Otto Von Bismarck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

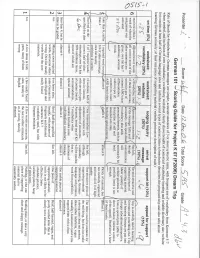

A+ Grade Project

og(s^-l -0 N l-trr ? 6 a: 5F / q\ P P € x o F-.;3 "Afi o \ B:-: * + o o-o.6:l : ac= E =i,;, 5 ;34: 2: 93: u | { eP.99a 5 g -?a6333:;:.3-r \ a=t 1? i^+ 9of;A 3: -: i c f ;- P -= = ? 4Bio o : 99:9 !r \J+'e : 5.. - 1:-=.92 A !.. - 6 0 0 =Y (n *9 'r F* !- 3S1* 9l : a 9-i =: la=.938s.yI i i " -?: I -; +d; i =? -e s'c'H< ^i 9 =i6!18 i:9-4i q'k 63= {[s a;;i tE1r CI' = = o ; a: i i d'isEai'; €FfrE f r 5- \an ;?!>RSO = = dE < F . > *i:3-:1F 6;g39:-;i: e-a 2 ggHei i i a E r. < =! - o o 6E3: € E -: a;.i: +igBE-Hi:i its3; =id-_?c1 : i q a3 € As ^=. Fa1i:* B6 o q'.3 Ir ld P = -1aP 6 = 1l*ae3*: 'qF4'+=€ =az= a a jo .9; IN ;eB Ei4EiZF :9l"J" P! =; E icF=;l c e*;r,! < ed.B. t j- =:; F 1\ :=- 6 A.-\ g N --l Z ;3?=.6Br 6 a =a 9 id -ii ^l x 'A;i55s-:;- 9dii o 2 ; =9F :6 i -o-f o !r -=$3' { U) : -*' \o a-6' 6-. j-:;5 N o g 3P.Z ! F-i:9 * 92I d Ee96 (t) ig,t= 3iAAliF aoi a P \gEFtr€FT q s aqi 5&==;:;' ?6ek I g #: q i E I 7+2'a :.E 6-=_*P o dQ :;g:'! L + &oi o (/\ :," ia _;6= f x i 5 5aE;ie E ; a93.3i 6' E!9 3*iin' t I 9-3 -Ft q 60q; tt o) gL :q3F1g aJ 5"a: (D 994 3! 3 fia;; '!) F?3gfi;:;. -

A Guide for Educators and Students TABLE of CONTENTS

The Munich Secession and America A Guide for Educators and Students TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR EDUCATORS GETTING STARTED 3 ABOUT THE FRYE 3 THE MUNICH SECESSION AND AMERICA 4 FOR STUDENTS WELCOME! 5 EXPERIENCING ART AT THE FRYE 5 A LITTLE CONTEXT 6 MAJOR THEMES 8 SELECTED WORKS AND IN-GALLERY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS The Prisoner 9 Picture Book 1 10 Dutch Courtyard 11 Calm before the Storm 12 The Dancer (Tänzerin) Baladine Klossowska 13 The Botanists 14 The Munich Secession and America January 24–April 12, 2009 SKETCH IT! 15 A Guide for Educators and Students BACK AT SCHOOL 15 The Munich Secession and America is organized by the Frye in GLOSSARY 16 collaboration with the Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, and is curated by Frye Foundation Scholar and Director Emerita of the Museum Villa Stuck, Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker. This self-guide was created by Deborah Sepulvida, the Frye’s manager of student and teacher programs, and teaching artist Chelsea Green. FOR EDUCATORS GETTING STARTED This guide includes a variety of materials designed to help educators and students prepare for their visit to the exhibition The Munich Secession and America, which is on view at the Frye Art Museum, January 24–April 12, 2009. Materials include resources and activities for use before, during, and after visits. The goal of this guide is to challenge students to think critically about what they see and to engage in the process of experiencing and discussing art. It is intended to facilitate students’ personal discoveries about art and is aimed at strengthening the skills that allow students to view art independently. -

Surnames in Europe

DOI: http://dx.doi.org./10.17651/ONOMAST.61.1.9 JUSTYNA B. WALKOWIAK Onomastica LXI/1, 2017 Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu PL ISSN 0078-4648 [email protected] FUNCTION WORDS IN SURNAMES — “ALIEN BODIES” IN ANTHROPONYMY (WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO POLAND) K e y w o r d s: multipart surnames, compound surnames, complex surnames, nobiliary particles, function words in surnames INTRODUCTION Surnames in Europe (and in those countries outside Europe whose surnaming patterns have been influenced by European traditions) are mostly conceptualised as single entities, genetically nominal or adjectival. Even if a person bears two or more surnames, they are treated on a par, which may be further emphasized by hyphenation, yielding the phenomenon known as double-barrelled (or even multi-barrelled) surnames. However, this single-entity approach, visible e.g. in official forms, is largely an oversimplification. This becomes more obvious when one remembers such household names as Ludwig van Beethoven, Alexander von Humboldt, Oscar de la Renta, or Olivia de Havilland. Contemporary surnames resulted from long and complicated historical processes. Consequently, certain surnames contain also function words — “alien bodies” in the realm of proper names, in a manner of speaking. Among these words one can distinguish: — prepositions, such as the Portuguese de; Swedish von, af; Dutch bij, onder, ten, ter, van; Italian d’, de, di; German von, zu, etc.; — articles, e.g. Dutch de, het, ’t; Italian l’, la, le, lo — they will interest us here only when used in combination with another category, such as prepositions; — combinations of prepositions and articles/conjunctions, or the contracted forms that evolved from such combinations, such as the Italian del, dello, del- la, dell’, dei, degli, delle; Dutch van de, van der, von der; German von und zu; Portuguese do, dos, da, das; — conjunctions, e.g. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

Its Beginning and Aftermath with a Main Focus on Austria

Journal of Research and Opinion Received 10 June 2020 | Accepted 21 June 2020 | Published Online 25 June 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15520/jro.v7i6.68 JRO 7 (6), 2738−2748 (2020) ISSN (O) 2589-9341 | (P) 2589-9058 IF:2.1 RESEARCH ARTICLE “The Great War”– Its beginning and aftermath with a main focus on Austria ∗ Rainer Feldbacher 1Associate Professor at the School Abstract of History, Capital Normal Many factors played a crucial role in the start of a conflict that the world University, Beijing, China, 100089 had seen as “a war to end all wars”, that started after the assassination of the crown prince in Sarajevo. Initially a European war, soon nations worldwide got involved. With the end of the World War and the beginning of the collapse of the Habsburg Empire, the “Republic of German-Austria” was proclaimed on November 12th, 1918, after the treaty of Saint-Germain 10 September 1919 officially as “First Republic of Austria“. The circumstances opened the door to National Socialism and the much crueler Second World War. Keywords: Austria-Hungary, World War, Habsburg, Fourteen Points, Peace Treaty of Versailles 1 INTRODUCTION – AUSTRIA´S ROLE IN and in most cases having led to Austria´s misfortune, EUROPE and mainly its disastrous way into the First World War.In the 16th century, the Habsburgs became the absburg, the rulers of the Austrian Empire largest Western European Empire since Rome, ini- whose name originated from the building of Hthe Habsburg Castle in Switzerland, built at tially ruling huge regions of that continent. Soon a the Aar, the largest tributary of the High Rhine river, political division between the Spanish and Austrian had been the dynasty with a long history. -

Victories Are Not Enough: Limitations of the German Way of War

VICTORIES ARE NOT ENOUGH: LIMITATIONS OF THE GERMAN WAY OF WAR Samuel J. Newland December 2005 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. This publication is a work of the United States Government, as defined in Title 17, United States Code, section 101. As such, it is in the public domain and under the provisions of Title 17, United States Code, section 105, it may not be copyrighted. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** My sincere thanks to the U.S. Army War College for approving and funding the research for this project. It has given me the opportunity to return to my favorite discipline, Modern German History, and at the same time, develop a monograph which has implications for today’s army and officer corps. In particular, I would like to thank the Dean of the U.S. Army War College, Dr. William Johnsen, for agreeing to this project; the Research Board of the Army War College for approving the funds for the TDY; and my old friend and colleague from the Militärgeschichliches Forschungsamt, Colonel (Dr.) Karl-Heinz Frieser, and some of his staff for their assistance. In addition, I must also thank a good former student of mine, Colonel Pat Cassidy, who during his student year spent a considerable amount of time finding original curricular material on German officer education and making it available to me. -

Otto Von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck Retrato de Otto von Bismarck 1871. Canciller de Alemania 21 de marzo de 1871-20 de marzo de 1890 Monarca Guillermo I (1871-1888) Federico III (1888) Guillermo II (1888-1890) Predecesor Primer Titular Sucesor Leo von Caprivi Primer ministro de Prusia 23 de septiembre de 1862-1 de enero de 1873 Predecesor Adolf zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen Sucesor Albrecht von Roon 9 de noviembre de 1873-20 de marzo de 1890 Predecesor Albrecht von Roon Sucesor Leo von Caprivi Datos personales Nacimiento 1 de abril de 1815 Schönhausen, Prusia Fallecimiento 30 de julio de 1898 (83 años) Friedrichsruh, Alemania Partido sin etiquetar Cónyuge Johanna von Puttkamer Hijos Herbert von Bismarck y Wilhelm von Bismarck Ocupación político, diplomático y jurista Alma máter Universidad de Gotinga Religión luteranismo Firma de Otto von Bismarck [editar datos en Wikidata] Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen, Príncipe de Bismarck y Duque de Lauenburg (Schönhausen, 1 de abrilde 1815–Friedrichsruh, 30 de julio de 1898)1 conocido como Otto von Bismarck, fue un estadista, burócrata, militar, político yprosista alemán, considerado el fundador del Estado alemán moderno. Durante sus últimos años de vida se le apodó el «Canciller de Hierro» por su determinación y mano dura en la gestión de todo lo relacionado con su país,n. 1 que incluía la creación de un sistema de alianzas internacionales que aseguraran la supremacía de Alemania, conocido como el Reich.1 Cursó estudios de leyes y, a partir de 1835, trabajó en los tribunales -

1. Walter B. Douglas Rooster and Chickens, Ca. 1920 1952.038 2

3 22 2 4 21 28 32 1 17 14 10 33 40 8 18 45 19 23 49 29 6 38 24 34 5 43 41 46 51 11 15 36 30 35 25 47 53 7 9 12 13 16 20 26 27 31 37 39 42 44 48 50 52 54 1. Walter B. Douglas 7. Hermann-David Saloman 12. Franz von Defregger 18. Adolf Heinrich Lier 24. Johann Friedrich Voltz 28. Eugéne-Louis Boudin 33. Marie Weber 38. Léon Barillot 44. Charles Soulacroix 50. Emile Van Marcke Rooster and Chickens, ca. 1920 Corrodi The Blonde Bavarian, ca. 1905 Lanscape Near Polling, 1860-70 Cattle on the Shore, ca. 1883 View of the Harbor, Le Havre, Head of a Girl in Fold Costume, Three Cows and a Calf, ca. 1890 Expectation, ca. 1890 In the Marshes, ca. 1880 1952.038 Venice, ca. 1900 1952.034 1952.107 1952.182 1885-90 1870s-1880s 1952.005 1952.158 1952.178 1952.025 1952.010 1952.187 2. Edmund Steppes 13. Ludwig Knaus 19. Friedrich Kaulbach 25. Louis Gabriel Eugéne Isabey 39. William Adolphe Bouguereau 45. Arnold Gorter 51. Nikolai Nikanorovich Dubovskoi The Time of the Cuckoo, 1907 8. Franx-Xaver Hoch Drove of Swine: Evening Effect Portrait of Hanna Ralph, n.d. The Storm, 1850 29. Wilhelm Trüber 34. Henry Raschen The Shepherdess, 1881 Autumn Sun, n.d. Seascape with Figures, 1899 1952.160 Landscape with Church Towers, 1952.085 1952.080 1952.073 Three Fir Trees at Castle Old Man, n.d. 1952.012 1952.056 1952.039 1912 Hemsbach, 1904 1952.139 3. -

WBFSH Eventing Breeder 2020 (Final).Xlsx

LONGINES WBFSH WORLD RANKING LIST - BREEDERS OF EVENTING HORSES (includes validated FEI results from 01/10/2019 to 30/09/2020 WBFSH member studbook validated horses) RANK BREEDER POINTS HORSE (CURRENT NAME / BIRTH NAME) FEI ID BIRTH GENDER STUDBOOK SIRE DAM SIRE 1 J.M SCHURINK, WIJHE (NED) 172 SCUDERIA 1918 DON QUIDAM / DON QUIDAM 105EI33 2008 GELDING KWPN QUIDAM AMETHIST 2 W.H. VAN HOOF, NETERSEL (NED) 142 HERBY / HERBY 106LI67 2012 GELDING KWPN VDL ZIROCCO BLUE OLYMPIC FERRO 3 BUTT FRIEDRICH 134 FRH BUTTS AVEDON / FRH BUTTS AVEDON GER45658 2003 GELDING HANN HERALDIK XX KRONENKRANICH XX 4 PATRICK J KEARNS 131 HORSEWARE WOODCOURT GARRISON / WOODCOURT GARRISON104TB94 2009 MALE ISH GARRISON ROYAL FURISTO 5 ZG MEYER-KULENKAMPFF 129 FISCHERCHIPMUNK FRH / CHIPMUNK FRH 104LS84 2008 GELDING HANN CONTENDRO I HERALDIK XX 6 CAROLYN LANIGAN O'KEEFE 128 IMPERIAL SKY / IMPERIAL SKY 103SD39 2006 MALE ISH PUISSANCE HOROS 7 MME SOPHIE PELISSIER COUTUREAU, GONNEVILLE SUR127 MER TRITON(FRA) FONTAINE / TRITON FONTAINE 104LX44 2007 GELDING SF GENTLEMAN IV NIGHTKO 8 DR.V NATACHA GIMENEZ,M. SEBASTIEN MONTEIL, CRETEIL124 (FRA)TZINGA D'AUZAY / TZINGA D'AUZAY 104CS60 2007 MARE SF NOUMA D'AUZAY MASQUERADER 9 S.C.E.A. DE BELIARD 92410 VILLE D AVRAY (FRA) 122 BIRMANE / BIRMANE 105TP50 2011 MARE SF VARGAS DE STE HERMELLE DIAMANT DE SEMILLY 10 BEZOUW VAN A M.C.M. 116 Z / ALBANO Z 104FF03 2008 GELDING ZANG ASCA BABOUCHE VH GEHUCHT Z 11 A. RIJPMA, LIEVEREN (NED) 112 HAPPY BOY / HAPPY BOY 106CI15 2012 GELDING KWPN INDOCTRO ODERMUS R 12 KERSTIN DREVET 111 TOLEDO DE KERSER -

Masterarbeit / Master´S Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER´S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master´s Thesis „Beyond Late Josephinism: Josephinian Influences and the Commemoration of Emperor Joseph II in the Austrian Kulturkampf (1861-1874)“ verfasst von / submitted by Christos Aliprantis angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2015 / Vienna 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 803 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Geschichte UG2002 degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Lothar Höbelt For my parents and brother 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ___________ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (4) PROLOGUE: I. The Academic Interest on Josephinism: Strenghtenes and Lacunas of the Existing Literature (6) II. Conceptual Issues, Aims, Temporal and Spatial Limits of the Current Study (10) CHAPTER 1: Josephinism and the Afterlife of Joseph II in the early Kulturkampf Era (1861-1863) I. The Afterlife of Joseph II and Josephinism in 1848: Liberal, Conservative and Cleri- cal Interpretations. (15) II. The Downfall of Ecclesiastical Josephinism in Neoabsolutism: the Concordat and the Suppressed pro-Josephinian Reaction against it. (19) III. 1861: The Dawn of a New Era and the Intensified Public Criticism against the Con- cordat. (23) IV. From the 1781 Patent of Tolerance to the 1861 Protestant Patent: The Perception of the Josephinian Policy of Confessional Tolerance. (24) V. History Wars and Josephinism: Political Pamphelts, Popular Apologists and Acade- mic Historiography on Joseph II (1862-1863). (27) CHAPTER 2: Josephinism and the Afterlife of Joseph II during the Struggle for the Confessional Legislation of May 1868 I. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss .