The Formation of the Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1) Meeting Your Bible 2) Discussing the Bible (Breakout Rooms for 10

Wednesday Wellspring: A Bible Study for UU’s (part 1) Bible Study 101: Valuable Information for Serious Students taught by Keith Atwater, American River College worksheet / discussion topics / study guide 1) Meeting Your Bible What is your Bible’s full title, publisher, & publication date? Where did you get your Bible? (source, price, etc.) What’s your Bible like? (leather cover, paperback, old, new, etc.) Any Gospels words in red? What translation is it? (King James, New American Standard, Living Bible, New International, etc.) Does your Bible include Apocrypha?( Ezra, Tobit, Maccabees, Baruch) Preface? Study Aids? What are most common names for God used in your edition? (Lord, Jehovah, Yahweh, God) The Bible in your hands, in book form, with book titles, chapter and verse numbers, page numbers, in a language you can read, at a reasonably affordable price, is a relatively recent development (starting @ 1600’s). A Bible with cross-references, study aids, footnotes, commentary, maps, etc. is probably less than 50 years old! Early Hebrew (Jewish) Bible ‘books’ (what Christians call the Old Testament) were on 20 - 30 foot long scrolls and lacked not only page numbers & chapter indications but also had no punctuation, vowels, and spaces between words! The most popular Hebrew (Jewish) Bible @ the time of Jesus was the “Septuagint” – a Greek translation. Remember Alexander the Great conquered the Middle East and elsewhere an “Hellenized’ the ‘Western world.’ 2) Discussing the Bible (breakout rooms for 10 minutes. Choose among these questions; each person shares 1. Okay one bullet point to be discussed, but please let everyone say something!) • What are your past experiences with the Bible? (e.g. -

(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

1 “Do not bare your heads and do not rend your clothes” (Leviticus 10:6): On Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible Yael Shemesh, Bar Ilan University Many agree today that objective research devoid of a personal dimension is a chimera. As noted by Fewell (1987:77), the very choice of a research topic is influenced by subjective factors. Until October 2008, mourning in the Bible and the ways in which people deal with bereavement had never been one of my particular fields of interest and my various plans for scholarly research did not include that topic. Then, on October 4, 2008, the Sabbath of Penitence (the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement), my beloved father succumbed to cancer. When we returned home after the funeral, close family friends brought us the first meal that we mourners ate in our new status, in accordance with Jewish custom, as my mother, my three brothers, my father’s sisters, and I began “sitting shivah”—observing the week of mourning and receiving the comforters who visited my parent’s house. The shivah for my father’s death was abbreviated to only three full days, rather than the customary week, also in keeping with custom, because Yom Kippur, which fell only four days after my father’s death, truncated the initial period of mourning. Before my bereavement I had always imagined that sitting shivah and conversing with those who came to console me, when I was so deep in my grief, would be more than I could bear emotionally and thought that I would prefer for people to leave me alone, alone with my pain. -

Genesis, Book of 2. E

II • 933 GENESIS, BOOK OF Pharaoh's infatuation with Sarai, the defeat of the four Genesis 2:4a in the Greek translation: "This is the book of kings and the promise of descendants. There are a num the origins (geneseos) of heaven and earth." The book is ber of events which are added to, or more detailed than, called Genesis in the Septuagint, whence the name came the biblical version: Abram's dream, predicting how Sarai into the Vulgate and eventually into modern usage. In will save his life (and in which he and his wife are symbol Jewish tradition the first word of the book serves as its ized by a cedar and a palm tree); a visit by three Egyptians name, thus the book is called BeriPSit. The origin of the (one named Hirkanos) to Abram and their subsequent name is easier to ascertain than most other aspects of the report of Sarai's beauty to Pharaoh; an account of Abram's book, which will be treated under the following headings: prayer, the affliction of the Egyptians, and their subse quent healing; and a description of the land to be inher A. Text ited by Abram's descendants. Stylistically, the Apocryphon B. Sources may be described as a pseudepigraphon, since events are l. J related in the first person with the patriarchs Lamech, 2. E Noah and Abram in turn acting as narrator, though from 3. p 22.18 (MT 14:21) to the end of the published text (22.34) 4. The Promises Writer the narrative is in the third person. -

Torah: Covenant and Constitution

Judaism Torah: Covenant and Constitution Torah: Covenant and Constitution Summary: The Torah, the central Jewish scripture, provides Judaism with its history, theology, and a framework for ethics and practice. Torah technically refers to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). However, it colloquially refers to all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh. Torah is the one Hebrew word that may provide the best lens into the Jewish tradition. Meaning literally “instruction” or “guidebook,” the Torah is the central text of Judaism. It refers specifically to the first five books of the Bible called the Pentateuch, traditionally thought to be penned by the early Hebrew prophet Moses. More generally, however, torah (no capitalization) is often used to refer to all of Jewish sacred literature, learning, and law. It is the Jewish way. According to the Jewish rabbinic tradition, the Torah is God’s blueprint for the creation of the universe. As such, all knowledge and wisdom is contained within it. One need only “turn it and turn it,” as the rabbis say in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) 5:25, to reveal its unending truth. Another classical rabbinic image of the Torah, taken from the Book of Proverbs 3:18, is that of a nourishing “tree of life,” a support and a salve to those who hold fast to it. Others speak of Torah as the expression of the covenant (brit) given by God to the Jewish people. Practically, Torah is the constitution of the Jewish people, the historical record of origins and the basic legal document passed down from the ancient Israelites to the present day. -

Dead Sea Scrolls Deciphered: Esoteric Code Reveals Ancient Priestly Calendar 21 February 2018, by Charlotte Hempel

Dead Sea Scrolls deciphered: esoteric code reveals ancient priestly calendar 21 February 2018, by Charlotte Hempel here. These fragments, at most, contain parts of three words and often fewer. The text contains parts of a calendar based on a 364-day solar year, which has the benefit of the annual festivals never falling on a Saturday, which would have clashed with the Jewish Sabbath. This calendar is promoted in a number of Dead Sea Scrolls and was probably used instead of the more widespread approximately 354-day lunar calendar. The Hebrew Bible does not present a clear and complete calendar, which is why ancient Jewish groups debated the issue. The Babylonian calendar was luni-solar comprising 12 lunar months. But the Puzzle: fragments of 2,000-year-old scrolls before Dead Sea Scrolls also provide evidence of a reassembly. Credit: Shay Halevi, Israel Antiquities number of texts that attempt to incorporate both the Authority, The Leon Levy Library of the Dead Sea movements of the sun and the moon into more Scrolls complex calendars. About 1,000 Dead Sea Scrolls discovered just over 70 years ago near Khirbet Qumran on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea have been officially published since the turn of the millennium. But in the case of some, all that was left were poorly preserved remains of texts written in a What the scroll ‘puzzle’ looks like when assembled. Credit: University of Haifa, Shay Halevi, Israel Antiquities cryptic script – and all that had been released to Authority, The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital the world were photos of small pieces of Library manuscript, in a preliminary order. -

Reading the Old Testament History Again... and Again

Reading the Old Testament History Again... and Again 2011 Ryan Center Conference Taylor Worley, PhD Assistant Professor of Christian Thought & Tradition 1 Why re-read OT history? 2 Why re-read OT history? There’s so much more to discover there. It’s the key to reading the New Testament better. There’s transformation to pursue. 3 In both the domains of nature and faith, you will find the most excellent things are the deepest hidden. Erasmus, The Sages, 1515 4 “Then he said to them, “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.’” Luke 24:44 5 God wishes to move the will rather than the mind. Perfect clarity would help the mind and harm the will. Humble their pride. Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 1669 6 Familiar Approaches: Humanize the story to moralize the characters. Analyze the story to principalize the result. Allegorize the story to abstract its meaning. 7 Genesis 22: A Case Study 8 After these things God tested Abraham and said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here am I.” 2 He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” “By myself I have sworn, declares the Lord, because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, 17 I will surely bless you, and I will surely multiply your offspring as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore. -

Jesus and the Gospel in the Old Testament Edited By

“Our hope and prayer is that these expositions will prove not only clarifying but humbling, enriching, and edifying, as well as incentives to keep preaching and teaching Old Testament texts.” D. A. Carson THE BIBLE’S STORY LINE IS GRAND IN ITS SWEEP, beautiful in its form, and unified in its message. However, many of us still struggle both to understand and to best communicate how the Old and New Testaments fit together, especially in relation to the person and work of Jesus Christ. Eight prominent evangelical pastors and scholars demonstrate what it looks like to preach Christ from the Old Testament in this collection of expositions of various Old Testament texts: ALBERT MOHLER — Studying the Scriptures and Finding Jesus (John 5:31–47) TIM KELLER — Getting Out (Exodus 14) ALISTAIR BEGG — From a Foreigner to King Jesus (Ruth) JAMES MACDONALD — When You Don’t Know What to Do (Psalm 25) CONRAD MBEWE — The Righteous Branch (Jeremiah 23:1–8) MATT CHANDLER — Youth (Ecclesiastes 11:9–12:8) MIKE BULLMORE — God’s Great Heart of Love toward His Own (Zephaniah) D. A. CARSON — Getting Excited about Melchizedek (Psalm 110) From the experience of the Israelites during the exodus, to the cryptic words about Melchizedek in the Psalms, here are 8 helpful examples of successful approaches to preaching the gospel from the Old Testament by some of the most skilled expositors of our day. Jesus and the Gospel in the D. A. Carson (PhD, Cambridge University) is research professor of New old testament Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, where he has taught since 1978. -

Exodus in the Dead Sea Scrolls

Exodus in the Dead Sea Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford The book of Exodus is a very important text among the Dead Sea Scrolls, especially in the collection found in the eleven caves in the vicinity of Khirbet Qumran (“the Qumran collection”). Because of the variety of texts and the fragmentary nature of the manuscripts, each text (or group of texts) will be treated individually. At the end of this essay, I will draw some conclusions concerning the status and use of Exodus in the Qumran collection. 1 Exodus Manuscripts Eighteen fragmentary manuscripts of the book of Exodus itself were found in caves 1, 2, and 4 at Qumran.1 The oldest, 4QExod-Levf, dates paleographi- cally to c. 250bce, while the latest, 4QExodk, dates between 30–135ce.2 The eighteen manuscripts between them cover parts of all the chapters of Exodus, beginning with 1:1–6 (4QExodb, 4QpaleoGen-Exodl) and ending with 40:8–27 1 D. Barthélemy, “Exode,” in Qumran Cave i (ed. D. Barthélemy and J.T. Milik; djd 1; Oxford: Clarendon, 1955), 50–51; M. Baillet, “Exode (i),” in Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumran (ed. M. Bail- let, J.T. Milik, R. de Vaux; djd 3; Oxford: Clarendon, 1962), 49–52; M. Baillet, “Exode (ii),” in Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumran (ed. M. Baillet, J.T. Milik, and R. de Vaux; djd 3; Oxford: Claren- don, 1962), 52–55; M. Baillet, “Exode (iii),” in Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumran (ed. M. Baillet, J.T. Milik, and R. de Vaux; djd 3; Oxford: Clarendon, 1962), 56; James R. -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 79:3–4 July/October 2015 Table of Contents The Lutheran Hymnal after Seventy-Five Years: Its Role in the Shaping of Lutheran Service Book Paul J. Grime ..................................................................................... 195 Ascending to God: The Cosmology of Worship in the Old Testament Jeffrey H. Pulse ................................................................................. 221 Matthew as the Foundation for the New Testament Canon David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 233 Luke’s Canonical Criterion Arthur A. Just Jr. ............................................................................... 245 The Role of the Book of Acts in the Recognition of the New Testament Canon Peter J. Scaer ...................................................................................... 261 The Relevance of the Homologoumena and Antilegomena Distinction for the New Testament Canon Today: Revelation as a Test Case Charles A. Gieschen ......................................................................... 279 Taking War Captive: A Recommendation of Daniel Bell’s Just War as Christian Discipleship Joel P. Meyer ...................................................................................... 301 Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage: The Triumph of Culture? Gifford A. Grobien ............................................................................ 315 Pastoral Care and Sex Harold L. Senkbeil ............................................................................. -

The Proximity of the Pre-Samaritan Qumran Scrolls to the Sp*

chapter 27 The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Dead Sea Scrolls: The Proximity of the Pre-Samaritan Qumran Scrolls to the sp* The study of the Samaritans and the scrolls converge at several points, definitely with regard to the biblical scrolls, but also regarding several nonbiblical scrolls. Recognizing the similarities between the sp and several Qumran biblical scrolls, some scholars suggested that these scrolls, found at Qumran, were actu- ally Samaritan. This assumption implies that these scrolls were copied within the Samaritan community, and somehow found their way to Qumran. If cor- rect, this view would have major implications for historical studies, and for the understanding of the Qumran and Samaritan communities. This view could imply that Samaritans lived or visited at Qumran, or that the Qumran commu- nity received Samaritan documents, but other scenarios are possible as well. A rather extreme suggestion, proposed by Thord and Maria Thordson, would be that the inhabitants of Qumran were not Jewish, but Samaritan Essenes who fled to Qumran after the destruction of the Samaritan Temple by John Hyrcanus in 128 bce.1 Although this view is not espoused by many scholars, it needs to be taken seriously. The major proponent of the theory that Samaritan scrolls were found at Qumran was M. Baillet in a detailed study of the readings of the sp agreeing with the Qumran texts known until 1971.2 Baillet provided no specific arguments for this view other than the assumption of a close rela- tion between the Essenes and the Samaritans suggested by J. Bowman3 and * I devote this paper to the two areas that were in the center of Alan Crown’s scholarly interests, the Samaritans and the Scrolls, in that sequence. -

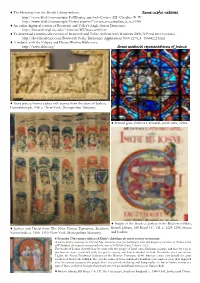

Some Useful Websites Some Medieval Representations of Joshua Some

♦ The Hexateuch on the British Library website: Some useful websites http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Cotton_MS_Claudius_B_IV http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=cotton_ms_claudius_b_iv_f140v ♦ An online digitized version of Bosworth and Toller’s Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: http://beowulf.engl.uky.edu/~kiernan/BT/bosworth.htm ♦ To download a multimedia version of Bosworth and Toller (will run with Windows 2000/XP and later versions) http://download.cnet.com/Bosworth-Toller-Dictionary-Application/3000-2279_4 -10668222.html ♦ A website with the Vulgate and Douay-Rheims Bible texts: http://www.drbo.org/ Some medieval representations of Joshua ♦ Ivory plaque from a casket with scenes from the story of Joshua, Constantinople, 10th c. (New York, Metropolitan Museum) ♦ Stained glass, Poitiers Cathedral, north nave, 1240s ♦ Incipit of the Book of Joshua in the Rochester Bible, ♦ Joshua and David from The Nine Heroes Tapestries, Southern British Library, MS Royal 1 C. VII, c. 1225-1250, Moses Netherlands, c. 1400–1410 (New York, Metropolitan Museum) and Joshua. ♦ From the 17thcentury edition of Ælfric’s Libellum de vetero et novo testamento . A Saxon Treatise concerning the Old and New Testament, Now first published in print with English of our times, by William L’Isle of Wilburgham, the original remaining still to be seene in Sir Robert Cottons Librarie , 1623. The booke of Ioshua sheweth how he went with the people of Israel vnto Abrahams country, and how he won it; and how the sunne stood still, while hee got the victory, and how he diuided the land. This booke also I turned into English for Prince Ethelwerd [ ealdorman of the Western Provinces, †998], wherein a man may behold the great wonders of God really fulfilled. -

Church Holy Books 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament

Church Holy Books •How many books does the Church use? •What are they for and when are they used? 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament 39 Books: Books of the LAW (5): – Genesis – Exodus – Leviticus – Numbers – Deuteronomy 1 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Historical Books (12): – Joshua – Judges – Ruth – 1 & 2 Samuel – 1 & 2 Kings – 1 & 2 Chronicles – Ezra – Nehemiah – Esther 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Poetic Books (5): – Job – Psalms – Proverbs – Ecclesiastes – Song of Songs 2 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Major Prophets (5): – Isaiah – Jeremiah – Lamentations of Jeremiah – Ezekiel – Daniel 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Minor Prophets (12): Hosea Nahum Joel Habakkuk Amos Zephaniah Obadiah Haggai Jonah Zechariah Micah Malachi 3 1. Holy Bible “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16) Most important of all books All the other books are based upon It and inspired by It Our Church is an entirely Biblical Church relying on God’s inspired Word for our spiritual nourishment 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Easy way to remember: – 5 – 12 – 5 – 5 – 12 – Law (5) – Historical (12) – Poetic (5) – Major Prophets (5) – Minor Prophets (12) 4 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament More Old Testament Books Deuterocanonical Books 10 additional books or parts of books were removed from the Protestant translation of the Bible, but exist in the Hebrew, Septuagint (Greek) and Vulgate (Latin) 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament According to the Coptic tradition, they are: – Tobit – Judith – 1 and 2 Maccabees – Wisdom – Sirach – Baruch – Rest of Esther – Additions to Daniel – Psalm 151 5 1.