Usage of Man-Made Underpass by Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

2.3 Nepal Road Network

2.3 Nepal Road Network Overview Primary Roads in Nepal Major Road Construction Projects Distance Matrix Road Security Weighbridges and Axle Load Limits Road Class and Surface Conditions Province 1 Province 2 Bagmati Province Gandaki Province Province 5 Karnali Province Sudurpashchim Province Overview Roads are the predominant mode of transport in Nepal. Road network of Nepal is categorized into the strategic road network (SRN), which comprises of highways and feeder roads, and the local road network (LRN), comprising of district roads and Urban roads. Nepal’s road network consists of about 64,500 km of roads. Of these, about 13,500 km belong to the SRN, the core network of national highways and feeder roads connecting district headquarters. (Picture : Nepal Road Standard 2070) The network density is low, at 14 kms per 100 km2 and 0.9 km per 1,000 people. 60% of the road network is concentrated in the lowland (Terai) areas. A Department of Roads (DoR’s) survey shows that 50% of the population of the hill areas still must walk two hours to reach an SRN road. Two of the 77 district headquarters, namely Humla, and Dolpa are yet to be connected to the SRN. Page 1 (Source: Sector Assessment [Summary]: Road Transport) Primary Roads in Nepal S. Rd. Name of Highway Length Node Feature Remarks N. Ref. (km) No. Start Point End Point 1 H01 Mahendra Highway 1027.67 Mechi Bridge, Jhapa Gadda chowki Border, East to West of Country Border Kanchanpur 2 H02 Tribhuvan Highway 159.66 Tribhuvan Statue, Sirsiya Bridge, Birgunj Connects biggest Customs to Capital Tripureshwor Border 3 H03 Arniko Highway 112.83 Maitighar Junction, KTM Friendship Bridge, Connects Chinese border to Capital Kodari Border 4 H04 Prithvi Highway 173.43 Naubise (TRP) Prithvi Chowk, Pokhara Connects Province 3 to Province 4 5 H05 Narayanghat - Mugling 36.16 Pulchowk, Naryanghat Mugling Naryanghat to Mugling Highway (PRM) 6 H06 Dhulikhel Sindhuli 198 Bhittamod border, Dhulikhel (ARM) 135.94 Km. -

Department of Roads

His Majesty’s Government of Nepal Ministry of Works and Transport Department of Roads Nov ‘99 Number 12 HMIS News Highway Management Information System, Planning Branch, DOR Traffic Database New Director General in DoR Maintenance and Rehabilitation Coordination Unit (MRCU) Mr. Ananda Prasad Khanal took charge as the Director General st has developed a database application for storing and processing of Department of Roads on 1 November 1999. Before that he traffic data obtained from Automatic Logger and Manual traffic was working as Deputy Director General, Planning Branch. count conducted every year by the Planning Branch. This database is useful in maintaining the data systematically. It Mr. Ananda Prasad Khanal did the Bachelor in Civil eliminates the tradition of keeping data in spreadsheet instead Engineering from Indian Institute of Technology (I.I.T) of in Access. This database is not the substitute of the software Bombay in 1968. He joined the Department of Roads in 1968 dROAD6 installed in the Highway Management Information and has been working since then. He had worked as assistant System (HMIS). engineer, divisional engineer, zonal engineer, Regional director, Project director of ADB Project Directorate Office The design of this database uses Microsoft Access 97 software and DDG of Planning Branch. He has visited several countries and incorporates Access 2000. Minimum hardware and has vast and diverse experience in the field of road requirements are a Pentium processor, 16Mb of Ram (32 MB construction, maintenance and planning. Preferred), and 1.5 MB of spare storage capacity. The database can be accessed through a straightforward menu system that is All the staffs of DoR congratulate him in his new appointment displayed in the following format. -

SAARC Regional Multimodal Transport Study

SAARC Regional Multimodal Transport Study SAARC REGIONAL MULTIMODAL TRANSPORT STUDY (SRMTS) Prepared for the SAARC Secretariat June 2006 i SAARC Regional Multimodal Transport Study © SAARC Secretariat No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without prior permission or due acknowledgement. Published by SAARC Secretariat P.O. Box: 4222 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: (977-1) 4221785, 4226350, 4231334 Fax: (977-1) 4227033, 4223991 Email: [email protected] Web-site: www.saarc-sec.org Printed by: WordScape, Nepal ii SAARC Regional Multimodal Transport Study PREFACE At the Twelfth SAARC Summit (Islamabad, 4-6 January 2004), the Heads of State or Government emphasized that for accelerated and balanced economic growth it is essential to strengthen transportation, transit and communication links across the region. Subsequently, SAARC Regional Multimodal Transport Study (SRMTS) has been conducted with a view to enhance transport connectivity among the Member States of SAARC to promote intra-regional trade and travel. SRMTS is a comprehensive Study covering all modes of transport - road, rail, maritime, aviation and inland waterways. The Report of the SRMTS has been appreciated by the higher SAARC bodies and its recommendations have now been prioritized. The SAARC Leaders have called for early implementation of the recommendations contained in the Study. I am also pleased to mention that action is being taken to extend SRMTS to include Afghanistan. I commend the national and regional consultants for conducting the Study successfully. I also wish to express my appreciation to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for providing technical and financial assistance (under ADB RETA 6187: Promoting South Asian Regional Economic Cooperation) in conducting the SRMTS. -

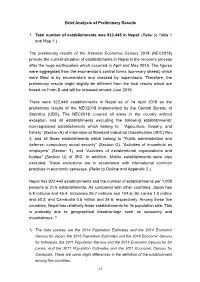

Brief Analysis of Preliminary Results

Brief Analysis of Preliminary Results 1. Total number of establishments was 922,445 in Nepal. (Refer to Table 1 and Map 1.) The preliminary results of the National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) provide the current situation of establishments in Nepal in the recovery process after the huge earthquakes which occurred in April and May 2015. The figures were aggregated from the enumerator’s control forms (summary sheets) which were filled in by enumerators and checked by supervisors. Therefore, the preliminary results might slightly be different from the final results which are based on Form B and will be released around June 2019. There were 922,445 establishments in Nepal as of 14 April 2018 as the preliminary results of the NEC2018 implemented by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). The NEC2018 covered all areas in the country without exception and all establishments excluding the following establishments: non-registered establishments which belong to “Agriculture, forestry, and fishery” (Section A) of International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) Rev. 4; and all those establishments which belong to “Public administration and defense; compulsory social security” (Section O), “Activities of household as employers” (Section T), and “Activities of extraterritorial organizations and bodies” (Section U) of ISIC. In addition, Mobile establishments were also excluded. These exclusions are in accordance with international common practices in economic censuses. (Refer to Outline and Appendix 2.) Nepal has 922,445 establishments and the number of establishments per 1,000 persons is 31.6 establishments. As compared with other countries, Japan has 5.8 millions and 45.4; Indonesia 26.7 millions and 104.6; Sri Lanka 1.0 million and 50.3; and Cambodia 0.5 million and 34.6; respectively. -

India's Connectivity with Its Himalayan Neighbours

PROXIMITY TO CONNECTIVITY: INDIA AND ITS EASTERN AND SOUTHEASTERN NEIGHBOURS PART 3 India’s Connectivity with its Himalayan Neighbours: Possibilities and Challenges Project Adviser: Rakhahari Chatterji Authors: Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury and Pratnashree Basu Research and Data Management: Sreeparna Banerjee and Mihir Bhonsale Observer Research Foundation, Kolkata © Observer Research Foundation 2017. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any part or by any means without the express written permission of ORF. India’s Connectivity with its Himalayan Neighbours: Possibilities and Challenges Observer Research Foundation Building Partnerships for a Global India Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a not-for-profit, multidisciplinary public policy think- tank engaged in developing and discussing policy alternatives on a wide range of issues of national and international significance. Some of ORF’s key areas of research include international relations, security affairs, politics and governance, resources management, and economy and development. ORF aims to influence formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India in a globalised world. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed and productive inputs, in-depth research, and stimulating discussions. Set up in 1990 during the troubled period of India’s transition from a protected economy to engaging with the international economic order, ORF examines critical policy problems facing the country and helps develop coherent policy responses in a rapidly changing global environment. As an independent think-tank, ORF develops and publishes informed and viable inputs for policy-makers in the government and for the political and business leadership of the country. It maintains a range of informal contacts with politicians, policy-makers, civil servants, business leaders and the media, in India and overseas. -

Journal-Of-Plant-Resources -2020.Pdf

Volume 18 Number 1 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Department of Plant Resources Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal 2020 ISSN 1995 - 8579 Journal of Plant Resources, Vol. 18, No. 1 JOURNAL OF PLANT RESOURCES Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Department of Plant Resources Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal 2020 Advisory Board Mr. Dhananjaya Paudyal Mr. Keshav Kumar Neupane Mr. Mohan Dev Joshi Managing Editor Mr. Tara Datt Bhat Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Dharma Raj Dangol Ms. Usha Tandukar Mr. Rakesh Kumar Tripathi Mr. Pramesh Bahadur Lakhey Ms. Nishanta Shrestha Ms. Pratiksha Shrestha Date of Online Publication: 2020 July Cover Photo: From top to clock wise direction. Inflorescence bearing multiple flowers in a cluster - Rhododendron cowanianum Davidian (PC: Pratikshya Chalise) Vanda cristata Wall. ex Lindl. (PC: Sangram Karki) Seedlings developed in half strength MS medium of Dendrobium crepidatum Lindl. & Paxton (PC: Prithivi Raj Gurung) Pycnoporus cinnabarinus (Jacq.: Fr.) Karst. (PC: Rajendra Acharya) Preparative HPLC (PC: Devi Prasad Bhandari) Flower head of Mimosa diplotricha C. Wright (PC: Lila Nath Sharma) © All rights reserved Department of Plant Resources (DPR) Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4251160, 4251161, 4268246, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Name of the author, year of publication. Title of the paper, J. Pl. Res. vol. 18, Issue 1 pages, Department of Plant Resources, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. ISSN: 1995-8579 Published By: Publicity and Documentation Section Department of Plant Resources (DPR), Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Reviewers: The issue can be retrieved from http://www.dpr.gov.np Prof. Dr.Anjana Singh Dr. Krishna Bhakta Maharjan Prof. Dr. Ram Kailash Prasad Yadav Dr. -

Preparatory Survey for Nagdhunga Tunnel Construction in Nepal

GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL MINISTRY OF PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT OF ROADS PREPARATORY SURVEY FOR NAGDHUNGA TUNNEL CONSTRUCTION IN NEPAL FINAL REPORT MARCH 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD TONICHI ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS, INC. METROPOLITAN EXPRESSWAY CO., LTD. 4R ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL, CO., LTD. JR (先) 15-012 EXCHANGE RATE September 2014 1NPR= 1.1 Japan Yen 1US$= 97.3 NPR 1US$= 107.1 Japan Yen LOCATION MAP 1 Local 2 3 Road H=1.5D~2.0D Image of East Side Tunnel Portal (KTM Side) Image of West Side Tunnel Portal (Naubise side) Start Point of Project (Houses Alongside) 7 4 6 8 5 9 4 2 1 Traffic congestion due to slow traffic 3 10 3 (Near sisnekhola) 5 6 7 1 Valley side slope that is deformed and dangerous Recent slope failure near objective road Traffic congestion due to stranded vehicles (Mal-functioning of trucks is frequent) 8 9 10 1 Traffics (Trucks) are frequently found stuck in Traffic congestion is frequent on objective road East side of the Project section is newly and densly open drainage section (high percentage of heavy vehicles) built-up area ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AADT Annual Average Daily Traffic ADB Asean Development Bank DDC District Development Committee DMG Department of Mines and Geology DOLIDAR Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads DOR Department of Roads DOS Department of Survey DWIDP Department of Water Induced Disaster Prevention EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EPA Environmental Protection Act EPR Environmental -

India's Development Assistance and Connectivity Projects in Nepal

India’s Development Assistance and Connectivity Projects in Nepal AUTHORS: SANJAY PULIPAKA, AKSHAYA SREE N R, M HARSHINI, DEEPALAKSHMI V R, KRISHI KORRAPATI 1 Disclaimer Opinions and recommendations in the report are exclusive of the author(s) and not of any other individual or institution including ICRIER. This report has been prepared in good faith on the basis of information available at the date of publication. All interactions and transactions with sponsors and their representatives have been transparent and conducted in an open, honest and independent manner as enshrined in ICRIER Memorandum of Association. ICRIER does not accept any corporate funding that comes with a mandated research area which is not in line with ICRIER’s research agenda. The corporate funding of an ICRIER activity does not, in any way, imply ICRIER’s endorsement of the views of the sponsoring organization or its products or policies. ICRIER does not conduct research that is focused on any specific product or service provided by the corporate sponsor. Submitted by: ICRIER Dated: May 20, 2018 Authors: Sanjay Pulipaka, Akshaya Sree N R, M Harshini, Deepalakshmi V R, Krishi Korrapati Image Details: Jomsom Bridge (Mustang District, Nepal) constructed with Indian assistance in 2017. Image Source: Indian Embassy, Kathmandu, Nepal. India’s Development Assistance and Connectivity Projects in Nepal 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgement 4 List of Abbreviations 5 1. SECTION ONE 7 Introduction 7 2. SECTION TWO 8 A Unique Relationship 8 3. SECTION THREE 11 Connectivity Projects 11 4. SECTION FOUR 24 Small Development Projects and Connectivity 24 5. SECTION FIVE 26 Trade and Transit 26 6. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport Department of Roads Development Cooperation Implementation Division (DCID) Jwagal, Lalitpur Public Disclosure Authorized Strategic Road Connectivity and Trade Improvement Project (SRCTIP) Improvement of Naghdhunga-Naubise-Mugling (NNM) Road Public Disclosure Authorized Environment and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Prepared by Environment & Resource Management Consultant (P) Ltd. JV with Group of Engineer’s Consortium (P) Ltd., and Udaya Consultancy (P) Ltd. Kathmandu Public Disclosure Authorized January, 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction The Government of Nepal (GoN) has requested the World Bank (WB) to support the improvements of existing roads that are of vital importance to the country’s economy and regional connectivity through the proposed Strategic Road Connectivity and Trade Improvement Project (SRCTIP). This project will support (a) Improvement of the existing 2-lane Nagdhunga-Naubise-Mugling (NNM) road (94.7 km on the pivotal north-south trade corridor connecting Kathmandu and Birgunj) to 2-lane Asian Highway standard; and (b) Upgrading of the Kamala-Dhalkebar-Pathlaiya (KDP) road of the Mahendra Highway (East West Highway) from 2-lane to 4-lane. This Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) report only assesses the environmental and social risks and impacts of the NNM road in accordance with the Government of Nepal’s (GoN) requirements and the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework (ESF) and relevant Environmental and Social Standards(ESSs). The KDP road is covered by a separate upstream Environmental and Social Assessment (ESA) based on pre-feasibility information since the feasibility study of KDP road has just commenced recently. The ESA will inform the detailed ESIA at the detailed design stage of the KDP road. -

Mugling Road

Draft Executive Summary of the Environmental Assessment Report Naryanghat-Mugling Road Government of Nepal Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Physical Planning and Works Department of Roads Upgrading of Narayanghat – Mugling Road (Chainage: km 2+425 – km 35+677) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized March 2013 (Draft Version) Public Disclosure Authorized MMM Group Ltd. (Canada) in JV with SAI Consulting Engineers (P) Ltd. (India) in association with ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd. (Nepal) & Total Management Services (Nepal) Draft Executive Summary of the Environmental Assessment Report Naryanghat-Mugling Road Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome APs Affected Peoples B/C Benefit/Cost BFC Barandabhar Forest Corridor BOQ Bill of Quantities CBO Community Based Organization CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CDO Chief District Officer CFC Compensation Fixation Committee CFUG Community Forest User Group CGI Corrugated Iron Ch. Chainage (km) CMS Consolidated Management Service Nepal (P) Ltd. DADO District Agriculture Dev Office dB (A) Decibel (A) DDC District Development Committee DFO District Forest Office DoR Department of Roads DWSC Department of Watershed and Soil Conservation EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Act EPR Environmental Protection Regulation FGD Focus Group Discussion FRCU Foreign Cooperation Unit, DoR FS Feasibility Study FY Fiscal Year GDP Gross Domestic -

SFD Report Itahari Nepal

SFD Report Itahari Nepal Final Report This SFD Report – Intermediate SFD level - was prepared by Environment and Public Health Organization (ENPHO) Date of production: 17/12/2018 Last update: 19/12/2018 Itahari Executive Summary Produced by: ENPHO Nepal SFD Report Itahari, Nepal, 2018 Produced by: Jagam Shrestha, Senior WASH Officer, ENPHO Rajendra Shrestha, Program Director, ENPHO ©Copyright All SFD Promotion Initiative materials are freely available following the open-source concept for capacity development and non-profit use, so long as proper acknowledgement of the source is made when used. Users should always give credit in citations to the original author, source and copyright holder. This Executive Summary and SFD Report are available from: www.sfd.susana.org Last Update: 18 February 2019 I Itahari Executive Summary Produced by: ENPHO Nepal extended in the area of 93.78 square kilometres and the population growth rate is SFD Level: 6.23 (MOPE, 2017) .Itahari sub-metropolitan Intermediate receives 41.6% of inter-district migration in the Tarai towns. The city is expanding at a higher Produced by: rate as it is located at prime location in the junction of major highway and other cities like Environment and Public Health Organization Dharan and Biratnagar. (ENPHO) The geographical position of the sub- Collaborating partners: metropolitan is 26o39’16.84” N and 87o16’59.18” E at the elevation of 110 meters from Mean Sea Level (MSL). It has a warm Status: and temperate climate with an average mean o Final SFD report daily temperature of 24.6 C. The average maximum and minimum daily temperatures Date of production: 21/12/2018 were 30.2oC and 19oC recorded from 1985 to 2017.