Buckhead Heritage Oral History Project, Robert Foreman.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Matters Most for a Happy and Successful Marriage Advice for Newly Weds

What Matters Most For A Happy and Successful Marriage Advice for Newly Weds Compiled by Rev. Katherine S. Blackburn, M.Div What Matters Most For A Happy and Successful Marriage Advice for Newly Weds Compiled by Rev. Katherine S. Blackburn, M.Div Acknowledgments I am deeply humbled at the bounty that has flowed into my life since the writing of this booklet and the Master of Divinity thesis. First of all, I want to thank the twenty couples who graciously granted me an interview. The honest and intimate sharing of your marital experience for twenty years or more touched my heart and soul. With the couples who agreed to pre-marital counseling, I am grateful. Your interest and willingness to practice the techniques gave me perseverance as I realized this work is important and significant for newly weds. The booklet would not have been created without the group of grad school advisors and teachers. Their genuine support and caring in addition to continuous nudges to finish kept me returning to the task. I appreciate the authors, therapists, and friends who shared their professional skills and writings for the project. Most important, I feel fortunate to have the nurturing and dependable love of my husband Regi who agreed to try new ideas for a better marriage. In fact, on our first date, to resolve our first disagreement, he said, “Meet me half-way.” Thus began a foundation built on cooperation and trust. It is the basis for this booklet. Dear Readers, Congratulations! You are married and on your way to a happy and fulfilling life as committed partners. -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

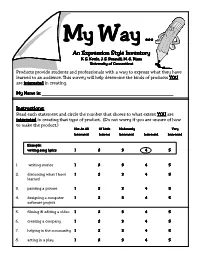

An Expression Style Inventory K

MMMyy WWWayay ...... An Expression Style Inventory K. E. Kettle, J. S. Renzulli, M. G. Rizza University of Connecticut Products provide students and professionals with a way to express what they have learned to an audience. This survey will help determine the kinds of products YOU are interested in creating. My Name is: ___________________________________________________________________ Instructions: Read each statement and circle the number that shows to what extent YOU are interested in creating that type of product. (Do not worry if you are unsure of how to make the product.) Not At All Of Little Moderately Very Interested Interest Interested Interested Interested Example: writing song lyrics 1 2 3 4 5 1. writing stories 1 2 3 4 5 2. discussing what I have 1 2 3 4 5 learned 3. painting a picture 1 2 3 4 5 4. designing a computer 1 2 3 4 5 software project 5. filming & editing a video 1 2 3 4 5 6. creating a company 1 2 3 4 5 7. helping in the community 1 2 3 4 5 8. acting in a play 1 2 3 4 5 MMyy WWayay ...... An Expression Style Inventory Not At All Of Little Moderately Very Interested Interest Interested Interested Interested 9. building an invention 1 2 3 4 5 10. playing a musical 1 2 3 4 5 instrument 11. writing for a newspaper 1 2 3 4 5 12. discussing ideas 1 2 3 4 5 13. drawing pictures for 1 2 3 4 5 a book 14. designing an interactive 1 2 3 4 5 computer project 15. -

Getting to Know Georgia

Getting to Know Ge rgia A Guide for Exploring Georgia’s History and Government Published by the Office of Secretary of State Brian P. Kemp Information in this guide updated June 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 HISTORICAL INFORMATION THE HISTORY OF GEORGIA AND ITS CAPITAL CITIES 1 HISTORY OF ATLANTA 5 PART 2 STATE GOVERNMENT GEORGIA GOVERNMENT 10 FINDING ELECTED OFFICIALS 12 VOTER REGISTRATION/STATEWIDE ELECTION INFORMATION 12 LEGISLATIVE SEARCH INFORMATION 12 GEORGIA STUDENT PAGE PROGRAM 12 HOW A BILL BECOMES A LAW 13 CHARTS HOW A BILL IS PASSED IN THE GEORGIA LEGISLATURE CHART GEORGIA ELECTORATE CHART PART 3 STATE WEB SITES, SYMBOLS AND FACTS GEORGIA WEB SITES 15 STATE SYMBOLS 16 STATE SONG 20 GEORGIA FAST FACTS 21 TIMELINE AND MAP OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENTS TIMELINE GEORGIA COUNTIES MAP PART 4 TOURING THE CAPITOL FIELD TRIP GUIDE FOR TEACHERS 22 THE GEORGIA CAPITOL MUSEUM AND HALL OF VALOR 26 CAPITOL GROUNDS 27 DIRECTIONS TO CAPITOL EDUCATION CENTER 29 MAP CAPITOL AREA MAP 1 Historical Information The History of Georgia and Its Capital Cities SAVANNAH On June 9, 1732, King George II signed the charter granting General James Edward Oglethorpe and a group of trustees permission to establish a thirteenth British colony to be named in honor of the King. The motives for the grant were to aid worthy poor in England, to strengthen the colonies, increase imperial trade and navigation, and to provide a buffer for Carolina against Spanish Florida. Even though the King had granted the charter for the colony, Oglethorpe wanted to get the consent of the Indians inhabiting the area. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Frank's World

Chris Rojek / Frank Sinatra Final Proof 9.7.2004 10:22pm page 7 one FRANK’S WORLD Frank Sinatra was a World War One baby, born in 1915.1 He became a popular music phenomenon during the Second World War. By his own account, audiences adopted and idol- ized him then not merely as an innovative and accomplished vocalist – his first popular sobriquet was ‘‘the Voice’’ – but also as an appealing symbolic surrogate for American troops fighting abroad. In the late 1940s his career suffered a precipitous de- cline. There were four reasons for this. First, the public perception of Sinatra as a family man devoted to his wife, Nancy, and their children, Nancy, Frank Jr and Tina, was tarnished by his high-octane affair with the film star Ava Gardner. The public face of callow charm and steadfast moral virtue that Sinatra and his publicist George Evans concocted during his elevation to celebrity was damaged by his admitted adultery. Sinatra’s reputation for possessing a violent temper – he punched the gossip columnist Lee Mortimer at Ciro’s night- club2 and took to throwing tantrums and hurling abuse at other reporters when the line of questioning took a turn he disap- proved of – became a public issue at this time. Second, servicemen were understandably resentful of Sina- tra’s celebrity status. They regarded it as having been easily achieved while they fought, and their comrades died, overseas. Some members of the media stirred the pot by insinuating that Sinatra pulled strings to avoid the draft. During the war, like most entertainers, Sinatra made a virtue of his patriotism in his stage act and music/film output. -

The Lighter Side

rily on his own. He was, in most cases, PEGGY LEE: Natural Woman. Peggy trapped in dance band tempos and was Lee, vocals; Mike Melvoin and Bobby only beginning to discover the uses of Bryant, arr. and cond. (Everyday Peo- the microphone. ple; Lean On Me; Please Send Me Otherwise, in listening to Powell versus Someone to Love; eight more.) Capitol Sinatra, one finds that movie songs ST 183, $4.98. in the Thirties were just as ghastly as Peggy Lee can work with any vocal movie songs in the Forties, but Powell fashion and flatter it without betraying got slightly better material than Sinatra. herself. What other white singer, for In general, Powell's backing is superior instance, can get into Ray Charles' to Sinatra's simply because it is looser. material on his terms as well as her The Sinatra disc starts out with three own? The question, in relation to chang- selections recorded during J. Caesar ing trends, is what kind of singer does Petrillo's great contribution to American Miss Lee feel like being? I was won - culture (the two -year ban on instrumen- the dering if she would care to interpret tal recording during World War H): the latest fashion, and if so, how she here Sinatra is accompanied by several would define it. Now we know. girls going dooby- dooby -doo. Dismal. lighter As usual, Miss Lee takes over once After that, some of Axel Stordahl's back- she decides to, singing market hits ings suggest a Tommy Dorsey setting, with more natural instinct than any but the studio strings become stickily other of our classic pop singers. -

THE SOCIAL and CIVIC IMPACTS of ROBERT WINSHIP WOODRUFF in the CITY of ATLANTA DURING the 1960S

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2007 The oS cial and Civic Impacts of Robert Winship Woodruff in the itC y of Atlanta During the 1960s Andrew Land Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Land, Andrew, "The ocS ial and Civic Impacts of Robert Winship Woodruff in the itC y of Atlanta During the 1960s" (2007). All Theses. 103. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/103 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOCIAL AND CIVIC IMPACTS OF ROBERT WINSHIP WOODRUFF IN THE CITY OF ATLANTA DURING THE 1960s A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Andrew Cromer Land May 2007 Accepted by: Dr. H. Roger Grant, Committee Chair Dr. Jerome V. Reel, Jr. Dr. Paul C. Anderson ABSTRACT Robert Winship Woodruff was born December 6, 1889, and died March 7, 1985. For more than sixty‐two years he headed the Coca‐Cola Company, headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia. Woodruff amassed a tremendous fortune and was for years the richest man in Georgia and one of the wealthiest in the South. His wealth made him extremely powerful in political circles, and he came to dominate the city of Atlanta in a way unlike any other private citizen in any other comparable American city of the time. -

DOWNTOWN News for Central Atlanta Progress Members and Downtown Property Owners

FALL 2010 WHAT’S UP DOWNTOWN News for Central Atlanta Progress members and Downtown property owners. Atlanta Streets Alive in Woodruff Park Returning in October. See Page 12. Fall 2010 n E W S Georgia Forward Forum Internship Program Explores Georgia’s Future Honors Paul Kelman n Aug. 25, Georgia’s academic, civic, economic, n honor of Paul B. Kelman’s 22 years of leadership at Central Atlanta and government leaders began a long-awaited Progress, the organization has renamed the existing internship program the Kelman Internship Program. During Kelman’s tenure, major changes conversation about the future of our state. The occurred in the landscape of Downtown Atlanta. Most notable is the Macon State College Conference Center played creation of ADID in 1995, which funds the Ambassador Force, a highly visible Ohost to the 2010 Georgia Forward Forum. More than 200 authoritative presence on Downtown. stakeholders, representing every corner of the state, convened A Florida native, Kelman received his civil engineering degree from Georgia to discuss the most pressing challenges facing Georgians Tech and masters degrees from the University of Illinois (in urban planning) today, including the economy, water equity, education, and and Georgia State University (in public administration). He received the transportation. Owens-Illinois Scholarship at Georgia Tech and the Richard King Mellon Fellowship at the University of Illinois. Kelman is past president of the Georgia Following the theme “Together, improving Planning Association and a charter member of the American Planning the state of our state,” the day-long forum Association. In April 2003, he received the first Jack F. -

CITY of ATLANTA Roosevelt Council, Jr

KEISHA LANCE BOTTOMS CITY OF ATLANTA Roosevelt Council, Jr. MAYOR CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER [email protected] DEPARTMENT OF FINANC E OFFICE OF THE CFO INTEROFFICE MEMORANDUM TO: ATLANTA CITY COUNCIL FROM: ROOSEVELT COUNCIL, JR. SUBJECT: WESTSIDE TAD/GULCH DEVELOPMENT DATE: SEPTEMBER 7, 2018 Please find the attached summary documents related to key legislative papers originally introduced on August 6, 2018. These summaries provide a general overview of the salient terms that form the foundation of the proposed partnership between the City, Invest Atlanta and CIM with regards to the development of the Gulch. All relevant documents memorializing the terms of the proposed Westside Tax Allocation District extension, the proposed Gulch Development Project and other related matters will be uploaded to the Electronic Legislative Management System (“ELMS”) for your review. Consistent with the Mayor’s sustainability “best practices,” we have elected not to print out these voluminous documents. However, if you desire hard copies, please let us know. Please know that we are also available to discuss the details of these documents with you. Please do not hesitate to give me a call. 1 ASSET SWAP SUMMARY In December 2017, Ordinance 17-O-1793 was approved, authorizing the City of Atlanta (“City”) to exchange certain real property with CIM Spring St. (Atlanta) Owner, LLC (“CIM”). In August 2018, Ordinance 18-O-1484 was introduced to add additional real property (160 Trinity Ave.) from CIM. City of Atlanta Receives. CIM will contribute the following assets to the City of Atlanta: 1) 175 Spring Street (Demolished with resurfaced Parking Lot) – An existing building that will be demolished leaving a clean, paved land site that can be used for parking totaling approximately 15,500 SF. -

Early History of Atlanta in Medicine, Architecture, Opera, Etc

EARLY HISTORY OF ATLANTA in MEDICINE EARLY HISTORY OF MEDICINE IN ATLANTA* By Frank K. Boland, M.D. From the opening chapter of "Makers of Atlanta Medicine," a series of articles written by Dr. J. L. Campbell for The Bulletin of the Fulton County Medical Society in 1929, we are informed that the first physician to locate in the territory now known as Fulton county was Dr. William Gilbert, grandfather of Dr. W. L. Gilbert, former county commissioner, and at present a member of the Fulton County Medical Society. The elder Gilbert moved from South Carolina about 1829 and settled on the Campbellton road, to serve the thinly populated sections around old Utoy, Mount Gilead and Mount Zion churches. Just before the War between the States he moved to Atlanta and formed a partnership with his brother, Dr. Joshua Gilbert. In Martin's Atlanta and Its Builders, Dr. Joshua Gilbert is named by Dr. George Smith as Atlanta's first physician, who located here in 1845. It is interesting to note that Doctor Gilbert and Crawford W. Long, the discoverer of anesthesia, were born in the same year, 1815, and that Doctor Long was a resident of Atlanta in the early part of the 1850 decade, during which time he bought the lot bounded on three sides by Peachtree, Luckie, and Forsyth streets and began the erection of a fine residence. Abruptly deciding to move to Athens, where his children would have better educational advantages, he sold his incompleted building to Judge Clark Howell in 1855, and left the town with one medical man the less. -

Off-Beats and Cross Streets: a Collection of Writing About Music, Relationships, and New York City

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Stonecoast MFA Student Scholarship 2020 Off-Beats and Cross Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City Tyler Scott Margid University of Southern Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast Recommended Citation Margid, Tyler Scott, "Off-Beats and Cross Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City" (2020). Stonecoast MFA. 135. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast/135 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stonecoast MFA by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Off-Beats and Cross-Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUTREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE, STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITINC BY Tyler Scott Margid 20t9 THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITING November 20,2019 We hereby recommend that the thesis of Tyler Margid entitled OffÙeats and Cross- Streets be accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Advisor Florio -'1 4rl:ri'{" ¡ 'l¡ ¡-tÁ+ -- Reader Debra Marquart Director J Accepted ¿/k Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Adam-Max Tuchinsky At¡stract Through a series of concert reviews, album reviews, and personal essays, this thesis tracks a musical memoir about the transition from a childhood growing up in a sheltered Connecticut suburb to young adulthood working in New York City, discovering relationships and music scenes that shape the narrator's senss of identity as well the larger culture he f,rnds himself in.