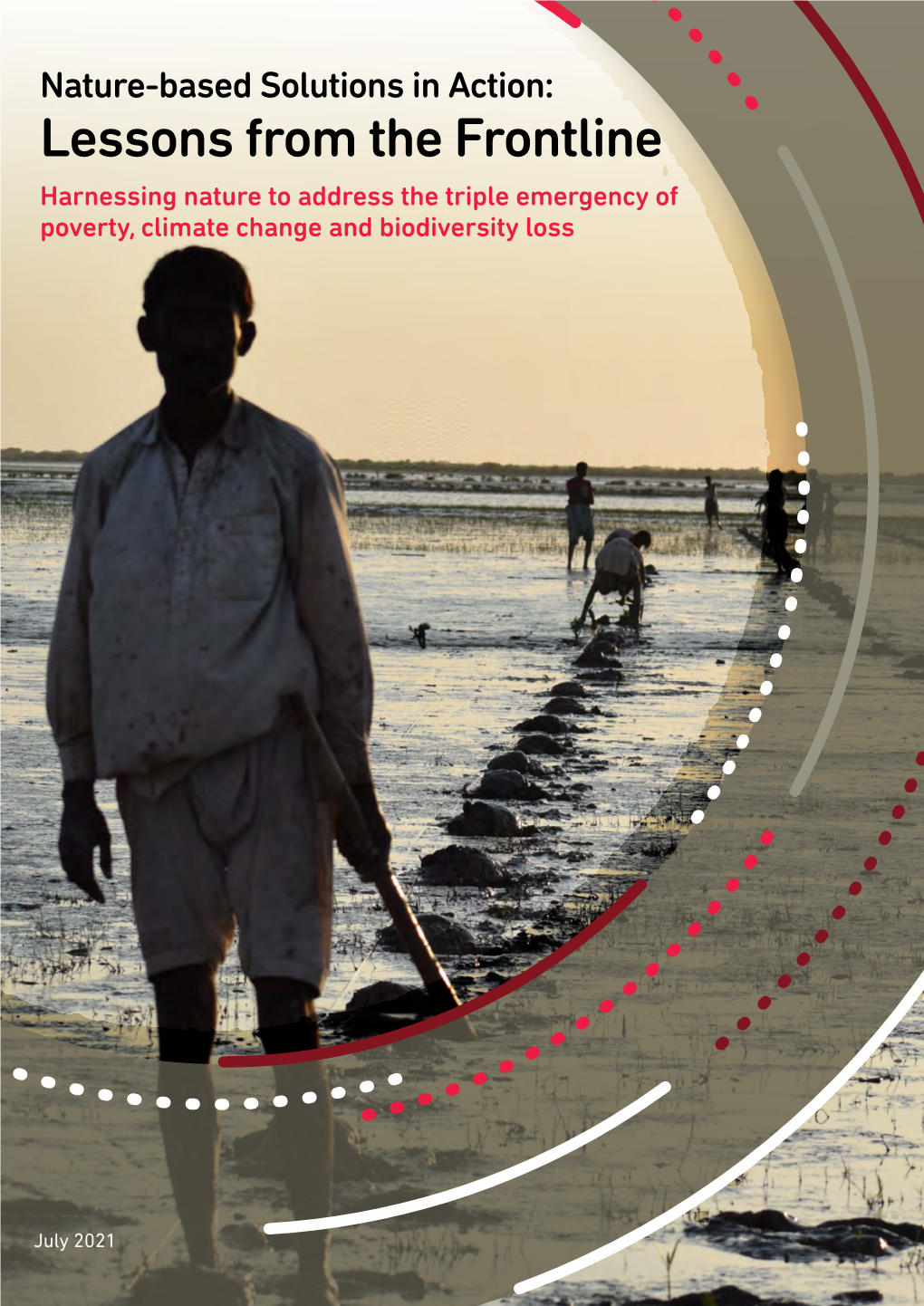

Nature-Based Solutions in Action: Lessons from the Frontline Harnessing Nature to Address the Triple Emergency of Poverty, Climate Change and Biodiversity Loss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carpena, Pietro, TREE AID Supporting the Development Of

Carpena, Pietro, TREE AID Supporting the development of locally controlled small-scale enterprises based on non-timber forest products in Burkina Faso: TREE AID’s experience Authors: Pietro Carpena - TREE AID; Désiré Ouedraogo - TREE AID; Alexis Sompougdou - TREE AID; Barthélémy Kaboret - TREE AID In the fight against poverty the use of forest products are often quoted as having significant potential to improve the livelihoods of rural people living within or close to forest areas. TREE AID works in Africa’s drylands to unlock the potential of trees to tackle poverty and improve the environment. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are an important part of traditional livelihoods in the drylands of West Africa. Communities generally have free access to communal forest resources, and NTFPs are already an important alternative source of income for rural households – especially women. However, marketing forest products to reduce poverty can be hindered by several factors including poor management and business skills, lack of investment, poor market access and information and dwindling natural resource base. Over the last decade, through its programmes, TREE AID has guided the self-organisation of hundreds of village interest groups in Burkina Faso, Mali and Ghana to develop and manage small businesses, also known as village tree enterprise (VTE) groups, based on NTFPs. With support from the Market Analysis and Development (MA&D) approach developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), TREE AID has provided the crucial structures that are necessary to achieve this empowerment. The support to VTEs groups covers all aspects of the NTFP value chain by facilitating market linkages and introducing private sector approaches to marketing and customer retention to ensure that expanded agricultural enterprise is achieved. -

6.2 Pro-Poor Forest Governance in Burkina Faso and Tanzania

ETFRN NEws 53: ApRil 2012 6.2 pro-poor forest governance in Burkina Faso and Tanzania JuLIA PAuLSON, GEMMA Salt, TONY HILL, LuDOVIC Conditamde, DéSIRé OuEDRAOGO and JOANNA WAIN introduction This paper discusses initiatives in pro-poor forest governance in two african countries: Burkina Faso and Tanzania. The term “pro-poor forest governance” means equitable, decentralized decision-making that recognizes the rights and responsibilities of the local forest users and communities who depend on forests for their livelihoods. This aligns with the Forest Governance learning Group (FGlG)1 definition of good forest governance, which “reflects the decisions and actions that remove barriers and install policy and institution- successes in pro-poor al systems which spread local forestry success.”2 governance and in key features include participation, accountabil- ity, equity, fairness, transparency, local control communiTy decisions and management. abouT foresT resources need To be connecTed wiTh oTher africa is the only continent where rates of deforestation continue to worsen,3 and forests processes wiThin The foresT secTor. are tightly linked to the livelihoods of poor rural african households.4 pro-poor forest governance — which puts decision-making power in the hands of poor forest users — offers the potential to both secure livelihoods and protect forests. The following factors have enabled the successes in Burkina Faso and Tanzania: • enabling policy frameworks; • working in multi-level collaborative networks; • connecting local enterprise and forest management; • a learning-by-doing approach; and • facilitating learning exchanges. Burkina Faso and Tanzania This article draws on evidence from two very different countries. Burkina Faso, in West africa, has a total forest cover of approximately 26% or 7.1 million hectares (ha), 67,000 ha of which is planted forest. -

Consolidated 2018 Detailed Implementation Plan (DIP) for the Drylands Development Programme (Drydev)

Consolidated 2018 Detailed Implementation Plan (DIP) for the Drylands Development Programme (DryDev) A Farmer Led Programme to Enhance Water Management, Food Security, and Rural Economic Development in the Drylands of Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Ethiopia, and Kenya ***2018*** Contents ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2. ICRAF Coordination Detailed Implementation Plan, 2018 ........................................................................... 7 2.1 Summary of Lessons Learned from 2017 ......................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Key Priorities for 2018 .............................................................................................................................................. 7 2.2.1 Staffing Changes .................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.2.2 Main Coordination Focus for 2018 .............................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Description of Activities by Coordination Support Area (CSA) for 2018 ............................................. 8 -

For Agriculture Development

A4DVol2-4CoverWeb 21/12/2009 9:39 pm Page 1 Agriculture for Development Melville Memorial Lecture Caribbean agricultural research Ethiopia forest management No. 8 Winter 2009 A4DVol2-4CoverWeb 21/12/2009 9:39 pm Page 2 A4DVol2-4Textweb 21/12/2009 9:41 pm Page 1 The TAA is a professional association of individuals and Contents corporate bodies concerned with the role of agriculture for 2 Editorial | COP15: will it succeed? development throughout the Articles world. TAA brings together individuals and organisations 3 Melville Memorial Lecture | Where theory and practice meet: Innovation, from both developed and less- communication and extension among smallholder farmers | Chris Garforth developed countries to enable 8 Agricultural research in the Caribbean: an outline from Victorian times until today them to contribute to | Bruce Laukner international policies and actions aimed at reducing poverty and 13 Agroforestry and Conservation Agriculture: complementary practices for improving livelihoods. Its sustainable development | Brian Sims, Theordor Freidrich, Amir Kassam and Josef mission is to encourage the Kienzle efficient and sustainable use of 19 Conservation agriculture: south-south technology transfer from Brazil to East local resources and technologies, to arrest and reverse the Africa | Brian G. Sims degradation of the natural South-West Group resources base on which 21 Historical background to forest management in Ethiopia | Stephen Sandford agriculture depends and, by 26 Doing development: why small can be beautiful, some perspectives from a Kitchen raising the productivity of both agriculture and related Table Trust | John Rosewell and Tigist Grieve enterprises, to increase family Newsflash incomes and commercial 30 Red Button Design | Amanda Jones investment in the rural sector. -

After Planting 5200 Trees in the Sahel

Paris, France – May 2021 Press release AFTER PLANTING 5,200 TREES IN THE SAHEL SINCE 2020 WITH NGO TREE AID, ALLAND & ROBERT CREATES ITS COMPANY FOUNDATION TO HELP WITH THE PREVENTION OF DESERTIFICATION IN AFRICA By 2030, the Great Green Wall will have revived 100 million hectares of dryland to fight the advancing Sahara desert. How? By growing trees on an 8,000 km strip that stretches over twenty countries in the sub-Saharan zone, from Senegal to Djibouti. Partner of this initiative with the NGO Tree Aid, Alland & Robert reinforces its historic commitment to African communities and creates its company foundation. In the Sahel, the consequences of climate change are significant. The climate crisis worsens the poverty of local populations, destroys food crops and endangers the future of young generations. One of the reasons for this disaster: the advance of the Sahara, accelerating from year to year. The Great Green Wall initiative was born in 2007 to counter this phenomenon. In this context, Alland & Robert announces the creation of its Company Foundation. Its statutes were filed on May 11th, 2021 and its mission is to manage Alland & Robert’s commitments to the environment and the Sahelian communities related to the acacia gum harvest. Alland & Robert is one of the major manufacturers of acacia gum worldwide. One of the foundation’s main projects will be to strengthen the partnership between Alland & Robert and Tree Aid, a UK-based NGO (Non-Governmental Organization) expert of African drylands and reforestation, and a participant in the Great Green Wall project. In 2020, the first year of this Committed to the African communities since the creation partnership, Alland & Robert helped plant 3,600 trees which of the company in 1884, Alland & Robert decided to create corresponds to approximately 36 hectares of restored land. -

Reshaping the Terrain Forest and Landscape Restoration in Burkina Faso 1

Reshaping the terrain Forest and landscape restoration in Burkina Faso 1 GLF Factsheet | August 2018 Reshaping the terrain Forest and landscape restoration in Burkina Faso Mathurin Zida* Construction of half-moon anti erosion micro basins 2, Djibo area, Burkina Faso Introduction Land degradation is a key issue in Burkina Faso’s sustainable development equation. Recent analyses show that degradation occurs at a rate of about 470,000 ha per year, affecting 51,600 km2, 19 percent, of the national territory (MEEVCC 2018). The annual price tag is estimated to be equal to 26 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (Global Mechanism of the UNCCD 2018). Huge efforts have been undertaken by numerous stakeholders to tackle the problem. Currently, Burkina Faso is taking advantage of the Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) program, with which it aligned in 2016, by setting its national voluntary goals and identifying measures to achieve them by 2030 (SPONG and CARI 2017; MEEVCC 2018; UNCCD 2018). Reforestation efforts Examples of on-going restoration-related projects include: Neer-Tamba project in North, Center North and An analysis of degradation trends conducted East regions; ProSol project in Haut-Bassin region; EBA- between 2002 and 2013 revealed that degrada- FEM project in Boucle du Mouhoun and Sahel regions; tion hot-spots exist throughout the country’s three Forest Investment Program (FIP) in Boucle du Mouhoun, eco-regions – the Sahelian, Sudano-Sahelian and Center West, South West and East regions; Great Green Sudanese zones – with varying levels of severity Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative (GGWSSI) in (MEEVCC 2018). -

The Contribution of Tree Crop Products to Smallholder Households

FAO COMMODITY AND TRADE POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER No. 49 THE CONTRIBUTION OF TREE CROP PRODUCTS TO SMALLHOLDER HOUSEHOLDS A CASE STUDY OF BAOBAB, SHEA, AND NÉRÉ IN BURKINA FASO The contribution of tree crop products to smallholder households A case study of baobab, shea, and néré in Burkina Faso by Camilla Audia, SOAS, University of London Bartélémy Kaboret, TREE AID Rebecca Kent, Canterbury Christ Church University Tony Hill, TREE AID Nigel Poole, SOAS, University of London Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2015 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

Forest Connect Country Report Burkina Faso

___________________________________ Forest Connect Country Report, Burkina Faso FOREST CONNECT COUNTRY REPORT BURKINA FASO Prepared by Elvis Paul Tangem TREE AID October 2011 1 ___________________________________ Forest Connect Country Report, Burkina Faso List of Acronyms ANSAB Asia Network for Sustainable Agriculture and Bio-resources APFNL Agence de Promotion des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux ARSA Amélioration des revenues et de la sécurité alimentaire BDS Business Development Service CIFOR Centre for International Forestry Research CSO Civil Society Organizations FAO Food and Agriculture Organization (of the United Nations) FC Forest Connect GDP Gross Domestic Product GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (German International Development Support) IIED International Institute for Environment and Development MA&D Market Analysis & Development Approach MECV Ministerè de L’Environnement et du Cadre de Vie MEDD Ministerè de L’Environnement et Developpement Durable (Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development) MFI Micro finance Institution NGO Non Governmental Organisation NTFP Non Timber Forest Product PAGED Projet d’Amélioration de la Gestion et de L’exploitation Durable des PFNLs PFNL Produit Forestière Non-Ligneux SMFE Small and Medium Forest Enterprises TCP Technical Cooperation Project VTE Village Tree Enterprise (programme) 2 ___________________________________ Forest Connect Country Report, Burkina Faso Forest Connect Country Report, Burkina Faso September 2007 to July 2011 1. Institutional History 1.1 Initial motivation and expectations In Burkina Faso, the contribution of the forestry sector to GDP (along with hunting and fishing) was estimated at 15% in 20071, but this is likely to be an underestimate since several activities linked to NTFPs are not considered2. SMFEs create added value through wood and non timber forest products and represent a promising niche to alleviate poverty and diversify livelihoods for rural populations, whilst conserving the natural resource base through sustainable forestry management. -

Inside This Issue

UPDATE 2020 ISSUE 15 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: NEW PROJECT AROUND NIGER'S PARK W INCREASING INCOMES THROUGH CASHEW FARMING A GUIDE TO HOW WE MONITOR OUR WORK TREES MEAN LIFE TREES MEAN LIFE TREES MEAN LIFE Dear supporters, There are lots of Highlights in this issue exciting projects underway this year. As TREE AID’s 4 Increasing Programme Funding incomes Officer I’m delighted through to be able to tell you that we have cashew recently secured funding for a new farming project in Niger’s W National Park. This is our second project in the park and is being made possible thanks to funding from The Swedish Postcode Foundation. The new project will expand our existing 6 Monitoring work in the park to a new area in and our around Dosso. You can find out more work for on page 8. Other highlights in this maximum edition are an introduction to how we impact monitor and assess the impact of our work, and an update on our innovative cashew farming project which is helping communities in Ghana to earn much needed income. None of these projects and the life changing impact they 8 New project have would be possible without our in Niger supporters, so thank you. National Park W Best wishes Becky Graham Programme Funding Officer Front cover image: Tree planting in Yendi, Ghana. Get the latest Photo: Rowan Griffiths – Daily Mirror news and insights about our work on Sign-up to receive TREE AID email updates for the latest news, our website insights and information on how to get more involved. -

Integrated Approach to Resilience Building: a Case of the Dry-Lands Development Programme (DRYDEV)

Integrated approach to resilience building: a case of the Dry-lands Development Programme (DRYDEV) A Farmer-led initiative to Enhance Water Management, Food Security, and Rural Economic Development in the Dry Lands of Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mali and Niger. Phosiso Sola, PhD East Africa Programme Coordinator-DRYDEV [email protected] and DryDev teams http://drydev.org/ 3rd Africa Drylands Weeks, Safari Court Hotel, Windhoek 9th August 2016 The programme • Five-year initiative (August 2013 to July 2018) funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) of the Netherlands and World Vision Australia (WVA). • The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) is the overall implementing agency working with a Consortium of 21 NGOs Country National Lead Implementing Partners Organization Burkina Faso Reseau Marp SNV; Tree Aid Ethiopia World Vision EOC/DICAC; REST Kenya World Vision SNV; CARITAS; ADRA Mali Sahel Eco OXFAM; AMEDD; AMEPPE Niger Care International OXFAM; World Vision; KARKARA; AREN; RAIL; CRESA Programme sites Country County/Region District/Subcounty/Commune Burkina Faso Sourou Kiembara Tougan Zondoma et Yatenga Oula; Bassi Tougo Yatenga Zogoré; Tangaye Bam Tikaré; Kongoussi Passoré Arbollé; Kirsi Sanguié Tenado; Réo; Khyon; Koudougou Ethiopia Oromia Boset; Gursum; arso Tigray Tseada Emba; Kilite Awlalo; Samre Kenya Kitui Mwingi Central; Kitui Rural Makueni Mbooni; Kibwezi East Machakos Yatta; Mwala Mali Sikasso Yorosso; Koutiala Segou Segou; Tominian Mopti Bankass; Bandiagara Niger Torodi Digbari Middle; Goroubi East; Goroubi west Dogon Kiria Dallol North; Dallol Middle; Dallol South Malbaza Maggia North; Maggia South –East; Maggia West Aguie Goulbin Kaba North –East; Goulbin Kaba South –East Droum SC Korama Damagaram North East; SC Korama Damagaram South East The programme Vision: Households residing in arid and semi arid areas have transitioned from subsistence farming and emergency aid to sustainable rural development • Through increasing food and water security, enhancing market access, and strengthening the local economy for different categories of farmers. -

When Trees Mean Life

WHEN TREES MEAN LIFE TREE AID Annual Review 2010/11 WE KNOW THAT TACKLING POVERTY AND PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT ARE INSEPARABLE. Poor people suffer disproportionately when their immediate environment is degraded. They are often forced to over exploit their natural resources simply to survive. This leads to greater poverty and increased vulnerability to the impact of climate change. The very existence of rural communities is then threatened by extreme weather events. This is why we unlock the potential of trees to reduce poverty and protect the environment. THIS IS WHY WE BELIEVE... TREES MEAN LIFE are cut down. TREE AID’s work FO R E V erY tree is ending this cycle for the P L A N ted I N A fri C A 28 communities with which it works. INTRODUCTION This year we continued to make our actions count where they matter most – using trees to improve the lives of African rural smallholders and their families. In 2010/11, this means we created opportunities for This year we started a TREE REVOLUTION hundreds of thousands more people to generate to see 1 million trees planted, protected and WHERE WE WORK a vital, year-round supply of FOOD, with tree producing within 2011 – so that even more lives can The Sahel means ‘the shore of the desert’ and produce such as dried fruits, nuts and leaves be transformed. Meeting this target is only possible is an area that was historically rich in flora and providing nutrition when other crops fail (page 3). if we can raise the funds to deliver it. -

Trustee Role Description – May 2021

Tree Aid Trustee role description – May 2021 A message from Shireen Chambers, Chair of Trustees Thank you very much for your interest in Tree Aid and I hope you will apply for the position of trustee. Tree Aid has built up a strong reputation internationally as a high performing organisation that is able to deliver on its promises. We are an innovative, knowledgeable and specialist charity focusing on the role of trees in tackling poverty and combatting the climate crisis in dryland Africa. The demand for our work is enormous. As Chair of Tree Aid, it is my great privilege to provide, with the other trustees, the leadership and guidance to support this work, focusing on its quality and long-term impact. Given the incredible need for our work, we continue to set ourselves the ambitious targets for expansion and will be developing our next organisational strategy this year. We are looking to build the influence and impact of our work by sharing our experience more widely. For this reason, we are looking for three new trustees to strengthen our Board that offer expertise in either international development, financial management and oversight, and advocacy and policy. As stated in the material, Tom Skirrow, the Chief Executive, is available for more information and if you then want to talk to me specifically about the roles and requirements, please let him know and I will be in touch. With best wishes and thanks again for considering serving this organisation, which does such important work in improving the prospects of poor people across dryland Africa.