Iris Tenuis S Wats., a New Transfer to the Subsection Evansia Lee W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGS Seed List No 69 2020

Seed list No 69 2020-21 Garden Collected Seed 1001 Abelia floribunda 1057 Agrostemma githago 1002 Abies koreana 1058 Albuca canadensis (L. -

Karyological Studies on Iris Japonica Thunb. and Its Allies1) 2) by K

180 Cytologia 10 Karyological Studies on Iris japonica Thunb. and Its Allies1) 2) By K. Yasui Tokyo Imperial University (With 8 text figures) Receic ed MTV 28, 1939 Introduction There are several karyological investigations on Iris japonica. KAZAO (1928) considered the sporophyte of this species as an auto triploid having 54 chromosomes. But SIMONET (1932, 1934) re ported I. japonica as a diploid plant with 34 chromosomes in its root-tip cells, and considered I. japonica var aphrodite as a hyper triploid and interpreted the chromosome constitution as 2n=51+3, the latter 3 chromosomes being considered as derived from 3 of 51 chromosomes in I. japonica by fragmentation which occurred att their median constrictions. The karyological investigation in I. japonica and the other 2 allied species, which were kindly put at my deposal by Dr. S. IMA MURA of Kyoto Imp. University, gave me some results different from those of the previous authors as is described below. Material and Method In the fixing of the root-tip cells both NAVASHIN's and LEWITSKY's solutions were used. When fixed in the latter, the chromosomes were found longer and slender than when fixed in the former solution, but there was no essential difference in the distribu tion of chromosomes in the equatorial plate. NEWTON'S gentian violet staining was generally adopted. Materials for the study of meiosis were fixed mostly with NAVASHIN'S fluid and stained with HEIDENHAIN'S iron-alum haematoxylin. Acetocarmine smears were also tried in the study of the pollen mother cells. Drawings were made with a camera lucida. -

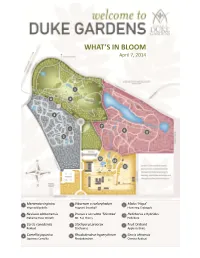

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

These De Doctorat De L'universite Paris-Saclay

NNT : 2016SACLS250 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de doctorat (Biologie) Par Mlle Nour Abdel Samad Titre de la thèse (CARACTERISATION GENETIQUE DU GENRE IRIS EVOLUANT DANS LA MEDITERRANEE ORIENTALE) Thèse présentée et soutenue à « Beyrouth », le « 21/09/2016 » : Composition du Jury : M., Tohmé, Georges CNRS (Liban) Président Mme, Garnatje, Teresa Institut Botànic de Barcelona (Espagne) Rapporteur M., Bacchetta, Gianluigi Università degli Studi di Cagliari (Italie) Rapporteur Mme, Nadot, Sophie Université Paris-Sud (France) Examinateur Mlle, El Chamy, Laure Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Examinateur Mme, Siljak-Yakovlev, Sonja Université Paris-Sud (France) Directeur de thèse Mme, Bou Dagher-Kharrat, Magda Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Co-directeur de thèse UNIVERSITE SAINT-JOSEPH FACULTE DES SCIENCES THESE DE DOCTORAT DISCIPLINE : Sciences de la vie SPÉCIALITÉ : Biologie de la conservation Sujet de la thèse : Caractérisation génétique du genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Présentée par : Nour ABDEL SAMAD Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR ÈS SCIENCES Soutenue le 21/09/2016 Devant le jury composé de : Dr. Georges TOHME Président Dr. Teresa GARNATJE Rapporteur Dr. Gianluigi BACCHETTA Rapporteur Dr. Sophie NADOT Examinateur Dr. Laure EL CHAMY Examinateur Dr. Sonja SILJAK-YAKOVLEV Directeur de thèse Dr. Magda BOU DAGHER KHARRAT Directeur de thèse Titre : Caractérisation Génétique du Genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Mots clés : Iris, Oncocyclus, région Est-Méditerranéenne, relations phylogénétiques, status taxonomique. Résumé : Le genre Iris appartient à la famille des L’approche scientifique est basée sur de nombreux Iridacées, il comprend plus de 280 espèces distribuées outils moléculaires et génétiques tels que : l’analyse de à travers l’hémisphère Nord. -

Four New Early Spring-Flowering Evergreen Iris Cultivars

CULTIVAR AND GERMPLASM RELEASES HORTSCIENCE 55(1):103–105. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI14433-19 Dawn’ (‘Xiaodie’), ‘Butterflies in Bloom’ (‘Huadie’), and ‘Butterfly Veil’ (‘Dieyi’) by Four New Early Spring-flowering the American Iris Society in 2019. Evergreen Iris Cultivars Description Feng-yang Yu and Yue-e Xiao The selection process was conducted at the Conservation Nursery of the Shanghai Research Center, Shanghai Botanical Garden, Shanghai, 200231, China; Botanical Garden in Shanghai, China. For and Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Sustainable Plant Innovation, each of the four new cultivars, 30 clones were Shanghai 200231, China planted (4 cultivars · 30 clones) in Sept. 2016. The plants were grown in arrays with Lin Cheng 30 cm between plants in the experimental College of Biology and Environment, Nanjing Forest University, Nanjing field; they were irrigated and fertilized simi- 210037, China larly to other perennial herbs. All plants were grown at a forest edge where they received half Shu-cheng Feng and Lei-lei Zhang full-sunlight. Morphological characteristics in- Research Center, Shanghai Botanical Garden, Shanghai, 200231, China; cluding plant height, leaf length and width, and Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Sustainable Plant Innovation, flower color, flower diameter, inner perianth length and width, outer perianth length and Shanghai 200231, China width, and the flowering period of the total Additional index words. cultivar, flower period, Iris japonica, ornamental, selection population. Single flowers were evaluated for a randomized sample of 15 plants per cultivar. Leaf length and width were measured on the Iris, with its showy and colorful flowers, is from late March to mid-April in Shanghai third leaf from the top of each plant. -

Pollen and Stamen Mimicry: the Alpine Flora As a Case Study

Arthropod-Plant Interactions DOI 10.1007/s11829-017-9525-5 ORIGINAL PAPER Pollen and stamen mimicry: the alpine flora as a case study 1 1 1 1 Klaus Lunau • Sabine Konzmann • Lena Winter • Vanessa Kamphausen • Zong-Xin Ren2 Received: 1 June 2016 / Accepted: 6 April 2017 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Many melittophilous flowers display yellow and Dichogamous and diclinous species display pollen- and UV-absorbing floral guides that resemble the most com- stamen-imitating structures more often than non-dichoga- mon colour of pollen and anthers. The yellow coloured mous and non-diclinous species, respectively. The visual anthers and pollen and the similarly coloured flower guides similarity between the androecium and other floral organs are described as key features of a pollen and stamen is attributed to mimicry, i.e. deception caused by the flower mimicry system. In this study, we investigated the entire visitor’s inability to discriminate between model and angiosperm flora of the Alps with regard to visually dis- mimic, sensory exploitation, and signal standardisation played pollen and floral guides. All species were checked among floral morphs, flowering phases, and co-flowering for the presence of pollen- and stamen-imitating structures species. We critically discuss deviant pollen and stamen using colour photographs. Most flowering plants of the mimicry concepts and evaluate the frequent evolution of Alps display yellow pollen and at least 28% of the species pollen-imitating structures in view of the conflicting use of display pollen- or stamen-imitating structures. The most pollen for pollination in flowering plants and provision of frequent types of pollen and stamen imitations were pollen for offspring in bees. -

Iridaceae – Iris Family

IRIDACEAE – IRIS FAMILY Plant: herbs, perennial; can be shrub-like elsewhere Stem: Root: growing from rhizomes, bulbs, or corms Leaves: simple, alternate or mostly basal (sheaths open or closed), most grass or sword-like with parallel veins Flowers: perfect, regular (actinomorphic) or irregular (zygomorphic); flowers showy, often solitary; flowers in 3’s (petals, sepals, and stamens), both sepals and petals often colored; regular as in Blue-Eyed grasses (looks like 6-plan), or irregular as in true Irises; flower subtended by 2 bracts; ovary mostly inferior, 3 carpels, 1 style Fruit: capsule with seed Other: Monocotyledons Group Genera: 65+ genera; locally Belamcanda (blackberry-lily), Iris (iris), Sisyrinchium (blue-eyed grass) WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive Flower Morphology in the Iridaceae (Iris Family) Examples of some common genera German Iris [Blue Flag] Iris germanica L. (Introduced Blackberry Lily Belamcanda chinensis (L.) DC. (Introduced) Dwarf Crested Iris Stout Blue-Eyed Grass Iris cristata Aiton Sisyrinchium angustifolium Mill. Copper [Red] Iris Iris fulva Ker Gawl. Prairie Blue-Eyed Grass Sisyrinchium campestre E.P. Bicknell IRIDACEAE – IRIS FAMILY Blackberry Lily; Belamcanda chinensis (L.) DC. (Introduced) Dwarf Crested Iris; Iris cristata Aiton Copper [Red] Iris; Iris fulva Ker Gawl. German Iris [Blue Flag]; Iris germanica L. (Introduced) Yellow Iris [Flag]; Iris pseudacorus L. (Introduced) Southern Blue Flag [Shreve's Iris]; Iris virginica L. var. shrevei (Small) E.S. Anderson Common Blue-Eyed Grass; Sisyrinchium albidum Raf. Stout Blue-Eyed Grass; Sisyrinchium angustifolium Mill. Eastern Blue-Eyed Grass; Sisyrinchium atlanticum E.P. Bicknell Prairie Blue-Eyed Grass; Sisyrinchium campestre E.P. -

Iris Sibirica and Others Iris Albicans Known As Cemetery

Iris Sibirica and others Iris Albicans Known as Cemetery Iris as is planted on Muslim cemeteries. Two different species use this name; the commoner is just a white form of Iris germanica, widespread in the Mediterranean. This is widely available in the horticultural trade under the name of albicans, but it is not true to name. True Iris albicans which we are offering here occurs only in Arabia and Yemen. It is some 60cm tall, with greyish leaves and one to three, strongly and sweetly scented, 9cm flowers. The petals are pure, bone- white. The bracts are pale green. (The commoner interloper is found across the Mediterranean basin and is not entitled to the name, which continues in use however. The wrongly named albicans, has brown, papery bracts, and off-white flowers). Our stock was first found near Sana’a, Yemen and is thriving here, outside, in a sunny, raised bed. Iris Sibirica and others Iris chrysographes Black Form Clumps of narrow, iris-like foliage. Tall sprays of darkest violet to almost black velvety flowers, Jun-Sept. Ht 40cm. Moist, well drained soil. Part shade. Deepest Purple which is virtually indistinguishable from black. Moist soil. Ht. 50cm Iris chrysographes Dykes (William Rickatson Dykes, 1911, China); Section Limniris, Series Sibericae; 14-18" (35-45 cm), B7D; Flowers dark reddish violet with gold streaks in the signal area giving it its name (golden writing); Collected by E. H. Wilson in 1908, in China; The Gardeners' Chronicle 49: 362. 1911. The Curtis's Botanical Magazine. tab. 8433 in 1912, gives the following information along with the color illustration. -

Entomologist Vot

l.!ay 1988 UARYLAND ENTOMOLoGIST Vot . 3 ( 2 ) Voh-rre 3 1988 [funber 2 CONTENTS Morgan, N. O. Tabanid (Diptera) survey at five horge farms in Maryland, 1984.. 25-29 Staines, C. L. The Dryopidae (Coleoptera) of Maryland .....30-32 Staines, C. L. & S. L. Staines. Observatlons on, new adult host plants for, CalllrhopaIus (Pseudoceorhlnus) blfasclatus (RoeIofs) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), with a revlew of host plants . .33-39 Stevenson, H. c. AII flve species of Metaxaglaea (Lepldoptera: Noctuidae, Cul I i inae ) at a single site in Tidelrater Maryland ...40-41 Staines, C. L. The Noteridae (Coleoptera) of Maryland EUPHYDRYAS " " '42-45 Stevenson, H. G. Dasychlra atrlvenosa (PaIm) (Lepldoptera: m Lynantriidae) in Tidewater Maryland..... ....46 Platt, A. P. Northern records of Papi.Ilo (HeracIldes) creEphontes (Cramer) (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) in the midwestern United states .....47-5I Book Review- Handbook of insect rearlng, E. J. cerberg......52 Stevenson, H. c. Xestla bolllt (Grote) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae, Noctuinae) in Tidewater Maryland..........53-54 iL Book Review- Insects, thelr blology and cultural hlstory, E. J- cerberg ....54 Editoral PoIicy of the Maryland Entomologist. , . .55-56 Editori.al .........29 Literature Notices . .29, 4L issued 20 May 1988 MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGIST MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGIST 3(2) t25-29 (1988) ICAL SOCIETY MARYLAID ENTOTOLG Iabanicl (Diptera) Survey at Five Horse Farms in Maryland, Executlve Conmlttee u 1 984 I Neal O. llorgan Austln P. Platt, Presldent Livestock Phll lp J. Kean, Vlce Presldent Insects Laboratory, USDA; ARS, Beltsvi11e, MD 20705 Robln G. Todd, Secretary-Treasurer Robert S. Bryant, Hlstorlan Abstract Thomas E. l{al lenmaler, Phaeton Edltor As parts of a potomac C. -

Ulster Group Newsletter 2013.Pdf

Newsletter No:12 Contents:- Editorial Obituaries Contributions:- Notes on Lilies Margaret and Henry Taylor Some Iris Species David Ledsham 2nd Czech International Rock Garden Conference Kay McDowell Homage to Catalonia Liam McCaughey Alpine Cuttings - or News Items Show News:- Information:- Web and 'Plant of the Month' Programme 2013 -2014 Editorial After a long cold spring I hope that all our members have been enjoying the beautiful summer, our hottest July for over 100 years. In the garden, flowers, butterflies and bees are revelling in the sunshine and the house martins, nesting in our eaves, are giving flying displays that surpass those of the Red Arrows. There is an emphasis ( almost a fashion) in horticultural circles at the moment on wild life gardening and wild flower meadows. I have always felt that alpines are the wild flowers of the mountains, whether growing in alpine meadows or nestling in among the rocks. Our Society aims to give an appreciation and thus the protection and conservation of wild flowers and plants all over the world. Perhaps you have just picked up this Newsletter and are new to the Society but whether you have a window pot or a few acres you would be very welcome to join the group and find out how much pleasure, in many different ways, these mountain wild flowers can bring. My thanks to our contributors this year who illustrate how varied our interest in plants can be. Not only did the Taylors give us a wonderful lecture and hands-on demonstration last November but kindly followed it up with an article for the Newsletter, and I hope that many of you, like me, have two healthy little pots of lily seedlings thanks to their generous gift of seeds. -

Society for Pacific Coast Native Irises ALMANAC

Society for Pacific Coast Native Irises ALMANAC www.pacificcoastiris.org Volume 40. No.1 Fall 2011 Brian Agron (bottom photo in a field of wild iris) has enjoyed the iris of Marin County, California ‐ complex hybrids derived from I. macrosiphon, I. fernaldii and I. douglasiana ‐ for more than thirty years. Read all about his love affair with Marin iris on page 18 of this issue. Cover photo: Iris tenax on Nicolai Mountain, OR. Photo: Kathleen Sayce Almanac of the Society for Pacific Coast Native Irises Volume XXXX, Number 1, Fall 2011 SPCNI MEMBERSHIP The Society for Pacific Coast Native Irises (SPCNI) is a section of the American Iris Society (AIS). Membership in AIS is recommended but not required for membership in SPCNI. US Overseas Annual, paper $15.00 $18.00 Triennial, paper $40.00 $48.00 Annual, digital $7.00 $7.00 Triennial, digital $19.00 $19.00 Lengthier memberships are no longer available. Please send membership fees to the SPCNI Treasurer. , Use Paypal to join SPCNI online at http://pacificcoastiris.org/JoinOnline.htm international currencies accepted IMPORTANT INFORMATION FROM THE SECRETARY/TREASURER ABOUT DUES NOTICES Members who get paper copies, please keep track of the expiration date of your membership, which is printed on your Almanac address label. We include a letter with your last issue, and may follow this with an email notice, if you have email. Members who get digital copies will get an email message after receiving the last issue. If you have a question about your membership expiration date, contact the Secretary. Also contact the Secretary if your contact information changes in any way, including phone, e‐mail and mailing addresses. -

SPRING WILDFLOWERS of OHIO Field Guide DIVISION of WILDLIFE 2 INTRODUCTION This Booklet Is Produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife As a Free Publication

SPRING WILDFLOWERS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE 2 INTRODUCTION This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any By Jim McCormac unauthorized reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wild- life and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) has a long history of promoting wildflower conservation and appreciation. ODNR’s landholdings include 21 state forests, 136 state nature preserves, 74 state parks, and 117 wildlife HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE areas. Collectively, these sites total nearly 600,000 acres Bloom Calendar Scientific Name (Scientific Name Pronunciation) Scientific Name and harbor some of the richest wildflower communities in MID MAR - MID APR Definition BLOOM: FEB MAR APR MAY JUN Ohio. In August of 1990, ODNR Division of Natural Areas and Sanguinaria canadensis (San-gwin-ar-ee-ah • can-ah-den-sis) Sanguinaria = blood, or bleeding • canadensis = of Canada Preserves (DNAP), published a wonderful publication entitled Common Name Bloodroot Ohio Wildflowers, with the tagline “Let Them Live in Your Eye Family Name POPPY FAMILY (Papaveraceae). 2 native Ohio species. DESCRIPTION: .CTIGUJQY[ƃQYGTYKVJPWOGTQWUYJKVGRGVCNU Not Die in Your Hand.” This booklet was authored by the GRJGOGTCNRGVCNUQHVGPHCNNKPIYKVJKPCFC[5KPINGNGCHGPYTCRU UVGOCVƃQYGTKPIVKOGGXGPVWCNN[GZRCPFUKPVQCNCTIGTQWPFGFNGCH YKVJNQDGFOCTIKPUCPFFGGRDCUCNUKPWU