“Time of Dispersal:” Elections and Memory of War in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Full Report

2016 Elections in Somalia - The Rise of the New Somali Women's Political Movements The Somali Institute for Development and Research Analysis (SIDRA) Garowe, Puntland State of Somalia Cell Phone: +252-907-794730 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.sidrainstitute.org This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License (CC BY-NC 4.0) Attribute to: Somali Institute for Development & Research Analysis 2016 A note of Appreciation Many Somali women freely provided their time to take part in the surveys, focus group discussions and interviews for this study and thereby helping us collect quality data that allowed us to make sound scientific analysis. Without their contributions, this study would not have reached its findings. This study was self funded by SIDRA and would not have materialized without the sacrifice of keeping aside other cost to allocate resources for this study. Finally, this study would not have come to be without the tireless efforts of SIDRA staff through the direction of Sahro Koshin, SIDRA Head of Programmes and leadership of Guled Salah, SIDRAs Executive Director. Many other people supported this study in different ways and made it a success. SIDRA whole heartedly appreciates all these people. Page | 2 2016 Elections in Somalia - The Rise of the New Somali Women's Political Movements Table of content EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND -

Somalia Country Report BTI 2012

BTI 2012 | Somalia Country Report Status Index 1-10 1.22 # 128 of 128 Political Transformation 1-10 1.27 # 128 of 128 Economic Transformation 1-10 1.18 # 128 of 128 Management Index 1-10 1.51 # 127 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2012. The BTI is a global assessment of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economy as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — Somalia Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. © 2012 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2012 | Somalia 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 9.3 HDI - GDP p.c. $ - Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.3 HDI rank of 187 - Gini Index - Life expectancy years 51 UN Education Index - Poverty3 % - Urban population % 37.4 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 72.4 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2011. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Over the last two years, Somalia experienced ongoing violence and a continuous reconfiguration of political and military forces. During a United Nations brokered peace process in Djibouti, the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) reconciled with one of its opponents, the moderate Djibouti wing of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS-D). -

HAB Represents a Variety of Sources and Does Not Necessarily Express the Views of the LPI

ei January-February 2017 Volume 29 Issue 1 2017 elections: Making Somalia great again? Contents 1. Editor's Note 2. Somali elections online: View from Mogadishu 3. Somalia under Farmaajo: Fresh start or another false dawn? 4. Somalia’s recent election gives Somali women a glimmer of hope 5. ‘Regional’ representation and resistance: Is there a relationship between 2017 elections in Somalia and Somaliland? 6. Money and drought: Beyond the politico-security sustainability of elections in Somalia and Somaliland 1 Editorial information This publication is produced by the Life & Peace Institute (LPI) with support from the Bread for the World, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and Church of Sweden International Department. The donors are not involved in the production and are not responsible for the contents of the publication. Editorial principles The Horn of Africa Bulletin is a regional policy periodical, monitoring and analysing key peace and security issues in the Horn with a view to inform and provide alternative analysis on on-going debates and generate policy dialogue around matters of conflict transformation and peacebuilding. The material published in HAB represents a variety of sources and does not necessarily express the views of the LPI. Comment policy All comments posted are moderated before publication. Feedback and subscriptions For subscription matters, feedback and suggestions contact LPI’s regional programme on HAB@life- peace.org For more LPI publications and resources, please visit: www.life-peace.org/resources/ ISSN 2002-1666 About Life & Peace Institute Since its formation, LPI has carried out programmes for conflict transformation in a variety of countries, conducted research, and produced numerous publications on nonviolent conflict transformation and the role of religion in conflict and peacebuilding. -

State Fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: a Contrast in Peace and State Building

AUGUST 2018 State fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: A contrast in peace and state building Mohamed Farah Hersi Mohamed Farah Hersi is the Director of the Academy for Peace and Development in Hargeisa, Somaliland About the commission The LSE-Oxford Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development was launched in March 2017 to guide policy to combat state fragility. The commission, established under the auspices of the International Growth Centre, is sponsored by LSE and University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government. It is funded from the LSE KEI Fund and the British Academy’s Sustainable Development Programme through the Global Challenges Research Fund. Front page image: Mohamed958543 | Wikipedia 2 State fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: A contrast in peace and state building Contents Introduction 4 The rise and fall of pan-Somalism 6 The nexus between state legitimacy, and security and conflict 9 Political compromise and conflict: Undermining state effectiveness 13 Risky business: Private sector development amid insecurity 16 Living on the edge with few safety nets 19 Somali state fragility: Regional and international dynamics 20 Conclusion 23 Bibliography 25 3 State fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: A contrast in peace and state building Introduction The region inhabited by Somali-speaking people covers the northeast tip of Africa. During colonialism, this area was divided between European powers, separating the Somali people into five territories: Italian Somalia (today’s 1 Somalia), British Somaliland (today’s Somaliland), French Somaliland (today’s Djibouti), and notable Somali enclaves in Ethiopia’s Ogaden region and Kenya’s North Eastern province. Pan-Somali nationalism long hoped to overcome these colonial divides and unite all Somali peoples in a single nation. -

Peace Negotiations in Africa

2. Peace negotiations in Africa • Thirteen peace processes and negotiations were identified in Africa throughout 2020, accounting for 32.5% of the 40 peace processes worldwide. • The chronic deadlock and paralysis in diplomatic channels to address the Western Sahara issue favoured an escalation of tension at the end of the year. • At the end of 2020, the parties to the conflict in Libya signed a ceasefire agreement and the political negotiations tried to establish a transitional government, but doubts remained about the general evolution of the process. • In Mozambique, the Government and RENAMO made progress in implementing the DDR program envisaged in the 2019 peace agreement. • The first direct talks were held between the government of Cameroon and a part of the secessionist movement led by the historical leader Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe to try to reach a ceasefire agreement. • In Sudan, the government and the rebel coalition SRF and the SLM/A-MM signed a historic peace agreement that was not endorsed by other rebel groups such as the SPLM-N al-Hilu and the SLM/A-AW. • In South Sudan, the transitional government was formed and peace talks were held with the armed groups that had not signed the 2018 peace agreement. This chapter analyses the peace processes and negotiations in Africa in 2020. First, it examines the general characteristics and trends of peace processes in the region, then it delves into the evolution of each of the cases throughout the year, including references to the gender, peace and security agenda. At the beginning of the chapter, a map is included that identifies the African countries that were the scene of negotiations during 2020. -

Download the Transcript

SOMALIA-2021/05/21 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION WEBINAR ELECTIONS AND CRISES IN SOMALIA AND ETHIOPIA Washington, D.C. Thursday, May 20, 2021 PARTICIPANTS: Moderator: VANDA FELBAB-BROWN Senior Fellow and Director, Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors The Brookings Institution Panelists: ABDIRAHMAN AYNTE Co-founder and Managing Director Laasfort Consulting Group BRONWEN MORRISON Senior Director Center for Global Security and Stabilization Dexis Consulting Group LIDET TADESSE Policy Officer, Security Resilience Programme European Centre for Development Policy Management * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 SOMALIA-2021/05/21 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MS. FELBAB-BROWN: Good morning. Good afternoon. I am Vanda Felbab-Brown, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and director of the Brookings Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors and co-director of our Africa Security Initiative. I am delighted that you are all joining us today for our webinar on Crises and Elections in Ethiopia and Somalia and the regional setting of Horn of Africa, a very important issue that has been very dramatic and visibly in the news and, of course, unfolding in very important ways in the region. We have an absolutely terrific panel to discuss those very complex, very important issues with us that I will introduce in a minute. You know, I mentioned that Ethiopia and Somalia have been going through some very dramatic events in the past few months including, in the case of Somalia in the past few days and weeks. There are, of course, more dramatic changes in both countries taking place in the past few years such as in the past five years that have preceded those dramatic crises and to some extent, influenced them to other extent, but have not been able to prevent them. -

Somalia's Possible Political Transition Option in 2020/2021

Somalia’s Possible Political Transition Option in 2020/2021 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 4 ELECTION IN CONUNDRUM (2020/2021) ....................... 6 PERFORMANCE OF FGS2 ON ELECTIONS ....................... 8 FEASIBLE ELECTORAL OPTION ........................................ 11 ELECTORAL OPTION PROPOSAL ..................................... 12 EXISTING CONCERNS ......................................................... 15 CRAFTING POLITICAL AGREEMENT ................................ 16 Somalia’s Possible Political Transition Option in 2020/2021 2 ACRONYM FMS Federal Member State FP Federal Parliament HoP House of People NLF National Leaders Forum OPOV One-Person-one-Vote PC Provisional Constitution SPA Somali Public Agenda TFG Transitional Federal Government TNP Transitional National Parliament TNG Transitional Nationa Government FG S1 Federal Government of Somalia, 2012-2017 FG S2 Federal Government of Somalia, 2017-2021 UH Uppers House Somalia’s Possible Political Transition Option in 2020/2021 3 INTRODUCTION One of the most contentious issue in Somalia after the collapse of the central state, and subsequent efforts to reconstitute the nation (1991-2000), has been to strike an agreement on an interim representation model that would be used to establish an interim national governing authority, which would then lead the rebuilding process. The Somali Peace and Reconciliation Conference hosted by the Djibouti Government in 2000, and attended by delegates representing Somali communities agreed that the allocation of seats for the Transitional National Parliament be based on a clan power sharing model dubbed “4.5”. Using this agreed model, the first Transitional National Parliament (TNP) of 245 MPs (Later become 275 in 2004, Embagathi, Kenya) was inaugurated in Djibouti on 13th August 2000. The TNP elected H. E. Abdi-Qasim Salad as the interim president on 25th August 2000 who then appointed a Prime Minister on 8th October 2000 in Djibouti. -

Elections in Somalia and Somaliland

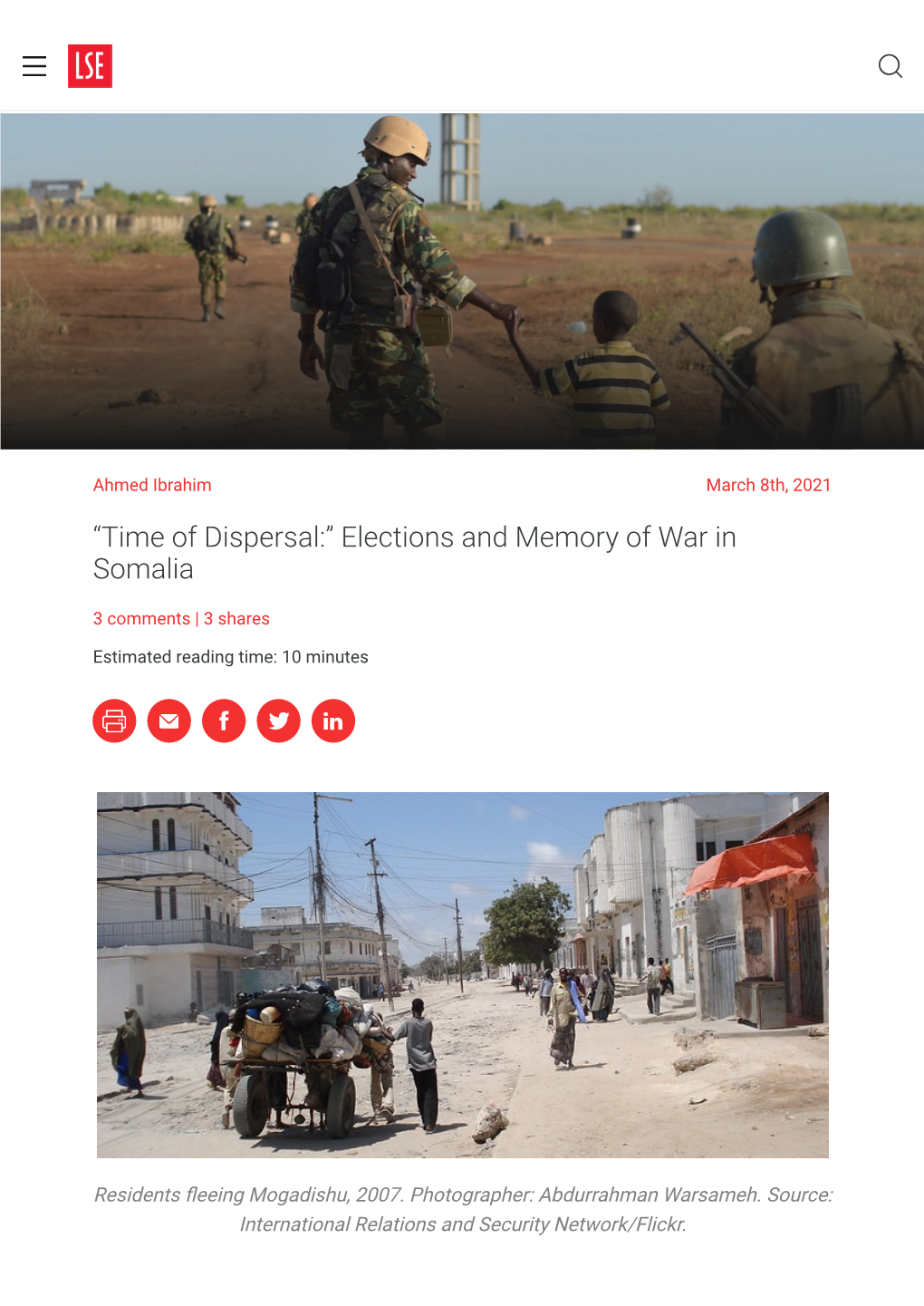

The Elections in Somalia and Somaliland Image 1 Credit: REUTERS/Feisal Omar. Protesters demonstrate against Somalia's President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed on the streets of Yaqshid district of Mogadishu, Somalia April 25, 2021 Introduction On 24 May, political leaders in Somalia agreed on a framework for the national elections after delays triggered a crisis. Chairwoman of the electoral commission Halimo Ismail stated the lengthy delay of the elections was due to “significant technical and security challenges.” Of the new deal prime minister Hussein Roble said “my dear brothers, politicians, whatever you need is in front of me. Do not search in other places. Let's all forgive one another, and I ask you to forgive me”. The agreement was signed by the prime minister and the leaders of 5 regional states. It set out a path for indirect parliamentary elections to start within 60 days, with each region designating two venues to allow clan elders and clan representatives to select lawmakers to the lower house. Parliament had also voted to extend president Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed’s term by two years and for the country to hold its future polls under a one-person-one-vote system. However, the move was rejected by the senate, prime minister, 1 The Elections in Somalia and Somaliland opposition leaders and four of the country’s six federal member states, leading to a standoff in the capital. With the stalemate in Mogadishu overcome and a general accord reached, Roble has said that the government is committed to moving forward and implementing the agreement; “my government is reassuring to the country’s political stakeholders and to the Somali people that my government will hold free and fair indirect elections in line with this agreement” adding “of course, we are all responsible to ensure women get their 30% quota (of positions)”. -

Women, Peace and Security in Somalia: Implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325

Women, Peace and Security in Somalia: Implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 A UN-INSTRAW Background Paper August 2008 The United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (UN-INSTRAW) promotes applied research on gender, facilitates information sharing, and supports capacity-building through networking mechanisms and multi-stakeholder partnerships with UN agencies, governments, academia and civil society. Associazione Diaspora e Pace (ADEP) is an association of Somali women living Italy that works for the empowerment of Somali women, both in Somali and as migrants in the Diaspora, in collaboration with the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and local authorities. Women, Peace and Security in Somalia: Implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 A UN-INSTRAW Background Paper Lead author: Toiko Tõnisson Kleppe UN-INSTRAW Responsible: Hilary Anderson-Taborga Reviewers: Nicola Popovic, Marian Ismail and Farhia Aidid Aden United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (UN-INSTRAW) César Nicolás Penson 102-A Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Phone: 1-809-685-2111 Fax: 1-809-685-2117 Email: [email protected] Webpage: http://www.un-instraw.org Copyright 2008 All rights reserved Acknowledgements UN-INSTRAW and the author would like to thank the members of the Associazione Diaspora e Pace (ADEP) for their input and comments, and for their practical and theoretical work with the project: “Gender and Peace in Somalia – Implementation of Resolution 1325.” The seven members of ADEP are Faduma Abdulle, Ghani Adam, Farhia Aidid Aden, Sareeda Cali, Marian Ismail, Fahma Said Abdikarin and Lul Mohamed Osman. The author would also like to thank the participants of the two project seminars in Italy for their contributions. -

Mr. President, Distinguished Members of the Council

As delivered Statement by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General, James Swan, to the Security Council on the Situation in Somalia 25 May 2021 Mr. President, Distinguished Members of the Council, Thank you for the opportunity to brief on the situation in Somalia. I am pleased do so together again with the Special Representative of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission for Somalia, Ambassador Francisco Madeira. This underscores the importance of the relationship between our two organisations in Somalia. AMISOM continues to play a critical role in Somalia every day, and I commend the bravery and determination of Somali and AMISOM forces as they advance peace and security in the country. I also look forward to the comments of the Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Somalia, His Excellency Mohammed Abdirizak. Mr. President, The political process to implement elections in Somalia has faced many obstacles in recent months. Talks between Federal Government and Federal Member State leaders that began in March regrettably broke down in early April. The House of the People of the Somali Parliament then adopted a “Special Law” abandoning the 17 September electoral agreement, reverting to a one-person-one-vote model, and extending the mandates of current office holders for up to two more years. Opposition to these moves led to the mobilization of militias and exposed divisions within Somali security forces. Violent clashes ensued on 25 April, risking broader conflict. Since then, Mr.. President, Somalia has come back from the brink of this worst-case scenario. Under intense pressure, the House of the People on 1 May reversed the Special Law, at the request of President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo.” The President subsequently empowered the Prime Minister to lead the FGS involvement in the electoral process, 1 As delivered including security arrangements and negotiations with FMSes. -

Hybridity, Local Ordering and the New Governing Rationalities of Peace and Security Interventions in Somalia

The ‘Turn to the Local’: Hybridity, local ordering and the new governing rationalities of peace and security interventions in Somalia Louise Wiuff Moe A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of Political Science and International Studies ii Abstract This thesis explores the potential and the limits of the ‘turn to the local’ in approaches to promote more inclusive forms of order and peace in conflict and post-conflict settings. As a consequence of the apparent limitations of liberal peace approaches that inform international peace and security interventions, recent discursive and practical shifts indicate a move away from imported institution-building and toward working through and upon local societal dynamics and so- called non-state actors. Thereby, logics of hybridity, non-linearity and resilience are incorporated into new governing rationalities of intervention policies. As a result, the concepts of ‘hybrid political orders’, ‘the everyday’ and ‘hybrid peace’- which were introduced into the debate as critiques of the liberal peace and state fragility discourses - no longer stand in univocal critical opposition to the liberal peacebuilding discourse. Rather, in the context of the ‘turn to the local’, hybridity is now both a concept informing critical peace and conflict analysis and a new terrain for policy discourse which opens up ‘the local’ as a key domain for intervention. This thesis examines how the ‘turn to the local’ and the associated approaches to hybrid governance work and are legitimized. It explores the agendas that underpin these emerging shifts and the accompanying dynamics and effects within local settings. -

Urbano2012.Pdf (3.226Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Imagining the Nation, Crafting the State: The Politics of Nationalism and Decolonisation in Somalia (1940-60) Annalisa Urbano Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2012 Imagining the Nation, Crafting the State Abstract The thesis offers a first-hand historically informed research on the trajectory of the making of the post-colonial state in Somalia (1940-60). It does so by investigating the interplay between the emergence and diffusion of national movements following the defeat of the Italians in 1941 and the establishment of a British Military Administration, and the process of decolonisation through a 10-year UN trusteeship to Italy in 1950. It examines the extent to which the features of Somali nationalism were affected/shaped by the institutional framework established by the UN mandate.