Olympic Games' Cultural Olympiad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE WESTERN ALLIES' RECONSTRUCTION of GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter a Thesis Subm

SPORTING DEMOCRACY: THE WESTERN ALLIES’ RECONSTRUCTION OF GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, University of Toronto © Copyright by Heather L. Dichter, 2008 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Olympic Charter 1956

THE OLYMPIC GAMES CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS 1956 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE CAMPAGNE MON REPOS LAUSANNE (SWITZERLAND) THE OLYMPIC GAMES FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES RULES AND REGULATIONS GENERAL INFORMATION CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS PIERRE DE GOUBERTIN WHO REVIVED THE OLYMPIC GAMES President International Olympic Committee 1896-1925. THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES IS NOT TO WIN BUT TO TAKE PART, AS THE IMPORTANT THING IN LIFE IS NOT THE TRIUMPH BUT THE STRUGGLE. THE ESSENTIAL THING IS NOT TO HAVE CONQUERED BUT TO HAVE FOUGHT WELL. INDEX Nrs Page I. 1-8 FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES 9 II. HULES AND REGULATIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 9 Objects and Powers II 10 Membership 11 12 President and Vice-Presidents 12 13 The Executive Board 12 17 Chancellor and Secretary 14 18 Meetings 14 20 Postal Vote 15 21 Subscription and contributions 15 22 Headquarters 15 23 Supreme Authority 15 III. 24-25 NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEES 16 IV. GENERAL RULES OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES 26 Definition of an Amateur 19 27 Necessary conditions for wearing the colours of a country 19 28 Age limit 19 29 Participation of women 20 30 Program 20 31 Fine Arts 21 32 Demonstrations 21 33 Olympic Winter Games 21 34 Entries 21 35 Number of entries 22 36 Number of Officials 23 37 Technical Delegates 23 38 Officials and Jury 24 39 Final Court of Appeal 24 40 Penalties in case of Fraud 24 41 Prizes 24 42 Roll of Honour 25 43 Explanatory Brochures 25 44 International Sport Federations 25 45 Travelling Expenses 26 46 Housing 26 47 Attaches 26 48 Reserved Seats 27 49 Photographs and Films 28 50 Alteration of Rules and Official text 28 V. -

Vi Olympic Winter G a M E S O S L O 1952

VI OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES OSLO 1952 PROGRAMME AND GENERAL RULES Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library IOC / CIO du Bibliothèque : Source VI OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES OSLO 1952 14-25 FEBRUARY PROGRAMME AND GENERAL RULES THE ORGANISING COMMITTEE FOR THE VI OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES OSLO 1952 yrarbiL COI / OIC ud euqèhtoilbiB : ecruoS ^(5 GCö<} yrarbiL COI / OIC ud euqèhtoilbiB : ecruoS INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE (I. 0. C.) FOUNDER Baron Pierre de Coubertin PRESIDENT J. Sigfrid Edström FORMER PRESIDENTS OF THE I. O. C. Vikelas (Greece) Baron Pierre de Cou'bertin (France) • Count Baillet-Latour (Belgium) HONORARY MEMBERS OF THE I. O. C. R. C. Aldao (Argentina) Count Clarence von Rosen (Sweden) Ernst Krogius (Finland) Frédéric-René Coudert (U. S. A.) t Sir Noel Curtis Bennett (Great Britain) Tliomas Fearnley (Norway) t Marquis Melcliior de Polignac (France) Sir Harold Luxton (Australia) EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE J. Sigfrid Edström, President Avery Brundage, Vice-President Count Alberto Bonacossa Colonel P. W. Scharroo Armand Massard Lord Burghiey yrarbiL COI / OIC ud euqèhtoilbiB : ecruoS MEMBERS ARGENTINA: Horacio Bustos Moron AUSTRALIA: Lewis Luxton H. R. Weir AUSTRIA: Ing. Dr. li.c. Manfred von Mautner Marlcliof BELGIUM: Baron de Trannoy R. W. Seeldrayers BRAZIL: Arnaldo Guinle Antonio Prado jr. Dr. J. Ferreira Santos CANADA: J. C. Patteson A. Sidney Dawes CHILE: Enrique O. Barbosa Baeza CHINA: Dr. C. T. Wang Dr. H. H. Kung Professor Shou-Yi-Tung CUBA: Dr. Miguel A. Moenck CZECHOSLOVAKIA: Professor G. A. Gruss DENMARK: Prince Axel of Denmark EGYPT: Moiiamed Talier Pasha FINLAND : J. W. RangeH Eric von Frenckell FRANCE: François Pietri Armand Massard Count de Beaumont GERMANY: Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg Dr. -

Lists of Addresses

LE COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIQUE 23 JUIN 1894 FONDATEUR: M. LE BARON PIERRE DE COUBERTIN 1863-1937 Président d’honneur des Jeux olympiques Commission exécutive: Président: M. Avery Brundage, 10, North La Salle Street, Chicago 2. Vice-président: M. Armand Massard, 30, rue Spontini, Paris XVIe . Membres: Colonel P.-W. Scharroo, Oostduinlaan 66, La Haye. Lord Burghley, Tilton, Catsfield, nr. Battle, Sussex (England). S. A. R. le Prince Axel de Danemark, Bernstorffshoj, Gentofte (Danemark). Mohamed Taher Pacha, rue Champollion 2, Le Caire. Chancellerie du C. I. O.: Adresse: Mon Repos, Lausanne (Suisse). Télégrammes: CIO, Lausanne. Tél. 22 94 48. Chancelier: M. Otto Mayer, Mon Repos, Lausanne. Secrétaire: M me L. Zanchi, Mon Repos, Lausanne. LISTE DES MEMBRES DU C. I. O. Allemagne: Le Dr H.-H. Kung (1939), Bank of China, 40, Wal Street, New-York, U. S. A. S. A. le duc Adolphe-Frédéric de Mecklembourg Professeur Shou-Yi-Tung (1947), c/o. All China (1926), Schloss Eutin, Holstein. Athletic Federation, 16, Tung Chang an Street, D r Karl Ritter von Halt (1929), Lenbachplatz 2, Pekin (Chine). München 2. Argentine: Colombie: M. Enrique Alberdi (1952), Corrientès 222, Buenos- M. Julio Gerlein Comelin (1952). Aires. Cuba: Australie: Le D r Miguel A. Moenck (1938), O’Reilly No 407, M. Hugh Weir (1946), Scottish House, 19, Bridge La Havane. Street, Sydney. M. Lewis Luxton (1951), Shell Corner, 163, William Danemark: Street, Melbourne. S. A. R. le prince Axel de Danemark (1932), Bern- storffshoj, Gentofte, Danemark. Autriche: Ing. Dr h. c. Manfred Mautner Ritter von Markhof Egypte: (1947), Landstrasse- Hauptstrasse 97, Vienne III. -

Olympic Charter 1966

THE OLYMPIC GAMES CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS 1966 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE CAMPAGNE MON-REPOS LAUSANNE SWITZERLAND THE OLYMPIC GAMES FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES RULES AND REGULATIONS RULES OF ELIGIBILITY GENERAL INFORMATION CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not to win but to take part, just as the most important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle. The esse?itial thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well. PIERRE DE COUBERTIN Founder of the Modern Olympic Games President of the International Olympic Committee IS9f>-l92.'> INDEX Articles Page FIRST PART I. 1-8 Fundamental principles II II. Rules and Regulations of the International Olympic Committee 9 Objects and Powers 13 10 Membership 13 12-17 Organization 14 18 Meetings 16 20 Postal Vote 16 21 Subscription and contributions 17 22 Headquarters 17 23 Supreme Authority 17 III. 24-25 National Olympic Committees 18 IV. General Rules of the Olympic Games 26 Definition of an Amateur 21 27 Necessary Conditions for wearing the colours of a Country 21 28 Age Limit 22 29 Participation of Women 22 30 Program 22 31 Fine Arts 23 5 32 Demonstrations 23 33 Olympic Winter Games 23 34 Entries 24 35 Number of Entries 25 36 Travelling Expenses 25 37 Housing 26 38 Team Officials 26 39 Technical Delegates 27 40 Technical Officials and Juries 27 41 Final Court of Appeal 28 42 Penalties in case of Fraud 28 43 Prizes 28 44 Roll of Honour 29 45 Explanatory Brochures 30 46 International Sport Federations 30 47 Attaches 31 48 Reserved Seats 31 49 Publicity 32 50 Alterations of Rules and Official Text 33 V. -

Copyright by Sam Thomas Schelfhout 2017

Copyright by Sam Thomas Schelfhout 2017 The Thesis Committee for Sam Thomas Schelfhout Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: “It is ‘Force Majeure’”: The Abrupt Boycott Movements of the 1956 Melbourne Summer Olympic Games APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Thomas M. Hunt, Supervisor Matthew T. Bowers “It is ‘Force Majeure’”: The Abrupt Boycott Movements of the 1956 Melbourne Summer Olympic Games by Sam Thomas Schelfhout, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Kinesiology The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Dedication To my mother Debbie, my father Tom, and my brother Riley for always being there for me Acknowledgements My time at the University of Texas at Austin would not have been possible without the wonderful support system I have around me. I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Thomas Hunt, for leading me in the right direction and for his constructive criticism throughout the writing process. He has helped me make sense of each of the challenges that have been thrown in my way and has always managed to set time aside for me with whatever I need help with. He also deserves full credit for allowing me access to the Avery Brundage Collection, of which this work would not have been possible without. I am also indebted to Dr. Matthew Bowers, who has taken an active role in my master’s education from my first day on the Forty Acres and has always gone out of his way to provide me with opportunities to pursue my academic and career goals. -

The Biographies of All Loc-Members

HJ'.' coil 43 The Biographies of all lOC-Members Part VIII No. 142 | Miguel Moises SAENZ | Mexico IOC member: No. 142 Replacing Gomez de Paranda Born: 13 Ferbuary 1888, Monterrey/Mexico Died: 24 October 1941, Lima/Peru Co-opted: 25 July 1928 Resigned: 7 June 1933 Attendance at Session Present: 0 Absent: 4 As a distinguished student at local schools and Colleges he was given a government graut to continue his studies abroad. He attended Washington & Jefferson and Columbia University in America and the Sorbonne in Paris. He obtained a Bachelor of Science degree at Washington & Jefferson and a Bachelor of Arts degree at Columbia. On his return to Mexico, he held va rious g overnment posts in the field of education which led to his being appointed the Minister of Education. He spent time studying the habits of the indigenous Indians in Canada and later in South America where he visited Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. He wrote books an his ex periences in both locations. In 1934 he was appointed Ambassador to Ecuador, the following year he became Ambassador to Denmark and in 1937 he was made Ambassador to Peru. This proved to be his final diplomatic post as he died in Lima four years after his appointment. He was the organiser of Mexico's first Olympic c participation in 1924 and of the Central American Games in 1926. Although he was unable to attend any of the four IOC Sessions held during his mandate he was the first Mexican IOC member who truly embraced the Spirit of Olym pism. -

The Early Relationship Between UNESCO and the IOC: Considerations – Controversies – Cooperation

The early relationship between UNESCO and the IOC: Considerations – Controversies – Cooperation Caroline Meier Institute of Sport History/ Olympic Studies Centre German Sport University Cologne [email protected] Abstract Today, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation is “the United Nations’ lead agency for physical education and sport”. It runs several projects and initiatives and it closely cooperates with various international organisations that are engaged in the field of sport and physical education. The questions as to how and why sport became part of UNESCO’s programme and who were the involved participants, however, remain unanswered in academic literature. This article shows that after the introduction of the idea to include sport and physical education in its programme by individual sports officials, with members of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) playing a key role, UNESCO had to overcome severe controversies, jealousies and power struggles when trying to position itself in the field. Particularly, the relationship between UNESCO and the IOC was difficult – the general problems of international sports, and consequently the IOC, were mirrored in the process of UNESCO’s early involvement in sport. In order to elucidate the development of UNESCO’s engagement in international sport until the early 1970s, the research utilises the qualitative research method of hermeneutics and analyses archive material from the Carl und Liselott Diem-Archive at the German Sport University Cologne, the IOC Archive in Lausanne, the UNESCO Archive in Paris and the Avery Brundage Collection of the University of Illinois at Aubana-Champaign Archives. Keywords UNESCO, IOC, fair-play trophy, 10th Olympic Congress Varna, apolitical sport, amateurism, educational value of sport. -

Olympic Sports (2)” of the James M

The original documents are located in Box 25, folder “Olympic Sports (2)” of the James M. Cannon Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Citius-Aitius-Forti us Repertoire Olympique Olympic Directory 1975 Digitized from Box 25 of the James M. Cannon Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library , ' ! ~ ·~ ~ E ! -C> ·- 0 u ..CD ·-a. ·c; E t:~ CD 0 a. '-CD a: a; en c: en .2 a: 0::J ::i• "tJ- e -~ a. ~ Q) 0. ~ E 0 Q) () "tJ , SOMMAIRE Comlt6 International Olymplque CONTENTS Pages Cree le 23 juin 1894. Fondateur : le baron Pierre de Coubertin 1. Comite International Olympique International Olympic Committee 3 Created 23rd June, 1894. Founder : Baron Pierre de Coubertin Lisle des presidents du C.I.O. List of I.O.C. Presidents 3 Commission executive Executive Board 4 Secretariat general General Secretariat 5 Lisle des pr6sldents du C.I.O. 2. Lisle alphabetique des membres du C.I.O. -

CATALOGUE 45 ‐ 2018 Nouveaux Prix En Baisse (‐50%) Annule Et Remplace Le 44‐2017 L’ANTIQUAIRE De L’ESCRIME Magasin Créé En 1980

le Catalogue n° 44 automne 2016 : gras & souligné : articles nouveaux ‐ 1 ‐souligné : exemplaire différent CATALOGUE 45 ‐ 2018 Nouveaux prix en baisse (‐50%) Annule et remplace le 44‐2017 L’ANTIQUAIRE de l’ESCRIME Magasin créé en 1980 8 Place Beaumarchais (Clair Village) F. 91600 SAVIGNY sur Orge Jacques Castanet : Prof. E.P.S. ‐ Maître d’Armes Tél : 01 78 84 63 50 Port : 06 64 37 77 76 Site : www.antiquaire‐escrime.fr email : castanet@antiquaire‐escrime.fr Sur le Thème ESCRIME et DUEL environ 4000 articles en magasin ! LIVRES : du XVII° à nos jours (plus de 500 livres disponibles) Nombreux livres « de cape et d’épée » à petit prix STATUETTES : bronze, régule ou autres matériaux + MEDAILLES ESCRIME FÉMININE : objets et documents spécifiques Equipements et pièces détachées anciens : appareils électriques, masques, tenues, plastrons, lames, gardes, poignées, pommeaux, etc… BREVETS de Maitre, de Prévôt, de canne ou de bâton PLANCHES : d’ouvrages du XVI° au XIX° TABLEAUX encadrés ou non CARTES POSTALES & Chromos ARMES : fleurets, épées, sabres : d’entraînement, de compétition ou de Duel DOCUMENTS divers : revues, journaux, illustrations PROGRAMMES de compétitions d'escrime, de 1851 à nos jours AFFICHES de films de « cape et d’épée « ou de grandes compétitions PHOTOS d’agence de presse (en très grand nombre) LIVRES & DOCUMENTS sur la Boxe Française, la Canne, le Bâton, les J.O… EXPOSITION ‐VENTE pendant certaines grandes compétitions. CONFERENCES «Histoire du Duel en France », « le Coup de Jarnac », « Le Chevalier de St‐Georges » (musicien‐escrimeur du XVIII° siècle) INTERVIEWS dans le «magasin – musée» pour journaux ou télévision Catalogue n°45 gras & souligné : article nouveau ; souligné seul : exemplaire différent. -

Statistik-Historisch.Pdf

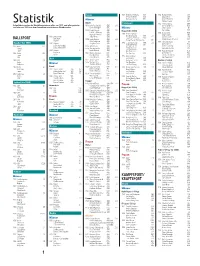

Tennis 19 24 Wightman/Williams USA 19 52 Nathan Brooks USA Jessup/Richards USA Edgar Basel GER Männer Bouman/Timmer NED Anatoli Bulakow URS William Toweel RSA Statistik Einzel Tischtennis 1956 Terence Spinks GBR Aufgeführt werden die Medaillengewinner aller vor 1972 und aller geänder - 1896 John Pius Boland GBR 3:0 Mircea Dobrescu ROU ten oder vor 2016 aus dem Programm gestrichenen Wettbewerbe. Demis Kasdaglis GRE Männer John Caldwell IRL 19 00 Hugh Doherty GBR 3:0 Doppel (bis 2004) René Libeer FRA Harold S. Mahony GBR 1988 Chen Long-Can/ 1960 Gyula Török HUN Reginald Doherty GBR Sergej Siwko URS 1960 Jugoslawien 3:1 A.B.J. Norris GBR Wie Qing-Guang CHN 2:1 Lupulescu/Primorac YUG Kiyoshi Tanabe JPN BALLSPORT Dänemark 1908 Josiah Ritchie GBR 3:0 Abdelmoneim El Guindi EGY Ungarn An Jae Hyung/Yoo Nam-Kyu KOR Otto Froitzheim GER 1964 Fernando Atzori ITA Baseball (bis 2008) 1964 Ungarn 2:1 Vaughan Eaves GBR 1992 Lu Lin/Wang Tao CHN 3:2 Roßkopf/Fetzner GER Arthur Olech POL Tschechoslowakei Robert Carmody USA 1992 Kuba 11:1 1908 Arthur Gore GBR 3:0 Kang Hee Chan/ Deutschland (DDR) Stanislaw Sorokin URS Taiwan Halle George Caridia GBR Lee Chul Seung KOR Japan 1968 Ungarn 4:1 Josiah Ritchie GBR Kim Taek Soo/ 19 68 Ricardo Delgado MEX 1996 Kuba 13:9 Bulgarien 1912 Charles Winslow RSA 3:1 Yoo Nam Kyu KOR Arthur Olech POL Japan Servilio de Oliveira BRA Japan Harold Kitson RSA 1996 Kong Linghui/ USA Oscar Kreuzer GER Leo Rwabwogo UGA Golf Liu Guoling CHN 2000 USA 4:0 1912 Andre Gobert FRA 3:0 Wang Tao/Lu Lin CHN Bantam (-56 kg) Kuba Männer Halle Charles Dixon GBR Yoo Nam-Kyu/ 1920 Clarence Walker RSA Südkorea Anthony Wilding AUS Lee Chul-Seung KOR Chris J. -

Olympic Charter 1950

tl and the Modern Olympic Games CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS 1950 YOU WILL BE A TRUE SPORTSMAIV As an athlete... 1. If you take part in sport for the love of it; 2. If you practise it in an unselfish way ; 3. If you follow the advice of those who have had experience; 4. If you accept without question the decisions of the Jury or of the Umpire; 5. If you win without conceit and lose without bitterness ; 6. If you prefer to lose rather than to win by discourteous or unfair means; 7. If outside the stadium as well as in every action of your life you behave yourself in a way that is sporting and fair. As a spectator... I. In applauding the winner yet cheering the loser; In laying aside prejudice towards club or country; In respecting the decision of the Jury or of the Umpire, even if you don't agree with it; In drawing useful lessons out of a viaory or a defeat; In behaving in a dignified manner during a sporting event, even when your team is playing; In acting always on every occasion, whether in or outside the sta dium, with dignity and sportsmanship. vV^^-C4. ^ ^C/l^t^C^cS/cX^ COUNT HENRY DE BAILLET-LATOUR President of the I. O. C. from 192s to 1941. Mr. J. SiGFRiD EDSTROM President of the I. O. C. since 1946. PIERRE DE COURERTIIV Reviver of the Olympic Games Honorary President of the Olympic Games Pierre de Fredi, Baron de Coubertin, was born in Paris on January 1st.