De BELLANGE's HURDY-GURDY PLAYER: a CRITICAL DISCUSSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Press Release

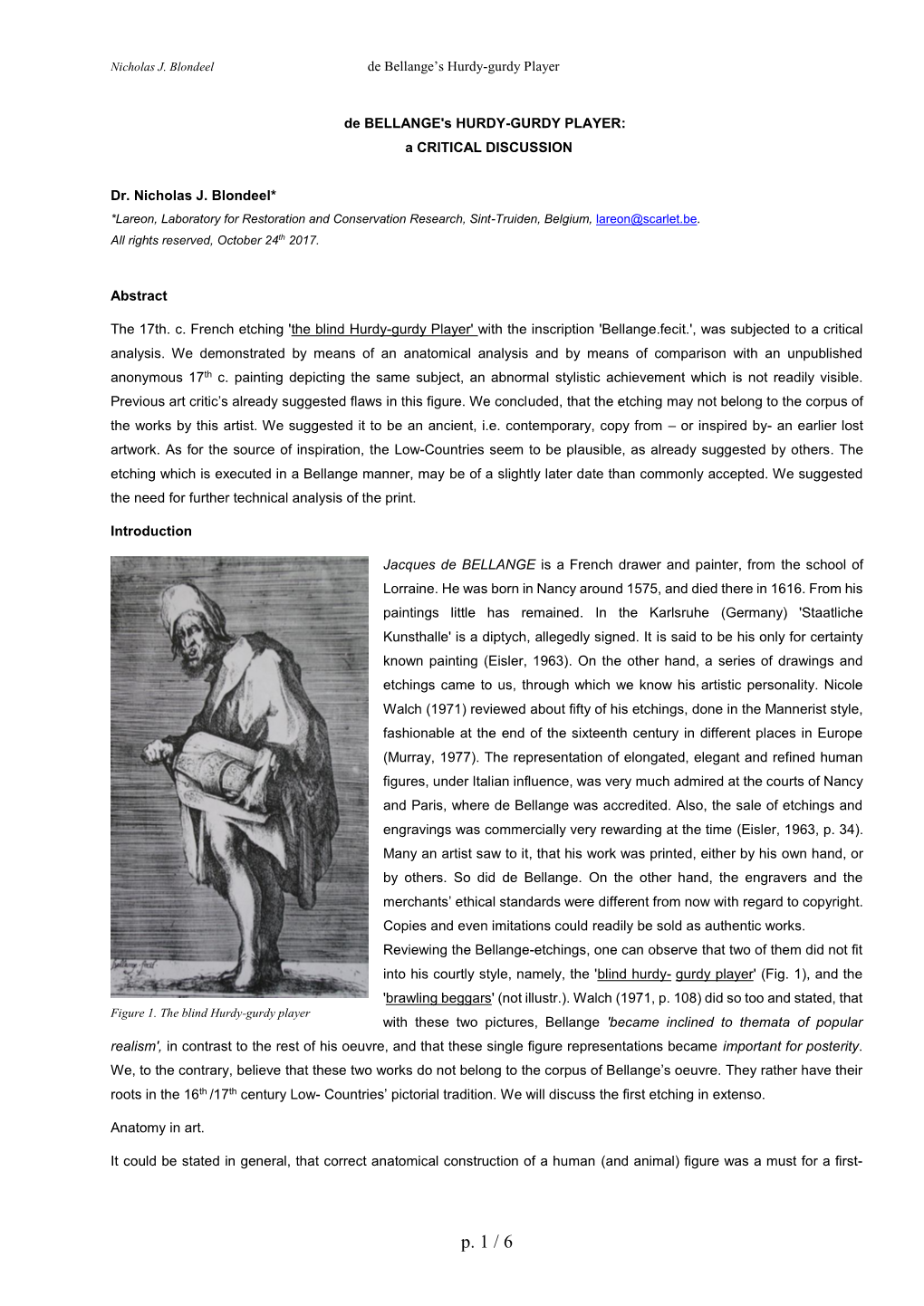

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] THE MORGAN HOSTS MAJOR EXHIBITION OF MASTER DRAWINGS FROM MUNICH’S FAMED STAATLICHE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG SHOW INCLUDES WORKS FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE MODERN PERIOD AND MARKS THE FIRST TIME THE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG HAS LENT SUCH AN IMPORTANT GROUP OF DRAWINGS TO AN AMERICAN MUSEUM Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich October 12, 2012–January 6, 2013 **Press Preview: Thursday, October 11, 10 a.m. until 11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, August 25, 2012—This fall, The Morgan Library & Museum will host an extraordinary exhibition of rarely- seen master drawings from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, one of Europe’s most distinguished drawings collections. On view October 12, 2012– January 6, 2013, Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich marks the first time such a comprehensive and prestigious selection of works has been lent to a single exhibition. Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) Italia and Germania, 1815–28 Dürer to de Kooning was conceived in Inv. 2001:12 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München exchange for a show of one hundred drawings that the Morgan sent to Munich in celebration of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung’s 250th anniversary in 2008. The Morgan’s organizing curators were granted unprecedented access to the Graphische Sammlung’s vast holdings, ultimately choosing one hundred masterworks that represent the breadth, depth, and vitality of the collection. The exhibition includes drawings by Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Flemish artists of the Renaissance and baroque periods; German draftsmen of the nineteenth century; and an international contingent of modern and contemporary draftsmen. -

Renaissance and Baroque Europe Author(S): Keith Christiansen, Nadine M

Renaissance and Baroque Europe Author(s): Keith Christiansen, Nadine M. Orenstein, William M. Griswold, Suzanne Boorsch, Clare Vincent, Donald J. LaRocca, Helen B. Mules, Walter Liedrke, Alice Zrebiec, Stuart W. Phyrr and Olga Raggio Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 52, No. 2, Recent Acquisitions: A Selection 1993-1994 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 20-35 Published by: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3258872 . Accessed: 02/06/2014 14:36 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.140.1.131 on Mon, 2 Jun 2014 14:36:29 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE Agostino Carracci Among the most innovativeworks of the late seem to support an attribution to his brother Italian (Bologna),1557-1602 sixteenth century are a small group of infor- Agostino, and, indeed, a composition of this or Annibale Carracci mal easel paintings treatingeveryday themes subject attributed to Agostino is listed in a Italian (Bologna),I560o-609 produced in the academy of the Carracci I680 inventory of the Farnesecollections in Two Children Teasinga Cat family in Bologna. -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

Prints, Drawings, and Photographs

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON Annual Report Acquisitions July 2014–June 2015: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs Albums Object No. Artist Title Culture/Date/Place Medium Credit Line 1. 2014.2255 Postcard album of stockyard and about 1910 Album with Gift of the Bressler family market scenes postcards 2. 2014.2256 Postcard album of Boston and about 1910 Album with Gift of the Bressler family New England scenes postcards Books and manuscripts Object No. Artist Title Culture/Date/Place Medium Credit Line 1. 2014.1156 Augustine Caldwell Old Ipswich in Verse Anonymous gift in honor of Bettina Arthur Wesley Dow (American, and Joe Gleason 1857–1922) 2. 2014.1157 China Painters' Blue Book Boston, Mass, 1897 Bound Book Anonymous gift in honor of Bettina and Joe Gleason 3. 2014.1169 Author: Hans Christian Andersen Favourite Fairy Tales about 1908 Illustrated book Gift of Meghan Melvin in honor of (Danish, 1805–1875) Maryon Wasilifsky Melvin Publisher: Blackie and Son, Ltd. Binding by: Talwin Morris (English, 1865–1911) Illustrated by: Helen Stratton (1867–1961) 4. 2014.1170 Author: Jonathan Swift (English, Gulliver's Travels Illustrated book Gift of Meghan Melvin in honor of 1667–1745) Maryon Wasilifsky Melvin Publisher: Blackie and Son, Ltd. Binding by: Talwin Morris (English, 1865–1911) Illustrated by: Gordon Browne (1858–1932) 5. 2014.1171 Author: Robert Michael Ballantyne Gascoyne The Sandal-Wood Illustrated book Gift of Meghan Melvin in honor of (Scottish, 1825 - 1894) Trader Maryon Wasilifsky Melvin Publisher: Blackie and Son, Ltd. Binding by: Talwin Morris (English, 1865–1911) Illustrated by: James F. Sloane Annual Report Acquisitions July 2014–June 2015: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs Page 2 of 303 Books and manuscripts Object No. -

Annual Report 1976

1976 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-173826 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1977, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art Photograph on page 82 by Stewart Brothers; all other photographs by the photographic staff of the National Gallery of Art. This publication was produced by the Editor's Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Baltimore, Maryland. The type is Bodoni Book, set by Monotype Composition Company, Baltimore, Maryland Designed by Susan Lehmann, Washington Frontispiece: The Triumph of Reason and Order over Chaos and War, the fireworks display that opened the Bicentennial exhibition, The Eye of Thomas Jefferson CONTENTS 6 ORGANIZATION 9 DIRECTOR'S REVIEW OF THE YEAR 25 DONORS AND ACQUISITIONS 41 LENDERS 45 NATIONAL PROGRAMS 45 Department of Extension Programs 46 Loans to Temporary Exhibitions 49 Loans from the Gallery's Collections 52 EDUCATIONAL SERVICES 57 DEPARTMENTAL REPORTS 57 Curatorial Departments 59 Library 60 Photographic Archives 60 Conservation Department 62 Editor's Office 63 Exhibitions and Loans 63 Registrar's Office 63 Installation and Design 65 Photographic Laboratory Services 67 STAFF ACTIVITIES 73 ADVANCED STUDY AND RESEARCH, AND SCHOLARLY PUBLICATIONS 75 MUSIC AT THE GALLERY 78 PUBLICATIONS SERVICE 79 BUILDING MAINTENANCE, SECURITY AND ATTENDANCE 80 APPROPRIATIONS 81 OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY AND GENERAL COUNSEL 83 EAST BUILDING 85 ROSTER OF EMPLOYEES ORGANIZATION The 39th annual report of the National Gallery of Art reflects an- other year of continuing growth and change. -

Annual Report 1964

REPORT ON THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART 1964 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON D.C. REPORT ON THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 1964 From the Smithsonian Report for 1964 Pages 217-230 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1965 • Report on the National Gallery of Art SIR : I have the honor to submit, on behalf of the Board of Trustees, the 27th annual report of the National Gallery of Art, for the fiscal year ended June 30,1964. This report is made pursuant to the provi- sions of section 5(d) of Public Resolution No. 14, 75th Congress, 1st session, approved March 24,1937 (50 Stat. 51). ORGANIZATION The statutory members of the Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art are the Chief Justice of the United States, the Secre- tary of State, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, ex officio. On January 9, 1964, Lessing J. Rosenwald and Dr. Franklin D. Murphy were elected general trustees of the National Gallery of Art. The three other general trustees con- tinuing in office during the fiscal year ended June 30, 1964, were Paul Mellon, John Hay Whitney, and John N. Irwin II. On May 7,1964, Paul Mellon was reelected by the Board of Trustees to serve as presi- dent of the Gallery, and John Hay Whitney was reelected vice presi- dent. On January 9, 1964, J. Carter Brown was elected assistant director. The executive officers of the Gallery as of June 30, 1964, were as follows: Chief Justice of the United States, John Walker, Director. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 ADVANCE SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS SPRING 2005 THROUGH FALL 2006 PLEASE NOTE: The information provided below is a partial listing and is subject to change. Before publication, please confirm scheduling by calling the Media Relations & Marketing Department at (212) 547-6844 or by emailing [email protected]. CURRENT AND UPCOMING PRESENTATIONS GARDENS OF ETERNAL SPRING: TWO NEWLY CONSERVED MUGHAL CARPETS May 10 through August 14, 2005 This spring and summer, visitors to The Frick Collection have an opportunity to see two of the finest surviving examples of the carpet weaver’s art. These recently conserved Mughal carpets, one of which has never before been shown by the museum, are extremely rare and important fragments of larger works, and their exhibition has been keenly anticipated by enthusiasts and scholars in the field. Their treatment was undertaken by pre-eminent textile conservator Nobuko Kajitani, who has painstakingly returned the rugs to their original splendor over a period of four years. She first removed later embroidery and fringe; then—bearing in mind the appearance of the original larger carpets from which they derive as well as their present state—she correctly rearranged the fragments in keeping with the original mid-seventeenth-century compositions. Thanks to this successful conservation project, it is now possible to admire the dazzling array of trees and flowers portrayed on the carpets’ surface. Presented as works of art in their own right, the carpets are installed in the Frick’s Oval Room through August 14, 2005. -

Jacques Callot and the Baroque Print, June 17, 2011-November 6, 2011

Jacques Callot and the Baroque Print, June 17, 2011-November 6, 2011 One of the most prolific and versatile graphic artists in Western art history, the French printmaker Jacques Callot created over 1,400 prints by the time he died in 1635 at the age of forty-three. With subjects ranging from the frivolous festivals of princes to the grim consequences of war, Callot’s mixture of reality and fanciful imagination inspired artists from Rembrandt van Rijn in his own era to Francisco de Goya two hundred years later. In these galleries, Callot’s works are shown next to those of his contemporaries to gain a deeper understanding of his influence. Born into a noble family in 1592 in Nancy in the Duchy of Lorraine (now France), Callot traveled to Rome at the age of sixteen to learn printmaking. By 1614, he was in Florence working for Cosimo II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. After the death of the Grand Duke in 1621, Callot returned to Nancy, where he entered the service of the dukes of Lorraine and made prints for other European monarchs and the Parisian publisher Israël Henriet. Callot perfected the stepped etching technique, which consisted of exposing copperplates to multiple acid baths while shielding certain areas from the chemical with a hard, waxy ground (see the book illustration in the adjoining gallery). This process contributed to different depths of etched lines and thus striking light and spatial qualities when the plate was inked and printed. Callot may have invented the échoppe, a tool with a curved tip that he used to sweep through the hard ground to create curved and swelled lines in imitation of engraving. -

Contact Jonathan Gaugler [email protected] 412.688.8690 412.216.7909

Contact Jonathan Gaugler [email protected] 412.688.8690 412.216.7909 Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces, on the walls and under the microscope Summer exhibitions at CMOA present Old Master prints, and forensic investigations of paintings Small Prints, Big Artists: Masterpieces from the Renaissance to Baroque May 31–September 15, 2014 Heinz Galleries A & B Faked, Forgotten, Found: Five Renaissance Paintings Investigated June 28–September 15, 2014 Heinz Gallery C Around the middle of the 15th century, as the development of the printing press in the West led to an unprecedented exchange of ideas, artists began to make prints. By the year 1500, a new art form and a new means of communicating ideas was widespread—one that had as great an impact in its time as the Internet has had in our own. Carnegie Museum of Art holds an exceptional collection of prints from this period, from the masterful innovations of Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt in 15th- and 16th-century Northern Europe to the fantastical prints of Canaletto, Tiepolo, and Piranesi in 18th-century Italy. Small Prints, Big Artists, opening this summer, presents more than 200 masterworks from the museum’s exceptional collection of nearly 9,000 prints. The intimately scaled woodcuts, engravings, and etchings reveal the development of printmaking as a true art form. Due to their fragility, many of these prints have not been on view in decades. Small Prints, Big Artists traces the development of prints over the centuries, exploring the evolution of printmaking techniques and unlocking the images’ hidden meanings. It offers a unique opportunity to discover works by some of the best-known artists of the Renaissance and beyond. -

Old Master Prints

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6n39n8g8 Online items available Old Master Prints Processed by Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Layna White Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles 10899 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, California 90024-4201 Phone: (310) 443-7078 Fax: (310) 443-7099 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.hammer.ucla.edu © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Old Master Prints 1 Old Master Prints Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, California Contact Information Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles 10899 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, California 90024-4201 Phone: (310) 443-7078 Fax: (310) 443-7099 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.hammer.ucla.edu Processed by: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum staff Date Completed: 2/21/2003 Encoded by: Layna White © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Old Master Prints Repository: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum Los Angeles, CA 90024 Language: English. Publication Rights For publication information, please contact Susan Shin, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, [email protected] Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Collection of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA. [Item credit line, if given] Notes In 15th-century Europe, the invention of the printed image coincided with both the wide availability of paper and the invention of moveable type in the West. -

Georges De La Tour's Flea-Catcher and the Iconography of the Flea-Hunt in Seventeenth-Century Baroque Art" (2007)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Georges de La Tour's Flea-Catcher and the iconography of the flea-hunt in seventeenth- century Baroque art Crissy Bergeron Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Bergeron, Crissy, "Georges de La Tour's Flea-Catcher and the iconography of the flea-hunt in seventeenth-century Baroque art" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 462. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/462 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGES DE LA TOUR’S FLEA-CATCHER AND THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE FLEA-HUNT IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY BAROQUE ART A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Crissy Bergeron B.A., Northwestern State University, 2001 May 2007 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………...……………………iii Chapter 1 Introduction…………………….…………………………..……………………….1 2 The Flea-Catcher and Catholic Iconography……………..………………………18 3 Sexual Connotations of the Flea in Word and Image……………………….…….32 4 Conclusion……………………………………………………...…………………44 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..………………47 Vita……………………………………………………………………………………….51 ii Abstract This essay performs a comprehensive investigation of the thematic possibilities for Georges de La Tour’s Flea-Catcher (1630s-1640s) based on related artworks, religion, and emblematic, literary, and pseudo-scientific texts that may have had a bearing on it. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 STUNNING DRAWINGS FROM WEIMAR MUSEUMS TO BE PRESENTED IN THE UNITED STATES FOR THE FIRST TIME Core of these Little-Known Collections Connected to Goethe June 1 through August 7, 2005 From Callot to Greuze: French Drawings from Weimar, an exhibition opening on June 1, 2005, at The Frick Collection presents to American audiences a selection of approximately seventy drawings from the Schlossmuseum and the Goethe-Nationalmuseum in Weimar, Germany, and offers a unique viewing opportunity as many of these works have never before been seen outside of the former Eastern bloc countries. (The two institutions—with their collections, gardens, and buildings— united in 2003 and are now known as Stiftung Weimarer Klassik und Kunstsammlungen.) The accompanying catalogue also marks the first François Boucher (1703–1770) time that many of these masterworks have been published. Sheets by A Triton Holding a Stoup in His Hands, date unknown Stumped black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on cream paper, 328 x 297 mm Jacques Callot, Charles Lebrun, Claude Lorrain, Jacques Bellange, Schlossmuseum–KK 9000 Simon Vouet, Jean-Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, Charles-Joseph Natoire, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Charles-Louis Clérisseau, among others, are included, promising to shed new light on the individual oeuvres of these artists as well as deepen our understanding of their practice as draftsmen within the context of other French masters. Comments Anne L. Poulet, Director of The Frick Collection, “this project presents the most complete assessment to date of Weimar’s French seventeenth- and eighteenth-century drawings, and we are pleased to offer most of our visitors—with both the exhibition and publication—their first viewing of this incredible collection.