Inventing the Birdwatching Field Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisdom in the Thanksgiving Season: 64-Year Old Laysan Albatross Is

Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge/Battle of Midway National Memorial Box 50167 Honolulu, HI 96850 Phone: 808-954-4817 http://www.fws./gov/refuge/Midway-Atoll \ November 26, 2015 Contact: Bret Wolfe 808-954-4817 Email: [email protected] Wisdom in the Thanksgiving Season: 64-year old Laysan albatross is sighted on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge The world’s oldest known seabird returns and finds her mate! U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officials are pleased to announce that the world’s oldest known banded bird in the wild, a Laysan albatross named Wisdom, was sighted on November 19 on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge within Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Just in time for the special day of giving thanks, Wisdom was spotted with her mate amongst the world’s largest nesting albatross colony. “In the face of dramatic seabird population decreases worldwide –70% drop since the 1950’s when Wisdom was first banded–Wisdom has become a symbol of hope and inspiration,” said Refuge Manager, Dan Clark.” We are a part of the fate of Wisdom and it is gratifying to see her return because of the decades of hard work conducted to manage and protect albatross nesting habitat.” “Wisdom left soon after mating but we expect her back any day now to lay her egg,” noted Deputy Refuge Manager, Bret Wolfe. “It is very humbling to think that she has been visiting Midway for at least 64 years. Navy sailors and their families likely walked by her not knowing she could possibly be rearing a chick over 50 years later. -

Contents News and Announcements

Newsletter of the International Working Group of Partners in Flight No 62 A Hemisphere-wide bird conservation initiative. August – September 2006 Sponsored by: US Fish and Wildlife Service. Produced by: International Working Group of Partners in Flight CONTENTS News and Announcements • Rainforest Alliance offers Free, Online Reference to Promote Western Hemisphere Migratory Species Conservation • Parrot Conservation Campaign in Ecuador • Information on Wintering Purple Martins Needed • Building Migratory Bridges Program in Panama • 2006 Biotropica Award for Excellence in Tropical Biology and Conservation • Hornero available on line • PIFMESO honors Dr. Chandler Robbins • New Bird Discovered next to Cerulean Warbler Bird Reserve • Marvelous Spatuletail Protected by Conservation Easement in Peru • Andean Welcome for Migratory Birds this October Web News Funding Training / Job Opportunities Meetings Publications Available Recent Literature NEWS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS RAINFOREST ALLIANCE OFFERS FREE, ONLINE REFERENCE TO PROMOTE WESTERN HEMISPHERE MIGRATORY SPECIES CONSERVATION A free online reference is now available to wildlife managers and conservationists working to conserve migratory species in the Western Hemisphere. The Rainforest Alliance’s Migratory Species Pathway offers detailed information in English and Spanish about more than 50 initiatives to conserve migratory species in the Americas and the Caribbean, along with interviews and advice from conservation leaders. With support from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service’s International Division, the Rainforest Alliance took on the challenge of creating a space on the Internet where the migratory species conservation community could easily come together to share information. The new Pathway features a "Projects and Tools" section, which includes a list of specific needs identified at the first Western Hemisphere Migratory Species Conference, held in Chile in 2003. -

Bird Watcher's General Store

BIRD OBSERVER BIRD OBSERVER ^4^ ■ ^ '- V - iIRDOBSEl jjjijdOBSEKSK fi« o , bs«s^2; bird observer ®^«D 0BS£, VOL. 21 NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 BIRD OBSERVER • s bimonthly {ournal • To enhance understanding, observation, and enjoyment of birds. VOL. 21, NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 Editor In Chief Corporate Officers Board of Directors Martha Steele President Dorothy R. Arvidson Associate Editor William E. Davis, Jr. Alden G. Clayton Janet L. Heywood Treasurer Herman H. D'Entremont Lee E. Taylor Department Heads H. Christian Floyd Clerk Cover Art Richard A. Forster Glenn d'Entremont William E. Davis, Jr. Janet L. Heywood Where to Go Birding Subscription Manager Harriet E. Hoffman Jim Berry David E. Lange John C. Kricher Feature Articles and Advertisements David E. Lange Field Notes Robert H. Stymeist John C. Kricher Simon Perkins Book Reviews Associate Staff Wayne R. Petersen Alden G. Clayton Theodore Atkinson Marjorie W. Rines Bird Sightings Martha Vaughan John A. Shetterly Robert H. Stymeist Editor Emeritus Martha Steele At a Glance Dorothy R. Arvidson Robert H. Stymeist Wayne R. Petersen BIRD OBSERVER {USPS 369-850) is published bimonthly, COPYRIGHT © 1993 by Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts, Inc., 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178, a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation under section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Gifts to Bird Observer will be greatly appreciated and are tax deductible. POSTMASTER; Send address changes to BIRD OBSERVER, 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $16 for 6 issues, $30 for two years in the U. S. Add $2.50 per year for Canada and foreign. Single copies ^ .0 0 . -

Annual Report Edition from the PRESIDENT’S DESK

SUMMER 2017 Annual Report Edition FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK am so excited about this Newsletter! I This issue represents our Annual NH AUDUBON Report edition where we share the wide diversity of your impact on the work we BOARD OF TRUSTEES Michael Amaral, Vice Chair, Warner accomplish each year. We feel enormous Louis DeMato, Treasurer, Manchester gratitude for all the volunteers, donors, David Howe, Secretary, Concord foundations, and grants we receive each Tom Kelly, Londonderry Lauren Kras, Merrimack year that support our critical work in Dawn Lemieux, Groton environmental education, conservation Paul Nickerson, Hudson Chris Picotte, Webster science, land management, and advocacy. David Ries, Chair, Warner For example, Larry Sunderland Tony Sayess, Concord Thomas Warren, Dublin represents not only an individual donor who supports our policy work, he is also of our work-force. We applaud their STAFF one of our most loyal donors. Larry’s level of dedication and consistent high Douglas A. Bechtel, President Shelby Bernier, Education Coordinator involvement with NH Audubon spans performance. Next time you see one of Nancy Boisvert, Nature Store Manager 30 years. Thank you Larry, for your these folks, make sure to thank them for Lynn Bouchard, Director of Human Resources support and loyalty! their work, too! Phil Brown, Director of Land Management Another amazing example of support Finally, we recognize two leaders Hillary Chapman, Education Specialist Gail Coffey, Grants Manager comes from the estate of Drs. Lorus in the environmental and Audubon Joseph Consentino, Director of Finance and Margery Milne, both of whom movement that passed this year. Barbara Ian Cullison, Newfound Center Director were acclaimed scientists and authors Day Richards and Chan Robbins were Helen Dalbeck, Amoskeag Fishways Executive Director of their time. -

Early Birding Book

Early Birding in Dutchess County 1870 - 1950 Before Binoculars to Field Guides by Stan DeOrsey Published on behalf of The Ralph T. Waterman Bird Club, Inc. Poughkeepsie, New York 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Stan DeOrsey All rights reserved First printing July 2016 Digital version June 2018, with minor changes and new pages added at the end. Digital version July 2019, pages added at end. Cover images: Front: - Frank Chapman’s Birds of Eastern North America (1912 ed.) - LS Horton’s post card of his Long-eared Owl photograph (1906). - Rhinebeck Bird Club’s second Year Book with Crosby’s “Birds and Seasons” articles (1916). - Chester Reed’s Bird Guide, Land Birds East of the Rockies (1908 ed.) - 3x binoculars c.1910. Back: 1880 - first bird list for Dutchess County by Winfrid Stearns. 1891 - The Oölogist’s Journal published in Poughkeepsie by Fred Stack. 1900 - specimen tag for Canada Warbler from CC Young collection at Vassar College. 1915 - membership application for Rhinebeck Bird Club. 1921 - Maunsell Crosby’s county bird list from Rhinebeck Bird Club’s last Year Book. 1939 - specimen tag from Vassar Brothers Institute Museum. 1943 - May Census checklist, reading: Raymond Guernsey, Frank L. Gardner, Jr., Ruth Turner & AF [Allen Frost] (James Gardner); May 16, 1943, 3:30am - 9:30pm; Overcast & Cold all day; Thompson Pond, Cruger Island, Mt. Rutson, Vandenburg’s Cove, Poughkeepsie, Lake Walton, Noxon [in LaGrange], Sylvan Lake, Crouse’s Store [in Union Vale], Chestnut Ridge, Brickyard Swamp, Manchester, & Home via Red Oaks Mill. They counted 117 species, James Gardner, Frank’s brother, added 3 more. -

Bird Watchers and the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology a Thesis S

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE LISTENING AT THE LAB: BIRD WATCHERS AND THE CORNELL LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE By JACKSON RINN POPE III Norman, Oklahoma 2016 LISTENING AT THE LAB: BIRD WATCHERS AND THE CORNELL LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF SCIENCE BY ______________________________ Dr. Katherine Pandora, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Piers Hale ______________________________ Dr. Stephen Weldon ______________________________ Dr. Zev Trachtenberg © Copyright by JACKSON RINN POPE III 2016 All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction, 1 Brief History of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 3 Chapter Overview, 7 Historiography, 10 Bird Watching and Ornithology, 10 Observational Science and Amateur Participation, 23 Natural History and New Media, 31 Chapter One: Collection, Conservation, and Community, 35 Introduction, 35 The Culture of Collecting, 36 Cultural Conflict: Egg Thieves and Damned Audubonites, 42 Hatching Bird Watchers, 53 The Fight For Sight (Records), 55 Bird Watching at Cornell, 57 Chapter Two: Collecting the Sounds of Nature, 61 Introduction, 61 Technology and Techniques, 65 The Network: Centers of Collection, 70 The Network: Sound Recorders, 71 Experiencing the Network: The Stillwells and Kellogg, 78 Experiencing the Network: Road Trip!, 79 Managing the Network, 80 Listening to the Sounds -

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by O Number 414 Thu Axmucanmuum"Ne Okcitynatural HITORY March 24, 1930

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Published by o Number 414 THu AxmucANMuum"Ne okCityNATURAL HITORY March 24, 1930 59.82 (728.1) STUDIES FROM THE DWIGHT COLLECTION OF GUATEMALA BIRDS. II BY LUDLOW GRISCOM This is the second' preliminary paper, containing descriptions of new forms in the Dwight Collection, or revisions of Central American birds, based almost entirely on material in The American Museum of Natural History. As usual, all measuremenits are in millimeters, and technical color-terms follow Ridgway's nomenclature. The writer would appreciate prompt criticism from his colleagues, for inclusion in the final report. Cerchneis sparveria,tropicalis, new subspecies SUBSPECIFIC CHARACTERS.-Similar to typical Cerchneis sparveria (Linnleus) of "Carolina," but much smaller and strikingly darker colored above in all ages and both sexes; adult male apparently without rufous crown-patch and only a faint tinge of fawn color on the chest; striping of female below a darker, more blackish brown; wing of males, 162-171, of females, 173-182; in size nearest peninularis Mearns of southern Lower California, which, however, is even paler than phalena of the southwestern United States. TYPE.-No. 57811, Dwight Collection; breeding male; Antigua, Guatemala; May 20, 1924; A. W. Anthony. MATERIAL EXAMINED Cerchneis sparveria spar'eria.-Several hundred specimens from most of North America, e.tern Mexico and Central America, including type of C. s. guatemalenis Swann from Capetillo, Guatemala. Cerchneis sparveria phalkna.-Over one hundred specimens from the south- western United States and western Mexico south to Durango. Cerchneis sparveria tropicalis.-Guatemala: Antigua, 2 e ad., 1 6" imm., 2 9 ad., 1 9 fledgeling. -

The Bluebir D

TT H H E E BLUEBIRBLUEBIR DD The voice of ASM since 1934 June 2017 Volume 84, No. 2 The Audubon Society of Missouri Missouri’s Ornithological Society Since 1901 The Audubon Society of Missouri Officers Regional Directors Mark Haas*+, President (2018) Charles Burwick+ (2017) 614 Otto Drive; Jackson MO 63755; Springfield (417) 860-9505 (573) 204-0626 Lottie Bushmann+ (2018) [email protected] Columbia, (573) 445-3942 Louise Wilkinson*+, Vice-President Jeff Cantrell+ (2017) (2018); P.O. Box 804, Rolla, MO 65402- Neosho (471) 476-3311 0804; (573) 578-4695 [email protected] Mike Doyen+ (2017) Rolla (573) 364-0020 Scott Laurent*+, Secretary (2017) 610 W. 46th Street, #103; Kansas City, Allen Gathman+ (2018) MO 64112; (816) 916-5014 Pocahontas (573) 579-5464 [email protected] Brent Galliart+ (2018) Pat Lueders*+, Treasurer (2017) St. Joseph (816) 232-6038 1147 Hawken Pl., St. Louis, MO Greg Leonard+ (2019) 63119; (314) 222-1711 Columbia (573) 443-8263 [email protected] Terry McNeely+ (2019) Honorary Directors Jameson, MO (660) 828-4215 Richard A. Anderson, St. Louis** Phil Wire+ (2019) Nathan Fay, Ozark** Bowling Green (314) 960-0370 Leo Galloway, St. Joseph** Jim Jackson, Marthasville Lisle Jeffrey, Columbia** Chairs Floyd Lawhon, St. Joseph** Bill Clark, Historian Patrick Mahnkey, Forsyth** 3906 Grace Ellen Dr. Rebecca Matthews, Springfield** Columbia, MO 65202 Sydney Wade, Jefferson City** (573) 474-4510 Dave Witten, Columbia** Kevin Wehner, Membership John Wylie, Jefferson City** 510 Ridgeway Ave. Brad Jacobs, 2016 Recipient of the Columbia, MO 65203 Rudolf Bennitt Award (573) 815-0352 [email protected] Jim Jackson, 2012 Recipient of the Rudolf Bennitt Award Dr. -

2015 Annual Report

2015 ANNUAL REPORT . American Bird Conservancy is the Western Hemisphere’s bird conservation specialist—the only organization with a single and steadfast commitment to achieving conservation results for birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. abcbirds.org COVER: Green-headed Tanager by Glenn Bartley . Message from the Chairman and President Board Chair Warren Cooke ABC President George Fenwick Dear ABC friends and supporters: An acquaintance from the business world recently said that what he likes about ABC is our “effective business model” and wondered whether we had ever distributed a description of it. In response, we described ABC’s culture instead. Year after year, it is what drives our success. Some aspects of ABC’s culture are not unique. We have top-notch staff and board; use the best science available; are unequivocally ethical; and follow excellent business practices. But other aspects of ABC stand out. With every project, we: • Get results that exceed expectations. Like the hummingbird in our logo, we are fearless, nimble, and fast-moving in achieving change for birds now. • Focus rigorously on our mission. For example, it is not within the scope of our mission to address the basic causes of climate change. But we plant millions of trees to contribute to bird habitat—helping the fight against climate change in the process. • Make no small plans. Small plans get small results. Our vision encompasses the conservation of all bird species in the Western Hemisphere. • Take pride in having low overhead and high output. ABC consistently receives Charity Navigator’s highest rating. • Make partnerships fundamental to almost everything we do. -

Ludlow Griscom

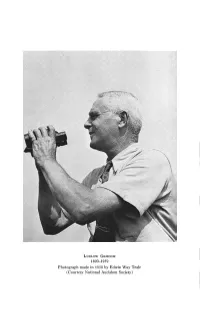

LUl)LOW GRxsco•r 1890-1959 Photograph made in 1950 by Edwin Way Teale (Courtesy National Audubon Society) IN MEMORIAM: LUDLOW GRISCOM ROGER T. PETERSON T•osE of us who might be called seniorornithologists recognize that Ludlow Griscomsymbolized an era, the rise of the competentbird- watcher.It washe, perhapsmore than anyoneelse, who bridgedthe gap betweenthe collectorof the old schooland the modernfield ornithologist with the binocular.He demonstratedthat practicallyall birdshave their field marksand that it is seldomnecessary for a trainedman to shoot a bird to know,at the specificlevel, precisely what it is. Like so many brilliant field birders, Ludlow Griscomwas born and raisedin New York City. He was born on June 17, 1890. His parents were ClementActon and GenevieveSprigg Griscom, who took him almost every summer on motoring trips through Europe. Growing up in an internationalatmosphere (his grandfatherwas a general,an uncle was an admiral, and anotheruncle an ambassador),he becamea linguist at an early age. He was taught by private tutors until he was 11 and then attendedthe SymesSchool where at the age of 15 he passedthe entrance examinationsfor Harvard. Being too young, he was kept at home for two more years where he devotedmost of his time to music and languages.In fact, he becameso skilled at the keyboard that he entertainedthe thought of becominga concertpianist. However, his interestin birds,sparked at the age of 6, had by now gainedascendancy over the piano,much to the disapprovalof his parents,who felt he was wasting his time. At the age of 17 he enrolledat ColumbiaUniversity where he took a pre-law course.Because of his family backgroundand fabulouslinguistic ability (he learnedto speak5 languagesfluently, could read 10 easily, and could translateup to 18 with a little help), his parentsinsisted that he preparefor the foreignservice, but he would have none of this. -

Summer 2017 No

Goodbye, old friends SUMMER 2017 NO. 400 Chan Robbins dies at age 98 INSIDE THIS ISSUE It is with sadness we pay homage to the memory of Chan Robbins, who passed Goodbye, old friends ..............1, 8 away on March 20. Revered as a father Welcome New Members ............1 of modern ornithology and an inspiration President’s Corner to all birders, he dedicated his life to the Moving Bird Collection .................2 study of avian life. He worked primarily Conservation Corner as an ornithologist at Patuxent Research Conservation Actions Refuge in Laurel, MD. (See Insert) ...................................2 Among his many achievements, Chan My Big Year, continued ......3, 8, 9 documented the damage wrought by the Bird Bits 2017 pesticide DDT. His data were used by BBC Summer Picnic .....................4 Rachel Carson in researching her 1962 manifesto, “Silent Spring.” He was Claire’s Scholarship Award ...........4 a champion of citizen science, founding the annual American Breeding Bird Audubon Plants for Birds Database ......................................4 Survey in 1965 as well as publishing his “A Guide to Field Identification: Gone Missing- Baltimore ..............5 Birds of North America” the same year. He was senior editor of the “Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia.” And, of Birds and Buildings ................6, 7 course, we all remember that early in his career he banded “Wisdom,” the Catalytic Converter For Laysan albatross who is still laying eggs in the Pacific Island of Midway 65 Bird -

Appendix C Remnant Prairies, Grasslands, and Birds

SOUTH DAKOTA PUC FACILITY PERMIT APPLICATION Appendix C Remnant Prairies, Grasslands, and Birds BROOKINGS COUNTY TO HAMPTON PAGE C-1 FALL 2010 SOUTH DAKOTA PUC FACILITY PERMIT APPLICATION This page intentionally left blank. FALL 2010 PAGE C-2 BROOKINGS COUNTY TO HAMPTON SOUTH DAKOTA PUC FACILITY PERMIT APPLICATION BROOKINGS COUNTY TO HAMPTON PAGE C-3 FALL 2010 SOUTH DAKOTA PUC FACILITY PERMIT APPLICATION FALL 2010 PAGE C-4 BROOKINGS COUNTY TO HAMPTON SOUTH DAKOTA PUC FACILITY PERMIT APPLICATION North American Breeding Bird Survey The U.S. Geological Survey’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center website provides the following information on the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS): What is the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS)? The BBS is a long-term, large-scale, international avian monitoring program initiated in 1966 to track the status and trends of North American bird populations. The USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center and the Canadian Wildlife Service, National Wildlife Research Center jointly coordinate the BBS program. Why was the BBS created? In the mid-twentieth century, the success of DDT as a pesticide ushered in a new era of synthetic chemical pest control. As pesticide use grew, concerns, as epitomized by Rachel Carson in Silent Spring, regarding their effects on wildlife began to surface. Local studies had attributed some bird kills to pesticides, but it was unclear how, or if, bird populations were being affected at regional or national levels. Responding to this concern, Chandler Robbins and colleagues at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center developed the North American Breeding Bird Survey to monitor bird populations over large geographic areas.