Process and Impact of Niels Bohr's Visit to Japan and China in 1937: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Group of the Committee for the Publication of Hantaro Nagaoka's Biography

Research Group of the Committee for the Publication of Hantaro Nagaoka's Biography Eri Yagi* The Research Group, whose members are Dr. Kiyonobu Itakura of the Na tional Institute for Education Research, Mr. Tosaku Kimura of the National Science Museum, and myself, has completed a biography of Hantaro Nagaoka, which will be published soon (in Japanese) by the Asahi Newspaper Publisher in Tokyo. The Research Group was organized by the Committee in 1963. It was just after the special exhibition of Nagaoka's science activities, held at the National Science Museum in Tokyo by the support of the History of Science Society of Japan. The Committee has been directed by Professor Yoshio Fujioka, who had learned physics under Nagaoka. Unpublished materials, e.g., Nagaoka's notebooks, diaries, corespondences, photos were generosly donated to the National Science Museum by the family of Nagaoka. In addition, those who had been in contact with Nagaoka kindly con tributed informations to the Research Group. The above materials and informations have been arranged, cataloged, and examined by the Research Group. Hantaro Nagaoka was bom at Nagasaki prefecture in the southern part of Japan in 1865 and died in Tokyo in 1950. He was primarily responsible for pro moting the advancement of physics in Japan, between 1900 and 1925, as a professor at the Department of Physics, the University of Tokyo. In the earlier period before Nagaoka started his researches, such local studies as the properties of Japanese magic mirrors, earthquakes, and geomagnetism had dominated by the influence of foreign teachers in Japan. In addition to the study of atomic structure, Nagaoka covered varied fields in physics as magnetostriction, geophysics, mathematical physics, spectroscopy, and radio waves. -

The Early History of the Niels Bohr Institute

CHAPTER 4.1 Birthplace of a new physics - the early history of the Niels Bohr Institute Peter Robertson* Abstract SCI.DAN.M. The foundation in 1921 of the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen was to prove an important event in the I birth of modern physics. From its modest beginnings as • ONE a small three-storey building and a handful of physicists, HUNDRED the Institute underwent a rapid expansion over the fol lowing years. Under Bohr’s leadership, the Institute provided the principal centre for the emergence of quan YEARS tum mechanics and a new understanding of Nature at OF the atomic level. Over sixty physicists from 17 countries THE came to collaborate with the Danish physicists at the In BOHR stitute during its first decade. The Bohr Institute was the ATOM: first truly international centre in physics and, indeed, one of the first in any area of science. The Institute pro PROCEEDINGS vided a striking demonstration of the value of interna tional cooperation in science and it inspired the later development of similar centres elsewhere in Europe and FROM the United States. In this article I will discuss the origins and early development of the Institute and examine the A CONFERENCE reasons why it became such an important centre in the development of modern physics. Keywords: Niels Bohr Institute; development of quan tum mechanics; international cooperation in science. * School of Physics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic. 3010, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 481 PETER ROBERTSON SCI.DAN.M. I 1. Planning and construction of the Institute In 1916 Niels Bohr returned home to Copenhagen over four years since his first visit to Cambridge, England, and two years after a second visit to Manchester, working in the group led by Ernest Ru therford. -

Models of the Atom

David Sang Models of the atom Today we are very familiar with the picture of the atom as a particle with a tiny nucleus at its centre and a cloud of electrons orbiting around the nucleus. But where did this model come from? What were scientists trying to explain using their models of the atom? To find out, we have to go back to the early years of the twentieth century. A model of the atom. But does the nucleus glow like this? No. And are electrons blue? No. Discovering radioactivity and the electron By the 1890s, most physicists were convinced that matter was made up of atoms. The idea of vast In this photo, an electron beam is bent along a circular path by a magnetic field. numbers of tiny, moving particles could explain The beam is produced at the bottom in an ‘electron gun’ and follows a clockwise many things, including the behaviour of gases and path inside the evacuated tube. A small amount of gas has been left in the tube; the differences between the chemical elements. this glows to show up the path of the beam. Then, in 1896, Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity. He was investigating uranium salts, The importance of these two discoveries was that many of which glow in the dark. To his surprise, he they suggested that atoms were not indestructible. Key words Atoms are tiny but they are made of still smaller found that all the uranium-containing substances model that he tested produced invisible radiation that particles. could blacken photographic paper. -

Otto Stern Annalen 4.11.11

(To be published by Annalen der Physik in December 2011) Otto Stern (1888-1969): The founding father of experimental atomic physics J. Peter Toennies,1 Horst Schmidt-Böcking,2 Bretislav Friedrich,3 Julian C.A. Lower2 1Max-Planck-Institut für Dynamik und Selbstorganisation Bunsenstrasse 10, 37073 Göttingen 2Institut für Kernphysik, Goethe Universität Frankfurt Max-von-Laue-Strasse 1, 60438 Frankfurt 3Fritz-Haber-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft Faradayweg 4-6, 14195 Berlin Keywords History of Science, Atomic Physics, Quantum Physics, Stern- Gerlach experiment, molecular beams, space quantization, magnetic dipole moments of nucleons, diffraction of matter waves, Nobel Prizes, University of Zurich, University of Frankfurt, University of Rostock, University of Hamburg, Carnegie Institute. We review the work and life of Otto Stern who developed the molecular beam technique and with its aid laid the foundations of experimental atomic physics. Among the key results of his research are: the experimental test of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of molecular velocities (1920), experimental demonstration of space quantization of angular momentum (1922), diffraction of matter waves comprised of atoms and molecules by crystals (1931) and the determination of the magnetic dipole moments of the proton and deuteron (1933). 1 Introduction Short lists of the pioneers of quantum mechanics featured in textbooks and historical accounts alike typically include the names of Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Arnold Sommerfeld, Niels Bohr, Max von Laue, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Paul Dirac, Max Born, and Wolfgang Pauli on the theory side, and of Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Ernest Rutherford, Arthur Compton, and James Franck on the experimental side. However, the records in the Archive of the Nobel Foundation as well as scientific correspondence, oral-history accounts and scientometric evidence suggest that at least one more name should be added to the list: that of the “experimenting theorist” Otto Stern. -

Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 4 May 17th, 9:00 AM - May 19th, 5:00 PM Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science Joseph Little Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Little, Joseph, "Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science" (2001). OSSA Conference Archive. 75. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA4/papersandcommentaries/75 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science1 Author: Joseph Little Response to this paper by: Mark Weinstein © 2001 Joseph Little Introduction Few constructs rest more securely upon the foundation of rhetorical theory than the syllogism. Introduced by Aristotle in the fourth century BC, the syllogism provided Athenian orators with structural guidance for constructing valid, deductive arguments in the polis (Aristotle, 1991, 40; Aristotle, 1984a; Aristotle, 1984b). Yet this guidance is not without qualification: Often neglected in modern times is the fact that valid conclusions, for Aristotle, were only expected to follow necessarily from the premises when the audience was comprised of men acting in accordance with orthos logos, or "right reason" (1984c, 1935-36; 1984d, 1766, 1797, 1798, 1808, 1812, 1819). Also neglected in modern times is the fact that Aristotle thought of "right reason" as a developed ability that "comes to us if growth is allowed to proceed regularly" rather than as an innate aspect of human cognition (1984c, 1939-40). -

Bibliography

Bibliography F.H. Attix, Introduction to Radiological Physics and Radiation Dosimetry (John Wiley & Sons, New York, New York, USA, 1986) V. Balashov, Interaction of Particles and Radiation with Matter (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 1997) British Journal of Radiology, Suppl. 25: Central Axis Depth Dose Data for Use in Radiotherapy (British Institute of Radiology, London, UK, 1996) J.R. Cameron, J.G. Skofronick, R.M. Grant, The Physics of the Body, 2nd edn. (Medical Physics Publishing, Madison, WI, 1999) S.R. Cherry, J.A. Sorenson, M.E. Phelps, Physics in Nuclear Medicine, 3rd edn. (Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003) W.H. Cropper, Great Physicists: The Life and Times of Leading Physicists from Galileo to Hawking (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2001) R. Eisberg, R. Resnick, Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, USA, 1985) R.D. Evans, TheAtomicNucleus(Krieger, Malabar, FL USA, 1955) H. Goldstein, C.P. Poole, J.L. Safco, Classical Mechanics, 3rd edn. (Addison Wesley, Boston, MA, USA, 2001) D. Greene, P.C. Williams, Linear Accelerators for Radiation Therapy, 2nd Edition (Institute of Physics Publishing, Bristol, UK, 1997) J. Hale, The Fundamentals of Radiological Science (Thomas Springfield, IL, USA, 1974) W. Heitler, The Quantum Theory of Radiation, 3rd edn. (Dover Publications, New York, 1984) W. Hendee, G.S. Ibbott, Radiation Therapy Physics (Mosby, St. Louis, MO, USA, 1996) W.R. Hendee, E.R. Ritenour, Medical Imaging Physics, 4 edn. (John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, USA, 2002) International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU), Electron Beams with Energies Between 1 and 50 MeV,ICRUReport35(ICRU,Bethesda, MD, USA, 1984) International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU), Stopping Powers for Electrons and Positrons, ICRU Report 37 (ICRU, Bethesda, MD, USA, 1984) 646 Bibliography J.D. -

Spin-Or, Actually: Spin and Quantum Statistics

S´eminaire Poincar´eXI (2007) 1 – 50 S´eminaire Poincar´e SPIN OR, ACTUALLY: SPIN AND QUANTUM STATISTICS∗ J¨urg Fr¨ohlich Theoretical Physics ETH Z¨urich and IHES´ † Abstract. The history of the discovery of electron spin and the Pauli principle and the mathematics of spin and quantum statistics are reviewed. Pauli’s theory of the spinning electron and some of its many applications in mathematics and physics are considered in more detail. The role of the fact that the tree-level gyromagnetic factor of the electron has the value ge = 2 in an analysis of stability (and instability) of matter in arbitrary external magnetic fields is highlighted. Radiative corrections and precision measurements of ge are reviewed. The general connection between spin and statistics, the CPT theorem and the theory of braid statistics, relevant in the theory of the quantum Hall effect, are described. “He who is deficient in the art of selection may, by showing nothing but the truth, produce all the effects of the grossest falsehoods. It perpetually happens that one writer tells less truth than another, merely because he tells more ‘truth’.” (T. Macauley, ‘History’, in Essays, Vol. 1, p 387, Sheldon, NY 1860) Dedicated to the memory of M. Fierz, R. Jost, L. Michel and V. Telegdi, teachers, colleagues, friends. arXiv:0801.2724v3 [math-ph] 29 Feb 2008 ∗Notes prepared with efficient help by K. Schnelli and E. Szabo †Louis-Michel visiting professor at IHES´ / email: [email protected] 2 J. Fr¨ohlich S´eminaire Poincar´e Contents 1 Introduction to ‘Spin’ 3 2 The Discovery of Spin and of Pauli’s Exclusion Principle, Historically Speaking 6 2.1 Zeeman, Thomson and others, and the discovery of the electron....... -

H-Diplo Article Review 20 19

H-Diplo Article Review 20 19 Article Review Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse H-Diplo Web and Production Editor: George Fujii @HDiplo Article Review No. 869 3 July 2019 Walter E. Grunden. “Physicists and ‘Fellow Travelers’: Nuclear Fear, the Red Scare, and Science Policy in Occupied Japan.” Journal of American-East Asian Relations 25:4 (2018): 343-383. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/18765610-02504001. https://hdiplo.org/to/AR869 Review by Dong-Won Kim, Harvard University hree decades have passed since the Berlin Wall collapsed in 1989, and most members of the younger generation now consider the Cold War to be as antique as both the First World War and the Second World War. In an era of global terrorism that shakes every corner of the world regardless of political Tand religious differences, the “red scare” of 1947-1960 can even seem to be unrealistic. Historians’ efforts to reinterpret the Cold War from different and distant perspectives are therefore only natural.1 Likewise, historians of science are now reinterpreting science and technology during the Cold War from new angles: for example, David Kaiser’s 2005 analysis of the unfair treatment of several theoretical physicists in the United States during the early Cold War period differs from the analyses offered by the historians of science in the 1980s and 1990s.2 Walter Grunden’s article, “Physicists and ‘Fellow Travelers’: Nuclear Fear, the Red Scare, and Science Policy in Occupied Japan,” offers a fresh understanding of the Cold War outside the United States. The paper is particularly welcome because it systematically analyzes how both the American Occupation (1945-1952) and 1 Two good examples are John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), and Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A World History (New York: Basic Books, 2017). -

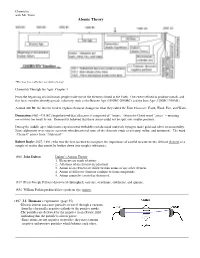

Atomic Theory

Chemistry with Mr. Torre Atomic Theory *The year zero really does not exist in history. Chemistry Through the Ages Chapter 3 From the beginning of civilization people made use of the elements found in the Earth. Ores were refined to produce metals, and this fact is used to identify periods in history, such as the Bronze Age (3500BC-2000BC) and the Iron Age (1200BC-700AD ). Around 400 BC the Greeks tried to explain chemical changes in what they called the Four Elements : Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water. Democritus (460 –371 BC) hypothesized that all matter is composed of “Atoms,” (From the Greek word “ atmos ” – meaning uncuttable) too small to see. Democritus believed that these atoms could not be split into smaller portions. During the middle ages Alchemists experimented with different chemical materials trying to make gold and silver or immortality. Some alchemists were sincere scientists who discovered some of the elements (such as mercury, sulfur, and antimony). The word “Chemist” comes from “Alchemist” Robert Boyle (1627- 1691) who was the first scientist to recognize the importance of careful measurements, defined element as a sample of matter that cannot be broken down into simpler substances. 1800 John Dalton Dalton’s Atomic Theory 1. Elements are made of atoms 2. All atoms of an element are identical 3. Atoms of an element are different than atoms of any other element. 4. Atoms of different elements combine to form compounds. 5. Atoms cannot be created or destroyed. 1817 Pierre Joseph Pelletier discovered chlorophyll, caffeine, strychnine, colchicine, and quinine. 1856 William Perkin produced first synthetic dye, mauve . -

Department of Physics

Department of Physics Department of Physics Department of Physics The Department of Physics at Osaka University offers a world-class education to its undergraduate and graduate students. We have about 50 faculty members, who teach physics to 76 undergraduate students per year in the Physics Department, and over 1000 students in other schools of the university. Our award-winning faculty members perform cutting edge research. As one of the leading universities in Japan, our mission is to serve the people of Japan and the world through education, research, and outreach. The Department of Physics was established in 1931 when Osaka University was founded. The tradition of originality in research was established by the first president of Osaka University, Hantaro Nagaoka, a prominent physicist who proposed a planetary model for atoms before Rutherford’s splitting of the atom. Our former faculty include Hidetsugu Yagi, who invented the Yagi antenna, and Seishi Kikuchi, who demonstrated electron diffraction and also constructed the first cyclotron in Japan. Hideki Yukawa created his meson theory for nuclear forces when he was a lecturer at Osaka University, and later became the first Japanese Nobel laureate. Other prominent professors in recent years include Takeo Nagamiya and Junjiro Kanamori, who established the theory of magnetism, and Ryoyu Uchiyama, who developed gauge theory. The course includes lectures and relevant practical work. Each student joins a research group to pursue a Since then, our department has expanded to cover a course of supervised research on an approved subject wide range of physics, including experimental and in physics. A Master of Science in Physics is awarded theoretical elementary particle and nuclear physics, if a submitted thesis and its oral presentation pass the condensed matter physics, theoretical quantum physics, department’s criteria. -

Newly Opened Correspondence Illuminates Einstein's Personal Life

CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NEWSLETTER Vol. XXXVIII, Number 2 Fall 2006 One Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740-3843, Tel. 301-209-3165 Newly Opened Correspondence Illuminates Einstein’s Personal Life By David C. Cassidy, Hofstra University, with special thanks to Diana Kormos Buchwald, Einstein Papers Project he Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of T Jerusalem recently opened a large collection of Einstein’s personal correspondence from the period 1912 until his death in 1955. The collection consists of nearly 1,400 items. Among them are about 300 letters and cards written by Einstein, pri- marily to his second wife Elsa Einstein, and some 130 letters Einstein received from his closest family members. The col- lection had been in the possession of Einstein’s step-daughter, Margot Einstein, who deposited it with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem with the stipulation that it remain closed for twen- ty years following her death, which occurred on July 8, 1986. The Archives released the materials to public viewing on July 10, 2006. On the same day Princeton University Press released volume 10 of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, con- taining 148 items from the collection through December 1920, along with other newly available correspondence. Later items will appear in future volumes. “These letters”, write the Ein- stein editors, “provide the reader with substantial new source material for the study of Einstein’s personal life and the rela- tionships with his closest family members and friends.” H. Richard Gustafson playing with a guitar to pass the time while monitoring the control room at a Fermilab experiment. -

Otto Stern Annalen 22.9.11

September 22, 2011 Otto Stern (1888-1969): The founding father of experimental atomic physics J. Peter Toennies,1 Horst Schmidt-Böcking,2 Bretislav Friedrich,3 Julian C.A. Lower2 1Max-Planck-Institut für Dynamik und Selbstorganisation Bunsenstrasse 10, 37073 Göttingen 2Institut für Kernphysik, Goethe Universität Frankfurt Max-von-Laue-Strasse 1, 60438 Frankfurt 3Fritz-Haber-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft Faradayweg 4-6, 14195 Berlin Keywords History of Science, Atomic Physics, Quantum Physics, Stern- Gerlach experiment, molecular beams, space quantization, magnetic dipole moments of nucleons, diffraction of matter waves, Nobel Prizes, University of Zurich, University of Frankfurt, University of Rostock, University of Hamburg, Carnegie Institute. We review the work and life of Otto Stern who developed the molecular beam technique and with its aid laid the foundations of experimental atomic physics. Among the key results of his research are: the experimental determination of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of molecular velocities (1920), experimental demonstration of space quantization of angular momentum (1922), diffraction of matter waves comprised of atoms and molecules by crystals (1931) and the determination of the magnetic dipole moments of the proton and deuteron (1933). 1 Introduction Short lists of the pioneers of quantum mechanics featured in textbooks and historical accounts alike typically include the names of Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Arnold Sommerfeld, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Paul Dirac, Max Born, and Wolfgang Pauli on the theory side, and of Konrad Röntgen, Ernest Rutherford, Max von Laue, Arthur Compton, and James Franck on the experimental side. However, the records in the Archive of the Nobel Foundation as well as scientific correspondence, oral-history accounts and scientometric evidence suggest that at least one more name should be added to the list: that of the “experimenting theorist” Otto Stern.