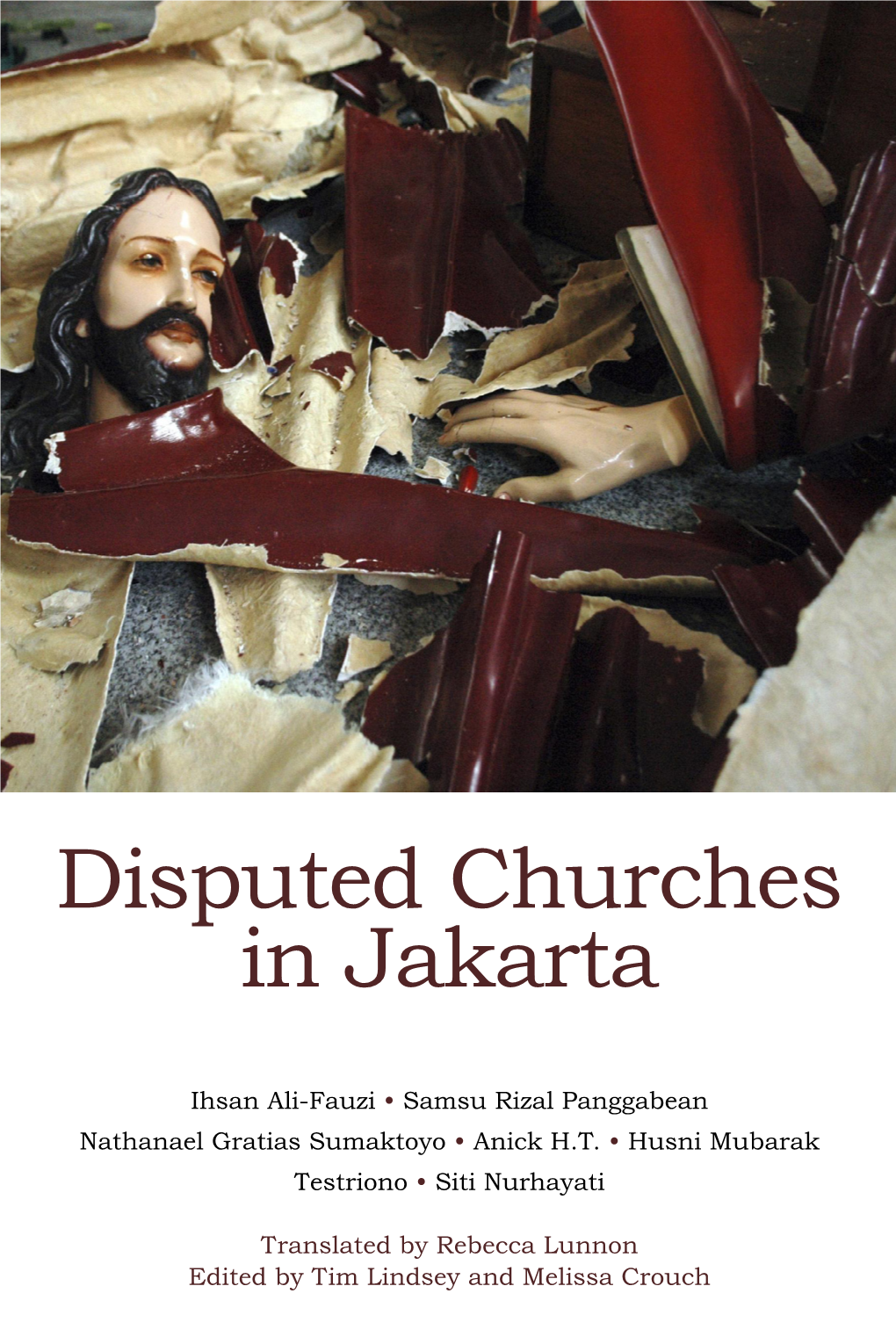

Disputed Churches in Jakarta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 Cakung Polder

Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report – phase 2 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized December 2014 FHM – Technical review and support Jakarta Flood Management System Including Sunter, Cakung, Marunda and upper Cideng Ciliwung diversions and Cisadane Technical review and support Jakarta Flood Management System Final Report - phase 2 © Deltares, 2014 December 2014, Final Report - Phase 2 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Introduction to the project 2 1.3 Polder systems 2 1.4 Project Tasks 4 1.5 Report outline 5 2 Kamal / Tanjungan polder 7 2.1 Description of the area 7 2.2 Pump scheme alternatives 8 2.2.1 A1 – Kamal and Tanjungan as separate systems, no additional storage 9 2.2.2 A2 – Combined Kamal and Tanjungan system, storage reservoir 45 ha 12 2.2.3 A3 – Kamal-Tanjungan with 90 ha storage 14 2.3 Verification with the hydraulic model and JEDI Synchronization 15 2.3.1 Introduction 15 2.3.2 Results 16 2.3.3 Impact of creation of western lake NCICD 18 2.4 Synchronization with other hydraulic infrastructure 19 3 Lower Angke / Karang polder 20 3.1 Description of the area 20 3.2 Pump scheme alternatives 21 3.2.1 B1 – Lower Angke/Karang, no additional storage 22 3.2.2 B2A – Lower Angke/Karang, new reservoir at Lower Angke 23 3.2.3 B2B – Lower Angke/Karang, 30 ha waduk and 12 ha emergency storage 25 3.2.4 B3 – as B2B, but with all possible green area as emergency storage 27 3.2.5 B4 –Splitting the polder in two parts, no additional storage 29 3.2.6 B5 –Splitting the polder area -

38 BAB III DESKRIPSI WILAYAH A. Tinjaun Umum Kondisi Kota

BAB III DESKRIPSI WILAYAH A. Tinjaun Umum Kondisi Kota Administrasi Jakarta Timur Pemerintah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Timur merupakan salah satu wilayah administrasi di bawah Pemerintah Provinsi DKI Jakarta. Wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Timur. Pemerintahan Kota Administrasi Jakarta Timur dibagi ke dalam 10 Kecamatan, yaitu Kecamatan Pasar Rebo, Ciracas, Cipayung, Makasar, Kramatjati, Jatinegara, Duren Sawit, Cakung, Pulogadung dan Matraman. Wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Timur memiliki perbatasan sebelah utara dengan Kota Administrasi Jakarta Utara dan Jakarta Pusat, sebelah timur dengan Kota Bekasi (Provinsi Jawa Barat), sebelah selatan Kabupaten Bogor (Provinsi Jawa Barat) dan sebelah barat dengan Kota Administrasi Jakarta Selatan. B. Kondisi Geografis Kota administrasi Jakarta Timur merupakan bagian dari wilayah provinsi DKI Jakarta yang terletak antara 106º49ʾ35ˮ Bujur Timur dan 06˚10ʾ37ˮ Lintang Selatan, dengan memiliki luas wilayah 187,75 Km², batas wilayah sebagai berikut : 1. Utara : Kotamadya Jakarta Utara dan Jakarta Pusat 2. Timur : Kotyamada Bekasi (Provinsi Jawa Barat) 3. Selatan : Kabupaten Bogor (Provinsi Jawa Barat) 4. Barat : Kotyamada Jakarta Selatan 38 PETA ADMINISTRATIF KOTA JAKARTA TIMUR Sumber : Jakarta Timur dalam angka,2015 Kampung Pulo bertempat di Kecamatan Jatinegara, Kelurahan Kampung Melayu, Jakarta Timur. Nama Kampung Pulo berasal dari bentuk dataran ini ketika air sungai Ciliwung meningkat ada yang berbentuk pulau kecil. Dataran Kampung Pulo cukup rendah dari jalan raya Jatinegara Barat. Kampung Pulo merupakan kawasan permukiman yang padat dan berdiri di tanah negara. Penduduk yang tinggal didalamnya rata – rata berpenghasilan rendah, sehingga kualitas lingkungan semakin menurun. Saat ini semua kawasan hunian dituntut untuk menjadi hunian yang berkelanjutan, dengan luas area ± 8 Ha (sebagian besar berbatasan dengan sungai Ciliwung) dan kondisi fisik Kampung Pulo-Jakarta Timur saat ini maka pemukiman 39 tersebut tidak dapat bersifat berkelanjutan. -

Change Detection of Land Cover at Flood Potential Areas Using Multitemporal Image Data in East Jakarta City

Published by : International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) http://www.ijert.org ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 9 Issue 07, July-2020 Change Detection of Land Cover at Flood Potential Areas using Multitemporal Image Data in East Jakarta City Abdul Wahid Hasyim Dimas Danur Cahya Ismu Rini Dwi Ari Department of Regional and Urban Department of Regional and Urban Department of Regional and Urban Planning, Universitas Brawijaya, Jl. Planning, Universitas Brawjaya, Jl. Planning, Universitas Brawijaya, Jl. MT. Haryono 167, Malang City, MT. Haryono 167, Malang City, MT. Haryono 167, Malang City, East Java, Indonesia, 65145 East Java, Indonesia, 65145 East Java, Indonesia, 65145 Abstract— East Jakarta City is one of 6 cities / regencies in well as the volume of water displaced due to the inability of the. The city of East Jakarta as one of the cities in the Special the absorption of water into the ground [3]. Capital Province of Jakarta has a significant growing population. Changing of land cover might result on flood The East Jakarta is the 1st city with the highest disaster disaster in related with the growth of population. Main purpose risk index value and the 2nd city with the highest flood of the study is to determine variable that influence the flood disaster risk index value in DKI Jakarta Province [4]. Jakarta height of an area with imagery data in the period of four has experienced many severe river flood events due to heavy decades – 1990, 2000, 2020, and 2020. The first step uses land rains, especially in 1996, 2002, 2007, 2013 and 2014 [5]. -

Nama Sekolah Jumlah Anak Penerima KJP SDN ANCOL 01 PG. 323 SDN ANCOL 03 PG. 210 SDN ANCOL 04 PT. 163 SDN ANGKE 01 PG. 375 SDN AN

Nama Sekolah Jumlah Anak Penerima KJP SD SDN ANCOL 01 PG. 323 SDN ANCOL 03 PG. 210 SDN ANCOL 04 PT. 163 SDN ANGKE 01 PG. 375 SDN ANGKE 03 PG. 72 SDN ANGKE 04 PT. 134 SDN ANGKE 05 PG. 79 SDN ANGKE 06 PG. 238 SDN BALE KAMBANG 01 PG. 138 SDN BALE KAMBANG 03 PG. 171 SDN BALIMESTER 01 PG. 69 SDN BALIMESTER 02 PT. 218 SDN BALIMESTER 03 PT. 274 SDN BALIMESTER 06 PG. 65 SDN BALIMESTER 07 PT. 110 SDN BAMBU APUS 01 PG. 84 SDN BAMBU APUS 02 PG. 92 SDN BAMBU APUS 03 PG. 283 SDN BAMBU APUS 04 PG. 79 SDN BAMBU APUS 05 PG. 89 SDN BANGKA 01 PG. 95 SDN BANGKA 03 PG. 96 SDN BANGKA 05 PG. 60 SDN BANGKA 06 PG. 42 SDN BANGKA 07 PG. 103 SDN BARU 01 PG. 10 SDN BARU 02 PG. 46 SDN BARU 03 PG. 124 SDN BARU 05 PG. 128 SDN BARU 06 PG. 107 SDN BARU 07 PG. 20 SDN BARU 08 PG. 163 SDN BATU AMPAR 01 PG. 24 SDN BATU AMPAR 02 PG. 100 SDN BATU AMPAR 03 PG. 81 SDN BATU AMPAR 05 PG. 61 SDN BATU AMPAR 06 PG. 113 SDN BATU AMPAR 07 PG. 108 SDN BATU AMPAR 08 PG. 66 SDN BATU AMPAR 09 PG. 95 SDN BATU AMPAR 10 PG. 111 SDN BATU AMPAR 11 PG. 91 SDN BATU AMPAR 12 PG. 64 SDN BATU AMPAR 13 PG. 38 SDN BENDUNGAN HILIR 01 PG. 144 SDN BENDUNGAN HILIR 02 PT. 92 SDN BENDUNGAN HILIR 03 PG. -

Jumlah Puskesmas Menurut Kabupaten/Kota (Keadaan 31 Desember 2013)

JUMLAH PUSKESMAS MENURUT KABUPATEN/KOTA (KEADAAN 31 DESEMBER 2013) PROVINSI DKI JAKARTA KODE KAB/KOTA RAWAT INAP NON RAWAT INAP JUMLAH 3101 KAB. ADM. KEPULAUAN SERIBU 1 7 8 3171 KOTA ADM. JAKARTA SELATAN 8 70 78 3172 KOTA ADM. JAKARTA TIMUR 5 83 88 3173 KOTA ADM. JAKARTA PUSAT 3 39 42 3174 KOTA ADM. JAKARTA BARAT 8 67 75 3175 KOTA ADM. JAKARTA UTARA 5 44 49 JUMLAH 30 310 340 P JENIS O WILAYAH KERJA KODE PUSKESMAS NO PROVINSI KABUPATEN/KOTA NAMA PUSKESMAS ALAMAT PUSKESMAS N PUSKESMAS Rawat Non Rawat Luas Jumlah E Desa D Inap Inap Wilayah Penduduk KEC. KEP. SERIBU 2.459 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101010201 SELATAN Dermaga Pulau Tidung, Kec. Kep. Seribu Selatan V 0 1 2.460 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101010202 KEL. PULAU TIDUNG Dermaga Pulau Tidung, Kec. Kep. Seribu Selatan 0 1 2.461 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101010203 KEL. P. UNTUNG JAWA Bogenville, Kec. Kep. Seribu Selatan 0 1 2.462 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101010204 KEL. PULAU PARI Pulau Lancang, Kec. Kep. Seribu Selatan 0 1 2.463 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101020102 KEL. PULAU KELAPA Kel. Pulau Kelapa, Kec. Kep. Seribu Utara 1 0 KEC. KEP. SERIBU 2.464 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101020201 UTARA/RB Dermaga Pulau Kelapa, Kec. Kep. Seribu Utara 0 1 2.465 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101020203 KEL. PULAU PANGGANG Kel. Pulau Panggang, Kec. Kep. Seribu Utara 0 1 2.466 DKI Jakarta Kab. Kep. Seribu P3101020204 KEL. PULAU HARAPAN Kel. Pulau Harapan, Kec. Kep. -

Kode Dan Data Wilayah Administrasi Pemerintahan Provinsi Dki Jakarta

KODE DAN DATA WILAYAH ADMINISTRASI PEMERINTAHAN PROVINSI DKI JAKARTA JUMLAH N A M A / J U M L A H LUAS JUMLAH NAMA PROVINSI / K O D E WILAYAH PENDUDUK K E T E R A N G A N (Jiwa) **) KABUPATEN / KOTA KAB KOTA KECAMATAN KELURAHAN D E S A (Km2) 31 DKI JAKARTA 31.01 1 KAB. ADM. KEP. SERIBU 2 6 - 10,18 21.018 31.01.01 1 Kepulauan Seribu 3 - Utara 31.01.01.1001 1 Pulau Panggang 31.01.01.1002 2 Pulau Kelapa 31.01.01.1003 3 Pulau Harapan 31.01.02 2 Kepulauan Seribu 3 - Selatan. 31.01.02.1001 1 Pulau Tidung 31.01.02.1002 2 Pulau Pari 31.01.02.1003 3 Pulau Untung Jawa 31.71 2 KODYA JAKARTA PUSAT 8 44 - 52,38 792.407 31.71.01 1 Gambir 6 - 31.71.01.1001 1 Gambir 31.71.01.1002 2 Cideng 31.71.01.1003 3 Petojo Utara 31.71.01.1004 4 Petojo Selatan 31.71.01.1005 5 Kebon Pala 31.71.01.1006 6 Duri Pulo 31.71.02 2 Sawah Besar 5 - 31.71.02.1001 1 Pasar Baru 31.71.02.1002 2 Karang Anyar 31.71.02.1003 3 Kartini 31.71.02.1004 4 Gunung Sahari Utara 31.71.02.1005 5 Mangga Dua Selatan 31.71.03 3 Kemayoran 8 - 31.71.03.1001 1 Kemayoran 31.71.03.1002 2 Kebon Kosong 31.71.03.1003 3 Harapan Mulia 31.71.03.1004 4 Serdang 1 N A M A / J U M L A H LUAS JUMLAH NAMA PROVINSI / JUMLAH WILAYAH PENDUDUK K E T E R A N G A N K O D E KABUPATEN / KOTA KAB KOTA KECAMATAN KELURAHAN D E S A (Km2) (Jiwa) **) 31.71.03.1005 5 Gunung Sahari Selatan 31.71.03.1006 6 Cempaka Baru 31.71.03.1007 7 Sumur Batu 31.71.03.1008 8 Utan Panjang 31.71.04 4 Senen 6 - 31.71.04.1001 1 Senen 31.71.04.1002 2 Kenari 31.71.04.1003 3 Paseban 31.71.04.1004 4 Kramat 31.71.04.1005 5 Kwitang 31.71.04.1006 6 Bungur -

Jakarta Metropolitan Region Policy Analysis

URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND SPATIAL PLANNING OF GREATER JAKARTA Wilmar Salim Forum Komunikasi Pembangunan – 18 March 2013 Objectives To provide a comprehensive overview of past and present spatial planning and urban development in the Jakarta Metropolitan Region (JMR) To provide summary of spatial planning and urban development activities in the JMR To follow the continuing decentralization of population out of DKI into the surrounding suburbs To give examples of how urban planning is not followed by its implementation Methods JMR planning: overview of 1965-1990 and 1990- 2012 plans discussion of spatial structure Population density analysis by subdistrict, year 2000 and 2010, with maps and gradient Employment density analysis, only year 2000 available at subdistrict level Urban development 2000-2010, with maps Jabotabek’s Dynamic Development – Henderson, Kuncoro, and Nasution (1996) Rapidly changing allocation of residences and business, following expected development patterns, 1980s to 1990s High population density: lower density in the core, densification of periphery and urban sprawl in the fringe Urban development hindered by poor land market institutions (weakly defined property rights, lack of active land use planning, low infrastructure investment) Manufacturing industrialization on Botabek with low land price and wages Multi-centered development: loss of monocentricity in Jakarta, increased concentration outside Jakarta Hurting small scale industry Spatial mismatch: low income workers’ residences separated from workplaces -

Floods in North Sumatera, West Java, Bengkulu and DKI Jakarta Provinces

Information bulletin Indonesia: Floods in North Sumatera, West Java, Bengkulu and DKI Jakarta provinces Glide n° FL-2019-000182-IDN Date of issue: 2 January 2020 Date of disaster: 28 December 2019 – now Point of contact: Arifin M. Hadi, PMI Head of Disaster Management Heather Fehr, IFRC Disaster Risk Management Delegate Operation start date: 28 December 2019 Category of disaster: Yellow Host National Society: Indonesian Red Cross (Palang Merah Indonesia) Number of people affected: approximately Number of people to be assisted: TBC (assessment is 10,000,000 affected, 31,232 IDP and 16 deaths ongoing) This bulletin is issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at this time. The Indonesian Red Cross – Palang Merah Indonesia (PMI), with the support of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), are continuing to monitor and respond to the situation with local and national resources. If required, additional financial resources will be sought via the relevant IFRC international disaster response mechanism. The situation Torrential rainfall from Tuesday, 31 December 2019, until Wednesday, 1 January 2020 morning triggered floods in Jakarta (all five municipalities: North, West, East, Central and South), West Java (districts of West Bandung, Karawang, Bogor, Bekasi and Bekasi City) and Banten Province (district of Lebak, South Tangerang, and Tangerang City). The Indonesian National Board for Disaster Management, locally known as Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana (BNPB), reported that the flooding spots has reached 268, while in Jakarta alone 158 flooding spots are identified. The most affected area in Jakarta is East Jakarta with 65 flood spots. -

FLOODS FL-2007-000023-IDN 5 February 2007 the Federation’S Mission Is to Improve the Lives of Vulnerable People by Mobilizing the Power of Humanity

Information Bulletin no. 01/2007 Glide no: INDONESIA: FLOODS FL-2007-000023-IDN 5 February 2007 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. In Brief This Bulletin is being issued for information only, and reflects the situation and the information available at this time. The Federation is not seeking funding or other assistance from donors for this operation at this time. For further information specifically related to this operation please contact: • Indonesian Red Cross (PMI): Mr. Arifin M. Hadi (acting head of disaster management division); mobile: +62.811.943.952; telephone: +62.21.799.2325 ext. 222; email: [email protected] • Federation country delegation in Indonesia: Bob McKerrow (head of delegation); email: [email protected]; mobile: +62.81.182.4859, phone: +62.21.7919.1841 (ext. 107); fax: +62.21.7918.0905 • Federation secretariat in Geneva (Asia Pacific department): Josse Gillijns (regional officer); email: [email protected] ; phone: +44.22.730.4224, fax: +41.22 733.0395 or Priya Nair; email: [email protected] ; phone: + 44-22.730.4296. The Situation Heavy rains since the 1 February 2007 have caused massive flooding in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta. According to the Indonesian Red Cross (PMI), floods have killed at least seven people and made nearly 270,000 people homeless. It is estimated that nearly 60% of the city is now inundated with water following days of torrential rains which have caused rivers to burst, pouring muddy waters up to 4 m deep into homes and buildings. -

Data Dasar Puskesmas Kondisi 31 Desember 2018

Data Dasar Puskesmas Kondisi 31 Desember 2018 PROVINSI DKI JAKARTA KEMENTERIAN KESEHATAN 2019 DATA DASAR PUSKESMAS PROVINSI DKI JAKARTA KONDISI DESEMBER 2018 KEMENTERIAN KESEHATAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA JAKARTA, 2019 ABSENSI PENGUMPULAN DATA DASAR PUSKESMAS 2018 MELALUI APLIKASI KOMDAT SAMPAI DENGAN 31 AGUSTUS 2019 Total PKM 31 Des No Provinsi Jumlah Kabupaten Total PKM Terisi % 2018 1 Aceh 23 348 270 77,59 2 Sumatera Utara 33 581 463 79,69 3 Sumatera Barat 19 275 272 98,91 4 Riau 12 216 216 100,00 5 Jambi 11 195 195 100,00 6 Sumatera Selatan 17 332 324 97,59 7 Bengkulu 10 180 179 99,44 8 Lampung 15 302 274 90,73 9 Kepulauan Bangka Belitung 7 64 64 100,00 10 Kepulauan Riau 7 83 83 100,00 11 DKI Jakarta 6 321 314 97,82 12 Jawa Barat 27 1069 552 51,64 13 Jawa Tengah 35 881 870 98,75 14 DI Yogyakarta 5 121 69 57,02 15 Jawa Timur 38 967 964 100,00 16 Banten 8 242 104 42,98 17 Bali 9 120 117 97,50 18 Nusa Tenggara Barat 10 166 166 100,00 19 Nusa Tenggara Timur 22 381 126 33,07 20 Kalimantan Barat 14 244 244 100,00 21 Kalimantan Tengah 14 200 81 40,50 22 Kalimantan Selatan 13 233 232 99,57 23 Kalimantan Timur 10 183 183 100,00 24 Kalimantan Utara 5 56 28 50,00 25 Sulawesi Utara 15 193 185 95,85 26 Sulawesi Tengah 13 202 192 95,05 27 Sulawesi Selatan 24 458 329 71,83 28 Sulawesi Tenggara 17 284 278 97,89 29 Gorontalo 6 93 72 77,42 30 Sulawesi Barat 6 94 47 50,00 31 Maluku 11 208 96 46,15 32 Maluku Utara 10 134 95 70,90 33 Papua Barat 13 159 159 100,00 34 Papua 29 408 209 51,23 Total 514 9993 8052 81,44 *Kab/Kota Terlampir |Data Dasar Puskesmas|i JUMLAH PUSKESMAS MENURUT KABUPATEN/KOTA (KEADAAN 31 DESEMBER 2018) PROVINSI DKI JAKARTA KODE KAB/KOTA NON RAWAT INAP RAWAT INAP JUMLAH 3101 KAB. -

9 Potential Roles of Biotic Factors in Regulating

Jurnal Ilmu dan Teknologi Kelautan Tropis, Vol. 4, No. 1, Hlm. 9-23, Juni 2012 POTENTIAL ROLES OF BIOTIC FACTORS IN REGULATING ZOOPLANKTON COMMUNITY DYNAMICS IN JAKARTA BAY SHALLOW WATER COASTAL ECOSYSTEM Arief Rachman1 and Nurul Fitriya1 1Research Center for Oceanography Indonesian Institute of Sciences Jl. Pasir Putih I, Ancol Timur , Jakarta Utara 14430 [email protected] ABSTRACT The dynamics in zooplankton abundance were regulated by changes in water physical-chemical parameters and interaction with biotic factors. In this research we examined the relationship between zooplankton community dynamic and important biotic factors, such as predation and food availability, in Jakarta bay. Plankton samplings were done in 10 sampling stations in Jakarta bay, from July to November 2009. Zooplankton samples were collected using horizontal towing method with NORPAC plankton net (mesh size 300 µm). Salinity, water depth, water temperature, and water transparency were measured. Phytoplankton samples were also collected with the same method as zooplankton, using Kitahara plankton net (mesh size 80 µm). Zooplankton taxas were grouped into two groups, the prey and predatory zooplankton. The results showed that there were two different patterns in zooplankton groups dynamic i.e., the single and double peak. The abundance peak in most zooplankton groups, such as copepods, cirripeds, luciferids, and tunicates, were induced by the high food availability during the phytoplankton bloom in August. The high abundance of prey zooplankton groups in August was responded by the predatory zooplankton groups, resulting in high abundance of predatory zooplankton in adjacent month. The high abundance of ctenophores and chordates (fish larvae) were suggested as the main factor for the low abundance of other zooplankton in September. -

32004 3174051005 1 Kelurahan 20200917 195236.Pdf

1 HALAMAN PENGESAHAN LAPORAN KKN Tema KKN : Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Kota Jakarta Timur dan Jakarta Selatan Bertajuk Edukasi Tanggap Covid-19 Ketua Kelompok : Pradipta Vidha Nararya NIM : 8111417238 Jurusan/Fakultas : Ilmu Hukum/Fakultas Hukum Jumlah Anggota : 32 Orang Lokasi KKN : 1. Kelurahan Baru Kecamatan Pasar Rebo Jakarta Timur 2. Kelurahan Cijantung Kecamatan Pasar Rebo Jakarta Timur 4. Kelurahan Gedong Kecamatan Pasar Rebo Jakarta Timur 3. Kelurahan Susukan Kecamatan Ciracas Jakarta Timur 4. Kelurahan Cibubur Kecamatan Ciracas Jakarta Timur 5. Kelurahan Rambutan Kecamatan Ciracas Jakarta Timur 6. Kelurahan Cililitan Kecamatan Kramatjati Jakarta Timur 7. Kelurahan Kampung Tengah Kecamatan Kramatjati Jakarta Timur 8. Kelurahan Pulogebang Kecamatan Cakung Jakarta Timur 9. Kelurahan Rawa Terate Kecamatan Cakung Jakarta Timur 10. Kelurahan Bidaracina Kecamatan Jatinegara Jakarta Timur 11. Kelurahan Jatinegara Kaum Kecamatan Pulo Gadung Jakarta Timur 2 12. Kelurahan Cipinang Besar Utara Kecamatan Jatinegara Jakarta Timur 13. Kelurahan Cipinang Besar Selatan Kecamatan Jatinegara Jakarta Timur 14. Kelurahan Rawa Bunga Kecamatan Jatinegara Jakarta Timur 15. Kelurahan Tanjung Barat Kecamatan Jagakarsa Jakarta Selatan 16. Kelurahan Jatipadang Kecamatan Pasar Minggu Jakarta Selatan 17. Kelurahan Pejaten Barat Kecamatan Pasar Minggu Jakarta Selatan 18. Kelurahan Mampang Prapatan Kecamatan Mampang Prapatan Jakarta Selatan 19. Kelurahan Pancoran Kecamatan Pancoran Jakarta Selatan 20. Kelurahan Cipete Selatan Kecamatan Cilandak Jakarta Selatan