Atomic Modeling in the Early 20Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophical Magazine Vol

Philosophical Magazine Vol. 92, Nos. 1–3, 1–21 January 2012, 353–361 Exploring models of associative memory via cavity quantum electrodynamics Sarang Gopalakrishnana, Benjamin L. Levb and Paul M. Goldbartc* aDepartment of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1110 West Green Street Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; bDepartments of Applied Physics and Physics and E. L. Ginzton Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA; cSchool of Physics, Georgia Institute of Technology, 837 State Street, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA (Received 2 August 2011; final version received 24 October 2011) Photons in multimode optical cavities can be used to mediate tailored interactions between atoms confined in the cavities. For atoms possessing multiple internal (i.e., ‘‘spin’’) states, the spin–spin interactions mediated by the cavity are analogous in structure to the Ruderman–Kittel–Kasuya– Yosida (RKKY) interaction between localized spins in metals. Thus, in particular, it is possible to use atoms in cavities to realize models of frustrated and/or disordered spin systems, including models that can be mapped on to the Hopfield network model and related models of associative memory. We explain how this realization of models of associative memory comes about and discuss ways in which the properties of these models can be probed in a cavity-based setting. Keywords: disordered systems; magnetism; statistical physics; ultracold atoms; neural networks; spin glasses 1. Introductory remarks Since the development of laser cooling and trapping, a -

Research Group of the Committee for the Publication of Hantaro Nagaoka's Biography

Research Group of the Committee for the Publication of Hantaro Nagaoka's Biography Eri Yagi* The Research Group, whose members are Dr. Kiyonobu Itakura of the Na tional Institute for Education Research, Mr. Tosaku Kimura of the National Science Museum, and myself, has completed a biography of Hantaro Nagaoka, which will be published soon (in Japanese) by the Asahi Newspaper Publisher in Tokyo. The Research Group was organized by the Committee in 1963. It was just after the special exhibition of Nagaoka's science activities, held at the National Science Museum in Tokyo by the support of the History of Science Society of Japan. The Committee has been directed by Professor Yoshio Fujioka, who had learned physics under Nagaoka. Unpublished materials, e.g., Nagaoka's notebooks, diaries, corespondences, photos were generosly donated to the National Science Museum by the family of Nagaoka. In addition, those who had been in contact with Nagaoka kindly con tributed informations to the Research Group. The above materials and informations have been arranged, cataloged, and examined by the Research Group. Hantaro Nagaoka was bom at Nagasaki prefecture in the southern part of Japan in 1865 and died in Tokyo in 1950. He was primarily responsible for pro moting the advancement of physics in Japan, between 1900 and 1925, as a professor at the Department of Physics, the University of Tokyo. In the earlier period before Nagaoka started his researches, such local studies as the properties of Japanese magic mirrors, earthquakes, and geomagnetism had dominated by the influence of foreign teachers in Japan. In addition to the study of atomic structure, Nagaoka covered varied fields in physics as magnetostriction, geophysics, mathematical physics, spectroscopy, and radio waves. -

Models of the Atom

David Sang Models of the atom Today we are very familiar with the picture of the atom as a particle with a tiny nucleus at its centre and a cloud of electrons orbiting around the nucleus. But where did this model come from? What were scientists trying to explain using their models of the atom? To find out, we have to go back to the early years of the twentieth century. A model of the atom. But does the nucleus glow like this? No. And are electrons blue? No. Discovering radioactivity and the electron By the 1890s, most physicists were convinced that matter was made up of atoms. The idea of vast In this photo, an electron beam is bent along a circular path by a magnetic field. numbers of tiny, moving particles could explain The beam is produced at the bottom in an ‘electron gun’ and follows a clockwise many things, including the behaviour of gases and path inside the evacuated tube. A small amount of gas has been left in the tube; the differences between the chemical elements. this glows to show up the path of the beam. Then, in 1896, Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity. He was investigating uranium salts, The importance of these two discoveries was that many of which glow in the dark. To his surprise, he they suggested that atoms were not indestructible. Key words Atoms are tiny but they are made of still smaller found that all the uranium-containing substances model that he tested produced invisible radiation that particles. could blacken photographic paper. -

The Discovery of Thermodynamics

Philosophical Magazine ISSN: 1478-6435 (Print) 1478-6443 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tphm20 The discovery of thermodynamics Peter Weinberger To cite this article: Peter Weinberger (2013) The discovery of thermodynamics, Philosophical Magazine, 93:20, 2576-2612, DOI: 10.1080/14786435.2013.784402 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14786435.2013.784402 Published online: 09 Apr 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 658 Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tphm20 Philosophical Magazine, 2013 Vol. 93, No. 20, 2576–2612, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786435.2013.784402 COMMENTARY The discovery of thermodynamics Peter Weinberger∗ Center for Computational Nanoscience, Seilerstätte 10/21, A1010 Vienna, Austria (Received 21 December 2012; final version received 6 March 2013) Based on the idea that a scientific journal is also an “agora” (Greek: market place) for the exchange of ideas and scientific concepts, the history of thermodynamics between 1800 and 1910 as documented in the Philosophical Magazine Archives is uncovered. Famous scientists such as Joule, Thomson (Lord Kelvin), Clau- sius, Maxwell or Boltzmann shared this forum. Not always in the most friendly manner. It is interesting to find out, how difficult it was to describe in a scientific (mathematical) language a phenomenon like “heat”, to see, how long it took to arrive at one of the fundamental principles in physics: entropy. Scientific progress started from the simple rule of Boyle and Mariotte dating from the late eighteenth century and arrived in the twentieth century with the concept of probabilities. -

Philosophical Magazine Atomic-Resolution Spectroscopic

This article was downloaded by: [Cornell University Library] On: 30 April 2015, At: 08:23 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Philosophical Magazine Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tphm20 Atomic-resolution spectroscopic imaging of oxide interfaces L. Fitting Kourkoutis a , H.L. Xin b , T. Higuchi c , Y. Hotta c d , J.H. Lee e f , Y. Hikita c , D.G. Schlom e , H.Y. Hwang c g & D.A. Muller a h a School of Applied and Engineering Physics , Cornell University , Ithaca, USA b Department of Physics , Cornell University , Ithaca, USA c Department of Advanced Materials Science , University of Tokyo , Kashiwa, Japan d Correlated Electron Research Group , RIKEN , Saitama, Japan e Department of Materials Science and Engineering , Cornell University , Ithaca, USA f Department of Materials Science and Engineering , Pennsylvania State University , University Park, USA g Japan Science and Technology Agency , Kawaguchi, Japan h Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science , Ithaca, USA Published online: 20 Oct 2010. To cite this article: L. Fitting Kourkoutis , H.L. Xin , T. Higuchi , Y. Hotta , J.H. Lee , Y. Hikita , D.G. Schlom , H.Y. Hwang & D.A. Muller (2010) Atomic-resolution spectroscopic imaging of oxide interfaces, Philosophical Magazine, 90:35-36, 4731-4749, DOI: 10.1080/14786435.2010.518983 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786435.2010.518983 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. -

Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 4 May 17th, 9:00 AM - May 19th, 5:00 PM Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science Joseph Little Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Little, Joseph, "Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science" (2001). OSSA Conference Archive. 75. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA4/papersandcommentaries/75 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Culturally Inherited Cognitive Activity: Implications for the Rhetoric of Science1 Author: Joseph Little Response to this paper by: Mark Weinstein © 2001 Joseph Little Introduction Few constructs rest more securely upon the foundation of rhetorical theory than the syllogism. Introduced by Aristotle in the fourth century BC, the syllogism provided Athenian orators with structural guidance for constructing valid, deductive arguments in the polis (Aristotle, 1991, 40; Aristotle, 1984a; Aristotle, 1984b). Yet this guidance is not without qualification: Often neglected in modern times is the fact that valid conclusions, for Aristotle, were only expected to follow necessarily from the premises when the audience was comprised of men acting in accordance with orthos logos, or "right reason" (1984c, 1935-36; 1984d, 1766, 1797, 1798, 1808, 1812, 1819). Also neglected in modern times is the fact that Aristotle thought of "right reason" as a developed ability that "comes to us if growth is allowed to proceed regularly" rather than as an innate aspect of human cognition (1984c, 1939-40). -

Spin-Or, Actually: Spin and Quantum Statistics

S´eminaire Poincar´eXI (2007) 1 – 50 S´eminaire Poincar´e SPIN OR, ACTUALLY: SPIN AND QUANTUM STATISTICS∗ J¨urg Fr¨ohlich Theoretical Physics ETH Z¨urich and IHES´ † Abstract. The history of the discovery of electron spin and the Pauli principle and the mathematics of spin and quantum statistics are reviewed. Pauli’s theory of the spinning electron and some of its many applications in mathematics and physics are considered in more detail. The role of the fact that the tree-level gyromagnetic factor of the electron has the value ge = 2 in an analysis of stability (and instability) of matter in arbitrary external magnetic fields is highlighted. Radiative corrections and precision measurements of ge are reviewed. The general connection between spin and statistics, the CPT theorem and the theory of braid statistics, relevant in the theory of the quantum Hall effect, are described. “He who is deficient in the art of selection may, by showing nothing but the truth, produce all the effects of the grossest falsehoods. It perpetually happens that one writer tells less truth than another, merely because he tells more ‘truth’.” (T. Macauley, ‘History’, in Essays, Vol. 1, p 387, Sheldon, NY 1860) Dedicated to the memory of M. Fierz, R. Jost, L. Michel and V. Telegdi, teachers, colleagues, friends. arXiv:0801.2724v3 [math-ph] 29 Feb 2008 ∗Notes prepared with efficient help by K. Schnelli and E. Szabo †Louis-Michel visiting professor at IHES´ / email: [email protected] 2 J. Fr¨ohlich S´eminaire Poincar´e Contents 1 Introduction to ‘Spin’ 3 2 The Discovery of Spin and of Pauli’s Exclusion Principle, Historically Speaking 6 2.1 Zeeman, Thomson and others, and the discovery of the electron....... -

![1 Humphry Davy to John Davy, 15 October [1811] Davy, Collected Letters, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0736/1-humphry-davy-to-john-davy-15-october-1811-davy-collected-letters-vol-1740736.webp)

1 Humphry Davy to John Davy, 15 October [1811] Davy, Collected Letters, Vol

1 Humphry Davy: Analogy, Priority, and the “true philosopher” Sharon Ruston Lancaster University, England https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3864-7382 This essay explores how Davy fashioned himself as, what he called in his poetry, a “true philosopher.” He defined the “true philosopher” as someone who eschewed monetary gain for his scientific work, preferring instead to give knowledge freely for the public good, and as someone working at a higher level than the mere experimentalist. Specifically, Davy presented himself as using the method of analogy to reach his discoveries and emphasised that he understood the “principle” behind his findings. He portrayed himself as one who perceived analogies because he had a wider perspective on the world than many others in his society. The poem in which he describes the “true philosopher” offers us Davy’s private view of this character; the essay then demonstrates how Davy attempted to depict his own character in this way during critical moments in his career. Introduction During the safety lamp controversy of 1815–1817, Humphry Davy deliberately presented himself as a natural philosopher. For Davy this meant someone with a wider purview than others, who is alive to the metaphorical, literary, and philosophical ramifications of his scientific discoveries. He represented himself as working at a highly theoretical level in the laboratory, rather than practically in the mine, making a clear distinction between himself and George Stephenson in this regard. Davy suggested that he was working for loftier ideals and was opposed to monetary gain or profit by patent. He declared that his discoveries were the product of analogical thinking and a consequence of his understanding of scientific principle. -

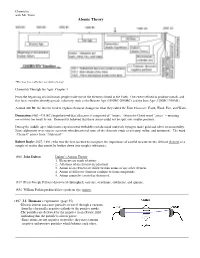

Atomic Theory

Chemistry with Mr. Torre Atomic Theory *The year zero really does not exist in history. Chemistry Through the Ages Chapter 3 From the beginning of civilization people made use of the elements found in the Earth. Ores were refined to produce metals, and this fact is used to identify periods in history, such as the Bronze Age (3500BC-2000BC) and the Iron Age (1200BC-700AD ). Around 400 BC the Greeks tried to explain chemical changes in what they called the Four Elements : Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water. Democritus (460 –371 BC) hypothesized that all matter is composed of “Atoms,” (From the Greek word “ atmos ” – meaning uncuttable) too small to see. Democritus believed that these atoms could not be split into smaller portions. During the middle ages Alchemists experimented with different chemical materials trying to make gold and silver or immortality. Some alchemists were sincere scientists who discovered some of the elements (such as mercury, sulfur, and antimony). The word “Chemist” comes from “Alchemist” Robert Boyle (1627- 1691) who was the first scientist to recognize the importance of careful measurements, defined element as a sample of matter that cannot be broken down into simpler substances. 1800 John Dalton Dalton’s Atomic Theory 1. Elements are made of atoms 2. All atoms of an element are identical 3. Atoms of an element are different than atoms of any other element. 4. Atoms of different elements combine to form compounds. 5. Atoms cannot be created or destroyed. 1817 Pierre Joseph Pelletier discovered chlorophyll, caffeine, strychnine, colchicine, and quinine. 1856 William Perkin produced first synthetic dye, mauve . -

Department of Physics

Department of Physics Department of Physics Department of Physics The Department of Physics at Osaka University offers a world-class education to its undergraduate and graduate students. We have about 50 faculty members, who teach physics to 76 undergraduate students per year in the Physics Department, and over 1000 students in other schools of the university. Our award-winning faculty members perform cutting edge research. As one of the leading universities in Japan, our mission is to serve the people of Japan and the world through education, research, and outreach. The Department of Physics was established in 1931 when Osaka University was founded. The tradition of originality in research was established by the first president of Osaka University, Hantaro Nagaoka, a prominent physicist who proposed a planetary model for atoms before Rutherford’s splitting of the atom. Our former faculty include Hidetsugu Yagi, who invented the Yagi antenna, and Seishi Kikuchi, who demonstrated electron diffraction and also constructed the first cyclotron in Japan. Hideki Yukawa created his meson theory for nuclear forces when he was a lecturer at Osaka University, and later became the first Japanese Nobel laureate. Other prominent professors in recent years include Takeo Nagamiya and Junjiro Kanamori, who established the theory of magnetism, and Ryoyu Uchiyama, who developed gauge theory. The course includes lectures and relevant practical work. Each student joins a research group to pursue a Since then, our department has expanded to cover a course of supervised research on an approved subject wide range of physics, including experimental and in physics. A Master of Science in Physics is awarded theoretical elementary particle and nuclear physics, if a submitted thesis and its oral presentation pass the condensed matter physics, theoretical quantum physics, department’s criteria. -

Research Group of the Committee for the Publication of Hantaro Nagaoka's Biography

Research Group of the Committee for the Publication of Hantaro Nagaoka's Biography Eri Yagi* The Research Group, whose members are Dr. Kiyonobu Itakura of the Na tional Institute for Education Research, Mr. Tosaku Kimura of the National Science Museum, and myself, has completed a biography of Hantaro Nagaoka, which will be published soon (in Japanese) by the Asahi Newspaper Publisher in Tokyo. The Research Group was organized by the Committee in 1963. It was just after the special exhibition of Nagaoka's science activities, held at the National Science Museum in Tokyo by the support of the History of Science Society of Japan. The Committee has been directed by Professor Yoshio Fujioka, who had learned physics under Nagaoka. Unpublished materials, e.g., Nagaoka's notebooks, diaries, corespondences, photos were generosly donated to the National Science Museum by the family of Nagaoka. In addition, those who had been in contact with Nagaoka kindly con tributed informations to the Research Group. The above materials and informations have been arranged, cataloged, and examined by the Research Group. Hantaro Nagaoka was bom at Nagasaki prefecture in the southern part of Japan in 1865 and died in Tokyo in 1950. He was primarily responsible for pro moting the advancement of physics in Japan, between 1900 and 1925, as a professor at the Department of Physics, the University of Tokyo. In the earlier period before Nagaoka started his researches, such local studies as the properties of Japanese magic mirrors, earthquakes, and geomagnetism had dominated by the influence of foreign teachers in Japan. In addition to the study of atomic structure, Nagaoka covered varied fields in physics as magnetostriction, geophysics, mathematical physics, spectroscopy, and radio waves. -

Photon: New Light on an Old Name

1 Photon: New light on an old name Helge Kragh Abstract: After G. N. Lewis (1875-1946) proposed the term “photon” in 1926, many physicists adopted it as a more apt name for Einstein’s light quantum. However, Lewis’ photon was a concept of a very different kind, something few physicists knew or cared about. It turns out that Lewis’ name was not quite the neologism that it has usually been assumed to be. The same name was proposed or used earlier, apparently independently, by at least four scientists. Three of the four early proposals were related to physiology or visual perception, and only one to quantum physics. Priority belongs to the American physicist and psychologist L. T. Troland (1889-1932), who coined the word in 1916, and five years later it was independently introduced by the Irish physicist J. Joly (1857-1933). Then in 1925 a French physiologist, René Wurmser (1890-1993), wrote about the photon, and in July 1926 his compatriot, the physicist F. Wolfers (ca. 1890-1971), did the same in the context of optical physics. None of the four pre-Lewis versions of “photon” was well known and they were soon forgotten. 1. Introduction Ever since the late 1920s, to physicists the term “photon” has just been an apt synonym for the light quantum that Einstein introduced in 1905. Although “light quantum” is still in use, today it is far more common to speak and write about “photon.” The name is derived from Greek (φώτο = photo = light) and the “-on” at the end of the word indicates that the photon is an elementary particle belonging to the same class as the proton, the electron and the neutron.