Ludlow Griscom; the Birdwatcher's Guru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Watcher's General Store

BIRD OBSERVER BIRD OBSERVER ^4^ ■ ^ '- V - iIRDOBSEl jjjijdOBSEKSK fi« o , bs«s^2; bird observer ®^«D 0BS£, VOL. 21 NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 BIRD OBSERVER • s bimonthly {ournal • To enhance understanding, observation, and enjoyment of birds. VOL. 21, NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 Editor In Chief Corporate Officers Board of Directors Martha Steele President Dorothy R. Arvidson Associate Editor William E. Davis, Jr. Alden G. Clayton Janet L. Heywood Treasurer Herman H. D'Entremont Lee E. Taylor Department Heads H. Christian Floyd Clerk Cover Art Richard A. Forster Glenn d'Entremont William E. Davis, Jr. Janet L. Heywood Where to Go Birding Subscription Manager Harriet E. Hoffman Jim Berry David E. Lange John C. Kricher Feature Articles and Advertisements David E. Lange Field Notes Robert H. Stymeist John C. Kricher Simon Perkins Book Reviews Associate Staff Wayne R. Petersen Alden G. Clayton Theodore Atkinson Marjorie W. Rines Bird Sightings Martha Vaughan John A. Shetterly Robert H. Stymeist Editor Emeritus Martha Steele At a Glance Dorothy R. Arvidson Robert H. Stymeist Wayne R. Petersen BIRD OBSERVER {USPS 369-850) is published bimonthly, COPYRIGHT © 1993 by Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts, Inc., 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178, a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation under section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Gifts to Bird Observer will be greatly appreciated and are tax deductible. POSTMASTER; Send address changes to BIRD OBSERVER, 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $16 for 6 issues, $30 for two years in the U. S. Add $2.50 per year for Canada and foreign. Single copies ^ .0 0 . -

Early Birding Book

Early Birding in Dutchess County 1870 - 1950 Before Binoculars to Field Guides by Stan DeOrsey Published on behalf of The Ralph T. Waterman Bird Club, Inc. Poughkeepsie, New York 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Stan DeOrsey All rights reserved First printing July 2016 Digital version June 2018, with minor changes and new pages added at the end. Digital version July 2019, pages added at end. Cover images: Front: - Frank Chapman’s Birds of Eastern North America (1912 ed.) - LS Horton’s post card of his Long-eared Owl photograph (1906). - Rhinebeck Bird Club’s second Year Book with Crosby’s “Birds and Seasons” articles (1916). - Chester Reed’s Bird Guide, Land Birds East of the Rockies (1908 ed.) - 3x binoculars c.1910. Back: 1880 - first bird list for Dutchess County by Winfrid Stearns. 1891 - The Oölogist’s Journal published in Poughkeepsie by Fred Stack. 1900 - specimen tag for Canada Warbler from CC Young collection at Vassar College. 1915 - membership application for Rhinebeck Bird Club. 1921 - Maunsell Crosby’s county bird list from Rhinebeck Bird Club’s last Year Book. 1939 - specimen tag from Vassar Brothers Institute Museum. 1943 - May Census checklist, reading: Raymond Guernsey, Frank L. Gardner, Jr., Ruth Turner & AF [Allen Frost] (James Gardner); May 16, 1943, 3:30am - 9:30pm; Overcast & Cold all day; Thompson Pond, Cruger Island, Mt. Rutson, Vandenburg’s Cove, Poughkeepsie, Lake Walton, Noxon [in LaGrange], Sylvan Lake, Crouse’s Store [in Union Vale], Chestnut Ridge, Brickyard Swamp, Manchester, & Home via Red Oaks Mill. They counted 117 species, James Gardner, Frank’s brother, added 3 more. -

Bird Watchers and the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology a Thesis S

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE LISTENING AT THE LAB: BIRD WATCHERS AND THE CORNELL LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE By JACKSON RINN POPE III Norman, Oklahoma 2016 LISTENING AT THE LAB: BIRD WATCHERS AND THE CORNELL LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF SCIENCE BY ______________________________ Dr. Katherine Pandora, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Piers Hale ______________________________ Dr. Stephen Weldon ______________________________ Dr. Zev Trachtenberg © Copyright by JACKSON RINN POPE III 2016 All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction, 1 Brief History of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 3 Chapter Overview, 7 Historiography, 10 Bird Watching and Ornithology, 10 Observational Science and Amateur Participation, 23 Natural History and New Media, 31 Chapter One: Collection, Conservation, and Community, 35 Introduction, 35 The Culture of Collecting, 36 Cultural Conflict: Egg Thieves and Damned Audubonites, 42 Hatching Bird Watchers, 53 The Fight For Sight (Records), 55 Bird Watching at Cornell, 57 Chapter Two: Collecting the Sounds of Nature, 61 Introduction, 61 Technology and Techniques, 65 The Network: Centers of Collection, 70 The Network: Sound Recorders, 71 Experiencing the Network: The Stillwells and Kellogg, 78 Experiencing the Network: Road Trip!, 79 Managing the Network, 80 Listening to the Sounds -

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by O Number 414 Thu Axmucanmuum"Ne Okcitynatural HITORY March 24, 1930

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by o Number 414 THu AxmucANMuum"Ne okCityNATURAL HITORY March 24, 1930 59.82 (728.1) STUDIES FROM THE DWIGHT COLLECTION OF GUATEMALA BIRDS. II BY LUDLOW GRISCOM This is the second' preliminary paper, containing descriptions of new forms in the Dwight Collection, or revisions of Central American birds, based almost entirely on material in The American Museum of Natural History. As usual, all measuremenits are in millimeters, and technical color-terms follow Ridgway's nomenclature. The writer would appreciate prompt criticism from his colleagues, for inclusion in the final report. Cerchneis sparveria,tropicalis, new subspecies SUBSPECIFIC CHARACTERS.-Similar to typical Cerchneis sparveria (Linnleus) of "Carolina," but much smaller and strikingly darker colored above in all ages and both sexes; adult male apparently without rufous crown-patch and only a faint tinge of fawn color on the chest; striping of female below a darker, more blackish brown; wing of males, 162-171, of females, 173-182; in size nearest peninularis Mearns of southern Lower California, which, however, is even paler than phalena of the southwestern United States. TYPE.-No. 57811, Dwight Collection; breeding male; Antigua, Guatemala; May 20, 1924; A. W. Anthony. MATERIAL EXAMINED Cerchneis sparveria spar'eria.-Several hundred specimens from most of North America, e.tern Mexico and Central America, including type of C. s. guatemalenis Swann from Capetillo, Guatemala. Cerchneis sparveria phalkna.-Over one hundred specimens from the south- western United States and western Mexico south to Durango. Cerchneis sparveria tropicalis.-Guatemala: Antigua, 2 e ad., 1 6" imm., 2 9 ad., 1 9 fledgeling. -

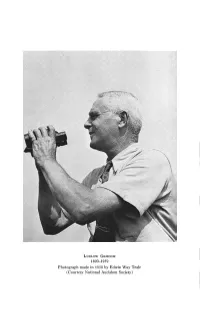

Ludlow Griscom

LUl)LOW GRxsco•r 1890-1959 Photograph made in 1950 by Edwin Way Teale (Courtesy National Audubon Society) IN MEMORIAM: LUDLOW GRISCOM ROGER T. PETERSON T•osE of us who might be called seniorornithologists recognize that Ludlow Griscomsymbolized an era, the rise of the competentbird- watcher.It washe, perhapsmore than anyoneelse, who bridgedthe gap betweenthe collectorof the old schooland the modernfield ornithologist with the binocular.He demonstratedthat practicallyall birdshave their field marksand that it is seldomnecessary for a trainedman to shoot a bird to know,at the specificlevel, precisely what it is. Like so many brilliant field birders, Ludlow Griscomwas born and raisedin New York City. He was born on June 17, 1890. His parents were ClementActon and GenevieveSprigg Griscom, who took him almost every summer on motoring trips through Europe. Growing up in an internationalatmosphere (his grandfatherwas a general,an uncle was an admiral, and anotheruncle an ambassador),he becamea linguist at an early age. He was taught by private tutors until he was 11 and then attendedthe SymesSchool where at the age of 15 he passedthe entrance examinationsfor Harvard. Being too young, he was kept at home for two more years where he devotedmost of his time to music and languages.In fact, he becameso skilled at the keyboard that he entertainedthe thought of becominga concertpianist. However, his interestin birds,sparked at the age of 6, had by now gainedascendancy over the piano,much to the disapprovalof his parents,who felt he was wasting his time. At the age of 17 he enrolledat ColumbiaUniversity where he took a pre-law course.Because of his family backgroundand fabulouslinguistic ability (he learnedto speak5 languagesfluently, could read 10 easily, and could translateup to 18 with a little help), his parentsinsisted that he preparefor the foreignservice, but he would have none of this. -

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by Number 159 the AMERICAN MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY Feb

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by Number 159 THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Feb. 16, 1925 New York City 59.82(728) DESCRIPTIONS OF NEW BIRDS FROM NICARAGUA BY W. DEW. MILLER AND LUDLOW GRISCOM After unavoidable delay we have been able to resurne work on our Nicaraguan collections, and it seems advisable at this time to submit descriptions of new species and subspecies for criticism, pending the appearance of the completed report. We are particularly indebted to Doctor J. Dwight for the privilege of using his series of beautifully prepared Costa Rican skins for compari- son, and our acknowledgments are also due Doctor Richmond of the U. S. National Museum and the authorities of the Biological Survey for the privilege of comparing some of our material with specimens in the collections in their respective institutions. Measurements, unless otherwise stated, are in millimeters, and color terms are taken from Ridgway's 'Color Standards and Color Nomen- clature.' Nyctiphrynus lautus, new species SPECIFIC CHARACTERS.-Most nearly related to N. ocellatus (Tschudi) of Ama- zonia but much smaller (wing and tail nearly a half inch shorter); feathers of pileum and occiput about evenly vermiculated with blackish and tawny, instead of largely black with ochraceous-buff vermiculations; ground color of upperparts, wings and tail more richly colored, tawny or rufous chestnut, instead of rufous brown or choco- late-brown, most pronounced on the wing-coverts and scapulars; velvety spots on scapulars greatly reduced in number, about one half as -

Presidential Birders

Presidential Birders a special publication from , FDR Bird Watcher As the biographer Jean Edward Smith notes in his preface to FDR, “there is little that has not been said, some- where, about the president.” Yet his lifelong fascination with bird watching is often overlooked, a dimension that reveals something about FDR the man. It is well known that Theodore Roosevelt, a distant cousin of Franklin’s, was an accomplished naturalist and a skilled birder. While president, TR kept a yard list of the birds he saw and heard around the White House: an impressive 93 spe- cies, including a pair of saw-whet owls. Franklin idolized his elder cousin Ted, emulating him in every respect, down to wearing nearly identical pince-nez eyeglasses. It may not be too great a leap to assume that it was TR’s interest in bird watching that inspired young FDR to pursue the hobby himself. KYLE CARLSEN K YLE C ARLSEN 44 birdwatchersdigest.com • JANUARY/FEBRUARY ’15 • BIRD WATCHER’S DIGEST Springwood, FDR’s home on the Hudson River. A 45 FDR, center, joins the May Census on May 10, 1942. Left to right: Ray Guernsey, Allen Frost, Roosevelt, Daisy Suckley, Ludlow Griscom. A shy and curious youngster, came a strict condition: He was Franklin spent a fair amount to take only one bird per species, of his childhood exploring the and never during nesting season. fields, swamps, and woodlands Over the next few years Franklin surrounding Springwood, his built up an impressive collection family’s estate, situated along of birds, ranging from magno- the Hudson River in Hyde Park, lia warbler to red-shouldered New York. -

American Ornithologists' Union / Cooper

AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS’ UNION / COOPER ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2013 12-17 August 2013 Chicago, Illinois Hosted by: CONTENTS Welcome from John Bates, AOU/COS 2013 Local Committee Chair ............................ 3 Conference Organizers & Committees ....................................................................... 4-5 AOU/COS 2013 General Information ......................................................................... 6-11 Registration & Information ................................................................................ 6-7 Social & Special Events ...................................................................................... 8-9 Field Trips .......................................................................................................... 11 Council & Business Meetings ..................................................................................... 12 Workshops ................................................................................................................ 12 General Schedule ....................................................................................................... 13-14 Abstracts – Online login Information ......................................................................... 14 Presentation Guidelines for Oral & Poster Presentations ........................................... 14-15 Exhibitors ................................................................................................................... 15 Sponsors ................................................................................................................... -

Table of Contents

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 35, 1953-1954 TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFICERS...............................................................................................5 OFFICERS, 1905-1955.............................................................................7 PAPERS EARLY HISTORY OF CAMBRIDGE ORNITHOLOGY......................................11 BY LUDLOW GRISCOM THE CAMBRIDGE PLANT CLUB................................................................17 BY LOIS LILLEY HOWE, MARION JESSIE DUNHAM, MRS. ROBERT GOODALE, MARY B. SMITH, AND EDITH SLOAN GRISCOM THE AGASSIZ SCHOOL..........................................................................35 BY EDWARD WALDO FORBES FORTY YEARS IN THE FOGG MUSEUM......................................................57 BY LAURA DUDLEY SAUNDERSON CAMBRIDGEPORT, A BRIEF HISTORY......................................................79 BY JOHN W. WOOD PAGES FROM THE HISTORY OF THE CAMBRIDGE HIGH AND LATIN SCHOOL...............................................91 BY CECIL THAYER DERRY I, TOO, IN ARCADIA..............................................................................111 BY DAVID T. POTTINGER ANNUAL REPORTS.....................................................................................125 MEMBERS...................................................................................................133 THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY PROCEEDINGS FOR THE YEARS 1953-54 LIST OF OFFICERS FOR THESE TWO YEARS President: Hon. Robert Walcott Vice Presidents: Miss -

Bird Observer

Bird Observer VOLUME 43, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2015 HOT BIRDS On January 6, Paul Peterson reported a Black-backed Woodpecker at Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston. It was seen regularly through the end of January. Eduardo del Solar took the photo on the left. On March 1, Suzanne Sullivan was scanning King’s Beach on the Swampscott/Lynn line and spotted a Mew Gull (Kamchatka) among the Ring-billed Gulls. She took the photo above. More Mew Gulls were reported subsequently at the same location. TABLE OF CONTENTS BIRDING AND BOTANIZING THE HAWLEY BOG Robert Wood 81 REMEMBERING HERMAN D’ENTREMONT Glenn d’Entremont 87 A GOOD DAY AT CAPE ANN Herman D’Entremont 89 A COMMEMORATION OF BIRDERS AT MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Regina Harrison 92 BIRDS OF THE WORLD: A NEW EXHIBIT AT THE HARVARD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Maude Baldwin 98 PHOTO ESSAY Birds of the World 104 FIELD NOTES A Hawk in Pigeon’s Clothing David Sibley 106 A Barn Owl in Concord Cole Winstanley and Jalen Winstanley 107 MUSINGS FROM THE BLIND BIRDER Song of Spring Martha Steele 111 GLEANINGS Serendipity and Science David M. Larson 114 ABOUT BOOKS Making it Big Mark Lynch 117 BIRD SIGHTINGS November/December 2014 122 ABOUT THE COVER: Northern Shoveler William E. Davis, Jr. 135 ABOUT THE COVER ARTIST: Barry Van Dusen 136 AT A GLANCE February 2015 Wayne R. Petersen 137 Bird Observer has a new website! http://www.birdobserver.org. Subscribers wishing to have access to online issues should email <[email protected]> for a new password. BIRD OBSERVER Vol. -

A Lifetime of CBC Adventures

© American Museum of Natural History AA LifetimeLifetime ofof CBCCBC Adventures Adventures It began for me in 1934, when I was 16. It was the day after Christmas, and my neighbor Clinton Reynolds and I thought it would be interesting (and fun) to conduct an Audubon Christmas Bird Census (CBC) in our home town of Belmont, Massachusetts. One count had been taken in this same area by Ralph Hoffman, the author of our favorite field guide, in 1900, the very first year of Frank Chapman’s CBC program. My dad had taken 13 CBCs in Massachusetts from 1906 to 1910, generally in the company of a relative or friend, but none had been published from Belmont since 1916. Chandler S. Robbins USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center Laurel, MD 20708-4039 [email protected] Chandler S. Robbins recently retired after 60 years of service with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at the Patuxent Research Center in Maryland. In addition to his research into the effects of DDT on birds, he co-authored Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia, worked on Midway Atoll on the Navy’s birds- versus-aircraft problems, and started Operation Recovery, a cooperative bird-banding program along the Atlantic Coast. As part of the North American Breeding Bird Survey, which he co-initiated in 1966, he has been monitoring continental breeding bird populations for 40 years. In the 1980s, and again in the past five years, Robbins has been heavily involved in breeding bird atlas studies, especially those in Maryland. 10 AMERICAN BIRDS “I recall one tally when the report of a Dovekie was questioned by other participants—until the observer reached into a coat pocket and pulled out the live bird!” —Chan Robbins Facing page: Frank M. -

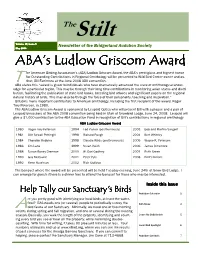

ABA's Ludlow Griscom Award ABA's Ludlow Griscom Award

The Stilt Volume 37, Issue 5 Newsletter of the Bridgerland Audubon Society May 2008May 2008 ABA’s Ludlow Griscom Award he American Birding Association’s (ABA) Ludlow Griscom Award, the ABA’s prestigious and highest honor for Outstanding Contributions in Regional Ornithology will be presented to Wild Bird Center owner and au- TTT thor, Bill Fenimore at the June 2008 ABA convention. ABA states this “award is given to individuals who have dramatically advanced the state of ornithological knowl- edge for a particular region. This may be through their long-time contributions in monitoring avian status and distri- bution, facilitating the publication of state bird books, breeding bird atlases and significant papers on the regional natural history of birds. This may also be through the force of their personality, teaching and inspiration.” Bill joins many important contributors to American ornithology, including the first recipient of the award, Roger Tory Peterson, in 1980. The ABA Ludlow Griscom Award is sponsored by Leupold Optics who will present Bill with a plaque and a pair of Leupold binoculars at the ABA 2008 convention being held in Utah at Snowbird Lodge, June 24, 2008. Leupold will give a $1,000 contribution to the ABA Education Fund in recognition of Bill’s contributions in regional ornithology. ABA Ludlow Griscom Award 1980 Roger Tory Peterson 1994 Ted Parker (posthumously) 2003 Bob and Martha Sargent 1981 Olin Sewall Pettingill 1996 Richard Pough 2004 Bret Whitney 1984 Chandler Robbins 1998 Claudia Wilds (posthumously) 2005 Wayne R. Petersen 1986 Jim Lane 1999 Stuart Keith 2006 James Dinsmore 1988 Susan Roney Drennan 2000 W.