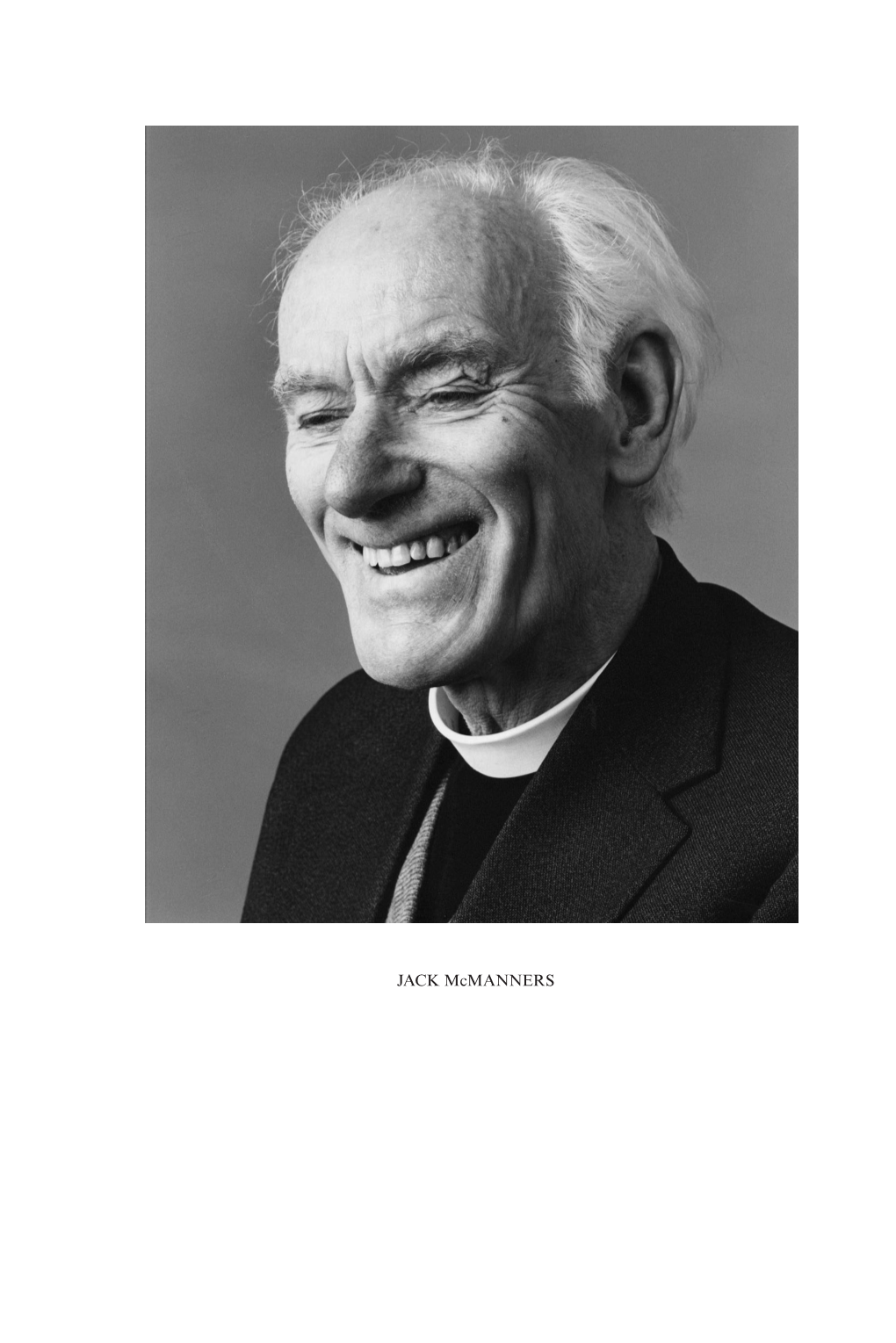

JACK Mcmanners John Mcmanners 1916–2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Full Book

Respectable Folly Garrett, Clarke Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Garrett, Clarke. Respectable Folly: Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.67841. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/67841 [ Access provided at 2 Oct 2021 03:07 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Clarke Garrett Respectable Folly Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3177-2 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3177-7 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3175-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3175-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3176-5 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3176-9 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. Respectable Folly RESPECTABLE FOLLY M illenarians and the French Revolution in France and England 4- Clarke Garrett The Johns Hopkins University Press BALTIMORE & LONDON This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Andrew W. -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700 Folger Shakespeare Library Spring Semester Seminar 2016 Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge): [email protected] The origins, impact and repercussions of the English Reformation have been the subject of lively debate. Although it is now widely recognised as a protracted process that extended over many decades and generations, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the links between the life cycle and religious change. Did age and ancestry matter during the English Reformation? To what extent did bonds of blood and kinship catalyse and complicate its path? And how did remembrance of these events evolve with the passage of the time and the succession of the generations? This seminar will investigate the connections between the histories of the family, the perception of the past, and England’s plural and fractious Reformations. It invites participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to explore how the religious revolutions and movements of the period shaped, and were shaped by, the horizontal relationships that early modern people formed with their sibilings, relatives and peers, as well as the vertical ones that tied them to their dead ancestors and future heirs. It will also consider the role of the Reformation in reconfiguring conceptions of memory, history and time itself. Schedule: The seminar will convene on Fridays 1-4.30pm, for 10 weeks from 5 February to 29 April 2016, excluding 18 March, 1 April and 15 April. In keeping with Folger tradition, there will be a tea break from 3.00 to 3.30pm. -

Layout 1 22/7/11 10:04 Page E

CCM 27 [9] [P]:Layout 1 22/7/11 10:04 Page e Chri Church Matters TRINITY TERM 2011 ISSUE 27 CCM 27 [9] [P]:Layout 1 22/7/11 10:02 Page b Editorial Contents ‘There are two educations; one should teach us how DEAN’S DIARY 1 to make a living and the other how to live’John Adams. CARDINAL SINS – Notes from the Archives 2 A BROAD EDUCATION – John Drury 4 “Education, education, education.” Few deny how important it is, but THE ART ROOM 5 how often do we actually stop to think what it is? In this 27th issue of Christ Church Matters two Deans define a balanced education, and REVISITING SAAKSHAR 6 members current and old illuminate the debate with stories of how they CATHEDRAL NEWS 7 fill or filled their time at the House. Pleasingly it seems that despite the increased pressures on students to gain top degrees there is still time to CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAL CHOIR – North American Tour 8 live life and attempt to fulfil all their talents. PICTURE GALLERY PATRONS’ LECTURE 10 The Dean mentions J. H. Newman. His view was that through a University THE WYCLIFFITE BIBLE – education “a habit of mind is formed which lasts through life, of which the Mishtooni Bose 11 attributes are freedom, equitableness, calmness, moderation, and wisdom. ." BOAT CLUB REPORT 12 Diversity was important to him too: "If [a student's] reading is confined simply ASSOCIATION NEWS AND EVENTS 13-26 to one subject, however such division of labour may favour the advancement of a particular pursuit . -

HIST 80000: Literature of Modern Europe I (Draft) CUNY Graduate

HIST 80000: Literature of Modern Europe I (Draft) CUNY Graduate Center, Wednesday, 4:15-6:15 p.m., 5 credits Professor David G. Troyansky Office 5104. Hours: 3:00-4:00 p.m., Wednesday, and by appointment. Direct line: 212 817-8453. Most of the week at Brooklyn College: 718 951-5303. E-mail: [email protected] This course is designed to introduce first-year students to some of the major debates and recent (and sometimes classic) books in European history from the 1750s to the 1870s. It is also intended to help prepare students for the First (Written) Examination. Objectives: By the end of the course, students should be able to demonstrate familiarity with many of the central historiographical issues in the period and to assess historical writings in terms of approach, use of sources, and argument. They should be able to draw on multiple works to make larger arguments concerning major problems in European history. Requirements: Each week, students will come to class prepared to discuss assigned readings. They include common readings and individual works chosen from the supplementary lists. In anticipation of the next day’s class, by early Tuesday evening, students will have submitted by email to the instructor and to the rest of the class a two-to-three-page (double-spaced) paper on their week’s readings. Eleven papers must be submitted; two weeks may be skipped, but even then everyone is expected to be prepared for discussion. The papers should not simply summarize. They should explain and compare the theses of the assigned books; describe the authors’ methods, arguments, and sources; and assess their persuasiveness, significance, and implications. -

The Classicism of Hugh Trevor-Roper

1 THE CLASSICISM OF HUGH TREVOR-ROPER S. J. V. Malloch* University of Nottingham, U.K. Abstract Hugh Trevor-Roper was educated as a classicist until he transferred to history, in which he made his reputation, after two years at Oxford. His schooling engendered in him a classicism which was characterised by a love of classical literature and style, but rested on a repudiation of the philological tradition in classical studies. This reaction helps to explain his change of intellectual career; his classicism, however, endured: it influenced his mature conception of the practice of historical studies, and can be traced throughout his life. This essay explores a neglected aspect of Trevor- Roper’s intellectual biography through his ‘Apologia transfugae’ (1973), which explains his rationale for abandoning classics, and published and unpublished writings attesting to his classicism, especially his first publication ‘Homer unmasked!’ (1936) and his wartime notebooks. I When the young Hugh Trevor-Roper expressed a preference for specialising in mathematics in the sixth form at Charterhouse, Frank Fletcher, the headmaster, told him curtly that ‘clever boys read classics’.1 The passion that he had already developed for Homer in the under sixth form spread to other Greek and Roman authors. In his final year at school he won two classical prizes and a scholarship that took him in 1932 to Christ Church, Oxford, to read classics, literae humaniores, then the most * Department of Classics, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD. It was only by chance that I developed an interest in Hugh Trevor-Roper: in 2010 I happened upon his Letters from Oxford in a London bookstore and, reading them on the train home, was captivated by the world they evoked and the style of their composition. -

Essay Reviews

Essay Reviews DEATH AND THE DOCTORS PHILIPPE ARIES, The hour ofour death, London, Allen Lane, 1981, 8vo, pp. xxii, 652, illus., £14.95. ROBERT CHAPMAN, IAN KINNES, and KLAUS RANDSBORG (editors), The archaeology ofdeath, Cambridge University Press, 1981, 4to, pp. 158, illus., £17.50. JOHN McMANNERS, Death and the Enlightenment. Changing attitudes to death among Christians and unbelievers in eighteenth-century France,'Oxford University Press, 1981, 8vo, pp. vii, 619, £17.50. JOACHIM WHALEY (editor), Mirrors ofmortality. Studies in the social history of death, London, Europa, 1981, pp. vii, 252, £19.50. There is no more universal social fact than death ("never send to know for whom the bell tolls"). Yet death is the topic supremely difficult for historians to research, since, though all live under its shadow, none has experienced it directly for himself, and there are no scientific tests of its most momentous putative consequence, an afterlife, for which men have slain and been slain. It is, nevertheless, a fashionable subject of inquiry, gaining 6clat first in France, and now, like so many other Paris fas- hions, being exported to Britain and across the Atlantic. One can chronicle death at the most metaphysical level (as in Norman 0. Brown's Life against Death (1959), a Freudian psychohistory of mankind, viewing civilization as a holding operation, keeping death at bay, a bid on immortality), or in the most personal terms, as in Victor and Rosemary Zorza's Kindertotenbuch, A way ofdying (1980), which offers a moving account of the agonies of coming to terms with the departure of a loved one. -

HISTORY of CHRISTIANITY II February-April 2019: Reformed Theological Seminary, Atlanta ______Professor: Ken Stewart, Ph.D

1 HISTORY OF CHRISTIANITY II February-April 2019: Reformed Theological Seminary, Atlanta ___________________________________________________ Professor: Ken Stewart, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Phone: 706.419.1653 (w); 423.414.3752 (cell) Course number: 04HT504 Class Dates: Friday evening 7:00-9:00 pm and Saturday 8:30-5:30 p.m. February 1&2, March 1&2, March 29&30, April 26&27 Catalog Course Description: A continuation of HT502, concentrating on great leaders of the church in the modern period of church history from the Reformation to the nineteenth century. Course Objectives: To grasp the flow of Christian history in the western world since 1500 A.D., its interchange with the non-western world in light of transoceanic exploration and the challenges faced through the division of Christendom at the Reformation, the rise of Enlightenment ideas, the advance of secularization and the eventual challenge offered to the dominance of Europe. To gain the ability to speak and write insightfully regarding the interpretation of this history and the application of its lessons to modern Christianity Course Texts (3): Henry Bettenson & Chris Maunder, eds. Documents of the Christian Church 4th Edition, (Oxford, 2011) Be sure to obtain the 4th edition as documents will be identified by page no. Justo Gonzáles, The Story of Christianity Vol. II, 2nd edition (HarperOne, 2010) insist on 2nd ed. Kenneth J. Stewart, Ten Myths about Calvinism (InterVarsity, 2011) [Economical used editions of all titles are available from the following: amazon.com; abebooks.com; betterworldbooks.com; thriftbooks.com] The instructor also recommends (but does not require), Tim Dowley, ed. -

Chris Church Matters TRINITY Term 2013 Issue 31 Editorial Contents

Chris Church Matters TRINITY TERM 2013 ISSUE 31 Editorial Contents Only a life lived in the service to others is worth living. DEAn’S DIARy 1 albert einstein CATHEDRAl nEWS: The Office for the Royal Maundy 2 The idea of service permeates much that appears in this edition of Christ CARDInAl SInS – Notes from the archives 4 Church Matters. Christopher Lewis celebrates his tenth year as Dean this year, and he writes about our Visitor in his Diary. There can surely CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAl CHoIR 6 be nobody in the country who better personifies the ideals of duty and CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAl SCHool 7 service than Queen Elizabeth II: “I have in sincerity pledged myself to your service, as so many of you are pledged to mine. Throughout all my life CHRIST CHURCH CollEGE CHoIR 8 and with all my heart I shall strive to be worthy of your trust.” THE nEWS fRoM EvEREST, 1953 10 Many of our thirteen Prime Ministers whom the Archivist writes about also stressed the ideal. W. E. Gladstone, whom another member JoSEPH BAnkS 12 of the House, Lord (Nigel) Lawson, called “the greatest Chancellor of all EnGRAvED GEMS AnD THE UPPER lIBRARy 14 time”, stated that “selfishness is the greatest curse of the human race” A PRICElESS CollECTIon of THEATRICAl EPHEMERA 16 (and Churchill is alleged to have said “They told me how Mr. Gladstone read Homer for fun, which I thought served him right.”) ASSoCIATIon nEWS & EvEnTS 17-27 Service, to the House, is also epitomised by the authors of the next PoETRy 28 two articles, Stephen Darlington and the Cathedral School headmaster, Martin Bruce, as it is by the choristers in the both the Cathedral and the ovAlHoUSE AT 50 30 College choirs. -

Cunning Folk and Wizards in Early Modern England

Cunning Folk and Wizards In Early Modern England University ID Number: 0614383 Submitted in part fulfilment for the degree of MA in Religious and Social History, 1500-1700 at the University of Warwick September 2010 This dissertation may be photocopied Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 1 Who Were White Witches and Wizards? 8 Origins 10 OccupationandSocialStatus 15 Gender 20 2 The Techniques and Tools of Cunning Folk 24 General Tools 25 Theft/Stolen goods 26 Love Magic 29 Healing 32 Potions and Protection from Black Witchcraft 40 3 Higher Magic 46 4 The Persecution White Witches Faced 67 Law 69 Contemporary Comment 74 Conclusion 87 Appendices 1. ‘Against VVilliam Li-Lie (alias) Lillie’ 91 2. ‘Popular Errours or the Errours of the people in matter of Physick’ 92 Bibliography 93 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my undergraduate and postgraduate tutors at Warwick, whose teaching and guidance over the years has helped shape this dissertation. In particular, a great deal of gratitude goes to Bernard Capp, whose supervision and assistance has been invaluable. Also, to JH, GH, CS and EC your help and support has been beyond measure, thank you. ii Cunning folk and Wizards in Early Modern England Witchcraft has been a reoccurring preoccupation for societies throughout history, and as a result has inspired significant academic interest. The witchcraft persecutions of the early modern period in particular have received a considerable amount of historical investigation. However, the vast majority of this scholarship has been focused primarily on the accusations against black witches and the punishments they suffered. -

Geoffrey Best

GEOFFREY BEST Geoffrey Francis Andrew Best 20 November 1928 – 14 January 2018 elected Fellow of the British Academy 2003 by BOYD HILTON Fellow of the Academy Restless and energetic, Geoffrey Best moved from one subject area to another, estab- lishing himself as a leading historian in each before moving decisively to the next. He began with the history of the Anglican Church from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, then moved by turns to the economy and society of Victorian Britain, the history of peace movements and the laws of war, European military history and the life of Winston Churchill. He was similarly peripatetic in terms of institutional affili- ation, as he moved from Cambridge to Edinburgh, then Sussex, and finally Oxford. Although his work was widely and highly praised, he remained self-critical and could never quite believe in his own success. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, XIX, 59–84 Posted 28 April 2020. © British Academy 2020. GEOFFREY BEST Few historians write their autobiography, but since Geoffrey Best did A Life of Learning must be the starting-point for any appraisal of his personal life.1 It is a highly readable text—engaging, warm-hearted and chatty like the man himself—but inevit- ably it invites interrogation. For example, there is the problem of knowing when the author is describing how he felt on past occasions and when he is ruminating about those feelings in retrospect. In the latter mode he writes that he has ‘never ceased to be surprised by repeatedly discovering how ignorant, wrong and naïve I have been about people and institutions, and still am’ (p. -

Greater Britain: a Useful Category of Historical Analysis?

!"#$%#"&'"(%$()*&+&,-#./0&1$%#23"4&3.&5(-%3"(6$0&+)$04-(-7 +/%83"9-:*&;$<(=&+">(%$2# ?3/"6#*&@8#&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&A#<(#BC&D30E&FGHC&I3E&JC&9+K"EC&FLLL:C&KKE&HJMNHHO P/Q0(-8#=&Q4*&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&+--36($%(3) ?%$Q0#&,AR*&http://www.jstor.org/stable/2650373 +66#--#=*&SGTGUTJGGV&FV*SU Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org AHR Forum Greater Britain: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis? DAVID ARMITAGE THE FIRST "BRITISH" EMPIRE imposed England's rule over a diverse collection of territories, some geographically contiguous, others joined to the metropolis by navigable seas.