Mychessexcerpt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chess Viewer the Power of XSL Lies in Its Ability to Perform Radical Transformations of the XML Data Source

DEVELOPER'S ZONE SHOP SEARCH Products Demos Stories Solutions Support Download Customers Partners Company Sitemap Chess Viewer The power of XSL lies in its ability to perform radical transformations of the XML data source. This page contains yet another proof for this fact: you can build a chessgame viewer with a stylesheet! The source document is a transcription of a chess game played by Garry Kasparov against a chess supercomputer -- IBM Deep Blue. The game is encoded in a form resembling the well-known Portable Game Notation (PGN) format. The source is very compact: a sample game on this page [DeepBlue.xml] is less than 4 kBytes in size. The stylesheet converts this arid text into a sequence of board diagrams, drawing every intermediate position as a graphical image (a special chess font is used). Applying a 23 kB stylesheet [chess.xsl], we get a 415 kBytes (!) FO stream [DeepBlue.fo]. These numbers give an idea of how deep the transformation is. The final step of the whole procedure consists in converting the result into PDF using XEP. The resulting PDF file [DeepBlue.pdf] is much smaller than the source FO stream -- less than 90 kBytes. (XEP implements PDF compression). We hope XSL fans will enjoy this example; and XSL foes will acknowledge its power! More chess games created by the same stylesheet: Description FO Source PDF PostScript Fischer-Euwe.xml Fischer-Euwe.fo Fischer-Euwe.pdf Fischer-Euwe.ps Robert Fischer - Max Euwe Fischer-Tal.xml Fischer-Tal.fo Fischer-Tal.pdf Fischer-Tal.ps Robert Fischer - Mikhail Tal Kasparov-Karpov.xml Kasparov-Karpov.fo Kasparov-Karpov.pdf Kasparov-Karpov.ps Garry Kasparov - Anatoly Karpov Note: We have used an unabridged chess notation; the original PGN data are even more concise.We know it is possible to process even the short chess notation by XSL, and gladly leave this exercise to volunteers . -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING!

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING! Maurice JANUARY 2015 & Ashley Amy Lee’s Bold Experiment FineLine Technologies JN Index 80% 1.5 BWR PU JANUARY A USCF Publication $5.95 01 GM Wesley So and a friendly spectator hold up his winner’s check. 7 25274 64631 9 IFC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:28 AM Page 1 SLCC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:50 AM Page 1 The Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis is preparing for another fantastic year! 2015 U.S. Championship 2015 U.S. Women’s Championship 2015 U.S. Junior Closed $10K Saint Louis Open GM/IM Title Norm Invitational 2015 Sinquefi eld Cup $10K Thanksgiving Open www.saintlouischessclub.org 4657 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 | (314) 361–CHESS (2437) | [email protected] NON-DISCRIMINATION POLICY: The CCSCSL admits students of any race, color, nationality, or ethnic origin. THE UNEXPECTED COLLISION OF CHESS AND HIP HOP CULTURE 2&72%(5r$35,/2015 4652 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 (314) 367-WCHF (9243) | worldchesshof.org Photo © Patrick Lanham Financial assistance for this project With support from the has been provided by the Missouri Regional Arts Commission Arts Council, a state agency. CL_01-2014_masthead_JP_r1_chess life 12/10/2014 10:30 AM Page 2 Chess Life EDITORIAL STAFF Chess Life Editor and Daniel Lucas [email protected] Director of Publications Chess Life Online Editor Jennifer Shahade [email protected] Chess Life for Kids Editor Glenn Petersen [email protected] Senior Art Director Frankie Butler [email protected] Editorial Assistant/Copy Editor Alan Kantor [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jo Anne Fatherly [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jennifer Pearson [email protected] Technical Editor Ron Burnett TLA/Advertising Joan DuBois [email protected] USCF STAFF Executive Director Jean Hoffman ext. -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

My Best Games of Chess, 1908-1937, 1927, 552 Pages, Alexander Alekhine, 0486249417, 9780486249414, Dover Publications, 1927

My Best Games of Chess, 1908-1937, 1927, 552 pages, Alexander Alekhine, 0486249417, 9780486249414, Dover Publications, 1927 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1OiqRxa http://goo.gl/RTzNX http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=My+Best+Games+of+Chess%2C+1908-1937 One of chess's great inventive geniuses presents his 220 best games, with fascinating personal accounts of the dazzling victories that made him a legend. Includes historic matches against Capablanca, Euwe, and Bogoljubov. Alekhine's penetrating commentary on strategy, tactics, and more — and a revealing memoir. Numerous diagrams. DOWNLOAD http://t.co/6HPUQSukXD http://ebookbrowsee.net/bv/My-Best-Games-of-Chess-1908-1937 http://bit.ly/1haFYcA Games played in the world's Championship match between Alexander Alekhin (holder of the title) and E. D. Bogoljubow (challenger) , Frederick Dewhurst Yates, Alexander Alekhine, Efim Dmitrievich Bogoljubow, W. Winter, 1930, World Chess Championship, 48 pages. Championship chess , Philip Walsingham Sergeant, Jan 1, 1963, Games, 257 pages. Alexander Alekhine's Best Games , Alexander Alekhine, Conel Hugh O'Donel Alexander, John Nunn, 1996, Games, 302 pages. This guide features Alekhine's annotations of his own games. It examines games that span his career from his early encounters with Lasker, Tarrasch and Rubenstein, through his. From My Games, 1920-1937 , Max Euwe, 1939, Chess, 232 pages. Masters of the chess board , Richard Réti, 1958, Games, 211 pages. The book of the Nottingham International Chess Tournament 10th to 28th August, 1936. Containing all the games in the Master's Tournament and a small selection of games from the Minor Tournament with annotations and analysis by Dr. -

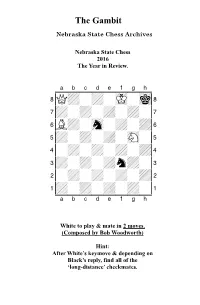

2016 Year in Review

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future. -

Dutchman Who Did Not Drink Beer. He Also Surprised My Wife Nina by Showing up with Flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital Just Before She Gave Birth to My Son Mitchell

168 The Bobby Fischer I Knew and Other Stories Dutchman who did not drink beer. He also surprised my wife Nina by showing up with flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital just before she gave birth to my son Mitchell. I hadn't said peep, but he had his quiet ways of finding out. Max was quiet in another way. He never discussed his heroism during the Nazi occupation. Yet not only did he write letters to Alekhine asking the latter to intercede on behalf of the Dutch martyrs, Dr. Gerard Oskam and Salo Landau, he also put his life or at least his liberty on the line for several others. I learned of one instance from Max's friend, Hans Kmoch, the famous in-house annotator at AI Horowitz's Chess Review. Hans was living at the time on Central Park West somewhere in the Eighties. His wife Trudy, a Jew, had constant nightmares about her interrogations and beatings in Holland by the Nazis. Hans had little money, and Trudy spent much of the day in bed screaming. Enter Nina. My wife was working in the New York City welfare system and managed to get them part-time assistance. Hans then confided in me about how Dr. E greased palms and used his in fluence to save Trudy's life by keeping her out of a concentration camp. But mind you, I heard this from Hans, not from Dr. E, who was always Max the mum about his good deeds. Mr. President In 1970, Max Euwe was elected president of FIDE, a position he held until 1978. -

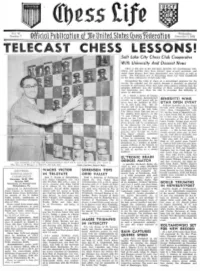

Telecast Chess Lessons!

USCF Vol. VI Wednesday, Number 7 offj clal Publication of The Unltecl States (bess federati on December 5, 1951 TELECAST CHES S LESSONS! Salt Lake City Chess Club Cooperates 'With University And Deseret News Chess is not new to the television channels, for simultancous exhi· bilions anti m a tches have lx'Cn telecast upon sevcral occasions, and nol(.."(] chess pl ayers havc becn interviewed ovcr telcvision as well as r adio. But someUliJlg new in telecasting chess ha:; been wntributed by the che:;s cnthusiasts o( Sail Lake City. RCCOt,.'llizing the value of chess as a I'eereutional program for the invalid, the crippkod and thc shut-in beeause it demands no physical cxercise 0 1' movement. these Sail Lake chess players realized that the principle difficulty wns the teaching o( thcse scattered individuals. And inspiration gavc them the clue to ovcrcome this difficulty of space by televis ion. As a rcsult a series of lessons in chcss elementals, demonstrated Vi SU:llly on a wall board will be BENEDITTI WINS given over the facilities or KST... UTAH OPEN EVENT TV in So lt Lake City. The in· Will ia m Bc neditli of Las Vegas structor wj\\ be Sam Teitckbaum, Ncv.:I da State Champion, won the Pilst prcsident of the Salt Lake Utah Opcn Championship with City YMCA Chess Club and one or 5-1, culling down all poncnts 11ft· tile ranking local players, 011 the er a first J'4lHnd loss to h'vin Tay· " l J and Culture" PI'OSI'am, pro· lor of Sail Lake City, and obtain duced (0 1' the University of Utah ing possession of the Sam '['eitel· by }tCX. -

La Comprensione Del Gioco

LLOOGGIICCAALL TTHHIINNKKIINNGG di Riccardo Annoni A.S.D. Circolo Scacchistico della Versilia Cari amici scacchisti, l’estate è agli sgoccioli e inizia a salirmi la febbre degli scacchi, dopo qualche mese di digiuno mi ritrovo a salivare per le 64 caselle. Per adesso mi sfogo su Word con questo articoletto [era iniziato così… ora ormai è un libello – n.d.a.] che apro trascrivendo qui sotto un passo del celebre libro “Think Like a Grandmaster” di Alexander Kotov (London, 1971): “When later I was busy writing this book I approached Botvinnik and asked him to tell me what he did when his opponent was thinking. The former world title-holder replied in much the following terms: Basically I do divide my thinking into two parts. When my opponent’s clock is going I discuss general considerations in an internal dialogue with myself. When my own clock is going I analyse concrete variations.” Botvinnik raccomandava di usare il tempo a disposizione dell’avversario per eseguire valutazioni di tipo strategico e posizionale e il nostro tempo per eseguire i necessari calcoli tattici che ci porteranno a giocare la nostra mossa. “Chess is mental torture” – Garry Kasparov Kasparov, che era un allievo di Botvinnik ha probabilmente ereditato questo metodo di pensiero alla scacchiera: considerazioni generali di tipo strategico durante la pensata dell’avversario e calcoli tattici nel proprio tempo. Non c’è mai riposo alla scacchiera, gli Scacchi sono una tortura mentale. Iniziamo a vedere cosa fare quindi Quando scorre il tempo del nostro avversario Valutazione Strategica La Tattica è al servizio della Strategia, ovvero la Tattica implementa la Strategia. -

Botvinnik's Secret Games

Botvinnik's Secret Games Jan Timman MikhaiL Botvinnik was the uItimate boy scout of chess - aIways prepared! Indeed, his advance preparation for his key matches was feared by the greatest. It even invoLved the radio bIaring whi Le he was pLaying training games as weLL as having nicotine-puffing opponents bLow smoke in his eyes during practice games, in order to accIimatise himseLf for the reaL thing. Of course, this was before the days of modern poLiticaL correctness when smoking in pubLic is regarded by the powers- that-be as a heinous crime and is, unLike ticking the highway cLean with your tongue, noh, generat[y banned by taw on heaIth and safety grounds. Botvinnik's training games were a wetI guarded secret onty shared by a few trusty coLteagues, such as the Grandmasters Ragozin, Averbakh and Furman. ttre Soviet state was d monument to paranoia at the best of times, but suspicion mul-tipLied when wortd titLes hinged on secrecy, and these games have Lain hidden for decades after they were pLayed. Botvinnik was Wortd Champion three times, from 1948- 1957, 1958 -1964 and 1961 -1963. His finaL championship victory against Tat in the 1961 revenge match counts as one of the highest scoring rating performances in the history of chess. It was of course based on the most meticuIous preparation, not Ieast in the psychoIogicaL sphere of seeking to find and ptay positions which were not to TaIrs taste. Grandmaster Jan Timman is one of the most popular and colounfut ptayers on the modern scene. A finatist in the FIDE-tllorLd Chess Federation-tllorLd Chess Championship in 1993, Timman has been the second dominating force in Dutch chess after worLd champion Dr Max Euwe. -

Painter and Writer. Grob Was a Leading Swiss Player from Th

Grob Henry (04.06.1904 - 05.07.1974) Swiss International Master (1950, inauguration year of FIDE titles). Painter and writer. Grob was a leading swiss player from the 1930s to 1950s, and Swiss Champion in 1939 and 1951. Best results: Barcelona 1935, 3rd; Ostende 1936, 2nd, Ostende 1937, 1-3rd (first on tie-break, alongside with Fine and Keres, ahead of Landau, List, Koltanowski, Tartakower, 10 players; tournament winner Grob beat both, Fine and Keres!), Hastings 1947/48, 2nd-4th (Szabo won) He played multiple matches against strong opposition: He lost to Salomon Flohr (1½-4½) in 1933, beat Jacques Mieses (4½-1½) in 1934, drew with George Koltanowski (2-2), lost to Lajos Steiner 3-1 in 1935, lost to Max Euwe (½-5½) in 1947, lost to Miguel Najdorf (1-5) in 1948, lost to Efim Bogoljubow (2½-4½) in 1949 and to Lodewejk Prins (1½-4½) in 1950 (selection of matches). A participant in the Olympiads of 1927, 1935 and 1952. Addict of the opening 1.g4 (Grob’s attack”) which was deeply analysed in his book Angriff published in 1942. During the period 1940-1973, he was the editor of the chess column published in “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”. Author of “Lerne Schach spielen” (Zürich, 1945, reprinted many times). A professional artist, Grob has published Henry Grob the Artist, a book containing portraits of Grandmasters against whom he played (note: Grob writes his prename with an “y”, not an “i”). Famous game: Flohr, Salo - Grob, Henry Arosa match Arosa (1), 1933 1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 c5 3.dxc5 e6 4.e4 Bxc5 5.Bb5+ Nc6 6.exd5 exd5 7.O-O Nge7 8.Nbd2 O-O 9.Nb3 Bd6 -

Price List of TOGO 25 06 2021 Code

TOGO 25 06 2021 Code: TG210233a-TG210250f Newsletter No. 1442 / Issues date: 25.06.2021 Printed: 24.09.2021 / 12:50 Code Country / Name Type EUR/1 Qty TOTAL Stamperija: TG210233a- TOGO 2021 Perforated €4.95 - - silver Alexander Alekhine (Chess Champions - 75th FDC €7.45 - - memorial anniversary of Alexander Alekhine Imperforated €15.00 - - (Alexander Alekhine 1892–1946; José Capablanca FDC imperf. €17.50 - - 1888–1942) [4v 3200 F]) Stamperija: TG210233b- TOGO 2021 Perforated €4.95 - - silver Alexander Alekhine (Chess Champions - 75th FDC €7.45 - - memorial anniversary of Alexander Alekhine Imperforated €15.00 - - (Alexander Alekhine 1892–1946) Background info: FDC imperf. €17.50 - - World chess champion 1927–1935, 1937–1946; Alexandre Alekhine vs. José Raúl Capablanca “The game to end all the games”, World Championship Ma) Stamperija: TG210234a- TOGO 2021 Perforated €4.95 - - silver Emanuel Lasker (Chess Champions - 80th memorial FDC €7.45 - - anniversary of Emanuel Lasker (Emanuel Lasker Imperforated €15.00 - - 1868–1941; Wilhelm Steinitz 1836–1900) [4v 3200 F]) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - Stamperija: TG210234b- TOGO 2021 Perforated €4.95 - - silver Emanuel Lasker (Chess Champions - 80th memorial FDC €7.45 - - anniversary of Emanuel Lasker (Emanuel Lasker Imperforated €15.00 - - 1868–1941) Background info: World chess champion FDC imperf. €17.50 - - 1894–1921; Emanuel Lasker vs. Wilhelm Steinitz "Happily Ever Lasker", World Championship Match (1894) [s/s 3300 F]) Stamperija: TG210235a- TOGO 2021 Perforated €4.95 - - gold José Raúl Capablanca (Chess Champions - 79th FDC €7.45 - - memorial anniversary of José Raúl Capablanca (José Imperforated €15.00 - - Capablanca 1888–1942; Emanuel Lasker 1868–1941) FDC imperf. €17.50 - - [4v 3200 F]) Stamperija: TG210235a- TOGO 2021 Perforated €4.95 - - silver José Raúl Capablanca (Chess Champions - 79th FDC €7.45 - - memorial anniversary of José Raúl Capablanca (José Imperforated €15.00 - - Capablanca 1888–1942; Emanuel Lasker 1868–1941) FDC imperf.