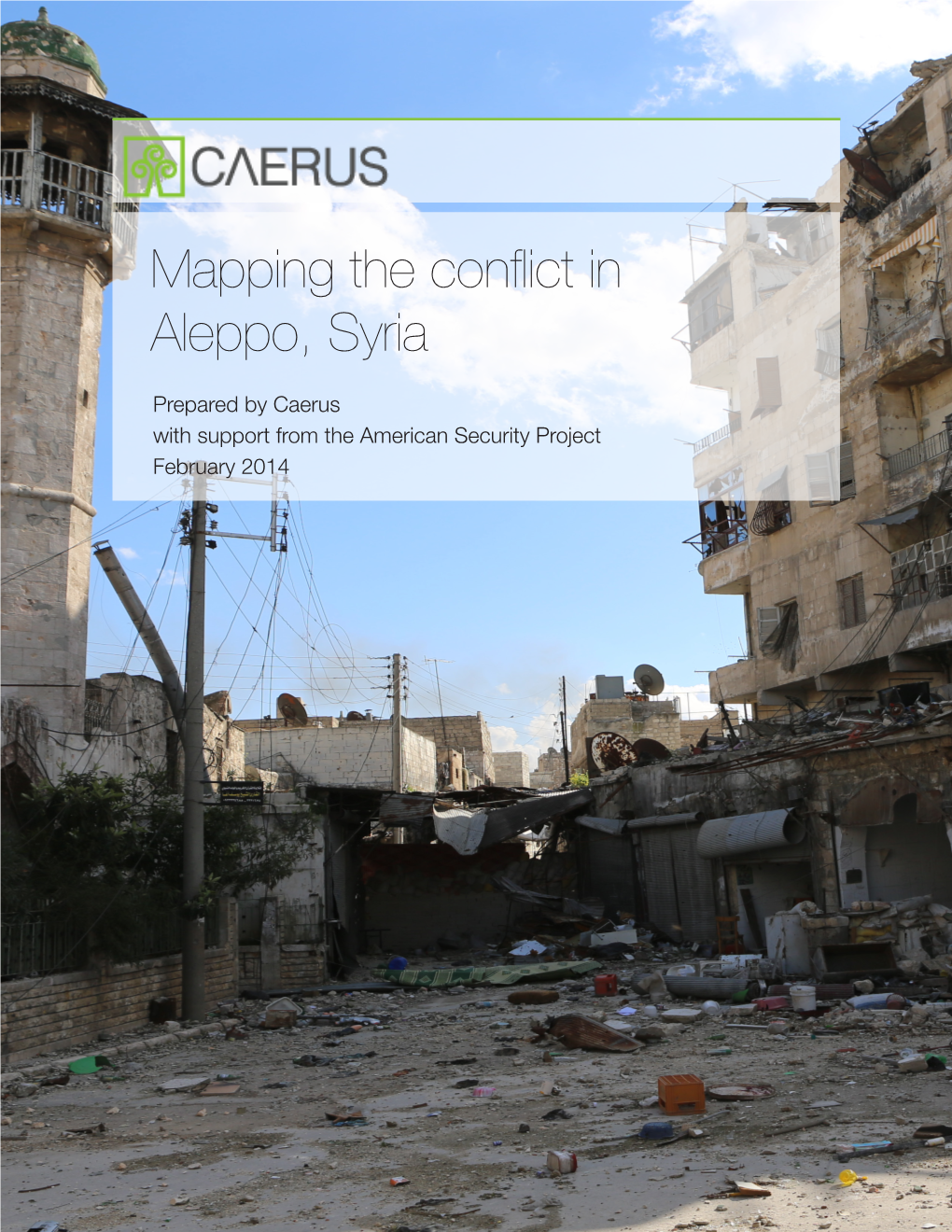

Mapping the Con Ict in Aleppo, Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Hezbollah's Syrian Quagmire

Hezbollah’s Syrian Quagmire BY MATTHEW LEVITT ezbollah – Lebanon’s Party of God – is many things. It is one of the dominant political parties in Lebanon, as well as a social and religious movement catering first and fore- Hmost (though not exclusively) to Lebanon’s Shi’a community. Hezbollah is also Lebanon’s largest militia, the only one to maintain its weapons and rebrand its armed elements as an “Islamic resistance” in response to the terms of the Taif Accord, which ended Lebanon’s civil war and called for all militias to disarm.1 While the various wings of the group are intended to complement one another, the reality is often messier. In part, that has to do with compartmen- talization of the group’s covert activities. But it is also a factor of the group’s multiple identities – Lebanese, pan-Shi’a, pro-Iranian – and the group’s multiple and sometimes competing goals tied to these different identities. Hezbollah insists that it is Lebanese first, but in fact, it is an organization that always acts out of its self-interests above its purported Lebanese interests. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, Hezbollah also has an “expansive global network” that “is sending money and operatives to carry out terrorist attacks around the world.”2 Over the past few years, a series of events has exposed some of Hezbollah’s covert and militant enterprises in the region and around the world, challenging the group’s standing at home and abroad. Hezbollah operatives have been indicted for the murder of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri by the UN Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) in The Hague,3 arrested on charges of plotting attacks in Nigeria,4 and convicted on similar charges in Thailand and Cyprus.5 Hezbollah’s criminal enterprises, including drug running and money laundering from South America to Africa to the Middle East, have been targeted by law enforcement and regulatory agen- cies. -

In the Name of the Displaced Afrin People in Shehba to the World Health Organization

الهﻻل اﻷحمر الكردي HEYVA SOR A KURD فرع عفرين ŞAXÊ EFRÎNÊ In the name of the displaced Afrin people in Shehba To the World Health Organization The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), issued a report regarding the emergence of corona virus (COVID-19) in the Syrian Republic on / 11th of March 2020 /, the report stated that the Syrian Ministry of Health confirmed the negative of all cases that were suspected and no one was infected. To counter the threat of the virus, the World Health Organization provides all means of support and assistance to the Syrian Ministry of Health to supplement its ability and preparedness to address this epidemic by providing detection and monitoring equipment, training health personnel in several governorates, and providing quarantine centers in addition to holding workshops aimed at enhancing awareness and understanding the risks of the epidemic. The report stated that the readiness of isolation centers was confirmed in / 6 / areas, namely (Damascus, Aleppo, Deir Al-Zour, Homs, Lattakia and Qamishli) and a health center is currently being established that deals with corona cases in Dwer region in the Damascus countryside. What about more than two hundred thousand displaced people in the northern countryside of Aleppo (Al-Shahba)? Through the report, we see great efforts to help the Syrians ward off the threat of this epidemic, but it is very clear that they forgot a very large geographical spot in which thousands of displaced people are present, and whose presence has reached two years, amid great disregard from the World Health Organization and the Syrian government as well. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

When Maqam Is Reduced to a Place Eyal Sagui Bizawe

When Maqam is Reduced to a Place Eyal Sagui Bizawe In March 1932, a large-scale impressive festival took place at the National Academy of Music in Cairo: the first international Congress of Arab Music, convened by King Fuad I. The reason for holding it was the King’s love of music, and its aim was to present and record various musical traditions from North Africa and the Middle East, to study and research them. Musical delegations from Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Morocco, Algiers, Tunisia and Turkey entered the splendid building on Malika Nazli Street (today Ramses Street) in central Cairo and in between the many performances experts discussed various subjects, such as musical scales, the history of Arab music and its position in relation to Western music and, of course: the maqam (pl. maqamat), the Arab melodic mode. The congress would eventually be remembered, for good reason, as one of the constitutive events in the history of modern Arab music. The Arab world had been experiencing a cultural revival since the 19th century, brought about by reforms introduced under the Ottoman rule and through encounters with Western ideas and technologies. This renaissance, termed Al-Nahda or awakening, was expressed primarily in the renewal of the Arabic language and the incorporation of modern terminology. Newspapers were established—Al-Waq’i’a al-Masriya (Egyptian Affairs), founded under orders of Viceroy and Pasha Mohammad Ali in 1828, followed by Al-Ahram (The Pyramids), first published in 1875 and still in circulation today; theaters were founded and plays written in Arabic; neo-classical and new Arab poetry was written, which deviated from the strict rules of classical poetry; and new literary genres emerged, such as novels and short stories, uncommon in Arab literature until that time. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

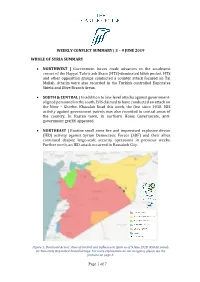

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

Download the Publication

Viewpoints No. 99 Mission Impossible? Triangulating U.S.- Turkish Relations with Syria’s Kurds Amberin Zaman Public Policy Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center; Columnist, Diken.com.tr and Al-Monitor Pulse of the Middle East April 2016 The United States is trying to address Turkish concerns over its alliance with a Syrian Kurdish militia against the Islamic State. Striking a balance between a key NATO ally and a non-state actor is growing more and more difficult. Middle East Program ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ On April 7 Syrian opposition rebels backed by airpower from the U.S.-led Coalition against the Islamic State (ISIS) declared that they had wrested Al Rai, a strategic hub on the Turkish border from the jihadists. They hailed their victory as the harbinger of a new era of rebel cooperation with the United States against ISIS in the 98-kilometer strip of territory bordering Turkey that remains under the jihadists’ control. Their euphoria proved short-lived: On April 11 it emerged that ISIS had regained control of Al Rai and the rest of the areas the rebels had conquered in the past week. Details of what happened remain sketchy because poor weather conditions marred visibility. But it was still enough for Coalition officials to describe the reversal as a “total collapse.” The Al Rai fiasco is more than just a battleground defeat against the jihadists. It’s a further example of how Turkey’s conflicting goals with Washington are hampering the campaign against ISIS. For more than 18 months the Coalition has been striving to uproot ISIS from the 98- kilometer chunk of the Syrian-Turkish border that is generically referred to the “Manbij Pocket” or the Marea-Jarabulus line. -

00. the Realization of Negation in the Syrian Arabic Clause, Phrase, And

The realization of negation in the Syrian Arabic clause, phrase, and word Isa Wayne Murphy M.Phil in Applied Linguistics Trinity College Dublin 2014 Supervisor: Dr. Brian Nolan Declaration I declare that this dissertation has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and that it is entirely my own work. I agree that the Library may lend or copy this dissertation on request. Signed: Date: 2 Abstract The realization of negation in the Syrian Arabic clause, phrase, and word Isa Wayne Murphy Syrian Arabic realizes negation in broadly the same way as other dialects of Arabic, but it does so utilizing varied and at times unique means. This dissertation provides a Role and Reference Grammar account of the full spectrum of lexical, morphological, and analytical means employed by Syrian Arabic to encode negation on the layered structures of the verb, the clause, the noun, and the noun phrase. The scope negation takes within the LSC and the LSNP is identified and illustrated. The study found that Syrian Arabic employs separate negative particles to encode wide-scope negation on clauses and narrow-scope negation on constituents, and utilizes varied and interesting means to express emphatic negation. It also found that while Syrian Arabic belongs in most respects to the broader Levantine family of Arabic dialects, its negation strategy is more closely aligned with the Arabic dialects of Iraq and the Arab Gulf states. 3 Table of Contents DECLARATION......................................................................................................................... -

Download S/2013/735

United Nations A/68/663–S/2013/735 General Assembly Distr.: General 13 December 2013 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-eighth session Sixty-eighth year Agenda item 33 Prevention of armed conflict Identical letters dated 13 December 2013 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the General Assembly and the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the final report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (see annex). I would be grateful if the present final report, the letter of transmittal and its appendices could be brought to the attention of the Members of the General Assembly and of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 13-61784 (E) 131213 *1361784* A/68/663 S/2013/735 Annex Letter of transmittal Having completed our investigation into the allegations of the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic reported to you by Member States, and further to the report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (hereinafter, the “United Nations Mission”) on allegations of the use of the chemical weapons in the Ghouta area of Damascus on 21 August 2013 (A/67/997-S/2013/553), we have the honour to submit the final report of the United Nations Mission. To date, 16 allegations of separate incidents involving the use of chemical weapons have been reported to the Secretary-General by Member States, including, primarily, the Governments of France, Qatar, the Syrian Arab Republic, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America. -

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001 Weekly Report 2 — August 18, 2014 Michael D. Danti Heritage Timeline August 16 APSA website released a video and a short report on alleged looting at Deir Turmanin (5th Century AD) in Idlib Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-018. • DGAM posted a report on alleged vandalism/looting and combat damage sustained to the Roman/Byzantine Beit Hariri (var. Zain al-Abdeen Palace) of the 2nd Century AD in Inkhil, Daraa Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-017. • Heritage for Peace released its weekly report Damage to Syria’s Heritage 17 August 2014. August 15 DGAM posts short report Burning of the Historic Noria Gaabariyya in Hama. Cf. SHI Incident Report SHI14-006 dated Aug. 9. DGAM report provides new photos of the fire damage. SHI Report Update SHI14-006. August 14 Chasing Aphrodite website posted an article entitled Twenty Percent: ISIS “Khums” Tax on Archaeological Loot Fuels the Conflicts in Syria and Iraq featuring an interview between CA’s Jason Felch and Dr. Amr al-Azm of Shawnee State University. • Damage to a 6th century mosaic from al-Firkiya in the Maarat al-Numaan Museum. Source: Smithsonian Newsdesk report. SHI Incident Report SHI14-016. • Aleppo Archaeology website posted a video showing damage in the area south of the Aleppo Citadel — much of the damage was caused by the July 29 tunnel bombing of the Serail by the Islamic Front. https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=739634902761700&set=vb.4596681774 25042&type=2&theater SHI Incident Report Update SHI14-004. -

Consumed by War the End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’S Political Order

STUDY Consumed by War The End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’s Political Order KHEDER KHADDOUR October 2017 n The fall of Eastern Aleppo into rebel hands left the western part of the city as the re- gime’s stronghold. A front line divided the city into two parts, deepening its pre-ex- isting socio-economic divide: the west, dominated by a class of businessmen; and the east, largely populated by unskilled workers from the countryside. The mutual mistrust between the city’s demographic components increased. The conflict be- tween the regime and the opposition intensified and reinforced the socio-economic gap, manifesting it geographically. n The destruction of Aleppo represents not only the destruction of a city, but also marks an end to the set of relations that had sustained and structured the city. The conflict has been reshaping the domestic power structures, dissolving the ties be- tween the regime in Damascus and the traditional class of Aleppine businessmen. These businessmen, who were the regime’s main partners, have left the city due to the unfolding war, and a new class of business figures with individual ties to regime security and business figures has emerged. n The conflict has reshaped the structure of northern Syria – of which Aleppo was the main economic, political, and administrative hub – and forged a new balance of power between Aleppo and the north, more generally, and the capital of Damascus. The new class of businessmen does not enjoy the autonomy and political weight in Damascus of the traditional business class; instead they are singular figures within the regime’s new power networks and, at present, the only actors through which to channel reconstruction efforts.