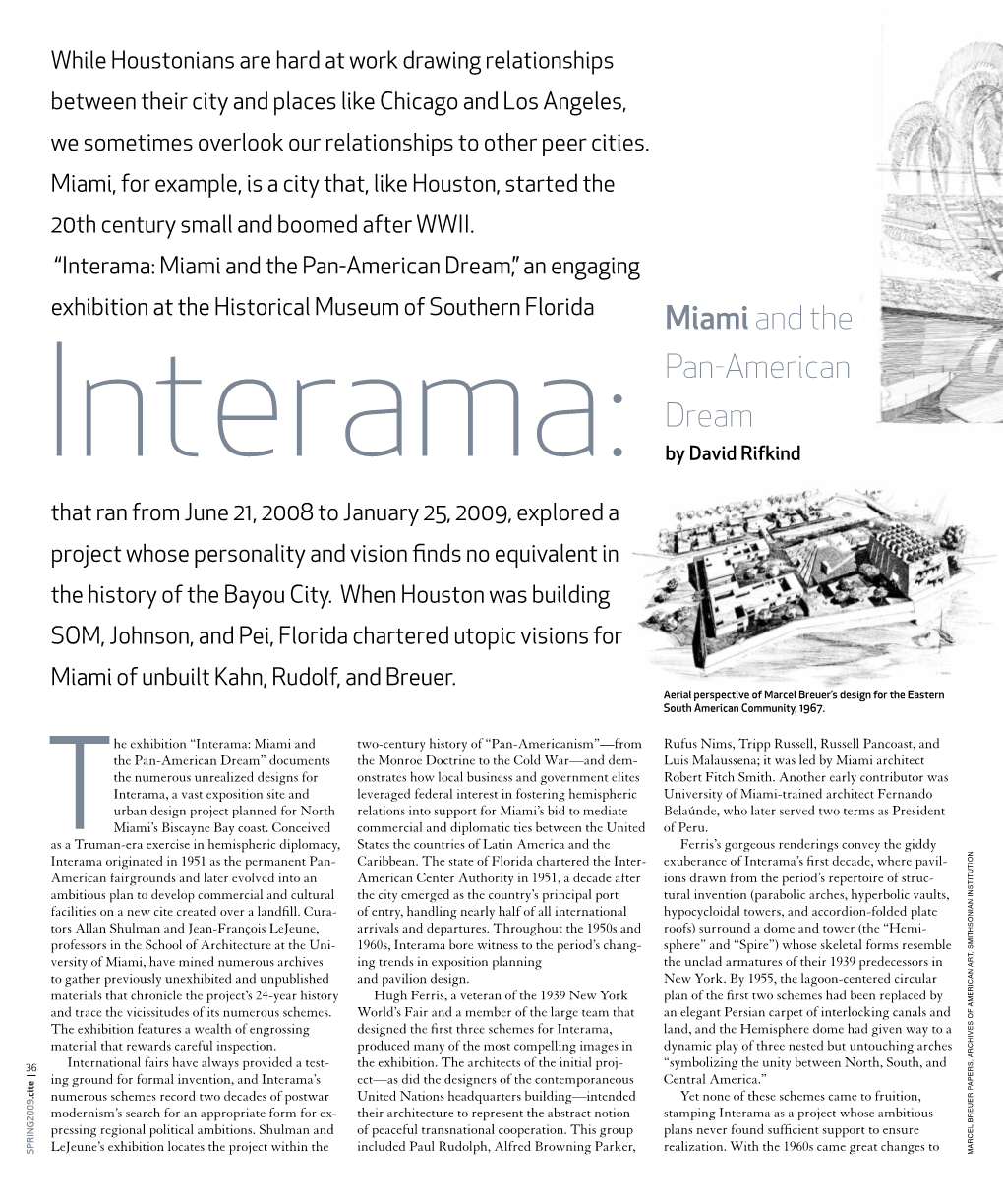

Interama: Miami and the Pan-American Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Contents

NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Contents 1 Message from the Chair The National Building Museum explores the world and the Executive Director we build for ourselves—from our homes, skyscrapers and public buildings to our parks, bridges and cities. 2 Exhibitions Through exhibitions, education programs and publications, the Museum seeks to educate the 12 Education public about American achievements in architecture, design, engineering, urban planning, and construction. 20 Museum Services The Museum is supported by contributions from 22 Development individuals, corporations, foundations, associations, and public agencies. The federal government oversees and maintains the Museum’s historic building. 24 Contributors 30 Financial Report 34 Volunteers and Staff cover / Looking Skyward in Atrium, Hyatt Regency Atlanta, Georgia, John Portman, 1967. Photograph by Michael Portman. Courtesy John Portman & Associates. From Up, Down, Across. NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 The 2003 Festival of the Building Arts drew the largest crowd for any single event in Museum history, with nearly 6,000 people coming to enjoy the free demonstrations “The National Building Museum is one of the and hands-on activities. (For more information on the festival, see most strikingly designed spaces in the District. page 16.) Photo by Liz Roll But it has a lot more to offer than nice sightlines. The Museum also offers hundreds of educational programs and lectures for all ages.” —Atlanta Business Chronicle, October 4, 2002 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR AND THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR responsibility they are taking in creating environmentally-friendly places. Other lecture programs, including a panel discus- sion with I.M. Pei and Leslie Robertson, appealed to diverse audiences. -

Defining Architectural Design Excellence Columbus Indiana

Defining Architectural Design Excellence Columbus Indiana 1 Searching for Definitions of Architectural Design Excellence in a Measuring World Defining Architectural Design Excellence 2012 AIA Committee on Design Conference Columbus, Indiana | April 12-15, 2012 “Great architecture is...a triple achievement. It is the solving of a concrete problem. It is the free expression of the architect himself. And it is an inspired and intuitive expression of the client.” J. Irwin Miller “Mediocrity is expensive.” J. Irwin Miller “I won’t try to define architectural design excellence, but I can discuss its value and strategy in Columbus, Indiana.” Will Miller Defining Architectural Design Excellence..............................................Columbus, Indiana 2012 AIA Committee on Design The AIA Committee on Design would like to acknowledge the following sponsors for their generous support of the 2012 AIA COD domestic conference in Columbus, Indiana. DIAMOND PARTNER GOLD PARTNER SILVER PARTNER PATRON DUNLAP & Company, Inc. AIA Indianapolis FORCE DESIGN, Inc. Jim Childress & Ann Thompson FORCE CONSTRUCTION Columbus Indiana Company, Inc. Architectural Archives www.columbusarchives.org REPP & MUNDT, Inc. General Contractors Costello Family Fund to Support the AIAS Chapter at Ball State University TAYLOR BROS. Construction Co., Inc. CSO Architects, Inc. www.csoinc.net Pentzer Printing, Inc. INDIANA UNIVERSITY CENTER for ART + DESIGN 3 Table of Contents Remarks from CONFERENCE SCHEDULE SITE VISITS DOWNTOWN FOOD/DINING Mike Mense, FAIA OPTIONAL TOURS/SITES -

Grace La Is Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Principal of LA DALLMAN Architects

Grace La is Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Principal of LA DALLMAN Architects. La’s work is internationally recognized for the integration of architecture, engineering and landscape. Cofounded with James Dallman, LA DALLMAN is engaged in catalytic projects of diverse scale and type. Noted for works that expand the architect's agency in the civic recalibration of infrastructure, public space and challenging sites, LA DALLMAN was named as an Emerging Voice by the Architectural League of New York in 2010 and received the Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence Silver Medal in 2007. In 2011, LA DALLMAN was the first practice in the United States to receive the Rice Design Alliance Prize, an international award recognizing exceptionally gifted architects in the early phase of their career. LA DALLMAN has also been awarded numerous professional honors, including architecture and engineering awards, as well as prizes in international design competitions. LA DALLMAN’s built work includes the Kilbourn Tower, the Miller Brewing Meeting Center (original building by Ulrich Franzen), the University of Wisconsin‐Milwaukee (UWM) Hillel Student Center, the Ravine House, the Gradient House and the Great Lakes Future and City of Freshwater permanent science exhibits at Discovery World. The Crossroads Project transforms infrastructure for public use, including a 700‐foot‐long Marsupial Bridge, a bus shelter and a media garden. LA DALLMAN is currently commissioned to design additions to the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts (original building by Harry Weese and landscape by Dan Kiley), the 2013 Master Plan for the Menomonee Valley and the Harmony Project, a 100,000‐square‐foot hybrid arts building for professional dance, which includes a ballet school, a university dance program and a medical clinic. -

2012 Lwresume

Louis Wasserman & Associates AIA Architecture Landscape Architecture Architecture P.O.Box 11138 Telephone 414 271-6474 Planning Shorewood WI 53211 email: [email protected] Landscape Architecture web: www.louiswassermanandassociates.com Louis Wasserman Member of the American Institute of Architects and NCARB certified. Registration Licensed in Wisconsin and Illinois. Previously KY, MA, MO, MI, MN, OH, and IN.. Organizations AIA, Wisconsin AIA Director at Large for two years Education Master of Architecture, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Bachelor of Architecture, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois. Summa Cum Laude. Ecole des Beaux Artes, Unite Pedagogique d’Architecture 3, Versailles, France. Professional Experience Louis Wasserman & Associates. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Master Planning, Recreational Planning, Research, Commercial, LL Buildout, Historic Renovation, Institutional, Residential Projects. Historic Preservation. Benjamin Thompson Architects. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Design Architect for commercial revitalization, Embassy, Educational, Historic Preservation, Adaptive Reuse and Recreational projects. Cambridge Seven Associates. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Architect for Miami Transit Station, Designer for Educational and Recreational Facilities. Add Inc. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Architect for Lowell Boathouse, Designer for Institutional and Commercial Facilities. Jerome Butler, City Architect of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. Design Architect for adaptive reuse and revitalization -

ORAL HISTORY of CYNTHIA WEESE Interviewed by Judith K. De

ORAL HISTORY OF CYNTHIA WEESE Interviewed by Judith K. De Jong Complied under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture and Design The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 2007 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Outline of Topics vi Oral History 1 Selected References 47 Appendix: Curriculum Vitae 49 Index of Names and Buildings 52 iii PREFACE Cynthia Weese’s decision to become an architect was deeply influenced by the landscape of her childhood in Iowa, a few key buildings, and the strong support of her family. One of only a handful of women students, she excelled at Washington University in St. Louis, where she met mentors Joe Passoneau, Fumihiko Maki, Roger Montgomery, and Ben Weese. Upon moving to Chicago, Cynthia opened a small practice that focused on urban pioneers in North Side neighborhoods; later she worked for both landscape architect Joe Karr and architect Harry Weese. In 1977 she—along with Ben Weese—was a founding principal of what is now Weese Langley Weese, where she won multiple design awards and was widely published and exhibited. Her participation in the Chicago Eleven, her contributions as a founding member of Chicago Women in Architecture and the Chicago Architectural Club, and her leadership of the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects exemplify both her commitment to dialogue within the profession as well as outreach by architects to the broader community. -

REDISCOVERED Creating a Better Community

COLUMBUS, INDIANA REDISCOVERED Creating a better Community Steven R. Risting, AIA CSO Architects Columbus Area Visitors Center Columbus,Tour Guide training Indiana REDISCOVERED29 January 2013 Creating a better Community “First we shape our buildings, therefore, they shape us.” Winston Churchill Creating a better COMMUNITY with architectural design excellence LIVE WORK PLAY LEARN WORSHIP Columbus, Indiana REDISCOVERED Creating a better Community LIVE WORK PLAY LEARN WORSHIP St. Bartholomew Roman Catholic Church Steven R. Risting (Ratio Architects) 1999-2002 Columbus, Indiana REDISCOVERED Creating a better Community A daunng task to design in the shadows of recognized great architecture… Saarinen, Weese Columbus, Indiana REDISCOVERED Creating a better Community LIVE WORK PLAY LEARN WORSHIP About the people, COMMUNITY Columbus, Indiana REDISCOVERED Creating a better Community LIVE WORK PLAY LEARN WORSHIP AIA: a place of memory and inspiraon… integraon of city and architecture Integraon of architecture and landscape First Christian Church, Eliel Saarinen, 1942 North Christian Church, Eero Saarinen, 1964 (National Historic Landmark, 2000) (National Historic Landmark, 2000) Columbus, Indiana REDISCOVERED Creating a better Community LIVE WORK PLAY LEARN WORSHIP AIA: a place of “majestas” (majesty) and “mysterium” (mystery) First Baptist Church, 1965 (National Historic Landmark, 2000) St. Paul’s Episcopal Church renovation, Thomas Beeby, 2002 Columbus, Indiana REDISCOVERED Creating a better Community LIVE WORK PLAY LEARN WORSHIP Commons Office -

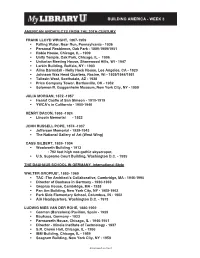

Building America - Week 3

BUILDING AMERICA - WEEK 3 AMERICAN ARCHITECTS FROM THE 20TH CENTURY FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, 1867-1959 • Falling Water, Bear Run, Pennsylvania - 1936 • Personal Residence, Oak Park - 1889-1909/1951 • Robie House, Chicago, IL - 1909 • Unity Temple, Oak Park, Chicago, IL - 1906 • Unitarian Meeting House, Shorewood Hills, WI - 1947 • Larkin Building, Buffalo, NY - 1903 • Aline Barnsdall - Holly Hock House, Los Angeles, CA - 1920 • Johnson Wax Head Quarters, Racine, WI - 1939/1944/1951 • Taliesin West, Scottsdale, AZ - 1938 • Price Company Tower, Bartlesville, OK - 1952 • Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, NY - 1959 JULIA MORGAN, 1872 -1957 • Hearst Castle at San Simeon - 1910-1919 • YWCA’s in California - 1900-1940 HENRY BACON, 1866 -1924 • Lincoln Memorial - 1922 JOHN RUSSELL POPE, 1874 -1937 • Jefferson Memorial - 1939-1943 • The National Gallery of Art (West Wing) CASS GILBERT, 1859- 1934 • Woolworth Building - 1913 - 792 feet high neo-gothic skyscraper, • U.S. Supreme Court Building, Washington D.C. - 1935 THE BAUHAUS SCHOOL IN GERMANY International Style WALTER GROPIUS*, 1883- 1969 • TAC -The Architect’s Collaborative, Cambridge, MA - 1946-1995 • Director of Bauhaus in Germany - 1930-1933 • Gropius House, Cambridge, MA - 1938 • Pan Am Building, New York City, NY - 1958-1963 • Park Side Elementary School, Columbus, IN - 1962 • AIA Headquarters, Washington D.C. - 1973 LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE, 1886-1969 • German (Barcelona) Pavilion, Spain - 1929 • Bauhaus, Germany - 1923 • Farnsworth House, Chicago, IL - 1946-1951 • Director - Illinois -

Holden Block 1027 West Madison Street

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Holden Block 1027 West Madison Street Preliminary and Final Landmark Recommendation Adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, March 3, 2011 CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Housing and Economic Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner Bureau of Planning and Zoning Historic Preservation Division Cover: The Holden Block at 1027 W. Madison St. is a four-story commercial loft building built in 1872. It is designed in the Italianate architectural style, faced with Buena Vista sandstone, and ornamented with a plethora of finely-crafted stone ornament concentrated around upper-floor windows. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is responsible for recommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the Landmarks Commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city permits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recommendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation process. Only language contained within a designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. HOLDEN BLOCK 1027 West Madison Street Built: 1872 Architect: Stephen Vaughn Shipman The Holden Block, a four-story building located on Chicago’s Near West Side, is an unusual- surviving Italianate “commercial block” from the 1870s. -

Modernism in Washington Brochure

MODERNISM IN WASHINGTON MODERNISM IN WASHINGTON The types of resources considered worthy of preservation have continually evolved since the earliest efforts aimed at memorializing the homes of our nation’s founders. In addition to sites associated with individuals or events, buildings and neighborhoods are now looked at not just as monuments to those who lived or worked in them, but as representative expressions of their time. In the past decade, increasing interest and attention has focused on buildings of the relatively recent past, those constructed in the mid-20th century. However, understanding – much less protecting – buildings and sites from the recent past presents several challenges. How do we distinguish which buildings are significant among such an overwhelming representation of a period? How do we appreciate the buildings of an era that often resulted in the destruction of significant 19th and early 20th century buildings, and that have come to be associated with sprawl or failed urban redevelopment experiments? How can we think critically about evaluating and possibly preserving buildings which are simply so … modern? Understanding what Modernism is and what it has meant is an important first step towards recognizing significant or representative buildings. This brochure offers a broad outline of the ideas and trends in the emergence and evolution of Modern design in Washington so that Modernism can be incorporated into discussions of our city’s history, culture, architecture and preservation. INTRODUCTION The term “Modernism” is generally used to describe various 20th century architectural trends that combine functionalism, redefined aesthetics, new technologies, and the rejection of historical precepts. Unlike its immediate predecessors, such as Art Deco and Streamlined Moderne, Modernism in the mid-20th century was not so much an architectural style as it was a flexible concept, adapted and applied in a wide variety of ways. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE the Architecture of Harry Weese, Public

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Architecture of Harry Weese, Public Lecture by Robert Bruegmann at the Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist, Chicago Tuesday, October 26, 2010 Seventeeth Church of Christ, Scientist, Chicago Designed by Harry Weese and Associates, 1968 Photo by Orlando Cabanban Printed with permission from W.W. Norton & Company Chicago, September 27, 2010 - On Tuesday, October 26, the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts will host a free lecture celebrating the release of The Architecture of Harry Weese, a new book by Robert Bruegmann and Kathleen Murphy Skolnik. The public is invited to experience the architecture of Harry Weese firsthand by joining Bruegmann for a lecture on the architect’s legacy in one of his most important buildings, the Church of Christ, Scientist, Chicago. Built in 1968, the church is a consummate example of the architect’s pioneering style and his significant contributions to Chicago’s architectural history. The lecture will be followed by a book signing. During a career that spanned half a century from the 1930s to the 1980s, Harry Weese (1915 - 1998) produced a large number of significant designs ranging from small but highly inventive houses to large urban scale commissions like the Washington, D.C. Metro system. As the first monograph solely devoted to Weese’s work, the book revives the reputation of a visionary architect. This book takes its place within a fast-growing revival of interest in the work of Weese and a number of his friends and contemporaries with shared assumptions and sensibilities, notably Eero Saarinen, Edward Larrabee Barnes, I. -

The 150 Favorite Pieces of American Architecture

The 150 favorite pieces of American architecture, according to the public poll “America’s Favorite Architecture” conducted by The American Institute of Architects (AIA) and Harris Interactive, are as follows. For more details on the winners, visit www.aia150.org. Rank Building Architect 1 Empire State Building - New York City William Lamb, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon 2 The White House - Washington, D.C. James Hoban 3 Washington National Cathedral - Washington, D.C. George F. Bodley and Henry Vaughan, FAIA 4 Thomas Jefferson Memorial - Washington D.C. John Russell Pope, FAIA 5 Golden Gate Bridge - San Francisco Irving F. Morrow and Gertrude C. Morrow 6 U.S. Capitol - Washington, D.C. William Thornton, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Charles Bulfinch, Thomas U. Walter FAIA, Montgomery C. Meigs 7 Lincoln Memorial - Washington, D.C. Henry Bacon, FAIA 8 Biltmore Estate (Vanderbilt Residence) - Asheville, NC Richard Morris Hunt, FAIA 9 Chrysler Building - New York City William Van Alen, FAIA 10 Vietnam Veterans Memorial - Washington, D.C. Maya Lin with Cooper-Lecky Partnership 11 St. Patrick’s Cathedral - New York City James Renwick, FAIA 12 Washington Monument - Washington, D.C. Robert Mills 13 Grand Central Station - New York City Reed and Stern; Warren and Wetmore 14 The Gateway Arch - St. Louis Eero Saarinen, FAIA 15 Supreme Court of the United States - Washington, D.C. Cass Gilbert, FAIA 16 St. Regis Hotel - New York City Trowbridge & Livingston 17 Metropolitan Museum of Art – New York City Calvert Vaux, FAIA; McKim, Mead & White; Richard Morris Hunt, FAIA; Kevin Roche, FAIA; John Dinkeloo, FAIA 18 Hotel Del Coronado - San Diego James Reid, FAIA 19 World Trade Center - New York City Minoru Yamasaki, FAIA; Antonio Brittiochi; Emery Roth & Sons 20 Brooklyn Bridge - New York City John Augustus Roebling 21 Philadelphia City Hall - Philadelphia John McArthur Jr., FAIA 22 Bellagio Hotel and Casino - Las Vegas Deruyter Butler; Atlandia Design 23 Cathedral of St. -

Written Transcript

The Cultural Landscape Foundation® Pioneers of American Landscape Design® ___________________________________ JOE KARR ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ___________________________________ Interviews Conducted May 23-24, 2017 By Charles A. Birnbaum, FASLA, FAAR Table of Contents PRELUDE .......................................................................................................................................... 5 BIOGRAPHY ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Childhood .................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Growing up in Northern Illinois ............................................................................................................................ 6 Early Experiences of Landscape ........................................................................................................................ 6 Rock River Valley ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Early Experiences of Art ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Drawing ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Making