200617 WBH Final Kopie New Font.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebooks for Kobo & Other E-Ink Ereaders Using Adobe Digital

eBooks for Kobo & other E-ink eReaders using Adobe Digital Editions 4.5+ Prince George Public Library – www.pgpl.ca March 2017 (JFE) For additional help, please go to help.overdrive.com This guide will explain the steps needed to set up your eReader, find and check out eBooks using our Library2Go service, then download them on your computer and transfer them to your eReader. Download, install and setup Adobe Digital Editions on your computer 1. On your computer open your web browser and go to www.pgpl.ca Click on Download eBooks & More and then click on Library2Go. 2. On the Library2Go website, click the Help icon near the top right of your screen Click the Applications link Click the Adobe Digital Editions link, this will open a new window to adobe.com 3. On the Adobe download site: From the menu at the top of your screen, click Download Under 'Adobe Digital Editions 4.5 Installers,' click the Windows or Mac link to download the installer Once the download is complete, open and run the installer file The 'Setup' window opens. Review and accept the license agreement then click Next to continue Select the options you prefer then click Next. Make sure to uncheck ‘agree’ to any non-Adobe additional offers Confirm the download location then click Next Click Done to exit the setup and launch Adobe Digital Editions (ADE) Authorize Adobe Digital Editions with an Adobe ID This must be done to be able to read the eBook on your computer and device When Adobe Digital Editions opens for the first time click Help then Authorize Computer To use eBooks from the library, you must authorize your computer with an Adobe ID. -

What Matters Most for a Happy and Successful Marriage Advice for Newly Weds

What Matters Most For A Happy and Successful Marriage Advice for Newly Weds Compiled by Rev. Katherine S. Blackburn, M.Div What Matters Most For A Happy and Successful Marriage Advice for Newly Weds Compiled by Rev. Katherine S. Blackburn, M.Div Acknowledgments I am deeply humbled at the bounty that has flowed into my life since the writing of this booklet and the Master of Divinity thesis. First of all, I want to thank the twenty couples who graciously granted me an interview. The honest and intimate sharing of your marital experience for twenty years or more touched my heart and soul. With the couples who agreed to pre-marital counseling, I am grateful. Your interest and willingness to practice the techniques gave me perseverance as I realized this work is important and significant for newly weds. The booklet would not have been created without the group of grad school advisors and teachers. Their genuine support and caring in addition to continuous nudges to finish kept me returning to the task. I appreciate the authors, therapists, and friends who shared their professional skills and writings for the project. Most important, I feel fortunate to have the nurturing and dependable love of my husband Regi who agreed to try new ideas for a better marriage. In fact, on our first date, to resolve our first disagreement, he said, “Meet me half-way.” Thus began a foundation built on cooperation and trust. It is the basis for this booklet. Dear Readers, Congratulations! You are married and on your way to a happy and fulfilling life as committed partners. -

The New Atlantis Sir Francis Bacon

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The New Atlantis, by Sir Francis Bacon The Project Gutenberg eBook of The New Atlantis, by Sir Francis Bacon Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The New Atlantis Author: Sir Francis Bacon Release Date: December, 2000 [EBook #2434] [This HTML file was first posted on June 11, 2003] Edition: 11 Language: English Character set encoding: utf-8 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, THE NEW ATLANTIS *** http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext00/nwatl11h.htm (1 of 33)04-03-2006 19:06:18 The Project Gutenberg eBook of The New Atlantis, by Sir Francis Bacon Revision to edition 11 and preparation of HTML version by William Fishburne The New Atlantis By Sir Francis Bacon INTRODUCTORY NOTE Bacon's literary executor, Dr. -

Sex Object’ Offers by BEN SCHMITZ Duction of a Brash, Overdriven TER’S” Sonic Build

PAGE 8 / campustimes.org MONDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2016 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT Bon Iver Drops ‘22, A Million’ ‘Sex Object’ Offers BY BEN SCHMITZ duction of a brash, overdriven TER’s” sonic build. Truth, Reality in CONTRIBUTING WRITER drum groove and choppy vocal Closing the album, “00000 samples about halfway through. Million” brings back the folk- Upon the release of his sopho- The last few lines of the lyrics like songwriting of “29 #Straf- Feminism, Life more self-titled release, Bon Iv- profess a desire and motivation ford APTS” and closes the al- er’s Justin Vernon made it abun- in Vernon to move on from his bum’s lyrical themes powerfully. BY ISABEL DRUKKER “The Baby”) and creating an dantly clear that he is a master demons, with him singing, “I The line, “If it’s harmed, it’s A&E EDITOR aesthetic (“Subways,” “Grilled of balancing between too radi- could go forward in the light, harmed me, it’ll harm, I let Cheese,” “Ice”). But if there is a cal and not different enough. well, I better fold my clothes.” it in,” is a clear final word on Jessica Valenti’s first memoir, consistent aesthetic of the mem- Typically, when an artist finds “22, A Million’s” is the best Vernon’s acceptance of the de- “Sex Object” (2016), says a lot. oir, I have yet to see it. success in a given style, they And it should come to no But I don’t think this is a fault. continue their body of work in surprise that the founder of the Valenti’s memoir reads as a a way that is cohesive and non- award-winning site Feminist- tale of transformation and the alienating to their newfound ing and regular columnist for idea that no person has to be, or fan base. -

BEACH BOYS Vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music

The final word on the Beach Boys versus Beatles debate, neglect of American acts under the British Invasion, and more controversial critique on your favorite Sixties acts, with a Foreword by Fred Vail, legendary Beach Boys advance man and co-manager. BEACH BOYS vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music Buy The Complete Version of This Book at Booklocker.com: http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/3210.html?s=pdf BEACH BOYS vs Beatlemania: Rediscovering Sixties Music by G A De Forest Copyright © 2007 G A De Forest ISBN-13 978-1-60145-317-4 ISBN-10 1-60145-317-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2007 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY FRED VAIL ............................................... XI PREFACE..............................................................................XVII AUTHOR'S NOTE ................................................................ XIX 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD 1 2. CATCHING A WAVE 14 3. TWIST’N’SURF! FOLK’N’SOUL! 98 4: “WE LOVE YOU BEATLES, OH YES WE DO!” 134 5. ENGLAND SWINGS 215 6. SURFIN' US/K 260 7: PET SOUNDS rebounds from RUBBER SOUL — gunned down by REVOLVER 313 8: SGT PEPPERS & THE LOST SMILE 338 9: OLD SURFERS NEVER DIE, THEY JUST FADE AWAY 360 10: IF WE SING IN A VACUUM CAN YOU HEAR US? 378 AFTERWORD .........................................................................405 APPENDIX: BEACH BOYS HIT ALBUMS (1962-1970) ...411 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................419 ix 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD Rock is a fickle mistress. -

Italian Actress Virna Lisi Dead at 78

Lifestyle FRIDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2014 Italian actress Virna Lisi dead at 78 talian actress Virna Lisi, who played opposite Hollywood stars including Frank Sinatra in the 1960s Iand later established herself an acclaimed character actress, has died at the age of 78. Italian media quoted her son as saying that Lisi had passed away peacefully in her sleep on Wednesday, a month after being diagnosed Philippine crime lord with an incurable illness. Born in Ancona in 1936, she was an established cine- ma and theatre actress before Hollywood producers enjoys jailhouse rock looking for a new Marilyn Monroe came rime lord “Herbert C” was enjoying chart success. In one of many clips about calling in the mid- national fame and growing iTunes his career posted on YouTube and other 1960s.With Jack Csuccess after reinventing himself as social media, Colanggo appears at a Lemmon she made a lovelorn balladeer from inside the concert in the Bilibid gymnasium where “How to Murder Your Philippines’ biggest jail-until police cut he accepts an Ivory “platinum” record Wife” in 1965 and fol- In this file picture taken on May 23, 1994 US film short his career. Herbert Colanggo lost his award for selling 15,000 albums. He also lowed up by starring director Quentin Tarantino poses with the Golden recording studio and other bribe-induced celebrates being voted “best new male alongside Tony Curtis in Palm he was awarded for his film “Pulp Fiction”, musical privileges after a raid on the recording artist” by a group of entertain- “Not with my Wife, You next to Italian actress Virna Lisi who was named secret prison villas kept by 20 of the ment journalists this year, an accolade Don’t” and with Sinatra best actress for her part in the French movie “La nation’s most notorious robbery, kidnap- that garnered mainstream media cover- in “Assault on a Queen” ping and drug kingpins. -

303.893.4234 Davidbsmithgallery.Com I First Exhibited Gregory Euclide at the David B

GREGORY EUCLIDE 1543 A Wazee Street Denver, CO 80202 tel: 303.893.4234 davidbsmithgallery.com I first exhibited Gregory Euclide at the David B. Smith Gallery in our inaugural exhibition in February, 2007. Since that time, I have been fortunate to work closely with Gregory, and observe his creative process firsthand. He has attracted attention for his complex installations, unusual dioramas, and intricate and surprising sculptures. His ideas concerning the landscape — the conflict between the real and the ideal, and between pristine nature and the inevitable impact of an inhabited world — are executed with vision and perspective. What makes Euclide’s work so attractive and so compelling is the way he uses both paint and multiple media to express his ideas. His painting is impressive — detailed and executed with great skill. But it is the way he integrates this work into unique and intriguing relief pieces that particularly challenges the viewer to engage in a dialogue about the work. Through an unusually creative use of both natural and synthetic materials, Euclide transports his viewers into the world that he has created. He examines the culture in which we live, questioning how we can simultaneously preserve the environment while maintaining the benefits of a modern lifestyle. Euclide’s world is an extension of his early experiences outdoors, time spent both alone and with his family. He developed an extraordinary ability to observe and create, to evolve his ideas on location, and bring back remnants of organic treasures and weathered waste to use in his works. He is an artist who thrives in nature, and carries his love back into the studio where he puts his thoughts to paper to make landscape art fresh and engaging. -

Bon Iver Holocene Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bon Iver Holocene mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Folk, World, & Country Album: Holocene Country: US Released: 2011 Style: Folk Rock, Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1736 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1680 mb WMA version RAR size: 1122 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 736 Other Formats: AHX DXD MPC DTS WAV VOX VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Holocene Alto Saxophone, Clarinet [Clarinets] – Colin StetsonGuitar [High Strung Guitar], Guitar [Guitars], Baritone Guitar, Synth, Drums, Cymbal [Cymbals], Voice – Justin VernonSnare [Snare Drums], Percussion [Brushes], Bass Drum, Other [Thighs], Handclaps, Other A 5:37 [Granular Synthesis], Synth – Matt McCaughanTenor Saxophone [Tenor Saxophones], Soprano Saxophone [Soprano Saxophones] – Mike Lewis*Trumpet [Pedal Trumpets], French Horn [French Horns] – C. J. CamerieriVibraphone, Vibraphone [Bowed Vibraphone] – Sean Carey Voice – Mike NoyceWritten-By – Justin Vernon Come Talk To Me B Drums – Sean Carey Performer [All Other] – Justin VernonVoice – Kimberly Lockwood, Rick 6:57 LockwoodWritten-By – Peter Gabriel Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Jagjaguwar Phonographic Copyright (p) – Jagjaguwar Published By – April Base Publishing Published By – Pentagon Lipservices Published By – Real World Music Ltd. Lacquer Cut At – Sterling Sound Credits Artwork – Gregory Euclide Lacquer Cut By – Ray Janos Notes © & ℗ 2011 Jagjaguwar Side A: © 2011 April Base Publishing (ASCAP) Side B: © 1992 Pentagon Lipservices/Real World Music Ltd. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 656605221113 Barcode (Printed): -

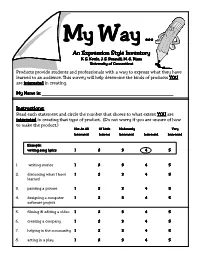

An Expression Style Inventory K

MMMyy WWWayay ...... An Expression Style Inventory K. E. Kettle, J. S. Renzulli, M. G. Rizza University of Connecticut Products provide students and professionals with a way to express what they have learned to an audience. This survey will help determine the kinds of products YOU are interested in creating. My Name is: ___________________________________________________________________ Instructions: Read each statement and circle the number that shows to what extent YOU are interested in creating that type of product. (Do not worry if you are unsure of how to make the product.) Not At All Of Little Moderately Very Interested Interest Interested Interested Interested Example: writing song lyrics 1 2 3 4 5 1. writing stories 1 2 3 4 5 2. discussing what I have 1 2 3 4 5 learned 3. painting a picture 1 2 3 4 5 4. designing a computer 1 2 3 4 5 software project 5. filming & editing a video 1 2 3 4 5 6. creating a company 1 2 3 4 5 7. helping in the community 1 2 3 4 5 8. acting in a play 1 2 3 4 5 MMyy WWayay ...... An Expression Style Inventory Not At All Of Little Moderately Very Interested Interest Interested Interested Interested 9. building an invention 1 2 3 4 5 10. playing a musical 1 2 3 4 5 instrument 11. writing for a newspaper 1 2 3 4 5 12. discussing ideas 1 2 3 4 5 13. drawing pictures for 1 2 3 4 5 a book 14. designing an interactive 1 2 3 4 5 computer project 15. -

Dessa & Jocelyn Hagen

Look Out Above Dessa & Jocelyn Hagen pdf download $1.50 GP-D026 printed $3.00 SATB, a cappella COLLABORATION Dessa & Jocelyn Hagen Look Out Above for a cappella SATB choir, soloists, body percussion, opt. movement Commissioned by & dedicated to the Macalester College Choirs with special thanks to Dr. Michael McGaghie, conductor www.graphitepublishing.com GP-D026 Commissioned by & Dedicated to the Macalester College Choirs pdf download $1.50 with special thanks to Dr. Michael McGaghie, conductor (2017) Look Out Above for SATB a cappella choir, soloists, body percussion & optional movement Text: IPA Guide: We can’t be stopped [ɑ] - car they can’t catch us - sitting just like midnight on the clock: [ɪ] Text by: Dessa Dessa & Jocelyn Hagen it’s all hands up-- [ʌ] - cup, luck with help from the Macalester College Choir Students before tick goes toc, [ɔ] - call, saw it’s just the dust we kick up, so - boat [o] INSTRUCTIONS: Resembling a clock, conductor sweeps look out, look out, look out [u] - who left arm from left to right, like the arm of a clock. Choir look out above members create their ticking sound loudest when the arm cause we’re coming up is directly pointed at them. There should be gradual overlap look about above between sections. there’s no stopping us We can’t be stopped…. Presto = 166-170 q - Dessa pwhispering: P Left 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ã 4 Ó ∑ ∑ Ó From the Composers: tI tI tI tI tI tI tI-kʌ-tI-kʌ-tI-kʌ-tI-kʌ - tI-kʌ-tI - kʌ whispering: p P Some vocal works ask to be delivered by a perfect blend of instructions for its performance, but I am asking you to Middle 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ voices: a finely tuned, powerful, unified sound. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

God Made You to Imagine. BOTTOM LINE

MEMORY VERSE MEMORY VERSE “How you made me is amazing and wonderful. “How you made me is amazing and wonderful. I praise you for that.” I praise you for that.” Psalm 139:14, NIrV Psalm 139:14, NIrV WEEK Creation Story WEEK Creation Story 1 Part 1 1 Part 1 Genesis 1:1-25 Genesis 1:1-25 BOTTOM LINE: BOTTOM LINE: God made everything. God made everything. WEEK Creation Story WEEK Creation Story 2 Part 2: Adam & Eve 2 Part 2: Adam & Eve Genesis 1:26–2:1-25 Genesis 1:26–2:1-25 BOTTOM LINE: BOTTOM LINE: God made you. God made you. WEEK Adam’s First Job WEEK Adam’s First Job 3 Genesis 2:19-20 3 Genesis 2:19-20 BOTTOM LINE: BOTTOM LINE: God made you to imagine. God made you to imagine. WEEK The Fall WEEK The Fall 4 Genesis 3 4 Genesis 3 BOTTOM LINE: BOTTOM LINE: God made you to know Him. God made you to know Him. MORNING TIME MORNING TIME Sometimes it’s diffcult to recognize the Sometimes it’s diffcult to recognize the unique qualities God has given us. Help unique qualities God has given us. Help your child better understand his or her your child better understand his or her amazing qualities by highlighting one each amazing qualities by highlighting one each week and writing it on their bathroom week and writing it on their bathroom mirror. As opportunities arise throughout mirror. As opportunities arise throughout the week, give them examples of the ways the week, give them examples of the ways you’ve seen these qualities shine through you’ve seen these qualities shine through them, and remind them that God loves them, and remind them that God loves watching them make the most of the gifts watching them make the most of the gifts He designed specifcally for them.