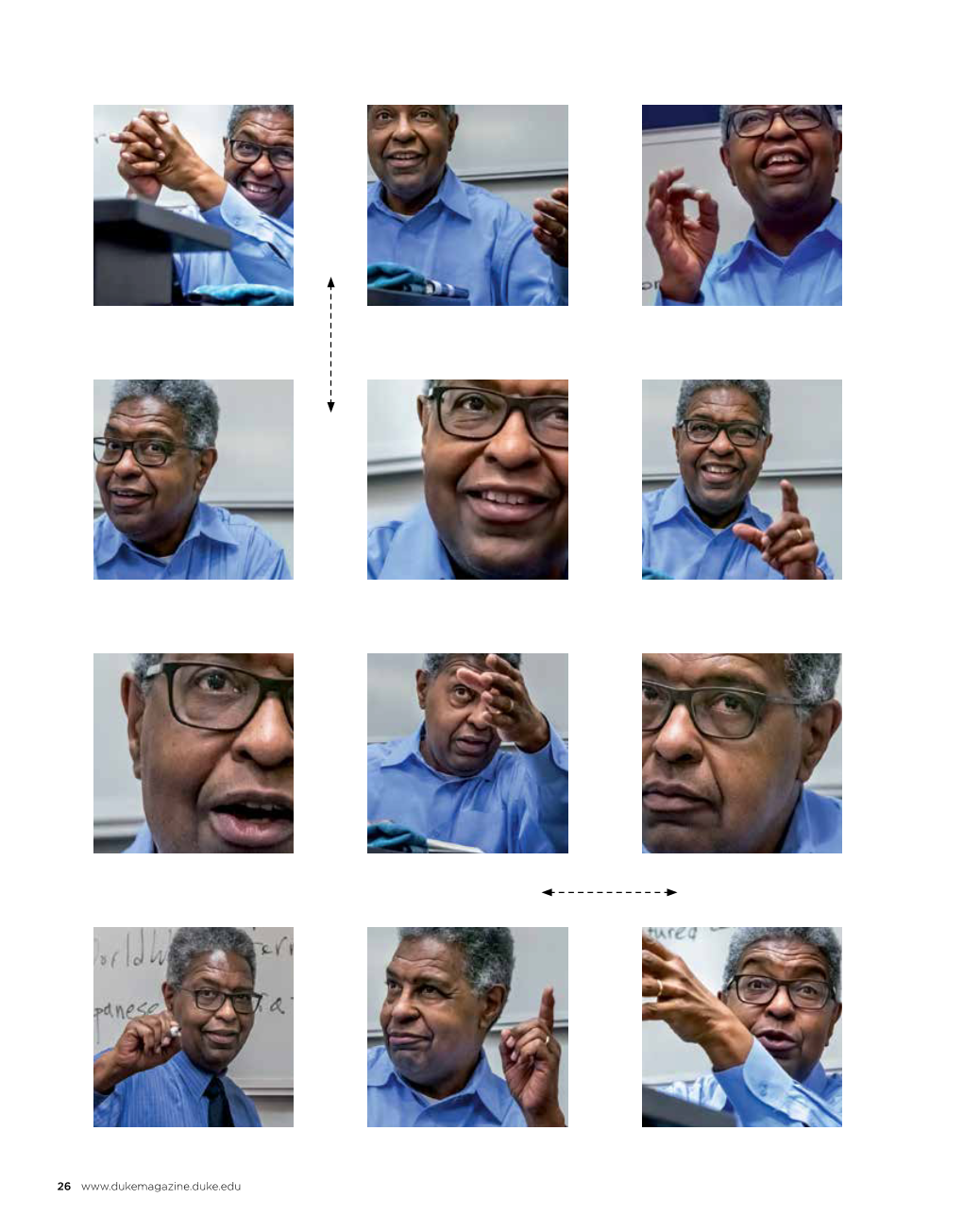

26 Sandy Darity Has Some Thoughts About INEQUALITY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tressie-Mcmillan-Cottom-CV-Fall

TRESSIE MCMILLAN COTTOM, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Virginia Commonwealth University 827 West Franklin Street, Founder’s Hall, Office 224 Richmond, VA. 23284 (804) 828-0734 | [email protected] http://www.tressiemc.com http://www.thickthebook.com ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor 2019 - Present Department of Sociology, Virginia Commonwealth University Faculty Affiliate 2015 - Present Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Harvard University Assistant Professor 2015 - 2019 Department of Sociology, Virginia Commonwealth University EDUCATION Laney Graduate School, Emory University | 2015 Doctor of Philosophy, Emory College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Sociology Dissertation: Becoming Real Colleges in the Financialized Era of U.S. Higher Education Committee: Richard Rubinson (chair), Irene Browne, Cathy Johnson, Roberto Franzosi, Carol Anderson North Carolina Central University | 2009 Bachelor of Arts, English and Political Science PUBLICATIONS | Books McMillan Cottom, Tressie. 2019. THICK: And Other Essays. New York: The New Press. • National Book Award, Finalist for Non-fiction, 2019 • Brooklyn Public Library Literary Prize, Shortlist for Non-fiction, 2019 • New York Times Editor’s Choice McMillan Cottom, Tressie. 2017. Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profits. New York: The New Press. • Translation, Traditional Chinese: McMillan Cottom, Tressie. 2019. Dījí Jiàoyù 低級教育. Taipei City, Taiwan: Hizashi Publishing. PUBLICATIONS | Edited Volumes McMillan Cottom, Tressie and William, Darity A., Jr., eds. 2016. For-Profit U: The Growing Role of For- Profit Colleges in U.S. Higher Education. Palgrave MacMillian. Gregory, Karen, McMillan Cottom, Tressie, and Daniels, Jessie eds. 2016. Digital Sociologies. UK Bristol Policy Press. Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom 2 PUBLICATIONS | Articles Siddiqi, A., Sod-Erdene, O., Hamilton, and McMillan-Cottom, T. -

Mitigate That Impact, Empowering Faculty to Create More Welcoming, Inclusive Classrooms

mitigate that impact, empowering faculty to create more welcoming, inclusive classrooms. She will also meet with Black women students for an informal breakfast Q&A, serving as a role model of Black, female excellence and providing a unique opportunity for students to engage with a leading scholar in an intimate setting. Finally, in an evening lecture and book signing open to all of campus and the public, and free to attend, Dr. McMillan Cottom will speak about her recent collection, THICK: and Other Essays, a Black women’s cultural bible which intertwines the personal, social, and political. Success of this project will be measured by attendance at each event and level of speaker/audience interaction. This proposal connects to several important goals of the University and of Women of Excellence. Bringing Dr. McMillan Cottom to campus will support Xavier’s goal to promote diversity education, scholarship, and culturally responsive teaching, and uphold the social justice ethos at the heart of our Jesuit values. These events will bring together constituent groups—students, alumni, faculty, staff, and community members—in critical conversations about gender and race and also honor and extend the legacies of women and women of color who have been historically underrepresented at Xavier, and in our communities and world. In addition, hosting such a prominent scholar as Dr. McMillan Cottom will enhance the reputation of Xavier University as a leader on issues of gender, racial, and class diversity. NARRATIVE Please provide a detailed project description (in #1) and answer the questions below (#2 - #8) Limit the length of your answers (including project description) to three single-spaced, typed pages. -

Curriculum Vitae

TRESSIE MCMILLAN COTTOM | curriculum vitae Virginia Commonwealth University 827 West Franklin Street Founder’s Hall Office 224 Richmond VA 23284 [email protected] | (804) 828-0734 www.tressiemc.com ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE | employment & education Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2015-present Faculty Affiliate, Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Harvard University, 2015-present Ph.D., Sociology, Emory University (2015) Dissertation: Becoming Real Colleges in the Financialized Era of U.S. Higher Education. Committee: Richard Rubinson (chair), Carol Anderson, Irene Browne, Roberto Franzosi, Cathy Johnson B.A., English and Political Science, N.C. Central University (2009) PUBLICATIONS | book McMillan-Cottom, Tressie. 2017. Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profits. New York: The New Press. PUBLICATIONS | edited volumes McMillan Cottom, Tressie and William Darity, Jr., eds. 2017. For-Profit U: The Growing Role of For-Profit Colleges in U.S. Higher Education. Palgrave McMillan. Gregory, Karen, Tressie McMillan Cottom, and Jessie Daniels, eds. 2016. Digital Sociologies. UK Bristol Policy Press. PUBLICATIONS | articles McMillan-Cottom, T. & Angulo, A. In Press. “BLM: A Radical 21st Century Education Policy Platform”, Harvard Journal of Black Public Policy. McMillan-Cottom, T., Johnson, J., Stamm, T., & Honnold, J. In Press. “A Vision Among Challenges: Lessons about Online Teaching from the First Online Master’s Degree in Digital Sociology.” The Journal of Public and Professional Sociology. McMillan-Cottom, T. 2016. “Having It All Is Not A Feminist Theory of Change.” Signs. 42(2):2-6. McMillan-Cottom, T. 2016. “More Scale, More Questions: Observations on Textual Analysis From Sociology.” In Gold M. & Klein L. (Eds.), Debates in the Digital Humanities (pp. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE PODCAST RHETORICS INSIGHTS INTO PODCASTS AS PUBLIC PERSUASION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MATTHEW VINCENT JACOBSON Norman, Oklahoma 2021 PODCAST RHETORICS INSIGHTS INTO PODCASTS AS PUBLIC PERSUASION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. William Kurlinkus, Chair Dr. Bill Endres Dr. Justin Reedy Dr. Roxanne Mountford Dr. Sandra Tarabochia © Copyright by MATTHEW VINCENT JACOBSON 2021 All Rights Reserved. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . viii Abstract . xii Chapter 1: The Argument for Rhetorically Analyzing Podcasts . 1 I. Introduction . 2 II. Rhetorically Defining Podcasts . 5 III. A Call for Podcast Scholarship . 14 IV. Podcast Scholarship in Rhetoric and Writing Studies . 18 V. The Need to Rhetorically Analyze Podcast Rhetoric . 24 VI. Introducing Three Analytics of Podcasting: Technology, Sonic, and Conversational Rhetorics in a Public Argument Over Mask Wearing in The Joe Rogan Experience . 28 VII. Project Overview . 44 Chapter 2: The Technological Horizons of Podcast Persuasion . 45 Chapter 3: The Sounds of Podcast Rhetoric . 47 Chapter 4: Deliberation or Demagoguery? The Rhetoric of Podcast Conversations . 50 Chapter 2: The Technological Horizons of Podcast Persuasion . 53 I. Introduction . 54 II. Rhetorical Theories of Philosophy of Technology . 55 III. The Technological Rhetoric of Podcast Technologies . 64 A. The Rhetoric of Podcasting’s Regulatory Context in the U.S. and the Standing Reserve of Internet Audiences . .64 B. The Rhetoric of Production and Post-Production Tech . .72 v C. The Rhetoric of Distribution and “Listening” Tech . 98 D. -

Action on Education Friday, February 27 - Saturday, February 28, 2015 Diana Center, Barnard College

The Scholar & Feminist Conference XL Action on Education Friday, February 27 - Saturday, February 28, 2015 Diana Center, Barnard College This conference was made possible by generous funding from the Virginia C. Gildersleeve Fund from the Barnard College Provost’s Office. Barnard was founded 125 years ago with the feminist mission of providing education to those who were excluded from major avenues of education. In honor of this legacy and the 40th anniversary of BCRW’s signature Scholar & Feminist Conference, this year’s conference builds a feminist framework for understanding the institutional, social, and pedagogical facets of teaching and learning. Scholars, activists, educators, and artists explore the K-12 landscape and higher education, investigating who can attain post-secondary education, under what circumstances, and at what cost. They discuss diverse feminist approaches to such topics as the Common Core standards, educational alternatives, the school-to-prison pipeline, teaching intersectional feminism, adjunct labor, sexual violence on campus, continuing racial and economic segregation within educational spaces, and feminist visions for a fair and just educational system. Friday, February 27 10:00 AM Welcome Janet Jakobsen and Tressie McMillan Cottom Event Oval, The Diana Center 10:30 AM Plenary Presentations The Octopus: Cognitive Capitalism and the University Natalia Cecire, Miriam Neptune, Nicci Yin It has often been remarked in recent years that we have entered a second Gilded Age of capitalist deregulation and socioeconomic inequality, with patterns of a hundred years ago repeating themselves. And while the rhetoric around the university is that it affords social mobility, as tuition and student debt have risen and affirmative action and need-blind admission have been revoked, it has become increasingly apparent that the university is an engine of that inequality. -

Allyship and Antiracism Reading List

ROCKY TOPICS: ALLYSHIP AND ANTIRACISM READING LIST Racial Justice Resources Compiled by the UTK Women, Gender and Sexuality Program and Dr. Patrick R. Grzanka 75 Actions for Racial Justice: https://medium.com/equality-includes-you/what-white-people-can-do-for-racial- justice-f2d18b0e0234 How to be an Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TzuOlyyQlug The African American Policy Forum: https://aapf.org INCITE! Women of Color Collective: https://incite-national.org/resources-for-organizing/ Black Mama’s Bail Out: https://nationalbailout.org/black-mamas-bail-out/ Locally: @knoxvillesblackmamasbailout The Bail Project: bailproject.org Race: The Power of an Illusion (film and resources) https://www.racepowerofanillusion.org/ Dismantling Racism Resources: https://www.dismantlingracism.org/resources.html?fbclid=IwAR1qLTwd- kD6p23tYmrhzqJjvYGyZv5aGFNRVlz9e5N2wttug3jcLub3wWE Black Feminism & the Movement for Black Lives: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eV3nnFheQRo&feature=youtu.be Philadelphia MOVE Bombing Documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpbGgysqE4c The 1619 Project: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america- slavery.html (also available at lib.utk.edu) 30+ Resources to Help White Americans Learn about Race and Racism: https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/07/white-americans-learn-race/ Movement for Black Lives: https://m4bl.org (see especially The Platform) Southerners on New Ground: https://southernersonnewground.org Reading toward Abolition: A Reading List on Policing Rebellion, and -

TRESSIE MCMILLAN COTTOM, Ph.D

TRESSIE MCMILLAN COTTOM, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Virginia Commonwealth University 827 West Franklin Street, Founder’s Hall, Office 224 Richmond, VA. 23284 (804) 828-0734 | [email protected] http://www.tressiemc.com ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor 2019 - Present Department of Sociology, Virginia Commonwealth University Faculty Affiliate 2015 - Present Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Harvard University Assistant Professor 2015 - 2019 Department of Sociology, Virginia Commonwealth University EDUCATION Laney Graduate School, Emory University | 2015 Doctor of Philosophy, Emory College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Sociology Dissertation: Becoming Real Colleges in the Financialized Era of U.S. Higher Education Committee: Richard Rubinson (chair), Irene Browne, Cathy Johnson, Roberto Franzosi, Carol Anderson North Carolina Central University | 2009 Bachelor of Arts, English and Political Science PUBLICATIONS | Books McMillan Cottom, Tressie. 2019. THICK: And Other Essays. New York: The New Press. • National Book Award, Finalist for Non-fiction, 2019 • Brooklyn Public Library Literary Prize, 2019 • New York Times Editor’s Choice McMillan Cottom, Tressie. 2017. Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profits. New York: The New Press. • Translation, Traditional Chinese: McMillan Cottom, Tressie. 2019. Dījí Jiàoyù 低級教育. Taipei City, Taiwan: Hizashi Publishing. PUBLICATIONS | Edited Volumes McMillan Cottom, Tressie and William, Darity A., Jr., eds. 2016. For-Profit U: The Growing Role of For- Profit Colleges in U.S. Higher Education. Palgrave MacMillian. Gregory, Karen, McMillan Cottom, Tressie, and Daniels, Jessie eds. 2016. Digital Sociologies. UK Bristol Policy Press. Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom 2 PUBLICATIONS | Articles Siddiqi, A., Sod-Erdene, O., Hamilton, and McMillan-Cottom, T. 2019. “Growing sense of social status threat and concomitant deaths of despair among whites.” SSM Journal of Population Health. -

Carolina Alumni Review November/December 2020 $9

CAROLINA ALUMNI REVIEW NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2020 $9 ND2020_CAR.indd 1 10/28/2020 10:57:57 AM ND2020_CAR.indd 2 10/28/2020 10:59:26 AM ON THE COVER: A majestic maple tree shows off its colors in front of Wilson Hall just off South Road. In the background is the Phi Delta Theta house on Columbia Street. FEATURES | VOL. 109, NO. 6 PHOTO: UNC/CRAIG MARIMPIETRI UNC/JON GARDINER ’98 Science Project 36 Just a planetarium? A Morehead dream that started decades ago is coming to reality: The grand building will showcase all of UNC’s sciences. BY DAVID E. BROWN ’75 Franklin in Hibernation 42 Of course we’re staying home. We’re eating in. We’re mastering self-entertainment. But you sort of have to see The Street in pandemic to believe it. ▲ ▼ ALEX KORMANN ’19 GRANT HALVERSON ’93 PHOTOS BY ALEX KORMANN ’19 AND GRANT HALVERSON ’93 Stateside Study Abroad 52 Zoom has its tiresome limitations. Not as obvious are new possibilities — such as rethinking a writing class as an adventure on the other side of the world. BY ELIZABETH LELAND ’76 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER ’20 1 ND2020_CAR.indd 1 10/28/2020 12:13:14 PM GAA BOARD OF DIRECTORS, 2020–21 OFFICERS Jill Silverstein Gammon ’70, Raleigh .......................Chair J. Rich Leonard ’71, Raleigh ...............Immediate Past Chair Dana E. Simpson ’96, Raleigh ........................Chair-Elect Jan Rowe Capps ’75, Chapel Hill .................First Vice Chair Mary A. Adams Cooper ’12, Nashville, Tenn. Second Vice Chair Dwight M. “Davy” Davidson III ’77, Greensboro . Treasurer Wade M. Smith ’60, Raleigh .............................Counsel Douglas S. -

The New Press Reading Group Guide

The New Press Reading Group Guide Thick And Other Essays by Tressie McMillan Cottom QUESTIONS 1. In the opening essay of Thick, McMillan Cottom discusses the many ways in which she is proudly contradictory. What contradictions does she highlight? What might cause the author— or anyone—to frame aspects of their identity as contradictory? Think about the contradictions you embody and share them with your discussion group. Do you feel misread or reduced on a regular basis? How do you assert your complexity, your “thickness,” in a world that wants you to be conveniently “thin”? 2. In “In the Name of Beauty,” McMillan Cottom complicates widely accepted definitions of beauty and challenges readers to consider the function and purpose of beauty. Discuss what concepts shape your own definition of beauty and how you apply notions of beauty or ugliness to yourself. Using your own observations, can you think of examples of hypocrisy in mainstream feminist discourses surrounding beauty? 3. In the same essay, McMillan Cottom says that “if beauty is to matter at all for capital, it can never be for black women.” What point do you think the author is making by identifying people as “economic subjects” in this essay? 4. Discuss among yourselves: is there a way the concept of beauty can be made liberatory? What would that look like in a capitalist society? Consider McMillan Cottom’s term “discursive loy- alty”—why are the stakes for integrating an inclusive vision of beauty into our politics so high? 5. Laced throughout “In the Name of Beauty” is McMillan Cottom’s reckoning with the effect her messages about beauty have on other black women. -

Call for Papers

CALL FOR PAPERS 36th Annual SEUSS: South Eastern Undergraduate Sociology Symposium “Sociology Today: From Inquiry to Action” February 16th-17th, 2018 Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia The 36th annual SEUSS will be held Friday and Saturday, February 16th/17th at Emory University. The Symposium provides undergraduate students a unique opportunity to present their independent research in a welcoming professional meeting. Presentations in any area of sociological significance are invited. OPENING BANQUET The keynote speaker for the banquet on Friday, February 17th, 2018 will be Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and Faculty Associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. Her book, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise for For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy (2017, The New Press) has received national and international acclaim. Professor Cottom serves on dozens of academic and philanthropic boards and publishes widely on issues of inequality, work, higher education and technology. Her research on higher education, work and technological change in the new economy has been supported by the Microsoft Research Network’s Social Media Collective, the Kresge Foundation, the American Educational Research Association and the UC Davis Center for Poverty Research. Her public scholarship has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Slate, and The Atlantic. You can read more at www.tressiemc.com. APPLICATION PROCEDURE 1. Students interested in presenting a paper should submit an abstract of their research that is no longer than 300 words. The abstract must include the student’s full name and institution. The deadline for receipt of abstracts is 5pm on Monday, January 22nd, 2018. -

A Sociologist with a National Best-Selling Book Detailing the Rise

A sociologist with a national best-selling book detailing the rise of for-profit colleges, growing debts from student loans and their impact on social inequality will give a public talk at UNC Charlotte on Thursday, Oct. 18. Tressie McMillan Cottom, an award-winning author and assistant professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, will speak on her book, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy. The talk, at 7 p.m. in Cone University Center’s After Hours Room, is open free of charge to the campus and broader community. Cottom frames the discussion about for-profit institutions as part of a larger set of educational reforms, and political and economic trends that public education faces. Cottom’s work has been featured by The Washington Post, on NPR’s Fresh Air, The Daily Show, The New York Times, Slate, and The Atlantic, among others. A former Charlotte resident, she was part of a panel discussion on the topic of for-profit colleges on Charlotte Talks on WFAE in August. http://www.wfae.org/post/charlotte-talks-more-profit-colleges-close-their-doors- do-students-get-what-they-pay#stream/0 Her book considers the intersection of the rise of for-profit higher education, the student debt crisis, the new economy, and the role of these factors in the reproduction of race/class/gender inequality. A book review in The New York Times called it “…the best book yet on the complex lives and choices of for-profit students.” Other reviews also have praised the book. -

Spring 2017 an HKS Student Publication United States of America Office of the MEMORANDUM Harvard Kennedy School Journal Of

Spring 2017 United States of America Office of the MEMORANDUM Harvard Kennedy School Journal of African American Public Policy An Movement for Black Lives _____ black vision __________________________________________________ __ _ _____________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________ _______________ _ _________________________ _ _____________________________________ “black revolution” ___ ______ ___ _ An HKS Student Publication The Harvard Kennedy School Journal of African American Public Policy is a student publication at the Harvard Kennedy School. All views expressed in the journal are those of the authors or interviewees only and do not represent the views of Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, and the staff of the Harvard Kennedy School Journal of African American Public Policy or any of its affiliates. © 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Except as otherwise specified, no article or portion herein is to be reproduced or adapted to other works without the expressed written consent of the editors of the Harvard Kennedy School Journal of African American Public Policy. ISSN# 1081-0463 Table of Contents Editor’s Note Trayvon, Rest in Power 5 by Derecka Purnell 17 by Sara Trail Teaching the M4BL Policy Platform Movement Movement for Black Black Lives Matter and 9 Lives Policy 18 the Law Roundtable by Justin Hansford M4BL Policy Platform, Law, Protests, and 12 English 22 Social Movements: A Syllabus by Amanda Alexander M4BL Policy Platform, A Radical