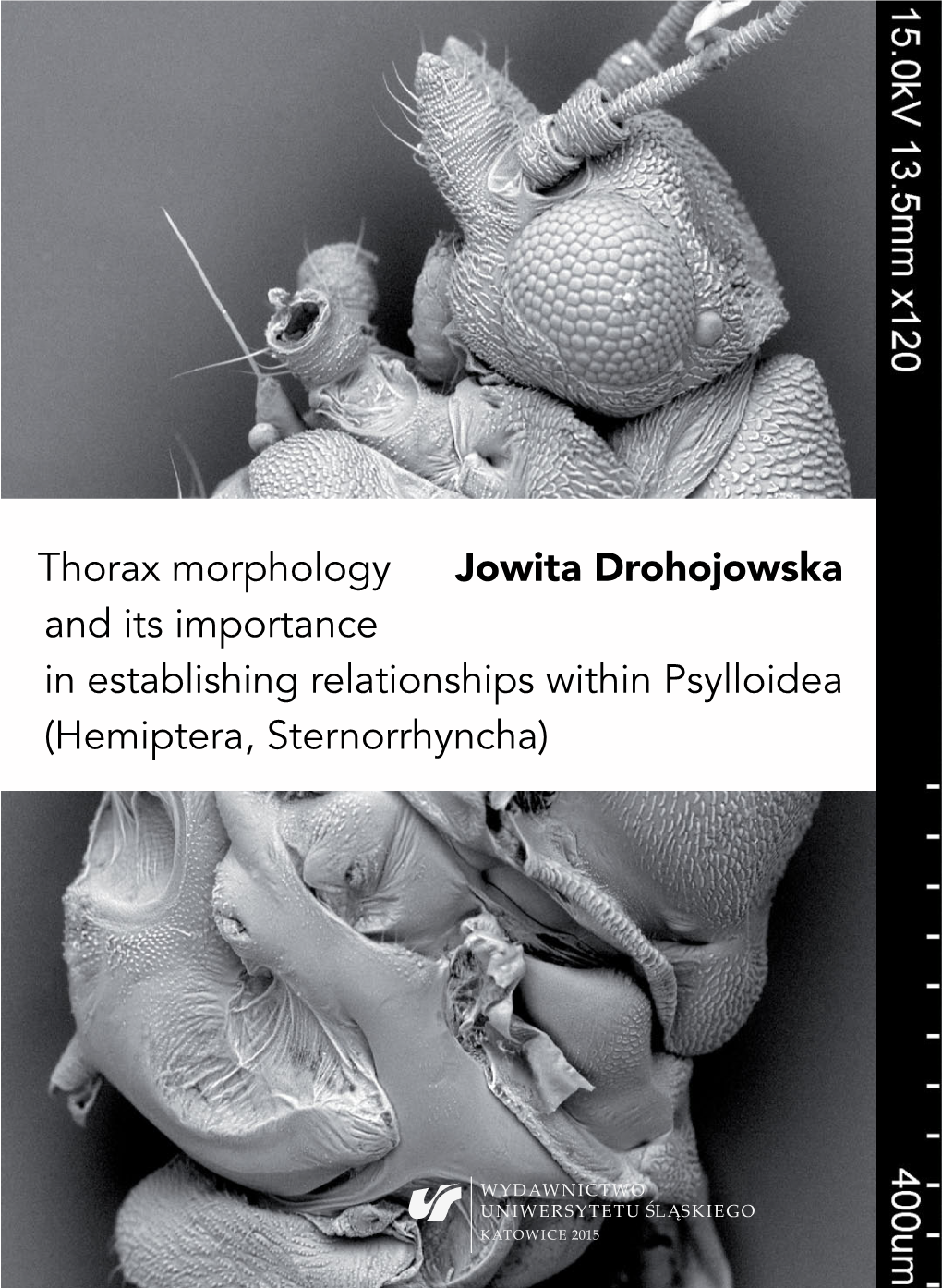

Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Release of the Insects Calophya Latiforceps

United States Department of Field Release of the Insects Agriculture Calophya latiforceps Marketing and Regulatory (Hemiptera: Calophyidae) and Programs Pseudophilothrips ichini Animal and Plant Health Inspection (Thysanoptera: Service Phlaeothripidae) for Classical Biological Control of Brazilian Peppertree in the Contiguous United States Environmental Assessment, May 2019 Field Release of the Insects Calophya latiforceps (Hemiptera: Calophyidae) and Pseudophilothrips ichini (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae) for Classical Biological Control of Brazilian Peppertree in the Contiguous United States Environmental Assessment, May 2019 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. -

Why Do the Galls Induced by Calophya Duvauae Scott on Schinus Polygamus (Cav.) Cabrera (Anacardiaceae) Change Colors?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 48 (2013) 111–122 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Biochemical Systematics and Ecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biochemsyseco Why do the galls induced by Calophya duvauae Scott on Schinus polygamus (Cav.) Cabrera (Anacardiaceae) change colors? Graciela Gonçalves Dias a, Gilson Rudinei Pires Moreira b, Bruno Garcia Ferreira a, Rosy Mary dos Santos Isaias a,* a Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Departamento de Botânica, Av. Antônio Carlos 6627, Campus Pampulha, Postal Office Box: 286, 31270-901 Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil b Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia, Av. Bento Gonçalves 9500, Campus do Vale, 91501-970 Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil article info abstract Article history: One of the galling herbivores associated to the superhost Schinus polygamus (Cav.) Cabrera Received 29 August 2012 (Anacardiaceae) is Calophya duvauae Scott (Hemiptera: Calophyidae). The galls are located Accepted 1 December 2012 on the adaxial surface of leaves and vary from red to green. The levels of their pigments Available online 16 January 2013 were herein investigated in relation to age. Samples were collected between June 2008 and March 2009, in a population of S. polygamus at Canguçu municipality, Rio Grande do Sul, Keywords: Brazil. Galls were separated by color, measured, dissected, and the instar of the inducer Extended phenotype was determined. The levels of photosynthetic (chlorophyll a and b, total chlorophylls, and Gall color changes Anthocyanin carotenoids) and protective pigments (anthocyanins) were also evaluated. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Irish Hemiptera and Small Orders

AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH HEMIPTERA AND SMALL ORDERS compiled by James P. O'Connor and Brian Nelson The Irish Biogeographical Society OTHER PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE FROM THE IRISH BIOGEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE IRISH BIOGEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY (A5 FORMAT) Number 1. Proceedings of The Postglacial Colonization Conference. D. P. Sleeman, R. J. Devoy and P. C. Woodman (editors). Published 1986. 88pp. Price €4 (Please add €4 for postage outside Ireland for each publication); Number 2. Biogeography of Ireland: past, present and future. M. J. Costello and K. S. Kelly (editors). Published 1993. 149pp. Price €15; Number 3. A checklist of Irish aquatic insects. P. Ashe, J. P. O’Connor and D. A. Murray. Published 1998. 80pp. Price €7; Number 4. A catalogue of the Irish Braconidae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonoidea). J. P. O’Connor, R. Nash and C. van Achterberg. Published 1999. 123pp. Price €6; Number 5. The distribution of the Ephemeroptera in Ireland. M. Kelly-Quinn and J. J. Bracken. Published 2000. 223pp. Price €12; Number 6. A catalogue of the Irish Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). J. P. O’Connor, R. Nash and Z. Bouček. Published 2000. 135pp. Price €10; Number 7. A catalogue of the Irish Platygastroidea and Proctotrupoidea (Hymenoptera). J. P. O’Connor, R. Nash, D. G. Notton and N. D. M. Fergusson. Published 2004. 110pp. Price €10; Number 8. A catalogue and index of the publications of the Irish Biogeographical Society (1977-2004). J. P. O’Connor. Published 2005. 74pp. Price €10; Number 9. Fauna and flora of Atlantic islands. Proceedings of the 5th international symposium on the fauna and flora of the Atlantic islands, Dublin 24 -27 August 2004. -

Pests of Cultivated Plants in Finland

ANNALES AGRICULTURAE FE,NNIAE Maatalouden tutkimuskeskuksen aikakauskirja Vol. 1 1962 Supplementum 1 (English edition) Seria ANIMALIA NOCENTIA N. 5 — Sarja TUHOELÄIMET n:o 5 Reprinted from Acta Entomologica Fennica 19 PESTS OF CULTIVATED PLANTS IN FINLAND NIILO A.VAPPULA Agricultural Research Centre, Department of Pest Investigation, Tikkurila, Finland HELSINKI 1965 ANNALES AGRICULTURAE FENNIAE Maatalouden tutkimuskeskuksen aikakauskirja journal of the Agricultural Researeh Centre TOIMITUSNEUVOSTO JA TOIMITUS EDITORIAL BOARD AND STAFF E. A. jamalainen V. Kanervo K. Multamäki 0. Ring M. Salonen M. Sillanpää J. Säkö V.Vainikainen 0. Valle V. U. Mustonen Päätoimittaja Toimitussihteeri Editor-in-chief Managing editor Ilmestyy 4-6 numeroa vuodessa; ajoittain lisänidoksia Issued as 4-6 numbers yearly and occasional supplements SARJAT— SERIES Agrogeologia, -chimica et -physica — Maaperä, lannoitus ja muokkaus Agricultura — Kasvinviljely Horticultura — Puutarhanviljely Phytopathologia — Kasvitaudit Animalia domestica — Kotieläimet Animalia nocentia — Tuhoeläimet JAKELU JA VAIHTOTI LAUKS ET DISTRIBUTION AND EXCHANGE Maatalouden tutkimuskeskus, kirjasto, Tikkurila Agricultural Research Centre, Library, Tikkurila, Finland ANNALES AGRICULTURAE FENNIAE Maatalouden tutkimuskeskuksen aikakauskirja 1962 Supplementum 1 (English edition) Vol. 1 Seria ANIMALIA NOCENTIA N. 5 — Sarja TUHOELÄIMET n:o 5 Reprinted from Acta Entomologica Fennica 19 PESTS OF CULTIVATED PLANTS IN FINLAND NIILO A. VAPPULA Agricultural Research Centre, Department of Pest Investigation, -

Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 561 SE 054 264 TITLE Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. Office of Technology Assessment. REPORT NO ISBN-0-16-042075-X; OTA-F-565 PUB DATE Sep 93 NOTE 409p.; Chapter One, The "Summary" has also been printed as a separate publication (OTA-F-566). ANAILABLE FROMU.S. Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328. PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Animals; Biotechnology; Case Studies; Decision Making; *Federal Legislation; Financial Support; Genetic Engineering; International Law; Natural Resources; *Plants (Botany); *Public Policy; Science Education; State Legislation; Weeds; Wildlife Management IDENTIFIERS Environmental Issues; Environmental Management; *Environmental Problems; Florida; Global Change; Hawaii; *Non Indigenous Speciez ABSTRACT Non-indigenous species (NIS) are common in the United States landscape. While some are beneficial, others are harmful and can cause significant economic, environmental, and health damage. This study, requested by the U.S. House Merchant Marine and Fisheries Committee, examined State and Federal policies related to these harmful NIS. The report is presented in 10 chapters. Chapter 1 identifies the issues and options related to the topic and a summary of the findings from the individual chapters that follow. Chapters 2 "The Consequences of NIS" and 3 "The Changing Numbers, Causes, and Rates of -

New Candidate for Biological Control of Brazilian Peppertree?

New Candidate for Biological Control of Brazilian Peppertree? by Lindsey R. Christ1 , James P. Cuda2, William A. Overholt3, and Marcelo D. Vitorino4 Fig. 1 [above]: University of Florida everal exotic plants introduced into Florida are graduate student Lindsey Christ wreaking havoc on native plant and animal commu- examining plants at the LAMPF, Snities. One such plant is the perennial, woody Bra- Santa Catarina, Brazil, for the zilian peppertree, Schinus terebinthifolius. Dr. James Cuda, presence of psyllid pit galls. Associate Professor in the Department of Entomology and Fig. 2 [right]: Pit galls of the psyllid Nematology and Lindsey Christ (Fig. 1), an entomology Calophya terebinthifolii on Brazilian peppertree leaflets in the field. graduate student in the School of Natural Resources and the Environment, believe insects are the key to controlling this invasive plant. Native to Brazil, Argentina, and Para- National Park. It wasn’t until 1990 that the plant was banned for guay and related to poison ivy and poison oak, Brazilian commercial sale in Florida. peppertree is one of the worst offenders. This woody shrub Now that Brazilian peppertree is firmly established in out-competes native species because of its fast growth, pro- Florida plant communities, measures have been taken to try lific seed production, vigorous resprouting, and tolerance and control the plant and keep it from spreading. It is currently to various growing conditions including salt, moisture, and controlled by herbicides, mechanical, and physical methods. shade. Also called Florida Holly or Christmasberry, Brazil- A more sustainable approach for managing exotic invasive ian peppertree was planted as an ornamental because of plants is integrating conventional control measures with its attractive green leaves and red fruits that ripen in De- classical biological control. -

Two New Species, Synthesis and Identification Key

European Journal of Taxonomy 427: 1–110 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2018.427 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2018 · Ferrer-Suay M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:47B9B376-F3D2-457C-8F85-6FEFACA1DB11 Palaearctic species of Charipinae (Hymenoptera, Figitidae): two new species, synthesis and identification key Mar FERRER-SUAY 1,*, Jesús SELFA 2 & Juli PUJADE-VILLAR 3 1,2 Universitat de València, Facultat de Ciències Biològiques, Departament de Zoologia. Campus de Burjassot-Paterna, Dr. Moliner 50, 46100 Burjassot (València), Spain. 3 Universitat de Barcelona, Facultat de Biologia, Departament de Biologia Animal, Avda. Diagonal 645, 08028-Barcelona, Spain. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:B7059757-51CD-45DD-A182-C64FA5EF63C8 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:C01B4FA6-6C5C-4DDF-A114-2B06D8FE4D20 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:94C497E0-C6A1-48BD-819D-FE5A8036BECD Abstract. The Charipinae Dalla Torre & Kieffer, 1910 present in the Palaearctic region are revised; 2410 specimens have been identified, belonging to 75 species: 52 to Alloxysta, one to Apocharips, six to Dilyta and 16 to Phaenoglyphis. For 33 species, new country-level distribution records are provided. Two new species are here described: Alloxysta palearctica Ferrer-Suay & Pujade-Villar sp. nov. and Alloxysta pascuali Ferrer-Suay sp. nov. A diagnosis for these species is included and their diagnostic features are shown in different figures. A key to identify all the species of Charipinae in the Palaearctic region is also given. -

(Hemiptera: Liviidae) De Rutáceas En Cazones, Veracruz, México

COLEGIO DE POSTGRADUADOS INSTITUCION DE ENSEÑANZA E INVESTIGACION EN CIENCIAS AGRÍCOLAS CAMPUS MONTECILLO POSTGRADO DE FITOSANIDAD ENTOMOLOGÍA Y ACAROLOGÍA CARACTERIZACIÓN MORFOMÉTRICA Y GENÉTICA DE Diaphorina citri (HEMIPTERA: LIVIIDAE) DE RUTÁCEAS EN CAZONES, VERACRUZ, MÉXICO FLORINDA GARCÍA PÉREZ T E S I S PRESENTADA COMO REQUISITO PARCIAL PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE: DOCTORA EN CIENCIAS MONTECILLO, TEXCOCO, EDO. DE MEXICO 2013 Esta tesis titulada “CARACTERIZACIÓN MORFOMÉTRICA Y GENÉTICA DE Diaphorina citri (HEMIPTERA: LIVIIDAE) DE RUTÁCEAS EN CAZONES, VERACRUZ, MÉXICO”, se realizó bajo la dirección de la Dra. Laura Delia Ortega Arenas, Profesora Investigadora del Colegio de Postgraduados, como parte del Megaproyecto “MANEJO DE LA ENFERMEDAD HUANGLONGBING (HLB) MEDIANTE EL CONTROL DE POBLACIONES DEL VECTOR Diaphorina citri (HEMIPTERA: PSYLLIDAE), EL PSÍLIDO ASIÁTICO DE LOS CÍTRICOS”, bajo la responsabilidad del Dr. José Isabel López Arroyo y con el apoyo financiero FONSEC-SAGARPA-CONACYT con clave 2009-108591. CARACTERIZACIÓN MORFOMÉTRICA Y GENÉTICA DE Diaphorina citri (HEMIPTERA: LIVIIDAE) DE RUTÁCEAS EN CAZONES, VERACRUZ, MÉXICO Florinda García Pérez, Dr. Colegio de Postgraduados, 2013 RESUMEN El psílido asiático de los cítricos, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Liviidae), es una plaga de importancia cuarentenaria por ser un eficiente vector de la bacteria Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, agente causal del Huanglongbing (HLB). Al ser una plaga invasora y de reciente introducción a nuestro país, es posible que el aislamiento geográfico desde su lugar de origen derive en variaciones morfométricas y biológicas que dificulten la definición de una estrategia de manejo. Por lo anterior en este estudio se planteó realizar estudios de morfometría y conocer la diversidad genética de D. citri mediante el uso de una región del marcador genético mitocondrial Citocromo oxidasa subunidad I (COI) en psílidos adultos recolectados en hospedantes rutáceas en la zona citrícola de Cazones, Veracruz. -

The Hemiptera-Sternorrhyncha (Insecta) of Hong Kong, China—An Annotated Inventory Citing Voucher Specimens and Published Records

Zootaxa 2847: 1–122 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) ZOOTAXA 2847 The Hemiptera-Sternorrhyncha (Insecta) of Hong Kong, China—an annotated inventory citing voucher specimens and published records JON H. MARTIN1 & CLIVE S.K. LAU2 1Corresponding author, Department of Entomology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, U.K., e-mail [email protected] 2 Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, Cheung Sha Wan Road Government Offices, 303 Cheung Sha Wan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong, e-mail [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by C. Hodgson: 17 Jan 2011; published: 29 Apr. 2011 JON H. MARTIN & CLIVE S.K. LAU The Hemiptera-Sternorrhyncha (Insecta) of Hong Kong, China—an annotated inventory citing voucher specimens and published records (Zootaxa 2847) 122 pp.; 30 cm. 29 Apr. 2011 ISBN 978-1-86977-705-0 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-706-7 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2011 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2011 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. -

A Revised Classification of the Jumping Plant-Lice (Hemiptera: Psylloidea)

Zootaxa 3509: 1–34 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:16A98DD0-D7C4-4302-A3B7-64C57768A045 A revised classification of the jumping plant-lice (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) DANIEL BURCKHARDT1 & DAVID OUVRARD2 1Naturhistorisches Museum, Augustinergasse 2, CH-4001 Basel, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A revised classification for the world jumping plant-lice (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) is presented comprising all published family and genus-group names. The new classification consists of eight families: Aphalaridae, Carsidaridae, Calophy- idae, Homotomidae, Liviidae, Phacopteronidae, Psyllidae and Triozidae. The Aphalaridae, Liviidae and Psyllidae are redefined, 20 family-group names as well as 28 genus-group names are synonymised, and one replacement name is proposed [Sureaca nomen nov., for Acaerus Loginova, 1976]. Forty two new species combinations are proposed re- sulting from new genus-group synonymies and a replacement name. One subfamily and three genera are considered taxa incertae sedis, and one genus a nomen dubium. Finally eight unavailable names are listed (one family-group and seven genus-group names). Key words: Psyllids, classification, diagnosis, systematics, taxonomy, new taxa, synonymy. Introduction Jumping plant-lice have lately shifted into general awareness as vectors of serious plant diseases, as economically important pests in agriculture and forestry and as potential control organisms of exotic invasive plants. Diaphorina citri Kuwayama which transmits the causal agent of huanglongbing (HLB, greening disease) is considered today the most serious citrus pest in Asia and America (Bonani et al., 2009; de Leon et al., 2011; Tiwari et al., 2011). -

An Annotated Checklist of the Jumping Plant-Lice (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) of Iran

J. Entomol. Res. Soc., 18(1): 37-55, 2016 ISSN:1302-0250 An Annotated Checklist of the Jumping Plant-lice (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) of Iran Ahmad ZENDEDEL1 Daniel BURCKHARDT2 Lida FEKRAT3 Shahab MANZARI4 Hussein Sadeghi NAMAGHI5 1,3,5Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, IRAN 2Naturhistorisches Museum, Augustinergasse 2, CH-4001 Basel, SWITZERLAND 4Insect Taxonomy Research Department, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Tehran, IRAN. e-mails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT A revised checklist to the species of Psylloidea (Hemiptera) from Iran is presented based mainly on literature records, along with some new information on host plant data, distribution and natural enemies. The list includes 95 identified species 26 genera of 5 families, of which one species,Cacopsylla ambigua (Foerster), is newly recorded for the Iranian fauna and five species are only provisionally identified. Another eight species have been listed for Iran that are identified only to genus. The families Aphalaridae and Homotomidae with 27 and 2 species are the most and the least species-rich families, respectively. The predatory mite Erythraeus (E.) garmasaricus Saboori et al. (Acarina: Trombidiformes: Erythraeidae) is reported for the first time from psyllids. Key words: Palaearctic, distribution, biogeography, host plant, psyllids, pest species, natural enemies. INTRODUCTION Psyllids or jumping plant-lice with about 3800 described species worldwide, are highly host-specific phloem-feeding insects, in particular as immatures (Burckhardt,et al., 2014). -

FDACS DPI Tri-Ology Volume 51, Number 1, January - February 2012

FDACS DPI Tri-ology Volume 51, Number 1, January - February 2012 DACS-P-00124 Volume 51, Number 1, January - February 2012 Printer-Friendly PDF Version DPI's Bureau of Entomology, Nematology and Plant Pathology (the botany section is included in this bureau) produces TRI-OLOGY six times a year, covering two months of activity in each issue. The report includes detection activities from nursery plant inspections, routine and emergency program surveys, and requests for identification of plants and pests from the public. Samples are also occasionally sent from other states or countries for identification or diagnosis. Highlights Following are a few of the notable entries from this volume of TRI-OLOGY. These entries Section Reports are reports of interesting plants or unusual pests, some of which may be problematic. See Section Reports for complete information. Botany Neophyllaphis sp. nr. fransseni, a Entomology podocarpus aphid, a probable Western Nematology Hemisphere record. In Florida, we are accustomed to aphids on the new growth of Plant Pathology Podocarpus species. Division of Plant Industry, plant inspector Scott D. Krueger noticed aphids Our Mission…getting it done of a different color. Instead of the dusty blue aphids we usually see, he noticed that they The mission of the Division of were yellow, red and purple. Upon closer Neophyllaphis sp. nr. fransseni, Plant Industry is to protect a podocarpus aphid, close view examination, we determined that these aphids Photograph courtesy of Lyle J. Florida’s native and are not Neophyllaphis podocarpi, the species Buss, University of Florida commercially grown plants and that has been in Florida for a long time.