Monopoly and Monopsony Power in a Market for Mud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Contest Schedule 27, 2019

State Contest Schedule 27, 2019 Last Name First Name Entry # Title Time Building Room Division Category Abou- Mao Zedong and the Chinese Dahech Mohammad 18019 Revolution (2535) 10:45AM University 218 Junior Group Website The Black Death: The Fall of Catholicism and The Rise of JIE - Team Individual Acosta Kimberly 15026 Humanism (1539) 10:45AM Field House C Junior Exhibit Adams Abigail 16012 Tyrus Wong (1507) 11:45AM Field House B Junior Group Exhibit Mamie Till Mobley: A Powerful Mother Turning Her Son's Tragic Death into a Group Adams Isaac 22001 Life of Triumph (2537) 9:00AM Merrick 203 Senior Documentary Individual Adams Jaylin 27003 The Black Panther Party (1515) 9:45AM Elliott 011 Senior Website Individual Aichele Kemery 27006 The Mormon Migration (2541) 9:30AM Elliott 011 Senior Website Mary Anning: She Sells Seashells by the Seashore and Takes Science by Individual Alleman Sophia 11008 Storm (1553) 11:20AM Merrick 201 Junior Documentary Gray Group Allen Joseph 14016 Elizabeth Hamilton (1507) 10:50AM University Chapel Junior Performance Salem witch trials, innocent lives are Individual Alley Malaya 17014 lost (2509) 9:45AM Elliott 001 Junior Website Abyssinia: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cleveland Women Working in the Alonge Sophie 20017 Steel Industry during WWII (2528) 10:45AM University 203B Senior Paper Garrett Morgan: The Cleveland Individual Amos Isaac 17020 Waterworks Rescue (1533) 11:30AM Elliott 001 Junior Website 1 State Contest Schedule 27, 2019 Last Name First Name Entry # Title Time Building Room Division Category SIE - Team Individual Anderson Michael 25010 John Glenn Orbits Earth (2544) 10:45AM Field House A Senior Exhibit Amelia Earhart: Triumphant Aviator JGE Team Angle Hannah 16031 and Her Tragic Disappearance (1545) 11:00AM Field House C Junior Group Exhibit Archuleta Gabriella 18012 Loving V. -

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes Kevin McDonald 1. introduction this: It happens every spring. The perennial hopefulness of opening day leads to talk of LEVEL ONE: “Justice Holmes baseball, which these days means the business ruled that baseball was a sport, not a of baseball - dollars and contracts. And business.” whether the latest topic is a labor dispute, al- LEVEL TWO: “Justice Holmes held leged “collusion” by owners, or a franchise that personal services, like sports and considering a move to a new city, you eventu- law and medicine, were not ‘trade or ally find yourself explaining to someone - commerce’ within the meaning of the rather sheepishly - that baseball is “exempt” Sherman Act like manufacturing. That from the antitrust laws. view has been overruled by later In response to the incredulous question cases, but the exemption for baseball (“Just how did that happen?”), the customary remains.” explanation is: “Well, the famous Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. decided that baseball was exempt from the antitrust laws in a case called The truly dogged questioner points out Federal Baseball Club ofBaltimore 1.: National that Holmes retired some time ago. How can we League of Professional Baseball Clubs,‘ and have a baseball exemption now, when the an- it’s still the law.” If the questioner persists by nual salary for any pitcher who can win fifteen asking the basis for the Great Dissenter’s edict, games is approaching the Gross National Prod- the most common responses depend on one’s uct of Guam? You might then explain that the level of antitrust expertise, but usually go like issue was not raised again in the courts until JOURNAL 1998, VOL. -

Muehlebach Field Dedication July 3, 1923

[page 1] Muehlebach Field Dedication July 3, 1923 Compliments KANSAS CITY BASEBALL CLUB AMERICAN ASSOCIATION [page 2] Proclamation HEY, red-blooded Americans, Fans, EVERYBODY! A new park, Muehlebach Field, dedicated to the great American sport, Baseball, will open Tuesday, July third, Brooklyn Avenue at 22nd. This event will be of interest to all who enjoy clean, healthful, outdoor recreation. The day has gone by when business men look upon a holiday as a lost opportunity. It is now considered an INVESTMENT, as employer and employe alike return, not only with renewed ambition, but with new thoughts and new ideas for which Old Man Success is always on the lookout. For this reason, I recommend that every employer forget the ever present serious side of life and attend the opening baseball game at Muehlebach Field. I also recommend that every employer as far as possible give the same privilege to his employes. To set the example for this recommendation, and to demonstrate its practicality, I declare Tuesday afternoon, July third, a half holiday for all City Hall Employes, beginning at Twelve o’clock (noon). (Signed) FRANK H. CROMWELL, Mayor. -2- [page 3] Program DEDICATORY ADDRESS THOS. J. HICKEY PRESIDENT AMERICAN ASSOCIATION RESPONSE GEO. E. MUEHLEBACH PRESIDENT KANSAS CITY BASEBALL CLUB “KANSAS” GOVERNOR JONATHAN M. DAVIS “MISSOURI” GOVERNOR ARTHUR M. HYDE “KANSAS CITY, MO.” MAYOR FRANK H. CROMWELL Who Will Pitch (Throw) the First Ball “KANSAS CITY, KANSAS" MAYOR W. W. GORDON Who Will Catch? the First Ball FLAG CEREMONY The Stars and Stripes will be raised for the first time over Muehlebach Field BALL GAME 3 P. -

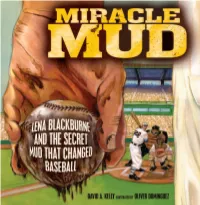

Lena Blackburne's Baseball Rubbing Mud

Lena Blackburne's Baseball Rubbing Mud Lena Blackburne's Baseball Rubbing Mud: balm to ball players everywhere. Back in 1938, a Philadelphia Athletics coach named Lena Blackburne began mixing various batches of mud and water to create a substance that would dull the surface of glossy new baseballs, making them easier to grip. And, of course, it had to work without breaking the rules of baseball. Umpires had previously tried shoe polish, tobacco juice and the dirt beneath their feet to fix the balls, but while these substances did, indeed, dull the balls' surfaces, they also damaged the baseballs in the process. Blackburne's eventual concoction -- crafted from rich mud found in southern New Jersey near the Delaware River (at his favorite fishing hole, to be exact) -- didn't wreck the balls. The Athletics' chief umpire gave it a thumbs-up, and soon other American League teams began clamoring for some. National League teams followed suit, and soon Lena Blackburne's Rubbing Mud was famous Since Blackburne had no kids to inherit his business, he passed it on to a childhood friend, whose grandson, Jim Bintliff, now runs the company. Bintliff says every Major League Baseball team uses the product today, and he makes five or six trips to the mud hole annually to fulfill demand. But he won't say exactly where the revered mud hole is. "The mud is on public land, but we've always kept the location a secret to keep people from trampling it" Joy in Mudville MLB teams can't get enough of Lena Blackburne's secret substance. -

Standings Compiled by Secretary the Third Out

1 ■— — « —— ■ ■■ ■ —— been torn out, and a new aidawalk 3 WALKS PLUS 3 is being put in. < Cardinals Headed Toward * * * Both these store spares are also Pennant; Pitching TUNNEY NEARS being remodeled, and the Broad- EDINBURG ON Men's way Shop, owned by Ben HITS ONE was And Best In Avers Vessels EQUAL Epstein, and which damaged by Batting League * *. * fire several weeks ago, is to be re- opened soon. Lf FLAYING TOP IN UPPER RUN —PROF. HUG TRAINING END _ 17.—(A*—The Edcouch Go NEW YORK. July McAllen, Cleveland Indians have demon- Champ to Box and Eat Up As Donna and strated how a team can make three safe hits and receive three bases Great Quantities I _ Pharr Lose on balls in one inning and still Of Meat Out of score only one run. \ankees Snap this bracket— The Indians performed Upper feat for the benefit of SPECULATOR. N. Y. July 17.— Slump Taking Two; Team W. L. Prt. strange metropolian fans watching them a rest from all Edinburg 9 3 .750 (/Fb—After 24-hour lose both ends if a double-header Cards Emerge After McAllen 7 5 .583 ring work. Gene Tunney decided to to the New York Yankees yester- Donna 7 6 .538 renew exchanging blows with his Losing Pair Edcouch 5 7 .417 day. sparring partners today to fit him- In the third of the first Pharr 2 11 .153 inning self for his world's heavyweight title Lind to right and BY HERBERT W. BARKER Lower bracket— game, singled bout against Tom Hceney on July 26. -

Camp Next Year

. —-—------ -r. u u j The BROWNSVILLE HERALD SPORTS SECTION m?l Weatherbound Pirates Plan Texas Camp Next Year fj to at •*£;’*<&** M. % SEGRAVE RACES 231.3 M.P.H. Bears ■ ■ •»»--• -- — — —— — ^-— — +***-**^ m m m m ~i r*- r^j^nj-n _n_r Here ruxj^ru-lj-ij-u-1Aru~Ln^,-^u-ij-i,nj-_n_r-- j~i_i-i_- nfir -i_i-i_n_~_r_~ Meet A S SHUTOUT; Appear _-Ljn_ru~ijn^_-_i~ur-i_^i_n_ri_r‘T_inri_-Vn_r Tonight SOLONS GOLF; Home; Other Teams Expected to Seal Hampered By Rains Fate of Ball MERSKYSOLD n Loop DALLAS, March 12.—(JP)—San list is Gene Walker, secured In The stage is set—the delegates organization on a professional basis ^ORT MYERS, Fla., March 12 — Antonio's 1929 Bears, minus only trade from Beaumont last fall. He are coming—and a baseball league are optimistic regarding the for- Stinging under the 6 to 0 shut- Mulvey, Grimes and Tate—and two has been “under the weather’’ and of some proportions, may be per- mation of a Class D league. or three possible additions yet to his doctor has advised him to take manently formed tonight. The meeting is scheduled to get T»jt they were given by the Phila- be made to the roster—go to San things easy. William T. (Billy) Burnett, Rio under way at 8 o’clock tonight. Cin- ^^1'lphia Athletics Sunday, the Antonio from Laredo today for the At Corsicana, a workout in the Grande Valley manager of the ’cinnati Reds rolled into Fort My- first home exhibition game of the Y. -

Rivista Dell'arbitrato 1-15

ISSN 1122-0147 ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA PER L’ARBITRATO Pubblicazione trimestrale Anno XXV - N. 1/2015 Poste Italiane s.p.a. - Spedizione in a.p. D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. 1, comma 1, DCB (VARESE) RIVISTA DELL’ARBITRATO diretta da Antonio Briguglio - Giorgio De Nova - Andrea Giardina ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA PER L’ARBITRATO Pubblicazione trimestrale Anno XXV - N. 1/2015 Poste Italiane s.p.a. - Spedizione in a.p. D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. 1, comma 1, DCB (VARESE) RIVISTA DELL’ARBITRATO diretta da Antonio Briguglio - Giorgio De Nova - Andrea Giardina comitato scientifico GUIDO ALPA - FERRUCCIO AULETTA - PIERO BERNARDINI - PAOLO BIAVATI - MAURO BOVE - FEDERICO CARPI - CLAUDIO CONSOLO - DIEGO CORAPI - FABRIZIO CRISCUOLO - GIORGIO GAJA - FRANCESCO PAOLO LUISO - RICCARDO LUZZATTO - NICOLA PICARDI - CARMINE PUNZI - LUCA RADICATI DI BROZOLO - PIETRO RESCIGNO - GIORGIO SACERDOTI - LAURA SALVANESCHI - FERRUCCIO TOMMASEO - ROMANO VACCARELLA - GIOVANNI VERDE - VINCENZO VIGORITI - ATTILIO ZIMATORE. già diretta da ELIO FAZZALARI. direzione: ANTONIO BRIGUGLIO - GIORGIO DE NOVA - ANDREA GIARDINA. MARIA BEATRICE DELI (direttore responsabile). redazione ANDREA BANDINI - LAURA BERGAMINI - ALDO BERLINGUER - ANDREA CARLEVARIS - CLAUDIO CECCHELLA - MASSIMO COCCIA - ALESSANDRA COLOSIMO - ELENA D’ALESSANDRO - ANNA DE LUCA - FERDINANDO EMANUELE - ALESSANDRO FUSILLO - DANTE GROSSI - MAURO LONGO - ROBERTO MARENGO † - FABRIZIO MARRELLA - ELENA OCCHIPINTI - ANDREW G. PATON - FRANCESCA PIETRANGELI ROBERTO VACCARELLA Segretari di redazione: ANDREA ATTERITANO - MARIANGELA ZUMPANO. La Direzione e la Redazione della Rivista hanno sede presso l’Associazio- ne Italiana per l’Arbitrato, in Roma, Via Barnaba Oriani, 34 (c.a.p. 00197) tel. 06/42014749 - 06/42014665; fax 06/4882677; www.arbitratoaia.org e-mail: [email protected] L’Amministrazione ha sede presso la Casa Editrice, in Milano (c.a.p. -

M Ir Aclemudm Ir Aclemud

Kelly Dominguez DAVID A. KELLY grew up an hour away from Cooperstown, New York, home of the Baseball Hall of Fame. Although he looked forward to the Hall’s yearly induction ceremony, his Little League baseball career (right fielder, miserable batting average) made it clear he was never going to be the one inducted. Instead, he decided to focus more on homework than home runs and grew up to become a writer. He now lives in Newton, Massachusetts, about 15 minutes away from Boston’s Fenway Park, LENA BLACKBURNE loved baseball. with his wife Alice, sons Steven and Scott (who are He watched it, he played it, he coached the good baseball players in the family), and a dog WHAT’S THE SECRET TO THE named Samantha. it. But he didn’t love the ways players broke in new baseballs. Tired of soggy, MIRACLE OLIVER DOMINGUEZ was born and raised on PERFECT BASEBALL? YOU JUST MIRACLE the south side of Miami, where he read comics, blackened, stinky baseballs, he found watched cartoons, and played sports with his NEED A LITTLE MUD . a better way. Thanks to a well-timed dad. He spent many hours playing baseball in fishing trip and a top-secret mud recipe, front of his house with his friends. Dominguez received his BFA in illustration from Ringling Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing College of Art + Design. His work takes inspiration MUD Mud was born. For seventy five years, from American illustrators such as Howard Pyle, baseball teams have used Lena’s magic N.C. Wyeth, and J.C. -

September 2010 Prices Realized

HUGGINS & SCOTT SEPT 29-30, 2010 PRICES REALIZED Lot # Title Bids Sale Price 1 1933 R338 Goudey Sport Kings Complete Uncut Sheet (24 Cards) Featuring Ruth, Cobb, Thorpe and Grange 20 $38,187.50 2 1911 T212 Obak Full Uncut Sheet of (179) Cards with (3) Buck Weaver 20 $18,800.00 3 1916 Collins-McCarthy #82 Joe Jackson - SGC 50 24 $14,100.00 4 (42) 1911 T205 Gold Border SGC 40-70 Graded Cards with (4) Hall of Famers 16 $1,880.00 5 (26) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA & SGC Graded Cards with (3) Hall of Famers 11 $1,116.25 6 1911 D304 Brunners Bread Rube Marquard PSA 3 2 $940.00 7 1909-11 E90-1 American Caramel Addie Joss (Portrait) SGC 70 26 $3,231.25 8 1909-11 E90-1 American Caramel Sam Crawford SGC 70 6 $646.25 9 1909 E92 Croft’s Cocoa Cy Young SGC 40 13 $940.00 10 1909 E95 Philadelphia Caramel Christy Mathewson SGC 40 12 $763.75 11 1908 PC800 Vignette Postcards Camnitz & Moeller—Both SGC 40 2 $381.88 12 1910 PC 796 Sepia Postcards Ty Cobb SGC 30 22 $1,997.50 13 1910-11 M116 Sporting Life Tris Speaker SGC 60 18 $1,057.50 14 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets Howie Camnitz SGC 70—Highest Graded 16 $763.75 15 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #33 Jake Pfeister SGC 70—Highest Graded 15 $558.13 16 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #82 Kitty Bransfield SGC 60—Highest Graded 10 $558.13 17 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #113 Bugs Raymond SGC 60—Highest Graded 10 $558.13 18 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #2 Bill Bergen SGC 60—Highest Graded 14 $528.75 19 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #90 Mickey Doolan SGC 50 2 $323.13 20 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets -

Oral Presentations 2020 AANS Annual Scientific Meeting Boston, Massachusetts • April 25–29, 2020

AANS 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts Oral Presentations 2020 AANS Annual Scientific Meeting Boston, Massachusetts • April 25–29, 2020 (DOI: 10.3171/2020.4.JNS.AANS2020abstracts) Disclaimer: The Journal of Neurosurgery Publishing Group (JNSPG) acknowledges that the preceding abstracts are published as submitted and did not go through JNSPG’s peer-review or editing process. 100: Gum Chewing to Expedite Return of Bowel Function after Anterior Lumbar Surgery Alexandra Richards, DNP (Phoenix, AZ); JoDee Winter, PA-C; Naresh Patel, MD; Matthew Neal, MD; Chandan Krishna, MD; Pelagia Kouloumberis; Maziyar Kalani, MD Introduction: Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) is used to treat lumbar spondylosis and spondylolisthesis. The operation involves an anterior, retroperitoneal approach to the spine. Patients frequently experience a slow return of bowel function secondary to anesthetic time, opioid use, and primarily due to the bowel displacement intraoperatively; however, this operation is amenable to outpatient surgery. Gum chewing decreases the time for return to bowel function (RBF) in postoperative colorectal and gynecology patients. Despite this data, the association between gum chewing and RBF has only been studied in posterior spine patients. Methods: Preoperative patients needing one or two level ALIF were recruited at a single institution. Patients were selected based on inclusion criteria and randomized by a random number generator; a blinded research assistant assisted with randomization. The experimental group (gum-chewing) and control group (hospital standard management) were compared with the endpoints of length of stay, length to return of bowel function via the passing of flatus and passing of stool. Medical care was standardized with regard to pain control, diet, ambulation, and deep venous thrombus prophylactic and perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. -

Probak Is New in Estate Vs

D-2 SPORTS. THE EVENING STAR, WASHINGTON. I). C., THURSDAY. JANUARY 16. 1930. SPORTS. - ~ ¦¦¦¦ '¦ "¦ , -| '' ' ' ' ' 1 ’ Goslin Remains Nationals Big Punch : Bowling Fans Pulling for Billheimer I | rTilccc!laneouß A. L. Records, 1929 CAMPBELL SWEEPSTAKES Nats Get Young Hitter; BRADDOCK TO BE HEAVY QUINTERO BATTLES Boss Accepts Contract AFTER LOMSKI BATTLE BATS OVER 91 Washington is getting some new RUNS CHICAGO, January 16 (4*).—James CLUB RECORDS. Koenig, New York ~ll* 23 1 41 17 Shires, 100 32 1 41 30 talent for trial in the South in the Jersey light- *.l, H.B.P.- SO Chicago J. Braddock, rugged New Hale, .. 40 HAS FOLLOWING Philadelphia 101 12 3 ]j LEADER Spring. The latest addition to the Detroit Ml l* 496 31 1 39 24 heavyweight, will join the heavyweight Philadelphia 843 440 Kerr. Chicago 137 Nationals is Nelson J. Jester, a ranks after his 10-round engagement New 2f L. Sewell. Cleveland.. 1?4 29 0 39 26 York *94 25 518 Rhyne. 25 4 38 14 Assassin, Cleveland 453 16 363 Boston 120 strapping youngster who resides on with Leo Lomski, the Aberdeen Morgan. ..93 37 2 38 24 DRAW TO Maryland. TO Washington 4a* Cleveland MANDELL the Eastern Shore of He at the Chicago Coliseum 858 17 tomorrow GRIFFIN ... LEAD 0 37 28 in Hoffman, Chicago 107 34 Finishing Ruck Two St. Louis *l9 22 431 129 128 3 36 44 Confidence Unshaken After caught and played around the Infield night. Chicago 425 22 43* Bishop. Phlla Schang, ... 94 74 7 36 32 Chlneoteague Boston 413 38 494 St. -

The Role of Media in the Development of Professional Baseball in New York from 1919-1929

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Crashsmith Dope: the Role of Media in the Development of Professional Baseball in New York From 1919-1929 Ryan McGregor Whittington Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Whittington, Ryan McGregor, "Crashsmith Dope: the Role of Media in the Development of Professional Baseball in New York From 1919-1929" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 308. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/308 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRASHSMITH DOPE: THE ROLE OF MEDIA IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL IN NEW YORK FROM 1919-1929 BY RYAN M. WHITTINGTON B.A., University of Mississippi, Oxford, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The University of Mississippi In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Meek School of Journalism © Copyright by Ryan M. Whittington 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT John McGraw’s New York Giants were the premier team of the Deadball Era, which stretched from 1900-1919. Led by McGraw and his ace pitcher, Christy Mathewson, the Giants epitomized the Deadball Era with their strong pitching and hard-nosed style of play. In 1919 however, The New York Times and The Sporting News chronicled a surge in the number of home runs that would continue through the 1920s until the entire sport embraced a new era of baseball.