View Pdf of Printed Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excavating the Wolastoqiyik Language

1 (Submitted to Wulustuk Times, January 2012) EXCAVATING THE WOLASTOQIYIK LANGUAGE Mareshites, Marasheete, Malecite, Amalecite, Malecetes, Ma'lesit, Maleshite, Malicetes, Malisit, Maleschite and many more spellings. So many variations of one name. The Maliseets, as we refer to them today, never called themselves by that name before the white man came here. It was assigned to them by others. The first recording of the name was by Gov. Villebon at Fort Naxouat (Nashwaak) in a letter to Monsieur Jean- 2 Baptiste de Lagny (France's intendant of Commerce), Sept 2, 1694 in which he describes their territory: The Malicites begin at the river St. John, and inland as far as la Riviere du Loup, and along the sea shore, occupying Pesmonquadis, Majais, les Monts Deserts and Pentagoet, and all the rivers along the coast. At Pentagoe't, among the Malicites, are many of the Kennebec Indians. Taxous [aka Moxus] was the principal chief of the river Kinibeguy, but having married a woman of Pentagoet, he settled there with her relations. As to Matakando he is a Malicite. [Madockawando was an adopted brother of Moxus. In 1694 he was Chief on the Wolastoq] Over the years there have been various explanations of the proper spelling and origin of this word. Vincent Erickson wrote in the "Handbook of North American Indians" that the name Maliseet "appears to have been given by the neighboring Micmac to whom the Maliseet language sounded like faulty Micmac; the word 'Maliseet' may be glossed 'lazy, poor or bad speakers.' " Similarly Montague Chamberlain, in his Maliseet Vocabulary published in 1899, suggested that it was derived from the Micmac name Malisit, "broken talkers"; John Tanner in 1830 gives the form as Mahnesheets, meaning "slow tongues" and states he was given that name by a "native." In 1878 R. -

English Settlement Before the Mayhews: the “Pease Tradition”

151 Lagoon Pond Road Vineyard Haven, MA 02568 Formerly MVMUSEUM The Dukes County Intelligencer NOVEMBER 2018 VOLUME 59 Quarterly NO. 4 Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s Journal of Island History MVMUSEUM.ORG English settlement before the Mayhews: Edgartown The “Pease Tradition” from the Sea Revisited View from the deck of a sailing ship in Nantucket Sound, looking south toward Edgartown, around the American Revolution. The land would have looked much the same to the first English settlers in the early 1600s (from The Atlantic Neptune, 1777). On the Cover: A modern replica of the Godspeed, a typical English merchant sailing ship from the early 1600s (photo by Trader Doc Hogan). Also in this Issue: Place Names and Hidden Histories MVMUSEUM.ORG MVMUSEUM Cover, Vol. 59 No. 4.indd 1 1/23/19 8:19:04 AM MVM Membership Categories Details at mvmuseum.org/membership Basic ..............................................$55 Partner ........................................$150 Sustainer .....................................$250 Patron ..........................................$500 Benefactor................................$1,000 Basic membership includes one adult; higher levels include two adults. All levels include children through age 18. Full-time Island residents are eligible for discounted membership rates. Contact Teresa Kruszewski at 508-627-4441 x117. Traces Some past events offer the historians who study them an embarrassment of riches. The archives of a successful company or an influential US president can easily fill a building, and distilling them into an authoritative book can consume decades. Other events leave behind only the barest traces—scraps and fragments of records, fleeting references by contemporary observers, and shadows thrown on other events of the time—and can be reconstructed only with the aid of inference, imagination, and ingenuity. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

r Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung Under section 501(c), LOOL benefit trust or private foundation) Department or me Ti2asury Internal Revenue Service 1 The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements A For the 2002 calendar year, or tax year period beginning APR 1 2002 and i MAR 31, 2003 B Check if Please C Name of organization D Employer identification number use IRS nddmss label or [::]change print or HE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS 04-2105780 ~changa s~ Number and street (or P.0 box if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number =Initial return sPecisc572 ESSEX STREET 978 921-1944 Final = City or town, state or country, and ZIP +4 F Pccoun6npmethad 0 Cash [K] Accrual return Other =Amended~'d~° [BEVERLY , MA 01915 licatio" ~ o S ~~ . El Section 501(c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. :'dl°° must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ) . H(a) Is this a group retain for affiliates ~ Yes OX No G web site: OWW " THETRUSTEES . ORG H(b) It 'Yes,' enter number of affiliates 10, J Organization type (cnakonly one) " OX 501(c) ( 3 ) 1 (Insert no) = 4947(a)(1) or = 52 H(c) Are all affiliates inciuded9 N/A 0 Yes 0 No (If -NO,- attach a list ) K Check here " 0 if the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 . -

Cape Poge Wildlife Refuge, Leland Beach, Wasque Point, and Norton Point Beach Edgartown

Impact Avoidance and Minimization Plan: Cape Poge Wildlife Refuge, Leland Beach, Wasque Point, and Norton Point Beach Edgartown, Martha’s Vineyard January 2020 The Trustees of Reservations 200 High Street Boston, MA 02110 Table of Contents 1. Site Description 1.a Maps……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 1.b Description of site…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 1.c habitat and management………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 1.d Plover breeding a productivity………………………………………………………..…………………….. 6 2. Responsible Staff 2.a Staff biographies……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 3. Beach Management 3.a.i Recreational Activities………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 3.a.ii Parking and Roads……………………………………………………………………………………….……. 9 3.a.iii Beach cleaning and refuse management…………………………………..……………………. 10 3.a.iv Rules and regulations…………………………………………………………………………….……….... 10 3.a.v Law enforcement…………………………………………………………………………….………………… 10 3.a.vi Other management……………………………………………………………………………………………. 10 3.a.vi Piping plover management……………………………………………………………………………….. 10 4. Covered Activities 4.1.a OSV use in vicinity of piping plover chicks…………………………………………………………….. 12 4.1.b Reduced symbolic fencing……………………………………………………………………………………. 15 4.1.c Reduced proactive symbolic fencing……………………………………………………………………… 16 4.2 Contingency Plan…………………………………………………………………………………….……………. 18 4.3 Violations………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 4.4 Self-escort program reporting………………………………………………………………………………… 18 5. Budget…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Bird Watcher's General Store

BIRD OBSERVER BIRD OBSERVER ^4^ ■ ^ '- V - iIRDOBSEl jjjijdOBSEKSK fi« o , bs«s^2; bird observer ®^«D 0BS£, VOL. 21 NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 BIRD OBSERVER • s bimonthly {ournal • To enhance understanding, observation, and enjoyment of birds. VOL. 21, NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 Editor In Chief Corporate Officers Board of Directors Martha Steele President Dorothy R. Arvidson Associate Editor William E. Davis, Jr. Alden G. Clayton Janet L. Heywood Treasurer Herman H. D'Entremont Lee E. Taylor Department Heads H. Christian Floyd Clerk Cover Art Richard A. Forster Glenn d'Entremont William E. Davis, Jr. Janet L. Heywood Where to Go Birding Subscription Manager Harriet E. Hoffman Jim Berry David E. Lange John C. Kricher Feature Articles and Advertisements David E. Lange Field Notes Robert H. Stymeist John C. Kricher Simon Perkins Book Reviews Associate Staff Wayne R. Petersen Alden G. Clayton Theodore Atkinson Marjorie W. Rines Bird Sightings Martha Vaughan John A. Shetterly Robert H. Stymeist Editor Emeritus Martha Steele At a Glance Dorothy R. Arvidson Robert H. Stymeist Wayne R. Petersen BIRD OBSERVER {USPS 369-850) is published bimonthly, COPYRIGHT © 1993 by Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts, Inc., 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178, a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation under section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Gifts to Bird Observer will be greatly appreciated and are tax deductible. POSTMASTER; Send address changes to BIRD OBSERVER, 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $16 for 6 issues, $30 for two years in the U. S. Add $2.50 per year for Canada and foreign. Single copies ^ .0 0 . -

GO Pass User Benefits at Trustees Properties with an Admission Fee

GO Pass User Benefits at Trustees Properties with an Admission Fee Trustees Property Non-Member Admission Member Admission GO Pass Admission Appleton Grass Rides $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Ashley House $5 House Tour/Grounds Free Free Free Bartholomew’s Cobble $5 Adult/ $1 Child (6-12) + $5 Free Free + $5 Parking Kiosk Parking Kiosk Bryant Homestead $5 General House Tour Free Free Cape Poge $5 Adult/ Child 15 and under free Free Free Castle Hill* $10 Grounds + Tour Admission Grounds Free/Discounted Tours Grounds Free/ Discounted Tours Chesterfield Gorge $2 Free Free Crane Beach* Price per car/varies by season Up to 50% discounted admission Up to 50% discounted admission Fruitlands Museum $14 Adult/Child $6 Free Free Halibut Point $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR Free (display card on dash) $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR Little Tom Mountain $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR Long Point Beach $10 Per Car + $5 Per Adult Free Admission + 50% off Parking Free Admission + 50% off Parking Misery Island – June thru Labor $5 Adult/ $3 Child Free Free Day Mission House $5 Free Free Monument Mountain $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Naumkeag $15 Adult (age 15+) Free Free Notchview – on season skiing $15 Adult/ $6 Child (6-12) Wknd: $8 A/ $3 C | Wkdy: Free Wknd: $8 A/ $3 C | Wkdy: Free Old Manse $10 A/ $5 C/ $9 SR+ST/ $25 Family Free Free Rocky Woods $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Ward Reservation $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Wasque – Memorial to Columbus $5 Parking + $5 Per Person Free Free World’s End $6 Free Free *See separate pricing sheets for detailed pricing structure . -

Birdobserver7.2 Page52-60 a Guide to Birding on Martha's

A GUIDE TO BIRDING ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD Richard M. Sargent, Montclair, New Jersey A total of 35T species have been recorded on Martha’s Vineyard, This represents 85 per cent of all the hirds recorded in the state of Massa- chusetts, Prohably the Most faMous of theM, excluding the now extinct Heath Hen, was the Eurasian Curlew, first identified on February I8, 1978» and subsequently seen by several hundred birders during the Month that it reMained "on location." Of the 357 species, approxiMately 275 are regular, occuring annually. The variety of species present and the overall charM of the Vineyard Make it a fun place to bird. The Island is reached by ferry froM Woods Hole and if you plan to tahe your car it is very advisable, if not a necessity, to Make advance res- ervations with the SteaMship Authority for both in-season and out-of~ season trips. And heré a note of caution: Much of the property around the ponds and access to Many of the back areas is private property and posted. The areas discussed in this article are open to the public and offer a good cross-section of Vineyard birding areas. If there are private areas you want to cover, be sure to obtain perMission before entering them. The Vineyard is roughly triangular in shape with the base of the triangle twenty Miles, east to west, and the height, north to south, ten Miles. It is of glacial origin with Much of the north shore hilly and forMed by glacial Morain. To the south there are broad, fíat outwash plains cut by Many fresh water or brackish ponds separated froM the ocean by bar- rier beaches, Probably the best tiMe to bird the Vineyard is the Month of SepteMber. -

Early Birding Book

Early Birding in Dutchess County 1870 - 1950 Before Binoculars to Field Guides by Stan DeOrsey Published on behalf of The Ralph T. Waterman Bird Club, Inc. Poughkeepsie, New York 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Stan DeOrsey All rights reserved First printing July 2016 Digital version June 2018, with minor changes and new pages added at the end. Digital version July 2019, pages added at end. Cover images: Front: - Frank Chapman’s Birds of Eastern North America (1912 ed.) - LS Horton’s post card of his Long-eared Owl photograph (1906). - Rhinebeck Bird Club’s second Year Book with Crosby’s “Birds and Seasons” articles (1916). - Chester Reed’s Bird Guide, Land Birds East of the Rockies (1908 ed.) - 3x binoculars c.1910. Back: 1880 - first bird list for Dutchess County by Winfrid Stearns. 1891 - The Oölogist’s Journal published in Poughkeepsie by Fred Stack. 1900 - specimen tag for Canada Warbler from CC Young collection at Vassar College. 1915 - membership application for Rhinebeck Bird Club. 1921 - Maunsell Crosby’s county bird list from Rhinebeck Bird Club’s last Year Book. 1939 - specimen tag from Vassar Brothers Institute Museum. 1943 - May Census checklist, reading: Raymond Guernsey, Frank L. Gardner, Jr., Ruth Turner & AF [Allen Frost] (James Gardner); May 16, 1943, 3:30am - 9:30pm; Overcast & Cold all day; Thompson Pond, Cruger Island, Mt. Rutson, Vandenburg’s Cove, Poughkeepsie, Lake Walton, Noxon [in LaGrange], Sylvan Lake, Crouse’s Store [in Union Vale], Chestnut Ridge, Brickyard Swamp, Manchester, & Home via Red Oaks Mill. They counted 117 species, James Gardner, Frank’s brother, added 3 more. -

Bird Watchers and the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology a Thesis S

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE LISTENING AT THE LAB: BIRD WATCHERS AND THE CORNELL LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE By JACKSON RINN POPE III Norman, Oklahoma 2016 LISTENING AT THE LAB: BIRD WATCHERS AND THE CORNELL LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF SCIENCE BY ______________________________ Dr. Katherine Pandora, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Piers Hale ______________________________ Dr. Stephen Weldon ______________________________ Dr. Zev Trachtenberg © Copyright by JACKSON RINN POPE III 2016 All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction, 1 Brief History of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 3 Chapter Overview, 7 Historiography, 10 Bird Watching and Ornithology, 10 Observational Science and Amateur Participation, 23 Natural History and New Media, 31 Chapter One: Collection, Conservation, and Community, 35 Introduction, 35 The Culture of Collecting, 36 Cultural Conflict: Egg Thieves and Damned Audubonites, 42 Hatching Bird Watchers, 53 The Fight For Sight (Records), 55 Bird Watching at Cornell, 57 Chapter Two: Collecting the Sounds of Nature, 61 Introduction, 61 Technology and Techniques, 65 The Network: Centers of Collection, 70 The Network: Sound Recorders, 71 Experiencing the Network: The Stillwells and Kellogg, 78 Experiencing the Network: Road Trip!, 79 Managing the Network, 80 Listening to the Sounds -

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by O Number 414 Thu Axmucanmuum"Ne Okcitynatural HITORY March 24, 1930

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by o Number 414 THu AxmucANMuum"Ne okCityNATURAL HITORY March 24, 1930 59.82 (728.1) STUDIES FROM THE DWIGHT COLLECTION OF GUATEMALA BIRDS. II BY LUDLOW GRISCOM This is the second' preliminary paper, containing descriptions of new forms in the Dwight Collection, or revisions of Central American birds, based almost entirely on material in The American Museum of Natural History. As usual, all measuremenits are in millimeters, and technical color-terms follow Ridgway's nomenclature. The writer would appreciate prompt criticism from his colleagues, for inclusion in the final report. Cerchneis sparveria,tropicalis, new subspecies SUBSPECIFIC CHARACTERS.-Similar to typical Cerchneis sparveria (Linnleus) of "Carolina," but much smaller and strikingly darker colored above in all ages and both sexes; adult male apparently without rufous crown-patch and only a faint tinge of fawn color on the chest; striping of female below a darker, more blackish brown; wing of males, 162-171, of females, 173-182; in size nearest peninularis Mearns of southern Lower California, which, however, is even paler than phalena of the southwestern United States. TYPE.-No. 57811, Dwight Collection; breeding male; Antigua, Guatemala; May 20, 1924; A. W. Anthony. MATERIAL EXAMINED Cerchneis sparveria spar'eria.-Several hundred specimens from most of North America, e.tern Mexico and Central America, including type of C. s. guatemalenis Swann from Capetillo, Guatemala. Cerchneis sparveria phalkna.-Over one hundred specimens from the south- western United States and western Mexico south to Durango. Cerchneis sparveria tropicalis.-Guatemala: Antigua, 2 e ad., 1 6" imm., 2 9 ad., 1 9 fledgeling. -

Ludlow Griscom

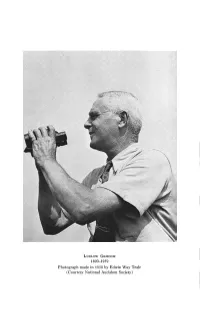

LUl)LOW GRxsco•r 1890-1959 Photograph made in 1950 by Edwin Way Teale (Courtesy National Audubon Society) IN MEMORIAM: LUDLOW GRISCOM ROGER T. PETERSON T•osE of us who might be called seniorornithologists recognize that Ludlow Griscomsymbolized an era, the rise of the competentbird- watcher.It washe, perhapsmore than anyoneelse, who bridgedthe gap betweenthe collectorof the old schooland the modernfield ornithologist with the binocular.He demonstratedthat practicallyall birdshave their field marksand that it is seldomnecessary for a trainedman to shoot a bird to know,at the specificlevel, precisely what it is. Like so many brilliant field birders, Ludlow Griscomwas born and raisedin New York City. He was born on June 17, 1890. His parents were ClementActon and GenevieveSprigg Griscom, who took him almost every summer on motoring trips through Europe. Growing up in an internationalatmosphere (his grandfatherwas a general,an uncle was an admiral, and anotheruncle an ambassador),he becamea linguist at an early age. He was taught by private tutors until he was 11 and then attendedthe SymesSchool where at the age of 15 he passedthe entrance examinationsfor Harvard. Being too young, he was kept at home for two more years where he devotedmost of his time to music and languages.In fact, he becameso skilled at the keyboard that he entertainedthe thought of becominga concertpianist. However, his interestin birds,sparked at the age of 6, had by now gainedascendancy over the piano,much to the disapprovalof his parents,who felt he was wasting his time. At the age of 17 he enrolledat ColumbiaUniversity where he took a pre-law course.Because of his family backgroundand fabulouslinguistic ability (he learnedto speak5 languagesfluently, could read 10 easily, and could translateup to 18 with a little help), his parentsinsisted that he preparefor the foreignservice, but he would have none of this. -

Summer 2005-A

Nipon (It is Summer) HBMI Natural Resources Department HBMI Natural Resources NON-PROFIT ORG June 2005 U.S. POSTAGE Brenda Commander - Tribal Chief Department PAID Susan Young - Editor PERMIT #2 Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians HOULTON ME This newsletter is 88 Bell Road printed on Recycled Littleton, ME 04730 chlorine free paper Phone: 207-532-4273 Skitkomiq Nutacomit Fax: 207-532-6883 Earth Speaker Wabanaki Alternatives to DEET Inside this issue: Each year just as the others feel by using DEET products Alternatives to DEET…………. 1 weather turns nice here in you are “spreading poison on your Skywatching - Meteor Showers... 2 Northern Maine the black skin”. Whatever your feelings are about Meteor Watching Tips………… 2 flies, mosquitoes, midges, DEET there are alternatives available. no-see-ums, horse and deer flies awaken If you choose to use commercial repel- Slow Down There’s Moose to drive us indoors or straight to the lents including DEET etc., please refer Around………………………... insect repellent. But which one should to the precautions listed on page 6 to Envirothon 2005 ……………… 3 you use? Ask twenty people and you’ll help you use them safely. Meet the Summer Techs ……… 4 get at least twenty answers. Word Search Puzzle …………... 4 There is a natural alternative to some of these DEET products produced by Maine’s 11 Most Un-Wanted Years ago in some parts of the country, Aquatic Plants ………………… when mosquito season started, states and a Maliseet-Passamaquoddy woman named Alison Lewy. Her product Avoiding Ticks & Lyme Disease. 6 towns, employed sprayer trucks to drive through the neighborhoods spraying Lewey’s Eco-Blend is a 100% natural Using Insect Repellents Safely .