Mid-Century Modern Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture

1 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture Fall 2011 Contents “Permanent Change” symposium review by Brennan Buck 2 David Chipperfield in Conversation Anne Tyng: Inhabiting Geometry 4 Grafton Architecture: Shelley McNamara exhibition review by Alicia Imperiale and Yvonne Farrell in Conversation New Users Group at Yale by David 6 Agents of Change: Geoff Shearcroft and Sadighian and Daniel Bozhkov Daisy Froud in Conversation Machu Picchu Artifacts 7 Kevin Roche: Architecture as 18 Book Reviews: Environment exhibition review by No More Play review by Andrew Lyon Nicholas Adams Architecture in Uniform review by 8 “Thinking Big” symposium review by Jennifer Leung Jacob Reidel Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern 10 “Middle Ground/Middle East: Religious review by Enrique Ramirez Sites in Urban Contexts” symposium Pride in Modesty review by Britt Eversole review by Erene Rafik Morcos 20 Spring 2011 Lectures 11 Commentaries by Karla Britton and 22 Spring 2011 Advanced Studios Michael J. Crosbie 23 Yale School of Architecture Books 12 Yale’s MED Symposium and Fab Lab 24 Faculty News 13 Fall 2011 Exhibitions: Yale Urban Ecology and Design Lab Ceci n’est pas une reverie: In Praise of the Obsolete by Olympia Kazi The Architecture of Stanley Tigerman 26 Alumni News Gwathmey Siegel: Inspiration and New York Dozen review by John Hill Transformation See Yourself Sensing by Madeline 16 In The Field: Schwartzman Jugaad Urbanism exhibition review by Tributes to Douglas Garofalo by Stanley Cynthia Barton Tigerman and Ed Mitchell 2 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 David Chipperfield David Chipperfield Architects, Neues Museum, façade, Berlin, Germany 1997–2009. -

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

Aspects of Architectural Drawings in the Modern Era

Acknowledgments Fellows of the Program (h Architecture Society 1oiLl13l I /113'1 l~~g \JI ) C,, '"l.,. This exhibition of drawings by European and American archi Darcy Bonner Exhibition tects of the Modern Movement is the fifth in The Art Institute of Laurence Booth The Modern Movement: Selections from the Chicago's Architecture in Context series. The theme of Modern William Drake, Jr. Permanent Collection April 9 - November 20, 1988 ism became a viable exhibition topic as the Department of Archi Lonn Frye Galleries 9 and 10, The Art Institute of Chicago tecture steadily strengthened over the past five years its collection Michael Glass Lectures of drawings dating from the first four decades of this century. In Joseph Gonzales Dennis P. Doordan, Assistant Professor of Architec the case of some architects, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Bruce Gregga tural History, University of Illinois at Chicago, "The Ludwig Hilberseimer, Paul Schweikher, William Deknatel, and Marilyn and Modern Movement in Architectural Drawin gs," James Edwin Quinn, the drawings represented in this exhibition Wilbert Hasbrouck Wednesday, April 27, 1988,at 2:30 p.m. , at The Art are only a small selection culled from the large archives of their Scott Himmel Institute of Chicago. Admission by ticket only. For reservations, telephone 443-3915. drawings that have been donated to the Art Institute. In the case Helmut Jahn of European Modernists whose drawings rarely come on the mar James L. Nagle Steven Mansbach, Acting Associate Dean of the ket, such as Eric Mendelsohn, J. J. P. Oud, and Le Corbusier, the Gordon Lee Pollock Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Na Art Institute has acquired drawings on an individual basis as John Schlossman tional Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., "Reflections works by these renowned architects have become available. -

333 North Michigan Buildi·N·G- 333 N

PRELIMINARY STAFF SUfv1MARY OF INFORMATION 333 North Michigan Buildi·n·g- 333 N. Michigan Avenue Submitted to the Conwnission on Chicago Landmarks in June 1986. Rec:ornmended to the City Council on April I, 1987. CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development J.F. Boyle, Jr., Commissioner 333 NORTH MICIDGAN BUILDING 333 N. Michigan Ave. (1928; Holabird & Roche/Holabird & Root) The 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING is one of the city's most outstanding Art Deco-style skyscrapers. It is one of four buildings surrounding the Michigan A venue Bridge that defines one of the city' s-and nation' s-finest urban spaces. The building's base is sheathed in polished granite, in shades of black and purple. Its upper stories, which are set back in dramatic fashion to correspond to the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, are clad in buff-colored limestone and dark terra cotta. The building's prominence is heightened by its unique site. Due to the jog of Michigan Avenue at the bridge, the building is visible the length of North Michigan Avenue, appearing to be located in the center of the street. ABOVE: The 333 North Michigan Building was one of the first skyscrapers to take advantage of the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, which encouraged the construction of buildings with setback towers. This photograph was taken from the cupola of the London Guarantee Building. COVER: A 1933 illustration, looking south on Michigan Avenue. At left: the 333 North Michigan Building; at right the Wrigley Building. 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING 333 North Michigan Avenue Architect: Holabird and Roche/Holabird and Root Date of Construction: 1928 0e- ~ 1QQ 2 00 Cft T Dramatically sited where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River are four build ings that collectively illustrate the profound stylistic changes that occurred in American architecture during the decade of the 1920s. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

The Orchard Official Neighborhood Guide

OFFICIAL GUIDE TO LINCOLN PARK WELCOME 3 A SUNRISE WORKOUT ALONG LAKE MICHIGAN. AN AFTERNOON PLAY DATE AT THE NATURE MUSEUM. THIS IS LINCOLN PARK. A DINNER WORTH ITS WEIGHT IN MICHELIN STARS. EXPLORE LINCOLN PARK 5 FAMILY FUN GIRLS’ DAY Enjoy breakfast at Lincoln Park Meet the girls for a mimosa brunch staple, Batter & Berries. at Summer House Santa Monica. The Perfect Day BATTERANDBERRIES.COM SUMMERHOUSESM.COM/CHICAGO IN LINCOLN PARK Spend the rest of the morning at Wander your way along Armitage Green City Market where you can Avenue for a mix of local boutiques shop for produce from local farmers, and national names, including Art One neighborhood, endless itineraries. Whether you’re planning a magical date night or a watch a live chef demonstration, or Effect, Kiehl’s, Peruvian Connection, celebratory afternoon with the girls, or you need to focus on self-care or spend quality time with the make a craft with the kids. and Serena & Lily family, Lincoln Park has something for everyone. With such diversity in scenery, from the lakefront GREENCITYMARKET.ORG and endless number of parks, to boutique shopping and museums, there is no limit to what a day in Wind down with happy hour at Stay out by the lake and enjoy the Quality Crab & Oyster Bah. afternoon at Lincoln Park Zoo. Lincoln Park looks like. QUALITYCRABANDOYSTERBAH.COM LPZOO.ORG Summer House Santa Monica DATE NIGHT SELF-CARE DAY Book a cooking class for two at Begin the day with an early morning The Social Table. workout or private training session at THESOCIALTABLE.COM Equinox Lincoln Common. -

Hotel-Map.Pdf

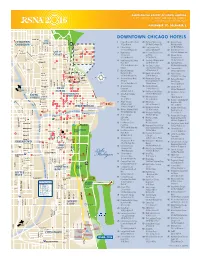

RADIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA 102ND SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY AND ANNUAL MEETING McCORMICK PLACE, CHICAGO NOVEMBER 27 – DECEMBER 2 DOWNTOWN CHICAGO HOTELS OLD CLYBOURN 1 Palmer House Hilton Hotel 28 Fairmont Hotel Chicago 61 Monaco Chicago, CORRIDOR TOWN 17 East Monroe 200 North Columbus Dr. A Kimpton Hotel 2 Hilton Chicago 29 Four Seasons Hotel 225 North Wabash 23 720 South Michigan Ave. 120 East Delaware Pl. 62 Omni Chicago Hotel GOLD 60 70 3 Hyatt Regency 30 Freehand Chicago Hostel 676 North Michigan Ave. COAST 29 87 38 66 Chicago Hotel and Hotel 63 Palomar Chicago, 89 68 151 East Wacker Dr. 19 East Ohio St. A Kimpton Hotel 80 47 4 Hyatt Regency McCormick 31 The Gray, A Kimpton Hotel 505 North State St. Place Hotel 122 W. Monroe St. 64 Park Hyatt Hotel 2233 South Martin Luther 32 The Gwen, a Luxury 800 North Michigan Ave. King Dr. Collection Hotel, Chicago 65 Peninsula Hotel 5 Marriott Downtown 521 North Rush St. 108 East Superior St. 79 Magnificent Mile 33 Hampton Inn & Suites 66 Public Chicago 86 540 North Michigan Ave. 33 West Illinois St. 78 1301 North State Pkwy. Sheraton Chicago Hotel Hampton Inn Chicago 75 6 34 67 Radisson Blu Aqua & Towers Downtown Magnificent Mile 73 Hotel Chicago 301 East North Water St. 160 East Huron 221 N. Columbus Dr. 64 7 AC Hotel Chicago 35 Hampton Majestic 68 Raffaello Hotel NEAR 65 59 Downtown 22 West Monroe St. 201 East Delaware Pl. 62 10 34 42 630 North Rush St. NORTH 36 Hard Rock Hotel Chicago 69 Renaissance Chicago 46 21 MAGNIFICENT 230 North Michigan Ave. -

Lincoln Park Community Data Snapshot Chicago Community Area Series August 2021 Release

Lincoln Park Community Data Snapshot Chicago Community Area Series August 2021 Release 1 Community Data Snapshot | Lincoln Park About the Community Data Snapshots The Community Data Snapshots is a series of data profiles for every county, municipality, and Chicago Community Area (CCA) within the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) seven-county northeastern Illinois region. The snapshots primarily feature data from the American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates, although other data sources include the U.S. Census Bureau, Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA), Illinois Department of Employment Security (IDES), Illinois Department of Revenue (IDR), HERE Technologies, and CMAP itself. CMAP publishes updated Community Data Snapshots annually to reflect the most recent data available. The latest version can always be found at cmap.illinois.gov/data/community-snapshots. The underlying data can be downloaded from the CMAP Data Hub. Please direct any inquiries to [email protected]. To improve the Community Data Snapshots in the future, CMAP wants to hear from you! Please take a quick survey to describe how you use this data and what you would like to see in next year’s snapshots. User Notes Definitions For data derived from the ACS, the Community Data Snapshots uses terminology based on the ACS subject definitions. Margins of Error The ACS is a sample-based data product. Exercise caution when using data from low-population communities, as the margins of error are often large compared to the estimates. For more details, please refer to the ACS sample size and data quality methodology. Regional Values Regional values are estimated by aggregating ACS data for the seven counties that compose the CMAP region. -

Acc.16 Shuttle Bus Service

ACC.16 SHUTTLE BUS SERVICE Shuttle bus services to and from the ACC.16 hotels and McCormick Place are provided for individuals who made hotel reservations through Experient Inc., the official ACC.16 housing company. There will be no shuttle service on Friday, April 1. Saturday, April 2 – Monday, April 4 Departures from Hotels ..................................... 6:00 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. No shuttle service provided .............................9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. Departures from Convention Center............5:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. McCormick Place is the transfer point for all routes. Hyatt McCormick hotel is within walking distance to McCormick Place and shuttle bus service will not be provided. If you require a special-needs shuttle, please contact [email protected] to make arrangements. Please note on Sunday, April 3 from 6 a.m. – 9 a.m., there will be street closures throughout Chicago due to the Shamrock Shuffle 8K Race. The closures will impact all traffic, including the ACC.16 shuttle routes. Be sure to allow additional travel time to get to ACC.16 on Sunday morning. Please review the sign in your hotel lobby for updated information and alternate boarding locations where applicable. EVENT TRANSPORTATION Clinical Focus Sessions (Saturday, April 2 and Sunday, April 3) A single departure at 8:45 p.m. will be offered for all routes with return service to hotels. Convocation (Monday, April 4) Limited service for all routes will be offered from 7:30 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. The last departure from McCormick Place going to hotels is 9:30 p.m. -

NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Contents

NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Contents 1 Message from the Chair The National Building Museum explores the world and the Executive Director we build for ourselves—from our homes, skyscrapers and public buildings to our parks, bridges and cities. 2 Exhibitions Through exhibitions, education programs and publications, the Museum seeks to educate the 12 Education public about American achievements in architecture, design, engineering, urban planning, and construction. 20 Museum Services The Museum is supported by contributions from 22 Development individuals, corporations, foundations, associations, and public agencies. The federal government oversees and maintains the Museum’s historic building. 24 Contributors 30 Financial Report 34 Volunteers and Staff cover / Looking Skyward in Atrium, Hyatt Regency Atlanta, Georgia, John Portman, 1967. Photograph by Michael Portman. Courtesy John Portman & Associates. From Up, Down, Across. NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 The 2003 Festival of the Building Arts drew the largest crowd for any single event in Museum history, with nearly 6,000 people coming to enjoy the free demonstrations “The National Building Museum is one of the and hands-on activities. (For more information on the festival, see most strikingly designed spaces in the District. page 16.) Photo by Liz Roll But it has a lot more to offer than nice sightlines. The Museum also offers hundreds of educational programs and lectures for all ages.” —Atlanta Business Chronicle, October 4, 2002 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR AND THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR responsibility they are taking in creating environmentally-friendly places. Other lecture programs, including a panel discus- sion with I.M. Pei and Leslie Robertson, appealed to diverse audiences. -

Defining Architectural Design Excellence Columbus Indiana

Defining Architectural Design Excellence Columbus Indiana 1 Searching for Definitions of Architectural Design Excellence in a Measuring World Defining Architectural Design Excellence 2012 AIA Committee on Design Conference Columbus, Indiana | April 12-15, 2012 “Great architecture is...a triple achievement. It is the solving of a concrete problem. It is the free expression of the architect himself. And it is an inspired and intuitive expression of the client.” J. Irwin Miller “Mediocrity is expensive.” J. Irwin Miller “I won’t try to define architectural design excellence, but I can discuss its value and strategy in Columbus, Indiana.” Will Miller Defining Architectural Design Excellence..............................................Columbus, Indiana 2012 AIA Committee on Design The AIA Committee on Design would like to acknowledge the following sponsors for their generous support of the 2012 AIA COD domestic conference in Columbus, Indiana. DIAMOND PARTNER GOLD PARTNER SILVER PARTNER PATRON DUNLAP & Company, Inc. AIA Indianapolis FORCE DESIGN, Inc. Jim Childress & Ann Thompson FORCE CONSTRUCTION Columbus Indiana Company, Inc. Architectural Archives www.columbusarchives.org REPP & MUNDT, Inc. General Contractors Costello Family Fund to Support the AIAS Chapter at Ball State University TAYLOR BROS. Construction Co., Inc. CSO Architects, Inc. www.csoinc.net Pentzer Printing, Inc. INDIANA UNIVERSITY CENTER for ART + DESIGN 3 Table of Contents Remarks from CONFERENCE SCHEDULE SITE VISITS DOWNTOWN FOOD/DINING Mike Mense, FAIA OPTIONAL TOURS/SITES