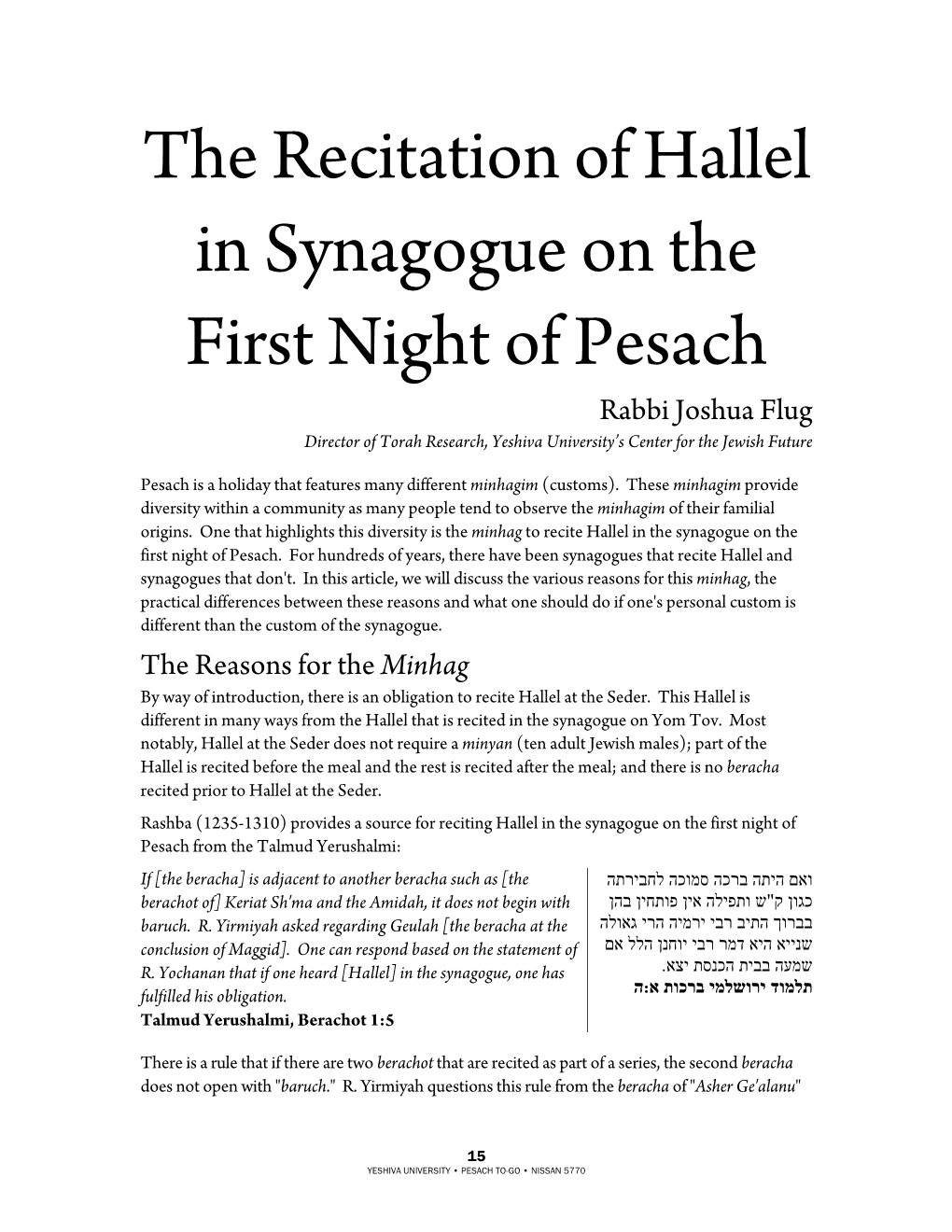

The Recitation of Hallel in Synagogue on the First Night of Pesach Rabbi Joshua Flug Director of Torah Research, Yeshiva University’S Center for the Jewish Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

A Synagogue for All Families: Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues

A Synagogue for All Families Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues Introduction Across North America, Conservative kehillot (synagogues) create programs, policies, and welcoming statements to be inclusive of interfaith families and to model what it means for 21st century synagogues to serve 21 century families. While much work remains, many professionals and lay leaders in Conservative synagogues are leading the charge to ensure that their community reflects the prophet Isaiah’s vision that God’s house “shall be a house of prayer for all people” (56:7). In order to share these congregational exemplars with other leaders who want to raise the bar for inclusion of interfaith families in Conservative Judaism, the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) and InterfaithFamily (IFF) collaborated to create this Interfaith Inclusion Resource for Conservative Synagogues. This is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point. This document highlights 10 examples where Conservative synagogues of varying sizes and locations model inclusivity in marketing, governance, pastoral counseling and other key areas of congregational life. Our hope is that all congregations will be inspired to think as creatively as possible to embrace congregants where they are, and encourage meaningful engagement in the synagogue and the Jewish community. We are optimistic that this may help some synagogues that have not yet begun the essential work of the inclusion of interfaith families to find a starting point that works for them. Different synagogues may be in different places along the spectrum of welcoming and inclusion. Likewise, the examples presented here reflect a spectrum, from beginning steps to deeper levels of commitment, and may evolve as synagogues continue to engage their congregants in interfaith families. -

Yamim Noraim Flyer 12-Pg 5771

Days of Awe ………….. 5771 Rabbi Linda Holtzman • Rabbi Yael Levy Dina Schlossberg, President • Rabbit Brian Walt, Rabbi Emeritus Gabrielle Kaplan Mayer, Coordinator of Spiritual Life for Children & Youth Rivka Jarosh, Education Director 4101 Freeland Avenue • Philadelphia, PA 19128 Phone: 215-508-0226 • Fax: 215-508-0932 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.mishkan.org DAYS OF AWE 5771 Shalom, Welcome to a year of opportunity at Mishkan Shalom! Our first of many opportunities will be that of starting the year together at services for the Yamim Noraim. It is a pleasure to begin the year as a community, joining old friends and new, praying and learning together. This year, Rabbi Yael Levy will not be with us at the services for the Yamim Noraim. We will miss Rabbi Yael, and hope that her sabbatical time is fulfilling and energizing and that we will learn much from her when she returns to Mishkan Shalom in November. Our services will feel different this year, but the depth and talent of our many members who will participate will add real beauty to them. I am thrilled that joining us to lead the davening will be Sue Hoffman, Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, Cindy Shapiro, Karen Escovitz (Otter), Elliott batTzedek, Wendy Galson, Susan Windle, Andy Stone, Bill Grey, Dan Wolk, several of our teens and many other Mishkan members. As we look ahead to the new year, we pray that 5771 will be filled with abundant blessings for us and for the world. I look forward to celebrating with you. L’shalom, Rabbi Linda Holtzman SECTION 1: LOCATION , VOLUNTEER FORM , FEES AND SERVICE INFORMATION A: WE HAVE • Morning services on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and all services on Yom Kippur will be held at the Haverford School . -

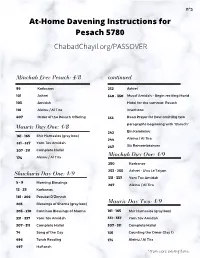

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Antisemitism in the United States Report of an Expert Consultation

Antisemitism in the United States Report of an Expert Consultation Organized by AJC’s Jacob Blaustein Institute for the Advancement of Human Rights in Cooperation with UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Dr. Ahmed Shaheed 10-11 April 2019, New York City Introduction On March 5, 2019, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, announced that he was preparing a thematic report on global antisemitism to be presented to the UN General Assembly in New York in the fall of 2019. The Special Rapporteur requested that the Jacob Blaustein Institute for the Advancement of Human Rights (JBI) organize a consultation that would provide him with information about antisemitism in the United States as he carried out his broader research. In response, JBI organized a two-day expert consultation on Wednesday, April 10 and Thursday, April 11, 2019 at AJC’s Headquarters in New York. Participants discussed how antisemitism is manifested in the U.S., statistics and trends concerning antisemitic hate crimes, and government and civil society responses to the problem. This event followed an earlier consultation in Geneva, Switzerland convened by JBI for Dr. Shaheed in June 2018 on global efforts to monitor and combat antisemitism and engaging the United Nations human rights system to address this problem.1 I. Event on April 10, 2019: Antisemitism in the United States: An Overview On April 10, several distinguished historians and experts offered their perspectives on antisemitism in the United States. In addition to the Special Rapporteur, Professor Deborah Lipstadt (Emory University), Professor Jonathan Sarna (Brandeis University), Professor Rebecca Kobrin (Columbia University), Rabbi David Saperstein (former U.S. -

Halachic Minyan”

Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shvat 5768 Intoduction 3 Minyan 8 Weekdays 8 Rosh Chodesh 9 Shabbat 10 The Three Major Festivals Pesach 12 Shavuot 14 Sukkot 15 Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah 16 Elul and the High Holy Days Selichot 17 High Holy Days 17 Rosh Hashanah 18 Yom Kippur 20 Days of Thanksgiving Hannukah 23 Arba Parshiot 23 Purim 23 Yom Ha’atzmaut 24 Yom Yerushalayim 24 Tisha B’Av and Other Fast Days 25 © Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal [email protected] [email protected] Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” 2 Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shevat 5768 “It is a positive commandment to pray every day, as it is said, You shall serve the Lord your God (Ex. 23:25). Tradition teaches that this “service” is prayer. It is written, serving Him with all you heart and soul (Deut. 2:13), about which the Sages said, “What is service of the heart? Prayer.” The number of prayers is not fixed in the Torah, nor is their format, and neither the Torah prescribes a fixed time for prayer. Women and slaves are therefore obligated to pray, since it is a positive commandment without a fixed time. Rather, this commandment obligates each person to pray, supplicate, and praise the Holy One, blessed be He, to the best of his ability every day; to then request and plead for what he needs; and after that praise and thank God for all the He has showered on him.1” According to Maimonides, both men and women are obligated in the Mitsva of prayer. -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018 Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 CONTENTS NOTES ....................................................................................................1 DATES OF FESTIVALS .............................................................................2 CALENDAR OF TORAH AND HAFTARAH READINGS 5776-5778 ............3 GLOSSARY ........................................................................................... 29 PERSONAL NOTES ............................................................................... 31 Published by: The Movement for Reform Judaism Sternberg Centre for Judaism 80 East End Road London N3 2SY [email protected] www.reformjudaism.org.uk Copyright © 2015 Movement for Reform Judaism (Version 2) Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the MRJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. -

In Response to the Tree of Life Synagogue Mass Shooting October 27, 2018

In Response to the Tree of Life Synagogue Mass Shooting October 27, 2018 Dear Colleagues, Today there was a mass shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As we reflect on the news of this horrific tragedy, we also are faced with questions about the roles and responsibilities of educators and educational leaders in addressing the growing tide of hatred and discrimination across our nation. I wanted to share the following resources on how to confront antisemitism. The word antisemitism means prejudice against or hatred of Jews. "I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented." (Elie Wiesel's Acceptance Speech, on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, December 10, 1986) https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1986/wiesel-acceptance_en.html Addressing Anti-Semitism through Education (2018 Report) http://www.erinnern.at/bundeslaender/oesterreich/e_bibliothek/antisemitismus-1/neues- handbuch-von-odihr-und-der-unesco-zu-bildungsarbeit-gegen-antisemitismus USHMM Antisemitism https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/antisemitism Confront Antisemitism https://www.ushmm.org/confront-antisemitism Antisemitism Today https://www.ushmm.org/confront-antisemitism/antisemitism-the-longest- hatred/film/antisemitism-today Educators play a powerful role in society, and the USHMM program Oath and Opposition: -

Sukkot Schedule *All Zmanim Reflect Times in Manhattan

Sukkot Schedule *All Zmanim reflect times in Manhattan Friday, October 2 Erev Sukkot Shacharit 7:30am Candle Lighting 6:17pm Include Shel Shabbat v’Shel Yom Tov, and Shehecheyanu Minchah, Kabbalat Shabbat and Maariv 6:25pm An abridged Kabbalat Shabbat begins with Mizmor Shir Le-Yom ha-Shabbat Omit Ba-Meh Madlikin Kiddush for Shabbat and Yom Tov can be recited after 7:17pm in the Sukkah Recite Leyshev Ba-Sukkah and then Shehecheyanu Ushpizin can be recited every night Shabbat, October 3 Yom Tov, Day 1 Shacharit 9:30am No Lulav and Etrog on Shabbat Full Hallel Torah Reading and Haftarah Vayikra 22:26-23:44, Bemidbar 29:12-16, Zechariah 14:1-21 Yah Eli, Musaf for Yom Tov with Shabbat inclusions Hoshanot for Shabbat (Ohm Netzurah) Hoshanot can be recited at home standing in place Seudah Shlishit in the Sukkah before 5:21pm Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Candle Lighting and all preparations for 2nd day Yom Tov not before 7:15pm Kiddush for Yom Tov with Havdalah inclusions in the Sukkah Recite Shehecheyanu and then Leyshev Ba-Sukkah Sunday, October 4 Yom Tov, Day 2 Shacharit 9:30am Lulav and Etrog with Shehecheyanu One cannot wear gloves while performing this mitzvah Full Hallel Torah Reading and Haftarah Vayikra 22:26-23:44, Bemidbar 29:12-16, Melachim I 8:2-21 Yah Eli, Musaf for Yom Tov 1 Hoshanot (Lema’an Amitach) Mincha/Maariv 6:25pm Havdalah in the Sukkah (no Leyshev) 7:14pm Monday through Thursday, October 5-8 Shacharit 7:15am Lulav and Etrog Full Hallel Torah Reading M: Bemidbar 29:17-25, T: Bemidbar 29:20-28, W: -

Yom Hazikaron and Yom Ha'atzmaut – Israel's

YOM HAZIKARON AND YOM HA’ATZMAUT – ISRAEL’S MEMORIAL AND INDEPENDENCE DAYS ABOUT THE DAYS Yom HaZikaron , the day preceding Israel’s Independence Day, was declared by the Israeli Knesset to be Memorial Day for those who lost their lives in the struggles that led to the establishment of the State of Israel and for all military personnel who were killed as members of Israel’s armed forces. Joining these two days together conveys a simple message: Jews all around the world owe the independence and the very existence of the Jewish state to those who sacrificed their lives for it. Yom HaZikaron is different in character and mood from our American Memorial Day. In Israel, for 24 hours, all places of public entertainment are closed. The siren wails twice for two minutes throughout the country, first at 8:00 am to usher in the day, and again at 11:00 am before the public recitation of prayers in the military cemeteries. At the sound of the siren, all traffic and daily activities cease; the entire nation is still. Families are gathered in cemeteries and radio stations broadcast programs devoted to the lives of fallen soldiers. The list grows longer every year as Israel continues to labor for its very survival. Flags in Israel are flown at half mast, and the Yizkor (remembrance) prayer for Israel’s fallen soldiers is recited. May God remember His sons and daughters who exposed themselves to mortal danger in those days of struggle prior to the establishment of the State of Israel and (may He remember) the soldiers of the Israeli Defense Forces who fell in the wars of Israel. -

Halachic Minyan”

Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shvat 5768 Intoduction 3 Minyan 8 Weekdays 8 Rosh Chodesh 9 Shabbat 10 The Three Major Festivals Pesach 12 Shavuot 14 Sukkot 15 Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah 16 Elul and the High Holy Days Selichot 17 High Holy Days 17 Rosh Hashanah 18 Yom Kippur 20 Days of Thanksgiving Hannukah 23 Arba Parshiot 23 Purim 23 Yom Ha’atzmaut 24 Yom Yerushalayim 24 Tisha B’Av and Other Fast Days 25 © Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal [email protected] [email protected] Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” 2 Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shevat 5768 “It is a positive commandment to pray every day, as it is said, You shall serve the Lord your God (Ex. 23:25). Tradition teaches that this “service” is prayer. It is written, serving Him with all you heart and soul (Deut. 2:13), about which the Sages said, “What is service of the heart? Prayer.” The number of prayers is not fixed in the Torah, nor is their format, and neither the Torah prescribes a fixed time for prayer. Women and slaves are therefore obligated to pray, since it is a positive commandment without a fixed time. Rather, this commandment obligates each person to pray, supplicate, and praise the Holy One, blessed be He, to the best of his ability every day; to then request and plead for what he needs; and after that praise and thank God for all the He has showered on him.1” According to Maimonides, both men and women are obligated in the Mitsva of prayer. -

The Uses of the Synagogue

The uses of the synagogue Bet k’nesset (house of meeting) The word ‘synagogue’ refers to a Jewish place of worship; many Jews refer to it as the bet k’nesset (house of meeting). The synagogue has an important role to play in the wider Jewish community. The name ‘bet k’nesset’ reflects the fact that as well as a place of prayer and worship, the synagogue plays a valuable role as that of a social centre, where various activities take place just as at the original Temple in Jerusalem. Modern synagogues are usually built with meeting rooms or classrooms incorporated into the building. There will sometimes be a hall for community use, which acts as a venue for a variety of events such as bar mitzvah and wedding celebrations. The synagogue therefore acts as a hub for all ages, holding youth club meetings, hosting lectures, and providing a meeting place for senior citizens. ‘Bet midrash’ (house of study) The name ‘bet midrash’ (house of study) and ‘shul’ (school) refers to the synagogue as a place for study and underlines the fact that education is very important in Jewish life. The Torah says: ‘And these words which I command you today shall be in your heart. You shall teach them diligently to your children …’ (Deuteronomy 6:6-7). For many Jewish children who attend secular schools, there is no opportunity to study Hebrew as part of the mainstream curriculum. For this reason, Jewish children are able to attend Hebrew classes that are held at the synagogue. However, education does not stop with children.