Ogun in Precolonial Yorubaland a Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Sanya Onabamiro – Copepods - Biology/Ecology – Guineaworm Transmission Copepods Identified & Characterised by Dr

Tropical Diseases in Africa Four Phases • Devastation • Discovery • Development • Deployment Pre-colonial & early colonial era Deaths of Europeans in West Africa Expedition Year Europeans Deaths Mungo Park 1805 44 39 Tuckey 1816 44 21 Clapperton 1825-7 5 4 MacGregor-Laird 1832-4 41 32 Trotter 1841 145 42 Take care and beware of the Bight of Benin For few come out, though many go in Arab African Mixed Meningitis in Africa Meningitis Belt Countries >15 cases per 100,000 population Seasonal Epidemics in Meningitis Belt Discovery •Trypanosomiasis •Yellow Fever •Malaria •Kwashiokhor Trypanosomiasis Milestones • 1902 Ford and Dutton, identified Trypanosoma brucei gambiense . • 1903 Castellani in Uganda parasite in CSF • 1903 David Bruce –tsetse fly as the vector • 1906 Ayres Kopke - arsenic drug, Atoxyl. • 1924 Tryparsamide less toxic than Atoxyl, • 1932 Atoxyl blinded 700 patients became Friedheim developed melarsoprol Numerous Tsetse Flies Yellow Fever Americas • Finlay – mosquito transmission • Walter Reed – viral agent, extrinsic incubation period in Aedes Aegypti Africa • Noguchi - Accra • Stokes - Lagos Live vaccine developed Tools for Disease Control Few remedies until mid-20th century • Salvarsan - syphilis • Antrypol -trypanosomiasis, onchocersiasis), • Pamaquine, chloroquine, primaquine, and pyrimethamine - malaria • Penicillin - yaws • Dapsone - leprosy Colonial Health Research • Expeditions • Colonial Medical Services • Research Institutes • Schools of Tropical Medicine in Europe • International Research Institutes European Scientists in Africa Outstanding world class scientists • Robert Koch • Aldo Castellani • George MacDonald Dr. Cecily Williams Jamaican, 1893-1992 1923 Graduated in Medicine, …Oxford University 1929-36 Served in Gold Coast Learnt Twi Identified Kwashiokhor 1936- Worked in 58 countries 1941-45 Prisoner of war “Health Education is listening to the people” Major C. -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming Javier Diaz The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2966 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MEANING BEYOND WORDS: A MUSICAL ANALYSIS OF AFRO-CUBAN BATÁ DRUMMING by JAVIER DIAZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2019 2018 JAVIER DIAZ All rights reserved ii Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor in Musical Arts. ——————————— —————————————————— Date Benjamin Lapidus Chair of Examining Committee ——————————— —————————————————— Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Peter Manuel, Advisor Janette Tilley, First Reader David Font-Navarrete, Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz Advisor: Peter Manuel This dissertation consists of a musical analysis of Afro-Cuban batá drumming. Current scholarship focuses on ethnographic research, descriptive analysis, transcriptions, and studies on the language encoding capabilities of batá. -

A Historical Survey of Socio-Political Administration in Akure Region up to the Contemporary Period

European Scientific Journal August edition vol. 8, No.18 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION IN AKURE REGION UP TO THE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD Afe, Adedayo Emmanuel, PhD Department of Historyand International Studies,AdekunleAjasin University,Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract Thepaper examines the political transformation of Akureregion from the earliest times to the present. The paper traces these stages of political development in order to demonstrate features associated with each stage. It argues further that pre-colonial Akure region, like other Yoruba regions, had a workable political system headed by a monarch. However, the Native Authority Ordinance of 1916, which brought about the establishment of the Native Courts and British judicial administration in the region led to the decline in the political power of the traditional institution.Even after independence, the traditional political institution has continually been subjugated. The work relies on both oral and written sources, which were critically examined. The paper, therefore,argues that even with its present political status in the contemporary Nigerian politics, the traditional political institution is still relevant to the development of thesociety. Keywords: Akure, Political, Social, Traditional and Authority Introduction The paper reviews the political administration ofAkure region from the earliest time to the present and examines the implication of the dynamics between the two periods may have for the future. Thus,assessment of the indigenous political administration, which was prevalent before the incursion of the colonial administration, the political administration during the colonial rule and the present political administration in the region are examined herein.However, Akure, in this context, comprises the present Akure North, Akure South, and Ifedore Local Government Areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. -

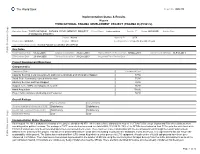

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Bascom Collection

William Russell Bascom Collection A survey of the documentation of the William Russell Bascom Collection at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley January 2019 Prepared by Lucy Portnoff, Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program with contributions by Delphine Sims, History of Art Graduate Student and update by Ira Jacknis and Linda Waterfield 1. Biographical Material, p.1 2. Publications, p.3 3. Summary of the Hearst Museum Accession Files and Permanent Collections, p.4 4. Summary of Material in the Hearst Museum Archive, p.7 5. Summary of Media Collection at the Hearst Museum, p.16 1. Biographical Material Relevant to Bascom William Russell Bascom was born on May 23, 1912 in Princeton, Illinois, and died on September 11, 1981 in San Francisco, California. Bascom received his B.A.in 1933 from the University of Wisconsin (Physics), his M.A. in 1936 from the University of Wisconsin (Anthropology), and his Ph.D. in 1939 from Northwestern University (Anthropology). Bascom specialized in the art and culture of West Africa and the African Diaspora, and is especially known for his studies of Nigerian Yoruba culture and religion. In 1954, Bascom crafted the “four functions of folklore.” He was the Director of the Robert H. Lowie Museum (present-day Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology) at the University of California, Berkeley from 1957 to 1979. Further biographical information can be found on the Online Archive of California Finding Aid to the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley:http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5p3035gz/ Index of Biographical Material at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley: William R. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

Introduction Urban Reproductive Health

Family Planning Effort Index Ibadan, Ilorin, Abuja, and Kaduna FPE Nigeria 2011 Introduction Nigeria has a current population of 152 million with a growth rate of 3.2%, a Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) of 15.4 and a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 5.7. Nigeria plays an important role in the socio- political context of West Africa, since it constitutes 50.2% of the total population of the region (PRB 2009, DHS 2008). In response to the pattern of high growth rates, the National Policy on Population for Sustainable Development was launched in 2005. The policy recognized that population factors, social and economic development, and environmental issues are irrevocably interconnected and addressing them are critical to the achievement of sustainable development in Nigeria. The Nigerian population policy sets specific targets aimed at addressing high rates of population growth including a reduction in the annual national growth rate to 2% or lower by 2015, a reduction in the TFR of at least 0.6 children per woman every five years, and an increase in CPR of at least 2% points per year. However, Nigeria still has a 20% unmet need for family planning (NPC and ICF Macro, 2009). Family Planning was included in the fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) as an indicator for tracking progress of improving maternal health. This concept of integrating family planning with maternal health services is the same approach that the Nigerian Ministry of Health is utilizing with messages related to family planning highlighting the links between utilization and reduced maternal mortality. However, continuing low levels of CPR and high levels of maternal mortality highlight the importance of an increased emphasis on family planning both within the context of maternal health and other health and social benefits. -

From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940

The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History ISSN: 0308-6534 (Print) 1743-9329 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fich20 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly To cite this article: Samuel Fury Childs Daly (2019) From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 47:3, 474-489, DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 Published online: 15 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 268 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fich20 THE JOURNAL OF IMPERIAL AND COMMONWEALTH HISTORY 2019, VOL. 47, NO. 3, 474–489 https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Indirect rule figured prominently in Nigeria’s colonial Nigeria; Abeokuta; crime; administration, but historians understand more about the police; indirect rule abstract tenets of this administrative strategy than they do about its everyday implementation. This article investigates the early history of the Native Authority Police Force in the town of Abeokuta in order to trace a larger move towards coercive forms of administration in the early twentieth century. In this period the police in Abeokuta developed from a primarily civil force tasked with managing crime in the rapidly growing town, into a political implement of the colonial government. -

Factors Affecting Effective Teaching and Learning of Economics in Some Ogbomosho High Schools, Oyo State, Nigeria

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.7, No.28, 2016 Factors Affecting Effective Teaching and Learning of Economics in Some Ogbomosho High Schools, Oyo State, Nigeria Gbemisola Motunrayo Ojo Vusy Nkoyane Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, College of Education, University of South Africa 0001 Abstract This study was carried out to examine the present curriculum of Economics as a subject in some Ogbomoso Senior High Schools and to determine factors affecting effective teaching of economics in the schools. Variables such as number of students, teachers’ ratio available textbooks were also examined. The study adopted descriptive design since it is an ex post facto research. The target population for this study is Ogbomosho North Local Government Area of Oyo State comprising nine (9) High Secondary Schools. Three (3) teachers of economics and five (5) students from each school were used in answering the questionnaires. The study revealed high number of economics students (5,864) as against 26 teachers in nine (9) public schools under study. This gives a very high teacher-student ratio of 1:225. The findings also showed that there one lack of teaching aids, library facilities and where available, there is lack of textbooks of Economics. All the schools studied were highly dense resulted into high students’ population. Based on the findings of his study, the federal and the state governments should employ more teachers, especially in Economics to checkmate rising teacher student ratio. More senior secondary schools should be built with the increasing student population within the LGA under study. -

“YORUBA's DON't DO GENDER”: a CRITICAL REVIEW of OYERONKE OYEWUMI's the Invention of Women

“YORUBA’S DON’T DO GENDER”: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF OYERONKE OYEWUMI’s The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses By Bibi Bakare-Yusuf Discourses on Africa, especially those refracted through the prism of developmentalism, promote gender analysis as indispensable to the economic and political development of the African future. Conferences, books, policies, capital, energy and careers have been made in its name. Despite this, there has been very little interrogation of the concept in terms of its relevance and applicability to the African situation. Instead, gender functions as a given: it is taken to be a cross-cultural organising principle. Recently, some African scholars have begun to question the explanatory power of gender in African societies.1 This challenge came out of the desire to produce concepts grounded in African thought and everyday lived realities. These scholars hope that by focusing on an African episteme they will avoid any dependency on European theoretical paradigms and therefore eschew what Babalola Olabiyi Yai (1999) has called “dubious universals” and “intransitive discourses”. Some of the key questions that have been raised include: can gender, or indeed patriarchy, be applied to non- Euro-American cultures? Can we assume that social relations in all societies are organised around biological sex difference? Is the male body in African societies seen as normative and therefore a conduit for the exercise of power? Is the female body inherently subordinate to the male body? What are