jerusalem and New York © כל הזכויות שמורות Umberto Cassuto (1883–1951) held the chair of Bible studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His books include A Commentary on the Book of Genesis, A Commentary on the Book of Exodus, and a treatise on Ugaritic literature entitled The Goddess Anath. Shalem Press, 13 Yehoshua Bin-Nun Street, Jerusalem Copyright © 2006 by the Shalem Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Originally published in Hebrew as Torath HaTeudoth by Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1941 First English edition 1961 Cover design: Erica Halivni Cover picture: Copyright J.L. de Zorzi/visualisrael/Corbis ISBN 978-965-7052-35-8 Printed in Israel ∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the -

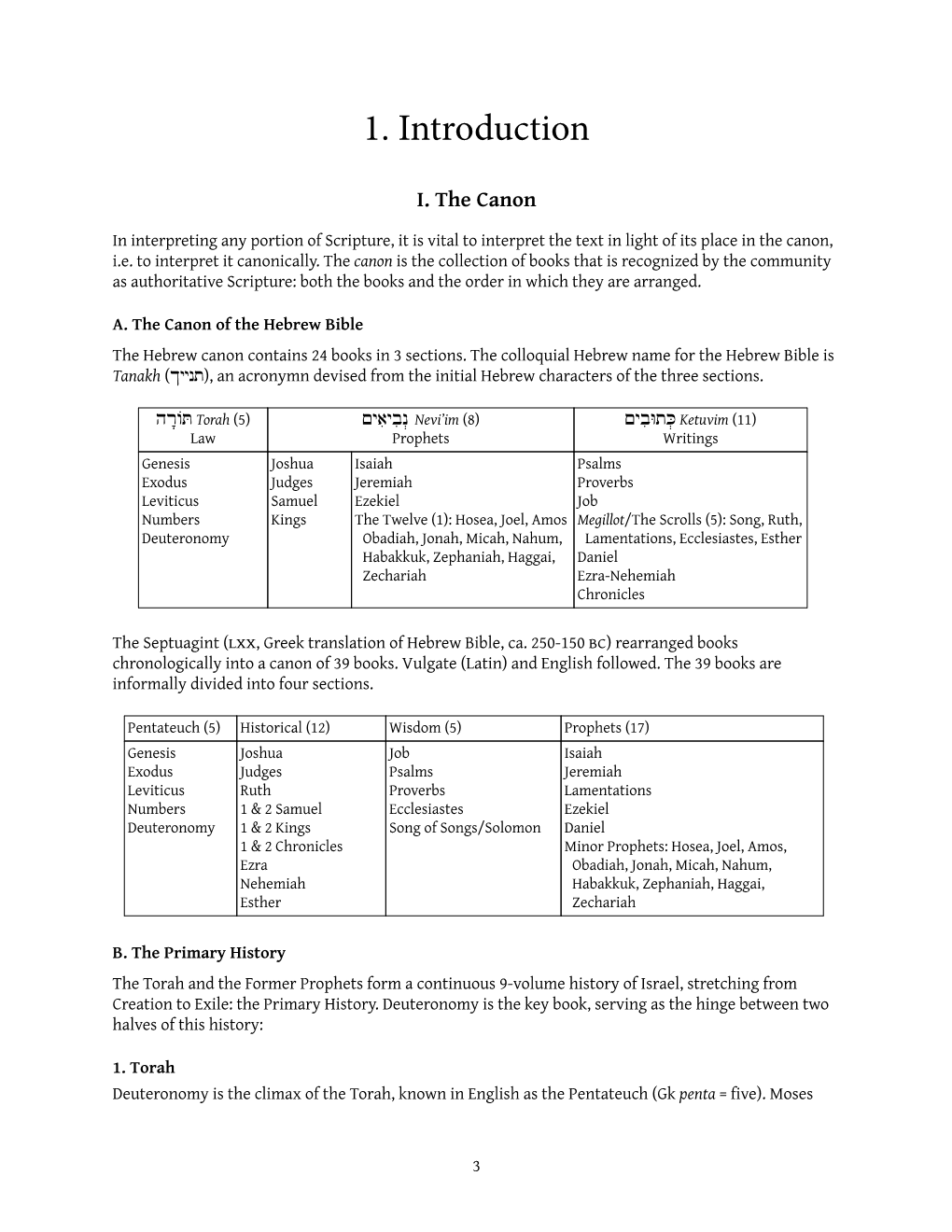

Studying the Bible: the Tanakh and Early Christian Writings

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2019 Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein Kansas State University Anna Goins Kansas State University Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Biblical Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Eiselein, Gregory; Goins, Anna; and Wood, Naomi J., "Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings" (2019). NPP eBooks. 29. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Copyright © 2019 Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood New Prairie Press, Kansas State University Libraries Manhattan, Kansas Cover design by Anna Goins Cover image by congerdesign, CC0 https://pixabay.com/photos/book-read-bible-study-notes-write-1156001/ Electronic edition available online at: http://newprairiepress.org/ebooks This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International (CC-BY NC 4.0) License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Publication of Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings was funded in part by the Kansas State University Open/Alternative Textbook Initiative, which is supported through Student Centered Tuition Enhancement Funds and K-State Libraries. -

Documentary Hypothesis

Documentary Hypothesis Notes from: 1. JOHN BARTON, "Source Criticism," The Anchor Bible Dictionary [http://www.ucalgary.ca/~eslinger/genrels/DocHypothesis.html] 2. http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/rs/2/Judaism/jepd.html 3. http:// www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Documentary_hypothesis.doc "SOURCE CRITICISM. [VI, 162] Formerly called “literary criticism” or “higher criticism,” source criticism is a method of biblical study, which analyzes texts that are not the work of a single author but result from the combination of originally separate documents. This method has been applied to texts of the Old Testament (especially but not exclusively the Pentateuch) and New Testament (especially but not exclusively the gospels). This entry surveys the application of this method to those texts. A. Definitions Modern literary conventions forbid plagiarism, and require authors to identify and acknowledge any material they have borrowed from another writer. But in ancient times it was common to “write” a book by transcribing existing material, adapting and adding to it from other documents as required, and not indicating which parts were original and which borrowed. The OT contains few books, which are the work of a single author throughout; for the most part its books are composite, and in some cases the source materials are drawn from original documents that may be spread over several centuries. Source criticism seeks to separate out these originally independent documents, and to assign them to relative (and, if possible, absolute) dates. Source criticism is to be distinguished from other critical methods. Where original documents prove not to have been free compositions, but to rest on older, oral tradition, FORM CRITICISM may then be used to penetrate behind the written text. -

The Old Testament, Second Edition Michael D. Coogan Glossary of Terms

The Old Testament, Second Edition Michael D. Coogan Glossary of terms acrostic A text in which the opening letters of successive lines form a word, phrase, or pattern. The acrostics in the Bible are poems in which the first letters of successive lines or stanzas are the letters of the Hebrew alphabet in order. Ammonites Israel’s neighbors east of the Jordan River. The Ammonites are the “sons of Ammon,” who according to Genesis 19 were the offspring of Lot by one of his daughters. Their name is preserved in the modern city of Amman, Jordan. angel A word of Greek origin originally meaning messenger. In the Bible, these are supernatural beings sent by God to humans. anthropomorphic (anthropomorphism) The attribution of human characteristics to a nonhuman being, usually a deity. apocalyptic A genre of literature in which details concerning the end-time are revealed by a heavenly messenger or angel. Apocrypha Jewish religious writings of the Hellenistic and Roman periods that are not considered part of the Bible by Jews and Protestants, but are part of the canons of Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches, who also call them the deuterocanonical books. apodictic law A type of law characterized by absolute or general commands or prohibitions, as in the Ten Commandments. It is often contrasted with casuistic law. Aramaic A language originating in ancient Syria that in the second half of the first millennium BCE became used widely throughout the Near East. Parts of the books of Daniel and Ezra are written in Aramaic. ark of the covenant The religious symbol of the premonarchic confederation of the twelve tribes of Israel, later installed in the Temple in Jerusalem by Solomon in the tenth century BCE. -

Read Review in the Review of Biblical Literature

RBL 10/2009 Hupping, Carol, ed. The Jewish Bible: A JPS Guide Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2008. Pp. x + 291. Paper. $22.00. ISBN 0827608519. Gilbert Lozano Mennonite School of Theology Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil This book is part of the Jewish Publication Society’s JPS Guides Series, whose aim is to provide introductions to topics of interest within Jewish studies. The book uses the designation “The Bible” to refer to the Hebrew canon: the Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim. The book appears to have a double aim. First, it sets out to be “an introduction and compact reference” (vii) while at the same time aiming to be “based on scholarship without being ‘scholarly’ ” (vii). To that effect, the book contains articles contributed by a first-rate coterie of Jewish scholars. Most of the articles essays to have been written specifically for this book, though several were extracted from other sources and are used here for their relevance. It is primarily oriented to an educated public, though not necessarily an academic one. It is also aimed at a Jewish audience—perhaps for introductory courses in Jewish studies at colleges and universities and even synagogues. But it could also prove to be a good introduction to the Hebrew Bible for a larger audience, especially for those desiring to be familiarized with how Jews view and interpret their Scriptures. The book’s organization follows both a topical and canonical approach. It devotes seven chapters to introductory topics. The first three chapters cover introductory aspects aptly described by their titles: “What is the Bible?”; “How the Bible Became ‘The Bible’ ”; and This review was published by RBL 2009 by the Society of Biblical Literature. -

Why the Documentary Hypothesis Is the Frankenstein of Biblical Studies Duane Garrett

The Undead Hypothesis: Why the Documentary Hypothesis is the Frankenstein of Biblical Studies Duane Garrett Duane Garrett is a professor of Old A stock feature of the classic “grade B” established result of biblical scholarship Testament at Gordon Conwell Theologi- horror movie is the undead creature who in universities and theological schools cal Seminary. He has served the Inter- relentlessly stalks innocent people and around the world. Books and mono- national Mission Board by teaching in terrorizes an otherwise quiet village. graphs rooted in it still frequently appear. Southern Baptist seminaries in both Whether it be Frankenstein, the Mummy, Laughably, some of these books are Korea and Canada. Dr. Garrett is the Dracula, or simply crude, grotesque zom- touted for their “startling new interpre- author of many articles and books, bies with rotting flesh falling off their tations” of the history of the Bible while including two Old Testament commen- limbs and faces, these villains share a in fact doing little more than repackaging taries in the New American Commen- common trait. They all have already died old ideas.1 If the sheer volume of litera- tary series. He is currently working on a and usually have already been buried. But ture on a hypothesis were a demonstra- commentary on the Song of Solomon then, either through the blunder of some tion of its veracity, the documentary for the Word Biblical Commentary investigator or the work of some evil hypothesis would indeed be well estab- series. genius, they rise and walk again. The lished.2 Nevertheless, while the dead dilemma posed by these undead mon- hand of the documentary hypothesis still sters is obvious: How do you kill some- dominates Old Testament scholarship as one who is already dead? its official orthodoxy, the cutting edge A similar creature stalks the halls of research of recent years has typically been biblical studies.