The Classicism of Hugh Trevor-Roper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

GREEK and LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’S Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ

Blackwell’s Rare Books Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Blackwell’S rare books Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’s Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/ rarebooks Our premises are in the main Blackwell bookstore at 48-51 Broad Street, one of the largest and best known in the world, housing over 200,000 new book titles, covering every subject, discipline and interest, as well as a large secondhand books department. There is lift access to each floor. The bookstore is in the centre of the city, opposite the Bodleian Library and Sheldonian Theatre, and close to several of the colleges and other university buildings, with on street parking close by. Oxford is at the centre of an excellent road and rail network, close to the London - Birmingham (M40) motorway and is served by a frequent train service from London (Paddington). Hours: Monday–Saturday 9am to 6pm. (Tuesday 9:30am to 6pm.) Purchases: We are always keen to purchase books, whether single works or in quantity, and will be pleased to make arrangements to view them. Auction commissions: We attend a number of auction sales and will be happy to execute commissions on your behalf. Blackwell online bookshop www.blackwell.co.uk Our extensive online catalogue of new books caters for every speciality, with the latest releases and editor’s recommendations. -

Download Full Book

Respectable Folly Garrett, Clarke Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Garrett, Clarke. Respectable Folly: Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.67841. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/67841 [ Access provided at 2 Oct 2021 03:07 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Clarke Garrett Respectable Folly Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3177-2 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3177-7 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3175-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3175-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3176-5 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3176-9 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. Respectable Folly RESPECTABLE FOLLY M illenarians and the French Revolution in France and England 4- Clarke Garrett The Johns Hopkins University Press BALTIMORE & LONDON This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Andrew W. -

Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire by David Graeber

POSSIBILITIES Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire POSSIBILITIES Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire David Graeber Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire by David Graeber ISBN 978-1904859-66-6 Library of Congress Number: 2007928387 ©2007 David Graeber This edition © 2007 AK Press Cover Design: John Yates Layout: C. Weigl & Z. Blue Proofreader: David Brazil AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612 www.akpress.org akpress @akpress.org 510.208.1700 AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh EH8 9YE www.akuk.com [email protected] 0131.555.5165 Printed in Canada on 100% recycled, acid-free paper by union labor. TABLE OF CONTENTS In tro d u c tio n ....................................................................................................................... 1 PART I: SOME THOUGHTS ON THE ORIGINS OF OUR CURRENT PREDICAMENT 1 Manners, Deference, and Private Property: Or, Elements for a General Theory of Hierarchy................................................................................................... 13 2 The Very Idea of Consumption: Desire, Phantasms, and the Aesthetics of Destruction from Medieval Times to the Present...............................................57 3 Turning Modes of Production Inside-Out: Or, Why Capitalism Is a Transformation of Slavery (short version).......................................................... 85 4 Fetishism as Social Creativity: Or, Fetishes Are Gods in the Process of C onstruction.................................................................................................................113 -

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700 Folger Shakespeare Library Spring Semester Seminar 2016 Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge): [email protected] The origins, impact and repercussions of the English Reformation have been the subject of lively debate. Although it is now widely recognised as a protracted process that extended over many decades and generations, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the links between the life cycle and religious change. Did age and ancestry matter during the English Reformation? To what extent did bonds of blood and kinship catalyse and complicate its path? And how did remembrance of these events evolve with the passage of the time and the succession of the generations? This seminar will investigate the connections between the histories of the family, the perception of the past, and England’s plural and fractious Reformations. It invites participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to explore how the religious revolutions and movements of the period shaped, and were shaped by, the horizontal relationships that early modern people formed with their sibilings, relatives and peers, as well as the vertical ones that tied them to their dead ancestors and future heirs. It will also consider the role of the Reformation in reconfiguring conceptions of memory, history and time itself. Schedule: The seminar will convene on Fridays 1-4.30pm, for 10 weeks from 5 February to 29 April 2016, excluding 18 March, 1 April and 15 April. In keeping with Folger tradition, there will be a tea break from 3.00 to 3.30pm. -

DEMOPOLIS Democracy Before Liberalism in Theory and Practice

Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 DEMOPOLIS Democracy before Liberalism in Theory and Practice JOSIAH OBER Stanford University, California v Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 Contents List of Figures page xi List of Tables xii Preface: Democracy before Liberalism xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on the Text xix 1 Basic Democracy 1 1.1 Political Theory 1 1.2 Why before Liberalism? 5 1.3 Normative Theory, Positive Theory, History 11 1.4 Sketch of the Argument 14 2 The Meaning of Democracy in Classical Athens 18 2.1 Athenian Political History 19 2.2 Original Greek Defnition 22 2.3 Mature Greek Defnition 29 3 Founding Demopolis 34 3.1 Founders and the Ends of the State 36 3.2 Authority and Citizenship 44 3.3 Participation 48 3.4 Legislation 50 3.5 Entrenchment 52 3.6 Exit, Entrance, Assent 54 3.7 Naming the Regime 57 4 Legitimacy and Civic Education 59 4.1 Material Goods and Democratic Goods 60 4.2 Limited-Access States 63 4.3 Hobbes’s Challenge 64 4.4 Civic Education 71 ix Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 x Contents 5 Human Capacities and Civic Participation 77 5.1 Sociability 79 5.2 Rationality 83 5.3 Communication 87 5.4 Exercise of Capacities as a Democratic Good 88 5.5 Free Exercise and Participatory Citizenship 93 5.6 From Capacities to Security and Prosperity 98 6 Civic Dignity -

Cunning Folk and Wizards in Early Modern England

Cunning Folk and Wizards In Early Modern England University ID Number: 0614383 Submitted in part fulfilment for the degree of MA in Religious and Social History, 1500-1700 at the University of Warwick September 2010 This dissertation may be photocopied Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 1 Who Were White Witches and Wizards? 8 Origins 10 OccupationandSocialStatus 15 Gender 20 2 The Techniques and Tools of Cunning Folk 24 General Tools 25 Theft/Stolen goods 26 Love Magic 29 Healing 32 Potions and Protection from Black Witchcraft 40 3 Higher Magic 46 4 The Persecution White Witches Faced 67 Law 69 Contemporary Comment 74 Conclusion 87 Appendices 1. ‘Against VVilliam Li-Lie (alias) Lillie’ 91 2. ‘Popular Errours or the Errours of the people in matter of Physick’ 92 Bibliography 93 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my undergraduate and postgraduate tutors at Warwick, whose teaching and guidance over the years has helped shape this dissertation. In particular, a great deal of gratitude goes to Bernard Capp, whose supervision and assistance has been invaluable. Also, to JH, GH, CS and EC your help and support has been beyond measure, thank you. ii Cunning folk and Wizards in Early Modern England Witchcraft has been a reoccurring preoccupation for societies throughout history, and as a result has inspired significant academic interest. The witchcraft persecutions of the early modern period in particular have received a considerable amount of historical investigation. However, the vast majority of this scholarship has been focused primarily on the accusations against black witches and the punishments they suffered. -

Geoffrey Best

GEOFFREY BEST Geoffrey Francis Andrew Best 20 November 1928 – 14 January 2018 elected Fellow of the British Academy 2003 by BOYD HILTON Fellow of the Academy Restless and energetic, Geoffrey Best moved from one subject area to another, estab- lishing himself as a leading historian in each before moving decisively to the next. He began with the history of the Anglican Church from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, then moved by turns to the economy and society of Victorian Britain, the history of peace movements and the laws of war, European military history and the life of Winston Churchill. He was similarly peripatetic in terms of institutional affili- ation, as he moved from Cambridge to Edinburgh, then Sussex, and finally Oxford. Although his work was widely and highly praised, he remained self-critical and could never quite believe in his own success. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, XIX, 59–84 Posted 28 April 2020. © British Academy 2020. GEOFFREY BEST Few historians write their autobiography, but since Geoffrey Best did A Life of Learning must be the starting-point for any appraisal of his personal life.1 It is a highly readable text—engaging, warm-hearted and chatty like the man himself—but inevit- ably it invites interrogation. For example, there is the problem of knowing when the author is describing how he felt on past occasions and when he is ruminating about those feelings in retrospect. In the latter mode he writes that he has ‘never ceased to be surprised by repeatedly discovering how ignorant, wrong and naïve I have been about people and institutions, and still am’ (p. -

Greater Britain: a Useful Category of Historical Analysis?

!"#$%#"&'"(%$()*&+&,-#./0&1$%#23"4&3.&5(-%3"(6$0&+)$04-(-7 +/%83"9-:*&;$<(=&+">(%$2# ?3/"6#*&@8#&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&A#<(#BC&D30E&FGHC&I3E&JC&9+K"EC&FLLL:C&KKE&HJMNHHO P/Q0(-8#=&Q4*&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&+--36($%(3) ?%$Q0#&,AR*&http://www.jstor.org/stable/2650373 +66#--#=*&SGTGUTJGGV&FV*SU Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org AHR Forum Greater Britain: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis? DAVID ARMITAGE THE FIRST "BRITISH" EMPIRE imposed England's rule over a diverse collection of territories, some geographically contiguous, others joined to the metropolis by navigable seas. -

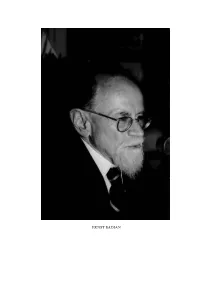

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

EDWARD COURTNEY 1932-2019 Edward

EDWARD COURTNEY 1932-2019 Edward Courtney was born on 22 March 1932 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, to George, an administrator in the court system, and Kathleen. He had a sister and many cousins, of whom three became university lecturers. In 1943, at the age of eleven, he entered the Royal Belfast Academical Institution, which was also to produce J.C. McKeown, J.L. Moles and R.K. Gibson. When Gibson was a research student in Cambridge and met Ted (as he was universally known) for the first time, he asked him how he had retained his Belfast accent; ‘I never listen to anybody else!’ was the perhaps surprising (and certainly misleading) reply. At ‘Inst.’ Ted was taught by H.C. Fay, later to produce a school edition of Plautus’ Rudens (1969), and John Cowser, who, by lending him Housman’s editions of Juvenal and Lucan, instilled in him a preference for Latin over Greek. Three decades later, in 1980, Ted would publish the standard commentary on Juvenal, followed after four years by a critical edition of the text; and, after moving to Charlottesville in the 1990s, he would drive around town in a car whose licence-plate was ‘JUVENAL’, bought for him as a birthday present by his wife. At Inst. Ted was introduced to the verse composition in Greek and Latin which was to stand him in such good stead in later years, and he was taught to play chess by a friend: in 1950 he won the Irish Junior Championship and the Irish Premier Reserves tournament, and captained the Irish schoolboy team against England and Wales. -

The Robe of Iphigenia in Agamemnon Anne Lebeck

The Robe of Iphigenia in "Agamemnon" Lebeck, Anne Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Spring 1964; 5, 1; ProQuest pg. 35 The Robe of Iphigenia in Agamemnon Anne Lebeck HE CHORAL LYRIC (104-263) immediately following the anapestic Tparodos of Agamemnonl closes with a description of the sacrifice at Aulis in which the robes of Iphigenia playa prominent part (7T€:TTAotaL 7TEpL7TETTJ [233J; KPOKOU f3acptx~ 0' €~ 7T€OOJl x€ouaa [239J). There are two interpretations of the lines in question. Most scholars regard the verbal adjective 7T€PL7TET~~ in line 233 as passive, the dative 7T€7TAOLGL as instrumental, and translate "wrapped round in her robes" (Fraenkel, Headlam, Mazon, Smyth, Verrall). Line 239 is taken to mean that Iphigenia disrobes completely,2 "her saffron garment fall ing on the ground." Professor Lloyd-Jones3 recently offered a more convincing interpretation than the earlier view that Iphigenia sheds her peplos. Line 239, which means literally "pouring dye of saffron toward the ground," describes Iphigenia raised above the altar; from her body, held horizontally,4 the robe trails down. In the same article Lloyd-Jones ingeniously suggests that 7TEPL7TET~~ is active, the robes those of Agamemnon. Iphigenia kneels before her father in supplication, "with her arms flung about his robes."5 Pro fessor Page remarks, "This interpretation has great advantages: the thought and the language are now both of a normal type .... "6 Such an advantage is questionable, since neither the thought nor the lang uage of this passage are normal. Rather they are lyrical: disconnected phrases follow one another in rapid succession, evoking a strange and dreamlike picture.