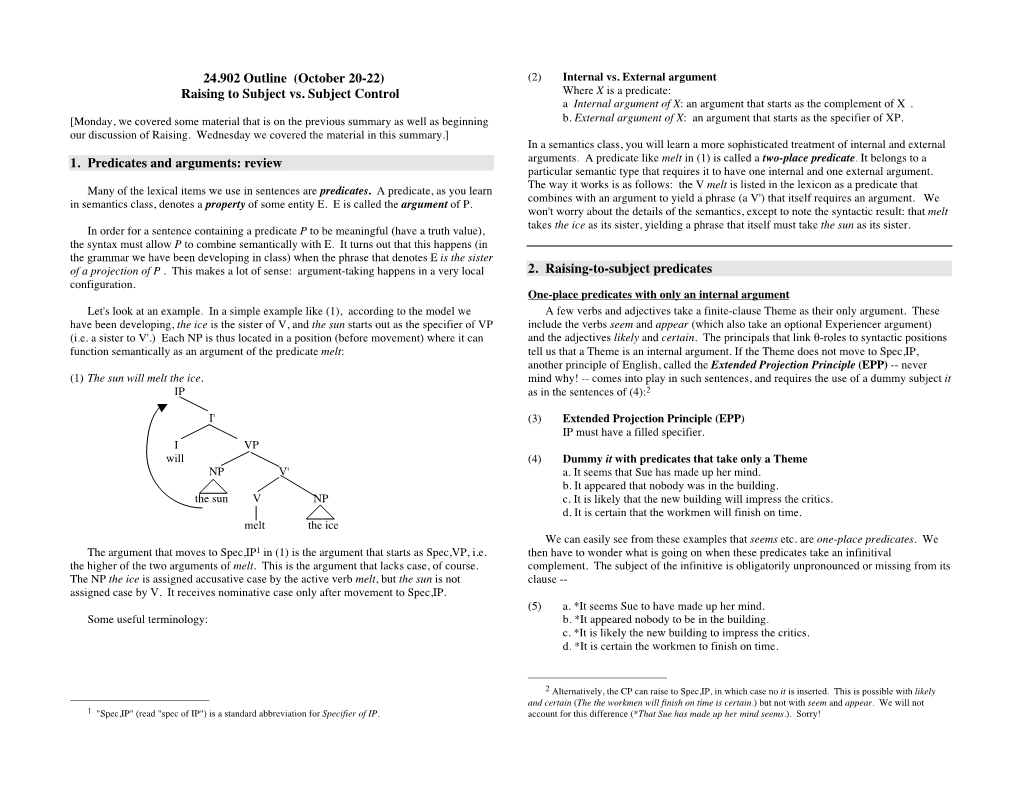

Raising to Subject Vs. Subject Control 1. Predicates and Arguments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Root Modality and Thematic Relations in Tagalog and English*

Proceedings of SALT 26: 775–794, 2016 On root modality and thematic relations in Tagalog and English* Maayan Abenina-Adar Nikos Angelopoulos UCLA UCLA Abstract The literature on modality discusses how context and grammar interact to produce different flavors of necessity primarily in connection with functional modals e.g., English auxiliaries. In contrast, the grammatical properties of lexical modals (i.e., thematic verbs) are less understood. In this paper, we use the Tagalog necessity modal kailangan and English need as a case study in the syntax-semantics of lexical modals. Kailangan and need enter two structures, which we call ‘thematic’ and ‘impersonal’. We show that when they establish a thematic dependency with a subject, they express necessity in light of this subject’s priorities, and in the absence of an overt thematic subject, they express necessity in light of priorities endorsed by the speaker. To account for this, we propose a single lexical entry for kailangan / need that uniformly selects for a ‘needer’ argument. In thematic constructions, the needer is the overt subject, and in impersonal constructions, it is an implicit speaker-bound pronoun. Keywords: modality, thematic relations, Tagalog, syntax-semantics interface 1 Introduction In this paper, we observe that English need and its Tagalog counterpart, kailangan, express two different types of necessity depending on the syntactic structure they enter. We show that thematic constructions like (1) express necessities in light of priorities of the thematic subject, i.e., John, whereas impersonal constructions like (2) express necessities in light of priorities of the speaker. (1) John needs there to be food left over. -

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Chapter 12 Control and Raising Anne Abeillé Université De Paris

Chapter 12 Control and Raising Anne Abeillé Université de Paris The distinction between raising and control predicates has been a hallmark of syn- tactic theory since Rosenbaum (1967), Postal (1974). Contrary to transformational analyses, HPSG treats the difference as mainly a semantic one: raising verbs(seem, begin, expect) do not semantically select their subject (or object) nor assign them a semantic role, while control verbs (want, promise, persuade) semantically select all their syntactic arguments. On the syntactic side, raising verbs share their subject (or object) with the subject of their non-finite complement while control verbs only coindex them Pollard & Sag (1994). We will provide creole data (from Mauritian) which support a phrasal analysis of their complement, and argue against a clausal (or small clause) analysis (Henri & Laurens (2011). The distinction is also relevant for non-verbal predicates such as adjectives (likely vs eager). The raising analysis naturally extends to copular constructions (become, consider) and auxiliary verbs (Pollard & Sag 1994; Sag et al. 2020). 1 The distinction between raising and control predicates 1.1 The main distinction between raising and control verbs In a broad sense ’control’ refers to a relation of referential dependence between an unexpressed subject (the controlled element) and an expressed or unexpressed constituent (the controller); the referential properties of the controlled element, including possibly the property of having no reference at all, are determined by those of the controller (Bresnan 1982: 372). Verbs taking non-finite complements usually determine the interpretation of the missing subject of the non-finite verb. With want, the subject is understood as the subject of the infinitive, while with persuade it is the object, as shown by the reflexives (1a), (1b). -

Expanding the Scope of Control and Raising∗

1 Expanding the scope of control and raising∗ Maria Polinsky and Eric Potsdam University of California at San Diego and University of Florida 1. Introduction The relationship between linguistic theory and empirical data is a proverbial two-way street, but it is not uncommon for the traffic in that street to move only in one direction. The study of raising and control is one such case, where the empirical lane has been running the risk of becoming too empty, and much theorizing has been done on the basis of English and similar languages. A statement in a recent paper is quite telling in that regard: “Our impression from the literature … is that control behaves cross-linguistically in much the same fashion [as in English]…” (Jackendoff and Culicover 2003: 519). If indeed all languages structure control in ways similar to English, cross-linguistic investigation might not be expected to have much to offer, so there has not been much impetus for pursuing them. This paper offers a new incentive to pursue empirical data on control and raising. For these phenomena, recent results from both theoretical and empirical work have coalesced in a promising way allowing us to expand the boundaries of a familiar concept. This in turn provides a stronger motivation for the development of raising/control typologies. 2. Innovations in linguistic theory and their consequence for control and raising Two main innovations in linguistic theory allow us to predict a greater range of variation in control and raising: the unification of control and raising under a single analysis as movement and the compositional view of movement. -

Malagasy Extraposition: Evidence for PF Movement

Nat Lang Linguist Theory https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-021-09505-2 Malagasy extraposition Evidence for PF movement Eric Potsdam1 Received: 28 August 2018 / Accepted: 23 January 2021 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature B.V. part of Springer Nature 2021 Abstract Extraposition is the non-canonical placement of dependents in a right- peripheral position in a clause. The Austronesian language Malagasy has basic VOXS word order, however, extraposition leads to VOSX. Extraposed constituents behave syntactically as though they were in their undisplaced position inside the predicate at both LF and Spell Out. This paper argues that extraposition is achieved via movement at Phonological Form (PF). I argue against alternatives that would derive extraposi- tion with syntactic A’ movement or stranding analyses. Within a Minimalist model of grammar, movement operations take place on the branch from Spell Out to PF and have only phonological consequences. Keywords Malagasy · Extraposition · Movement · Phonological Form · Word order 1 Introduction Extraposition—the non-canonical placement of certain constituents in a right- peripheral position—has been investigated in detail in only a small number of lan- guages. There is a considerable literature for English, SOV Germanic languages Ger- man and Dutch, and the SOV language Hindi-Urdu. The construction has not been widely explored in other, typologically distinct languages. This lacuna means that we have probably not seen the full range of options and have also not tested pro- posed analyses in the widest possible way. The goal of this paper is to investigate in some detail extraposition in Malagasy, an Austronesian language with basic VOXS word order spoken by approximately 17 million people on the island of Madagascar. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Predicative Possessives, Relational Nouns, and Floating Quantifiers

REMARKS AND REPLIES 825 Predicative Possessives, Relational Nouns, and Floating Quantifiers George Tsoulas Rebecca Woods Green (1971) notes the apparent unacceptability of certain quantifica- tional expressions as possessors of singular head nouns. We provide data from a range of English dialects to show that such constructions are not straightforwardly unacceptable, but there are a number of re- strictions on their use. We build on Kayne’s (1993, 1994) analysis of English possessives in conjunction with considerations on floating quantifiers to explain both the types of possessive that are permitted in the relevant dialects and their distribution, which is restricted to predicative position. Keywords: floating quantifiers, possessives, predication 1 Introduction Green (1971:601) makes the following observation (numbering adjusted): The noun phrases of (1): (1) a. One of my friends’ mother b. All of their scarf c. Both of our scarf d. One of our scarf e. Both of my sisters’ birthday [my sisters are twins] which should be well-formed paraphrases of (2): (2) a. The mother of one of my friends b. The scarf that belongs to all of them c. The scarf that belongs to both of us d. The scarf of one of us e. The birthday of both of my sisters are ungrammatical. Portions of earlier versions of this article have been presented at the EDiSyn European Dialect Syntax Workshop VII (Konstanz, 2013) and in research seminars in York and Berlin (ZAS). We are indebted to those audiences for their comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank the following colleagues for discussion, suggestions, and criticism that led to many improvements: Josef Bayer, Gennaro Chierchia, Patrick Elliott, Kyle Johnson, Kook-Hee Gil, Nino Grillo, Richard Kayne, Margarita Makri, David Pesetsky, Bernadette Plunkett, Uli Sauerland, Peter Sells, Sten Vikner, Norman Yeo, and Eytan Zweig. -

Corpus Study of Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Diglossic Speech in Cairene Arabic

CORPUS STUDY OF TENSE, ASPECT, AND MODALITY IN DIGLOSSIC SPEECH IN CAIRENE ARABIC BY OLA AHMED MOSHREF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, Chair Professor Eyamba Bokamba Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Assistant Professor Marina Terkourafi ABSTRACT Morpho-syntactic features of Modern Standard Arabic mix intricately with those of Egyptian Colloquial Arabic in ordinary speech. I study the lexical, phonological and syntactic features of verb phrase morphemes and constituents in different tenses, aspects, moods. A corpus of over 3000 phrases was collected from religious, political/economic and sports interviews on four Egyptian satellite TV channels. The computational analysis of the data shows that systematic and content morphemes from both varieties of Arabic combine in principled ways. Syntactic considerations play a critical role with regard to the frequency and direction of code-switching between the negative marker, subject, or complement on one hand and the verb on the other. Morph-syntactic constraints regulate different types of discourse but more formal topics may exhibit more mixing between Colloquial aspect or future markers and Standard verbs. ii To the One Arab Dream that will come true inshaa’ Allah! عربية أنا.. أميت دمها خري الدماء.. كما يقول أيب الشاعر العراقي: بدر شاكر السياب Arab I am.. My nation’s blood is the finest.. As my father says Iraqi Poet: Badr Shaker Elsayyab iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’m sincerely thankful to my advisor Prof. Elabbas Benmamoun, who during the six years of my study at UIUC was always kind, caring and supportive on the personal and academic levels. -

1 Noun Classes and Classifiers, Semantics of Alexandra Y

1 Noun classes and classifiers, semantics of Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, Melbourne Abstract Almost all languages have some grammatical means for the linguistic categorization of noun referents. Noun categorization devices range from the lexical numeral classifiers of South-East Asia to the highly grammaticalized noun classes and genders in African and Indo-European languages. Further noun categorization devices include noun classifiers, classifiers in possessive constructions, verbal classifiers, and two rare types: locative and deictic classifiers. Classifiers and noun classes provide a unique insight into how the world is categorized through language in terms of universal semantic parameters involving humanness, animacy, sex, shape, form, consistency, orientation in space, and the functional properties of referents. ABBREVIATIONS: ABS - absolutive; CL - classifier; ERG - ergative; FEM - feminine; LOC – locative; MASC - masculine; SG – singular 2 KEY WORDS: noun classes, genders, classifiers, possessive constructions, shape, form, function, social status, metaphorical extension 3 Almost all languages have some grammatical means for the linguistic categorization of nouns and nominals. The continuum of noun categorization devices covers a range of devices from the lexical numeral classifiers of South-East Asia to the highly grammaticalized gender agreement classes of Indo-European languages. They have a similar semantic basis, and one can develop from the other. They provide a unique insight into how people categorize the world through their language in terms of universal semantic parameters involving humanness, animacy, sex, shape, form, consistency, and functional properties. Noun categorization devices are morphemes which occur in surface structures under specifiable conditions, and denote some salient perceived or imputed characteristics of the entity to which an associated noun refers (Allan 1977: 285). -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Higher-Order Grammatical Features in Multilingual BERT Isabel Papadimitriou Ethan A

Deep Subjecthood: Higher-Order Grammatical Features in Multilingual BERT Isabel Papadimitriou Ethan A. Chi Stanford University Stanford University [email protected] [email protected] Richard Futrell Kyle Mahowald University of California, Irvine University of California, Santa Barbara [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We investigate how Multilingual BERT (mBERT) encodes grammar by examining how the high-order grammatical feature of morphosyntactic alignment (how different languages define what counts as a “subject”) is manifested across the embedding spaces of different languages. To understand if and how morphosyntactic alignment affects contextual embedding spaces, we train classifiers to recover the subjecthood of mBERT embeddings in transitive sentences (which do not contain overt information about morphosyntactic alignment) and then evaluate Figure 1: Top: Illustration of the difference between them zero-shot on intransitive sentences alignment systems. A (for agent) is notation used for (where subjecthood classification depends on the transitive subject, and O for the transitive ob- alignment), within and across languages. We ject:“The lawyer chased the dog.” S denotes the find that the resulting classifier distributions intransitive subject: “The lawyer laughed.” The blue reflect the morphosyntactic alignment of their circle indicates which roles are marked as “subject” in training languages. Our results demonstrate each system. that mBERT representations are influenced by Bottom: Illustration of the training and test process. high-level grammatical features that are not We train a classifier to distinguish A from O arguments manifested in any one input sentence, and that using the BERT contextual embeddings, and test the this is robust across languages. Further ex- classifier’s behavior on intransitive subjects (S).