Somalis in Leicester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development

Published by the British Broadcorrmn~Corporarion. 35 Marylebone High Sneer, London, W.1, and printed in England by Warerlow & Sons Limited, Dunsruble and London (No. 4894). BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development PUBLISHED TO MARK THE 4oTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BBC AUGUST 1962 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION SOUND RECORDING The Introduction of Magnetic Tape Recordiq Mobile Recording Eqcupment Fine-groove Discs Recording Statistics Reclaiming Used Magnetic Tape LOCAL BROADCASTING. STEREOPHONIC BROADCASTING EXTERNAL BROADCASTING TRANSMITTING STATIONS Early Experimental Transmissions The BBC Empire Service Aerial Development Expansion of the Daventry Station New Transmitters War-time Expansion World-wide Audiences The Need for External Broadcasting after the War Shortage of Short-wave Channels Post-war Aerial Improvements The Development of Short-wave Relay Stations Jamming Wavelmrh Plans and Frwencv Allocations ~ediumrwaveRelav ~tatik- Improvements in ~;ansmittingEquipment Propagation Conditions PROGRAMME AND STUDIO DEVELOPMENTS Pre-war Development War-time Expansion Programme Distribution Post-war Concentration Bush House Sw'tching and Control Room C0ntimn.t~Working Bush House Studios Recording and Reproducing Facilities Stag Economy Sound Transcription Service THE MONITORING SERVICE INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION CO-OPERATION IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH ENGINEERING RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING ELECTRICAL INTERFERENCE WAVEBANDS AND FREQUENCIES FOR SOUND BROADCASTING MAPS TRANSMITTING STATIONS AND STUDIOS: STATISTICS VHF SOUND RELAY STATIONS TRANSMITTING STATIONS : LISTS IMPORTANT DATES BBC ENGINEERING DIVISION MONOGRAPHS inside back cover THE BEGINNING OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED KINGDOM (UP TO 1939) Although nightly experimental transmissions from Chelmsford were carried out by W. T. Ditcham, of Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, as early as 1919, perhaps 15 June 1920 may be looked upon as the real beginning of British broadcasting. -

Report on Information and Communication for Development

Policy and Research Programme on Role of Media and Communication in Development Final Project Report April 2010 – March 2012 Grant Reference Number: AG4601 MIS Code: 732-620-029 Contact: James Deane, Head of Policy [email protected] BBC Media Action Bush House, PO Box 76, Strand, London WC2B 4PH Telephone +44 (0) 207 557 2462, Fax +44 (0)207 379 1622, E-mail: [email protected] www.bbcworldservicetrust.org 2 BBC Media Action Policy and Research Programme on the Role of Media and Communication in Democratic Development INTRODUCTION This is the final report of the Policy and Research Programme on the Role of Media and Communication Development. It provides a narrative overview of progress and impact between April 2010 and March 2012 of the DFID funded Policy and Research Programme on the Role of Media in Development, building on an earlier report submitted for activities carried out between April 2010 and March 2011. In 2006 the Department for International Development (DFID) allocated £2.5 million over five years for the establishment of a 'Policy and Research Programme on the Role of Media and Communication in Development' to be managed by BBC Media Action (formerly the BBC World Service Trust). The Programme ran from July 2006 through to March 2012, including a no-cost extension. A small additional contribution to the Programme from the Swedish International Development Agency was received over the period (approximately £300,000 over the period 2009- 2012). In November 2011, DFID reached agreement with the BBC World Service Trust (since January 2012, renamed as BBC Media Action) for a new Global Grant amounting to £90 million over five years. -

The Evaluation of the Leicester Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Strategy

The Evaluation of the Leicester Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Strategy Phase 2 Report Informed by the T.P.U. Deep Dive Findings Centre for Social Action January 2007 The Research Team Peer Evaluators Alexan Junior Castor Jordan Christian Jessica Hill Tina Lee Lianne Murray Mikyla Robins Sian Walker Khushbu Sheth Centre for Social Action Hannah Goodman Alison Skinner Jennie Fleming Elizabeth Barner Acknowledgements Thanks to: Practitioners who helped to arrange sessions with our peer researchers or parents Rebecca Knaggs Riverside Community College Michelle Corr New College Roz Folwell Crown Hills Community College Anna Parr Kingfisher Youth Club Louise McGuire Clubs for Young People Sam Merry New Parks Youth Centre Harsha Acharya Contact Project Vanice Pricketts Ajani Women and Girls Centre Naim Razak Leicester City PCT Kelly Imir New Parks STAR Tenant Support Team Laura Thompson Eyres Monsell STAR Tenant Support Team Young people who took part in the interviews Parents who took part in the interviews Practitioners who took part in the interviews, including some of the above and others Connexions PAs who helped us with recruitment Also: Teenage Pregnancy and Parenthood Partnership Board Mandy Jarvis Connexions Liz Northwood Connexions HR Kalpit Doshi The Jain Centre, Leicester Lynn Fox St Peters Health Centre Contents Page No. Acknowledgements Executive Summary 1 Methodology 7 Information from young people consulted at school and in the community 15 What Parents told us 30 What Practitioners told us 39 Perspectives from School Staff Consultation -

Barbara Avenue Humberstone, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE5 2AD

Barbara Avenue Humberstone, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE5 2AD Offers Over £320,000 Kings are delighted to present this 5 Bed extended Semi-Detached property in the popular Humberstone area. The property comprises of x2 Lounge, Modern Kitchen/Diner, 5 Bedrooms, Bathroom, x2 WC, Large Rear garden, Call Kings today on 0116 352 7012. Property Features room. Upstairs you have; the spacious landing leading to all rooms, including the insulated loft with a pull down ladder for access, bedroom two, bedroom four, the separate WC and . HIGHLY SOUGHT . OFF ROAD PARKING four piece family bathroom, bedroom three boasting fitted LOCATION wardrobes, the bay fronted bedroom one and last but not . Large Garden least is bedroom five. The rear garden boasts; a patio area, . Close to Amenities & . uPVC Double Glazing Schools lawned area and mature shrubbery around the edges, additionally at the rear you have a spacious stoned area and . GARAGE/UTILITY . Modern Fitted a double size shed, perfect for a keen gardener or for Kitchen/Diner . Please call Kings on storage. At the front you have off road parking for two cars, 0116 352 7012 . VERY WELL access to the garage as well as having ample on street PRESENTED parking. UNDERFLOOR Call Kings today on 0116 352 7012. FullHEATING Description Kings are delighted to present this 5 Bed extended Semi-Detached property in the popular Humberstone area. Located just off Scraptoft Lane which provides excellent transport links to and from Leicester City Centre. Close to Rowlatts Hill Primary School/Al-Aqsa Schools Trust/Thurnby Lodge Primary Academy. Close to local amenities located on Uppingham Road and close situated to Tesco Hamilton Superstore. -

![[LEICESTER.] EARL SHILTON. 354 [POST OFFICE Letters Arrive Through Lutlerworth at 9 A.M.; Dispatched I Boa1'd School, F](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0207/leicester-earl-shilton-354-post-office-letters-arrive-through-lutlerworth-at-9-a-m-dispatched-i-boa1d-school-f-210207.webp)

[LEICESTER.] EARL SHILTON. 354 [POST OFFICE Letters Arrive Through Lutlerworth at 9 A.M.; Dispatched I Boa1'd School, F

[LEICESTER.] EARL SHILTON. 354 [POST OFFICE Letters arrive through Lutlerworth at 9 a.m.; dispatched I BOa1'd School, F. Atkins, master at 5 p.m. The nearest money order office is at Lutter- CARRIERS.-Hipwell & Ward, to Leicester, saturday, worth . 7 a.m.; to Lutterworth, thursday Wood Rev. Lewis [vicar] Dunkley John, Crown ~ Thistle, & Oden Ogden, tailor shopkeeper Palmer Thomas, shoe maker COMMERCIAL. Hewitt William, carpenter ReynoldsAbsalom,Shoulderof J.lfution Bennett WiIliam, grocer Hobill John, miller Stretton Job, Crooked Billet Berridge William, farmer & grazier Hopkins William, farmer Sutton William, farmer Bird Charles, blacksmith J udkio J ames, farmer Swinfen J ames, farmer Bottrill J oho, colla.r & harness maker Masters Thomas, farmer Watts George, farmer & grazier Chambers John, farmer Moore Margaret (Mrs.), farmer Wright Joseph, shopkeeper EARL SHILTON is a township and ecclesiastical dis executors of Lady Noel Byron are lessees of the manor trict, 4 miles north-east from Hinckley, 1~ north-west from under the Duchy of Lancaster. The principal landowners Elmesthorpe station, 6 south-east from Market Bosworth, are the Corporation of Leicester, the trustees of the late 9 south-west from Leicester, and 100 from London, in the '1'. Atkins, esq., Joseph Pool, esq., Mr. J. Carr, and Mr_ Southern division of the county, Sparkenhoe hundred, Thomas Clarke. The soil is various; subsoil, gravel and Rinckley union and county court district, rural deanery of clay. The chief crops are wheat, barley, oats and roots. Sparkenhoe, archdeaconry of Leicester, and diocese of The acreage is 1,981; rateable value, £5,001; in 1871 the Peterborough, situated on the road from Hinckley to Lei population was 2,053. -

Annual Review 2008 Creative Partnerships in International Development Introduction

Annual Review 2008 Creative partnerships in international development introduction Mission The BBC World Service Trust uses media and Why media and communication to reduce poverty and promote human rights, thereby enabling people to build better lives for themselves. communication matters Vision We believe that independent and vibrant media are critical to the development of free and just societies. We live on a planet rich in resources We share the BBC’s ambition to strengthen the exchange and yet more than three billion people of accurate, impartial and reliable information to enable try to survive on less than $2.50 a day. people to make informed decisions. Our inspiration is a Many people in developing countries world in which individuals and civil society use media and are confronted with desperately diffi cult communications to become effective participants in their challenges: hunger, HIV and AIDS, own political, economic, social and cultural development. population growth, climate change, war, and the daily grind of poverty. The work is structured in three regions: Africa, Asia and Europe, Middle East and Central Asia. We are also When considering global inequality, there is involved in cross-cutting activities, including policy, public still the overarching perception among the affairs and business development that span all regions. general public and many people working for development agencies that the chief Our work focuses on two main areas, media development and importance of the media is to draw public development communications, and is delivered through four attention – especially in rich countries – to overarching themes: emergency response, governance the plight of people living in poverty. -

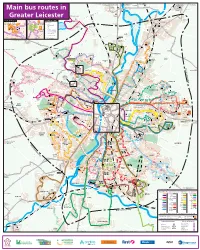

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Main Report Leicester and Blaby Town Centre Retail Study 2015

Leicester City Council and Blaby District Council Town Centre and Retail Study Final Report September 2015 Address: Quay West at MediaCityUK, Trafford Wharf Road, Trafford Park, Manchester, M17 1HH Tel: 0161 872 3223 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.wyg.com Document Control Project: Town Centre and Retail Study Client: Leicester City Council and Blaby District Council Job Number: A088154 T:\Job Files - Manchester\A088154 - Leicester Retail Study\Reports\Final\Leicester and Blaby Retail File Origin: Study_Final Report.doc WYG Planning and Environment creative minds safe hands Contents Page 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Current and Emerging Retail Trends ................................................................................................ 3 3.0 Planning Policy Context .................................................................................................................. 16 4.0 Original Market Research ................................................................................................................ 28 5.0 Health Check Assessments.............................................................................................................. 67 6.0 Population and Expenditure ............................................................................................................ 149 7.0 Retail Capacity in Leicester and Blaby Authority Areas ..................................................................... -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Bristol: a City Divided? Ethnic Minority Disadvantage in Education and Employment

Intelligence for a multi-ethnic Britain January 2017 Bristol: a city divided? Ethnic Minority disadvantage in Education and Employment Summary This Briefing draws on data from the 2001 and 2011 Figure 1. Population 2001 and 2011. Censuses and workshop discussions of academic researchers, community representatives and service providers, to identify 2011 patterns and drivers of ethnic inequalities in Bristol, and potential solutions. The main findings are: 2001 • Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage than in England and Wales as a whole in 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% education and employment and this is particularly so for White British Indian Black African Black African people. White Irish Pakistani Black Caribbean Gypsy or Irish Traveller Bangladeshi Other Black • There was a decrease in the proportion of young people White other Chinese Arab with no educational qualifications in Bristol, for all ethnic Mixed Other Asian Any other groups, between 2001 and 2011. • Black African young people are persistently disadvantaged Source: Census 2001 & 2011 in education compared to their White peers. • Addressing educational inequalities requires attention Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage to: the unrepresentativeness of the curriculum, lack of than the national average in education and employment, diversity in teaching staff and school leadership and poor as shown in Tables 1 and 2. In Education, ethnic minorities engagement with parents. in England and Wales on average have higher proportions • Bristol was ranked 55th for employment inequality with qualifications than White British people but this is between White British and ethnic minorities. not the case in Bristol, and inequality for the Black African • People from Black African (19%), Other (15%) and Black Caribbean (12.7%) groups had persistently high levels of Measuring Local Ethnic Inequalities unemployment. -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

De Zayas Guantanamo Lecture.Pdf

© Professor Alfred de Zayas, Geneva THE DOUGLAS McK. BROWN LECTURE, UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA1 VANCOUVER, 19 NOVEMBER 2003 THE STATUS OF GUANTÁNAMO BAY AND THE STATUS OF THE DETAINEES Table of Contents I. Introduction Guantánamo before the United States Supreme Court Law abhors a vacuum II. Status of Guantánamo Bay in public international law A. 1903 Lease agreement B. United States interpretation C. Cuban interpretation D. History of the lease: the Spanish-American war and the “Platt Amendment” E. Four possible scenarios i. Lease in perpetuity: positivist approach ii. condominium iii. void ab initio because of coercion iv. voidable today a) as an unequal treaty b) because of emergence of new peremptory norm c) because of implied right of denunciation d) because of fundamental change in circumstances e) because of material breach of the lease agreement F. Conclusion III. Status of the detainees in public international law A. Three Applicable Regimes 1. International Human Rights Law 2. International Humanitarian Law 3. Domestic law, United States Constitution 1 Available electronically on http://www.law.ubc.ca/events/2003/november/McK_Brown_Lecture.html; to be published in the Spring 2004 issue of the Law Review of the University of British Columbia. The lecture is also available on video from the Office of the Dean of the Law School of the University of British Columbia.([email protected]). The lecture was repeated on 28 November 2003 at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. 1 B. Conclusion IV. Options for peaceful settlement A. Advisory Opinion by International Court of Justice B. Procedure under the Third Geneva Red Cross Convention of 1949: Good offices of United Nations Secretary General C.