Political Dimension of Policy Implementation in Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

Trends in Owo Traditional Sculptures: 1995 – 2010

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.5 No.1. December 2015 TRENDS IN OWO TRADITIONAL SCULPTURES: 1995 – 2010 Ebenezer Ayodeji Aseniserare Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] 08034734927, 08057784545 and Efemena I. Ononeme Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] [email protected] 08023112353 Abstract This study probes into the origin, style and patronage of the traditional sculptures in Owo kingdom between 1950 and 2010. It examines comparatively the sculpture of the people and its affinity with Benin and Ife before and during the period in question with a view to predicting the future of the sculptural arts of the people in the next few decades. Investigations of the study rely mainly on both oral and written history, observation, interviews and photographic recordings of visuals, visitations to traditional houses and Owo museum, oral interview of some artists and traditionalists among others. Oral data were also employed through unstructured interviews which bothered on analysis, morphology, formalism, elements and features of the forms, techniques and styles of Owo traditional sculptures, their resemblances and relationship with Benin and Ife artefacts which were traced back to the reigns of both Olowo Ojugbelu 1019 AD to Olowo Oshogboye, the Olowo of Owo between 1600 – 1684 AD, who as a prince, lived and was brought up by the Oba of Benin. He cleverly adopted some of Benin‟s sculptural and historical culture and artefacts including carvings, bronze work, metal work, regalia, bead work, drums and some craftsmen with him on his return to Owo to reign. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

Changing Values of Traditional Marriage Among the Awori in Badagry Local Government

International Journal of Social & Management Sciences, Madonna University (IJSMS) Vol.1 No.1, March 2017; pg.131 – 138 CHANGING VALUES OF TRADITIONAL MARRIAGE AMONG THE AWORI IN BADAGRY LOCAL GOVERNMENT OLARINMOYE, ADEYINKA WULEMAT & ALIMI, FUNMILAYO SOFIYAT Department of Sociology, Lagos State University. Email address: [email protected] Abstract Some decades ago, it would have seemed absurd to question the significance of traditional marriage among the Awori-Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria, as it was considered central to the organization of adult life. However, social change has far reaching effects on African traditional life. For instance, the increased social acceptance of pre-marital cohabitation, pre-marital sex and pregnancies and divorce is wide spread among the Yoruba people of today. This however appeared to have replaced the norms of traditional marriage; where marriage is now between two individuals and not families. This research uncovers what marriage values of the Yoruba were and how these values had been influenced overtime. The qualitative method of data collection was used. Data was collected and analyzed utilizing the content analysis and ethnographic summary techniques. The study revealed that modernization, education, mixture of cultures and languages, inter-marriage and electronic media have brought about changes in traditional marriage, along with consequences such as; drop in family standard, marriage instability, weak patriarchy system, and of values and customs. Despite the social changes, marriage remains significant value for individuals, families and in Yoruba society as a whole. Keywords: Traditional values, marriage, social change, Yoruba. INTRODUCTION The practice of marriage is apparently one of the most interesting aspects of human culture. -

Samuel Adekunle Ola Osungbeju

FRIENDSHIP AND BETRAYAL: A NARRATIVE READING OF MATTHEW 26: 47-56 IN THE LIGHT OF THE CONCEPT OF OREODALE OF THE YORUBA PEOPLE IN NIGERIA. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIBLICAL STUDIES IN THE SCHOOL OF RELIGION, PHILOSOPHY AND CLASSICS, UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU-NATAL, PIETERMARITZBURG, SOUTH AFRICA. BY SAMUEL ADEKUNLE OLA OSUNGBEJU 1 ABSTRACT The theme of friendship and betrayal cuts across many disciplines and cultures. This research focuses on the theme of friendship which is fundamentally related to the theme of the church (Matt.16, 18) and love as contained in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt.5-7), and is clearly expressed in Matthew 5:23-26 and 7:12. This theme rings through in Matthew’s Gospel as a narrative or story. This then forms the background to our search for a new understanding of the theme of friendship and betrayal in the Matthean Gospel with a focus on Matt.26:47-56 in light of the socio-cultural perspective of the Yoruba people in Nigeria. Friendship cuts across different societies with its diverse cultural distinctiveness. We find in the Matthean community, a model of friendship as exemplified by Jesus with his disciples as well as with the people of his day that is informed by love, mutual trust, loyalty, commitment, forgiveness, and which revolves around discipleship and equality. Although Jesus took on the role of a servant and friend with his disciples he remained the leader of the group. But his disciples abandoned him at the very critical point of his life with Peter even publicly denying knowing him. -

Private Sector Participation in Water Supply: Prospects and Challenges in Developing Economies

Private Sector Participation in Water Supply: Prospects and Challenges in Developing Economies E.O. Longe*1, M.O. Kehinde*2 and Olajide, C.O3* *1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. [email protected] ; [email protected] *2Environment Agency (Anglian Region) Kingfisher House Goldhay Way Orton Goldhay Peterborough PE2 5ZR, UK [email protected] *3*Lagos Water Corporation, Water House, Ijora, Lagos. ABSTRACT Lagos State Water Corporation (LSWC), a Government agency since 1981 took over the responsibility of providing potable water to the people of Lagos State. However, the challenges facing the corporation continue to mount in the face of increasing demand, expendable water sources and need for injection of funds. In the recent past most developing countries embarked on large-scale infrastructure through public sector financing and control. Reliance on such public sector financing and management however has not proved effective or sustainable while the successes of projects are not guaranteed. Adduced reasons are not far fetched and these ranged from deteriorating fiscal conditions, operational inefficiency, excessive bureaucracy and corruption. Consequently, the need for the private sector participation in public sectors enterprises therefore becomes inevitable in the provision of investment and control. Lagos State Water Corporation programme for Private Sector Participation in potable water supply commenced about thirteen years back. In order to realize this objective a complete due diligence of the corporation was carried out. The technical baseline findings showed that raw water sources yield far exceeded present LSWC capacity, while production capacity is utilized at less than 50% of installed capacity. -

Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 9, No. 4, 2013, pp. 23-29 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020130904.2598 www.cscanada.org Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie Adepeju Oti[a],*; Oyebola Ayeni[b] [a]Ph.D, Née Aderogba. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. [b] INTRODUCTION Ph.D. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. *Corresponding author. Culture refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, Received 16 March 2013; accepted 11 July 2013 hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects Abstract and possessions acquired by a group of people in the The history of colonisation dates back to the 19th course of generations through individual and group Century. Africa and indeed Nigeria could not exercise striving (Hofstede, 1997). It is a collective programming her sovereignty during this period. In fact, the experience of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group of colonisation was a bitter sweet experience for the or category of people from another. The position that continent of Africa and indeed Nigeria, this is because the ideas, meanings, beliefs and values people learn as the same colonialist and explorers who exploited the members of society determines human nature. People are African and Nigerian economy; using it to develop theirs, what they learn, therefore, culture ultimately determine the quality in a person or society that arises from a were the same people who brought western education, concern for what is regarded as excellent in arts, letters, modern health care, writing and recently technology. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

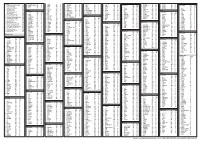

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Curriculum Vitae 01

CURRICULUM VITAE 01. Personal Data: Name: KANUMUANGI Bukola Olayinka Date of birth: 19th July, 1981 Place of birth: Owo Age: 38 Sex: Female Marital status: Married Nationality: Nigerian Town/state of origin: Owo/Ondo State Contact Address: Department of Communication and General Studies, College of Agricultural Management and Rural Development, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta. Phone number: 08060577733 E.mail: [email protected] Present Post and Salary: Assistant Lecturer/CONUASS 02 step 01, 125,773.33 02. Educational Background i. Educational Institutions Attended Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State 2017 till date Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State 2013-2015 Nigerian Teachers Institute, Kaduna (Abeokuta learning center) 2013 Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State. 2008-2011 Le Village Français du Nigéria, Badagry, Lagos State. 2007 Ipenmen Community Grammar School, Owo. 1994-2001 St Thomas Primary School, Owo. 1987-1994 ii. Educational Qualifications PhD in progress Masters Degree 2017 Post-Graduate Diploma in Education: 2017 Bachelor of Arts in French: 2012 Diploma in French: 2007 West African Senior School Certificate: 2001 Primary School Leaving Certificate: 1994 03. Working Experience French Teacher at Lyceum Montessori School: 2013 - 2014 Administrative Officer at Surgicare Consult: 2011- 2017 Associate Lecturer at Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta: 2014 – 2017 Assitant Lecturer at Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta: 2017 till date 04. Special Assignment/Community Responsibilities i. Representative of COLAMRUD to College Board meeting of COLERM ii. Welfare coordinator of Dept of Communication and General Studies CGNS iii. Course Adviser to COLVET 200Level students on GNS courses iv. Member of Building and Welfare committee at Jesus the Comforter Parish of Redeem Christian Church, Ikereku Laderin, Abeokuta 05. -

Aduloju of Ado: a Nineteenth Century Ekiti Warlord

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 18, Issue 4 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 58-66 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Aduloju of Ado: A Nineteenth Century Ekiti Warlord Emmanuel Oladipo Ojo (Ph.D) Department of History & International Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, NIGERIA Abstract: For Yorubaland, south-western Nigeria, the nineteenth century was a century of warfare and gun- powder akin, in magnitude and extent, to that of nineteenth century Europe. Across the length and breadth of Yorubaland, armies fought armies until 1886 when Sir Gilbert Carter, British Governor of the Lagos Protectorate, intervened to restore peace. Since men are generally the products of the times in which they live and the circumstances with which they are surrounded; men who live during the period of peace and tranquillity are most likely to learn how to promote and sustain peace while those who live in periods of turbulence and turmoil are most likely to learn and master the art of warfare. As wars raged and ravaged Yoruba nations and communities, prominent men emerged and built armies with which they defended their nations and aggrandised themselves. Men like Latosisa, Ajayi Ogboriefon and Ayorinde held out for Ibadan; Obe, Arimoro, Omole, Odo, Edidi, Fayise and Ogedengbe Agbogungboro for Ijesa; Karara for Ilorin; Ogundipe for Abeokuta; Ologun for Owo; Bakare for Afa; Ali for Iwo, Oderinde for Olupona, Onafowokan and Kuku for Ijebuode, Odu for Ogbagi; Adeyale for Ila; Olugbosun for Oye and Ogunbulu for Aisegba. Like other Yoruba nations and kingdoms, Ado Kingdom had its own prominent warlords. -

Bubonic Plague and Health Interventions in Colonial Lagos

Gesnerus 76/1 (2019) 90–110 Beyond “White Medicine”: Bubonic Plague and Health Interventions in Colonial Lagos Olukayode A. Faleye & Tanimola M. Akande Summary While studies have unveiled the implications of the bubonic plague outbreak in colonial Lagos in the areas of town planning, environmental health and trade, there is a dearth of scholarly writings on the multiplex nature of the biomedical, Christian, Muslim, non-Christian and non-Muslim African re- sponses to the epidemic outbreak. Based on the historical analysis of colonial medical records, newspaper reports, interviews and the literature, this paper concludes that the multiplex and transcultural nature of local responses to the bubonic plague in Lagos disavow the Western biomedical triumphalist claims to epidemic control in Africa during colonial rule. Keywords: African Responses, Biomedicine, Bubonic plague, Colonial Lagos, Christian Responses, Health Interventions, Muslim Responses Introduction The name “Lagos” is believed to have emanated from European origin – a bastardised form of “lago” (lake) as named by early Portuguese visitors to West Africa.1 According to oral tradition, Lagos, Nigeria was originally set- tled by migrant fi shermen, farmers, and warriors from Ile-Ife, Mahin and 1 Mann 2007, 26–27. Olukayode A. Faleye, Department of History and International Studies, Edo University Iyamho, Nigeria, Tel.: +2348034728908, [email protected], (Principal and Correspond- ing Author) Tanimola M. Akande, Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Nigeria, [email protected] 90 Gesnerus 76 (2019) Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 10:32:10PM via free access Benin.2 Lagos was annexed by the British in 1861. -

Nigerian Automotive Assembly Plants Capacities, Dealers

NIGERIAN AUTOMOTIVE ASSEMBLY PLANTS CAPACITIES, DEALERS PRODUCT/ S/N COMPANY NAME OFFICE ADDRESS FACTORY ADDRESS BRAND Plot W/L Ind.Layout Emene, P.O Pick ups, buses, SUVs, No2,Innoson Industrial Estate,Akwa-Uru,Nnewi,Anambar Innoson Vehicle refuse disposal trucks, 1 Box 1570,Enugu,Enugu State. Manufacturing Co. Ltd. ambulance etc/IVM Plot 18,Airport Road,Industrial Trucks and Emene Industrial Layout,P.M.B 2523,Enugu 2 ANAMMCO Layout,Emene,Enugu. buses/Mercedez, Yutong buses 78, Onilewura street, off Segun Truck and tanker bodies, 8,Lisabi Street,Apapa,Lagos,Lagos. Iron Products Industries 3 Iretin Street, Ikotun, Lagos. buses./ Tata Ltd. (IPI) (negotiation) plot 13/18 Raji Alabi Layout wofun Truck and buses/ FAW Km 8,Layland Industrial Estate. 4 Leyland Busan Motors Ltd. olodo Iwo Road Ibadan. plot 225,Moshood Abiola Way. Pick-ups, trucks, buses, Km 11, Zaria Road,Na,ibawa,Kano. SUVs, agricultural 5 National Trucks Manufacturers tractors etc./ Sino trucks Plot 1144,Mal,Kulbi Road,Kakuri Cars and Plot 1144,Mal,kilbi Road,kakuri Industria Estate P.M.B 2266,Kaduna. Industrial Estate P.M.B 2266,Kaduna. buses/Peuguot. 6 PAN Nig.Ltd 54,Balarabe Musa Crescent,off Armoured vans and Ode-Remo,Ogun State. 7 Proforce Ltd. Samuel Manuwa Road Victoria buses/ Proforce Island,Lagos 157,Apapa/Oshodi Trucks and buses/MAN 157,Apapa/oshodi,Expressway,Isolo,Oshodi. 8 Scoa Nigeria Plc. Expressway,Isolo,P.O.Box 2318,Lagos. 5 Alh.Akinwunmi St,Mushin,Lagos. Trucks,buses,motorcycle Industrial Estate,P.M.B 0135,Bauchi. 9 Steyr Nigeria Ltd s,tractors/steyr Plot 1, Block A, Gbagada Industrial Cars,SUVs,mini- Plot 1,Block A, Gbagada Industrial Estate,Lagos Stallion Nissan Motors Nigeria 10 Estate,Lagos buses,pick-ups/Nissan Ltd 270A, Ajose Adeogun Trucks,buses/Ashok 270A, Ajose Adeogun Street,Victoria Island,Lagos 11 Stallion Motors Ltd Street,Victoria Island,Lagos.