Aleppo of Aleppo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

16 Phase 4D Late Medieval and Renaissance Fortification 1350–1600 AD

Metro Cityring – Kongens Nytorv KBM 3829, Excavation Report 16 Phase 4d Late medieval and Renaissance fortification 1350–1600 AD 16.1 Results The presentation of the remains from Phase 4d will be given from two perspectives. Firstly there will be an account of the different feature types – part of a bulwark and the Late medieval moat (Fig. 140 and Tab. 37). After the overall description the features are placed in a structural and historical context. This time phase could have been presented together with either the eastern gate building and/or the Late medieval city wall, but is separated in the report due to the results and dates, interpretations and the general discussion on the changes that have been made on the overall fortification over time. This also goes for the backfilling and levelling of the Late medieval moat which actually should be placed under time Phase 6 (Post medieval fortification and other early 17th century activities), but are presented here due to the difficulties in distinguishing some of these deposits from the usage layers and the fact that these layers are necessary for the discussion about the moat’s final destruction, etc. Museum of Copenhagen 2017 248 Metro Cityring – Kongens Nytorv KBM 3829, Excavation Report Fig. 140. Overview of Late medieval features at Kongens Nytorv. Group Type of feature Subarea Basic interpretation 502976 Timber/planks Trench ZT162033 Bulwark 503806 Cut and fills Station Box Ditch? 450 Construction cut, sedimentation and Several phases Moat, 16th century backfills 560 Dump and levelling layers Phase 5B-2 Moat, 16th century 500913 Timber Phase 5A-1 Wooden plank Tab. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

“Moat” Strategy in Real Estate Warren Buffett Buys Investments with “Economic Moats” in Order to Earn Safer, Higher Returns

HOW TO INVEST IN REAL HOW I LEARNED TO STOP I HAVE EVERY DOLLAR I’VE WHY COMPOUND ARE YOU MISSING ESTATE WITHOUT OWNING STOCK PICKING AND LOVE EARNED IN MY 10 YEAR INTEREST ISN’T AS OPPORTUNITIES TO SAVE REAL ESTATE INDEX FUNDS CAREER POWERFUL AS YOU THINK $100,000+ IN ORDER TO (http://www.investmentzen(h.ctotpm://bwlwogw/.hinovwe-stmentzen(h.ctotpm://bwlwogw/.hinovwe-stmentzen(h.ctotpm://bwlwogw/.ii-nvestmentzenS.cAoVmE P/bENloNgIE/wS?hy- HOME (HTTP://WWW.INVESTMENTZEN.COM/BLOG/) » REAL ESTATE INVESTING (HTTP://WWW.INVESTMENTZEN.COM/BLOG/TOPICS/REAL-ESTATE/) JUNE 26, 2017 How To Use Warren Buffett’s “Moat” Strategy In Real Estate Warren Buffett buys investments with “economic moats” in order to earn safer, higher returns. You can use the same concept to buy protable real estate investments. Here’s how. j Sh3a1re s Tw3e2et b Pin1 a Reddit q Stumble B Pocketz Bu2ff2er h +1 2 k Email o 88 SHARES (https://www.(rhetdtpd:it//.wcowmw/.ssutubmbitl?euurpl=ohnt.tcpo:m//w/swuwb.minivt?eusrtml=hentttpz:e//nw.cwowm.i/nbvloegs/thmoewn-ttzoe-nu.sceo-mwa/brlroegn/-hbouwff-ettots-u-mseo-awta-srrtreant-ebguyf-fetts-moat- RELATED POSTS HOW TO INVEST IN REAL ESTATE WITHOUT OWNING REAL ESTATE (tiewornhoeswi-ta-tritnahlnep-tioavn:e/uelg-/-st)w--t-ww.(ihntvteps:/t/mwewnwtz.einnv.ceostmm/benlotgz/ehno.cwo-m/blog/how- to-invest-in-real-estate- CHAD CARSON without-owning-real- (HTTP://WWW.INVESTMENTZEN.COM/BLOG/AUTHOR/COACHCARSON/) estate/) Real estate investor, world traveler, husband & INVESTING IN REAL ESTATE VS STOCKS: PICKING A SIDE father of 2 (http://www.investmentzen.com/blog/real- (esminhtsovatttaecrpkst:et-/i-/tnvw-gsw-/)w.einstvaetset-mvse-nsttozcekn-.mcoamrk/belto- g/real- investing/) I’m a Warren Buffett nerd. -

(CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA021 May 2018 Monthly Report — May 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, William Raynolds, Darren Ashby, Gwendolyn Kristy, Nour Halabi, Kyra Kaercher, Jamie O’Connell Report coordinated by: Marina Gabriel Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 13 Incident Reports: Iraq 99 Incident Reports: Libya 111 Satellite Imagery and Geospatial Analysis 114 SNHR Vital Facilities Report 122 SNHR Videos 122 Heritage Timeline 123 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points Syria ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Alleged Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters vandalized the Shrine of Sheikh Zaid located in the Zaidiya Cemetery in Afrin, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0105. ○ Alleged Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters looted the Shrine of Sheikh Junayd in Qarabash, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0108 ○ Alleged Turkish army forces destroyed the grave of the Kurdish writer Nuri Dersimi and damaged Henan Mosque in Mesh’ale, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0116 ● Damascus Governorate ○ New photographs show damage to al-Habib al-Mustafa Mosque in Yarmouk neighborhood, Damascus, Damascus Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0099 ○ Reported SARG forces recaptured the Jerusalem Mosque in Yarmouk neighborhood, Damascus, Damascus Governorate. -

Searching for Viking Age Fortresses with Automatic Landscape Classification and Feature Detection

remote sensing Article Searching for Viking Age Fortresses with Automatic Landscape Classification and Feature Detection David Stott 1,2, Søren Munch Kristiansen 2,3,* and Søren Michael Sindbæk 3 1 Department of Archaeological Science and Conservation, Moesgaard Museum, Moesgård Allé 20, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark 2 Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Høegh-Guldbergs Gade 2, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 3 Center for Urban Network Evolutions (UrbNet), Aarhus University, Moesgård Allé 20, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-2338-2424 Received: 19 June 2019; Accepted: 25 July 2019; Published: 12 August 2019 Abstract: Across the world, cultural heritage is eradicated at an unprecedented rate by development, agriculture, and natural erosion. Remote sensing using airborne and satellite sensors is an essential tool for rapidly investigating human traces over large surfaces of our planet, but even large monumental structures may be visible as only faint indications on the surface. In this paper, we demonstrate the utility of a machine learning approach using airborne laser scanning data to address a “needle-in-a-haystack” problem, which involves the search for remnants of Viking ring fortresses throughout Denmark. First ring detection was applied using the Hough circle transformations and template matching, which detected 202,048 circular features in Denmark. This was reduced to 199 candidate sites by using their geometric properties and the application of machine learning techniques to classify the cultural and topographic context of the features. Two of these near perfectly circular features are convincing candidates for Viking Age fortresses, and two are candidates for either glacial landscape features or simple meteor craters. -

Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2016 English Original: Arabic

United Nations S/2016/534 Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2016 English Original: Arabic Identical letters dated 13 June 2016 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council On instructions from my Government, I should like to draw your attention to the following information regarding terrorist acts committed by armed terrorist groups active in Syrian territory during the month of May 2016: 3 May • Some 19 people were killed and more than 65 others were injured, including women and children, when armed terrorist groups fired dozens of shells at Dubayt Hospital and other neighbourhoods in the city of Aleppo and its countryside. • A civilian was killed when a mortar shell landed in Khan al-Shaykh in Rif Dimashq. • A mortar shell landed in Dar‘a, injuring a civilian. • A mortar shell landed in the Tahtuh neighbourhood in Dayr al-Zawr, injuring a civilian. 4 May • Four civilians were killed and more than 15 others were injured, including women and children, when dozens of shells fell in several neighbourhoods of the city of Aleppo and its countryside. • The terrorist Nusrah Front organization perpetrated a massacre in the village of Khuwayn in Idlib, killing 15 civilians, including four children. 5 and 6 May • On Thursday, 12 civilians were killed and 40 injured when terrorist explosions occurred in the city of Upper Mukharram in the Homs countryside. • Terrorist groups fired several shells at the Maydan neighbourhood in Aleppo, killing one civilian and injuring another. Material damage was caused. -

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

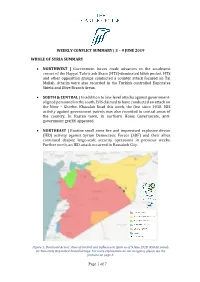

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

State Party Report

Ministry of Culture Directorate General of Antiquities & Museums STATE PARTY REPORT On The State of Conservation of The Syrian Cultural Heritage Sites (Syrian Arab Republic) For Submission By 1 February 2018 1 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. Damascus old city 5 Statement of Significant 5 Threats 6 Measures Taken 8 2. Bosra old city 12 Statement of Significant 12 Threats 12 3. Palmyra 13 Statement of Significant 13 Threats 13 Measures Taken 13 4. Aleppo old city 15 Statement of Significant 15 Threats 15 Measures Taken 15 5. Crac des Cchevaliers & Qal’at Salah 19 el-din Statement of Significant 19 Measure Taken 19 6. Ancient Villages in North of Syria 22 Statement of Significant 22 Threats 22 Measure Taken 22 4 INTRODUCTION This Progress Report on the State of Conservation of the Syrian World Heritage properties is: Responds to the World Heritage on the 41 Session of the UNESCO Committee organized in Krakow, Poland from 2 to 12 July 2017. Provides update to the December 2017 State of Conservation report. Prepared in to be present on the previous World Heritage Committee meeting 42e session 2018. Information Sources This report represents a collation of available information as of 31 December 2017, and is based on available information from the DGAM braches around Syria, taking inconsideration that with ground access in some cities in Syria extremely limited for antiquities experts, extent of the damage cannot be assessment right now such as (Ancient Villages in North of Syria and Bosra). 5 Name of World Heritage property: ANCIENT CITY OF DAMASCUS Date of inscription on World Heritage List: 26/10/1979 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANTS Founded in the 3rd millennium B.C., Damascus was an important cultural and commercial center, by virtue of its geographical position at the crossroads of the orient and the occident, between Africa and Asia. -

Fortification Renaissance: the Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne

FORTIFICATION RENAISSANCE: THE ROMAN ORIGINS OF THE TRACE ITALIENNE Robert T. Vigus Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2013 APPROVED: Guy Chet, Committee Co-Chair Christopher Fuhrmann, Committee Co-Chair Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Vigus, Robert T. Fortification Renaissance: The Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne. Master of Arts (History), May 2013, pp.71, 35 illustrations, bibliography, 67 titles. The Military Revolution thesis posited by Michael Roberts and expanded upon by Geoffrey Parker places the trace italienne style of fortification of the early modern period as something that is a novel creation, borne out of the minds of Renaissance geniuses. Research shows, however, that the key component of the trace italienne, the angled bastion, has its roots in Greek and Roman writing, and in extant constructions by Roman and Byzantine engineers. The angled bastion of the trace italienne was yet another aspect of the resurgent Greek and Roman culture characteristic of the Renaissance along with the traditions of medicine, mathematics, and science. The writings of the ancients were bolstered by physical examples located in important trading and pilgrimage routes. Furthermore, the geometric layout of the trace italienne stems from Ottoman fortifications that preceded it by at least two hundred years. The Renaissance geniuses combined ancient bastion designs with eastern geometry to match a burgeoning threat in the rising power of the siege cannon. Copyright 2013 by Robert T. Vigus ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and encouragement of many people. -

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001 Weekly Report 2 — August 18, 2014 Michael D. Danti Heritage Timeline August 16 APSA website released a video and a short report on alleged looting at Deir Turmanin (5th Century AD) in Idlib Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-018. • DGAM posted a report on alleged vandalism/looting and combat damage sustained to the Roman/Byzantine Beit Hariri (var. Zain al-Abdeen Palace) of the 2nd Century AD in Inkhil, Daraa Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-017. • Heritage for Peace released its weekly report Damage to Syria’s Heritage 17 August 2014. August 15 DGAM posts short report Burning of the Historic Noria Gaabariyya in Hama. Cf. SHI Incident Report SHI14-006 dated Aug. 9. DGAM report provides new photos of the fire damage. SHI Report Update SHI14-006. August 14 Chasing Aphrodite website posted an article entitled Twenty Percent: ISIS “Khums” Tax on Archaeological Loot Fuels the Conflicts in Syria and Iraq featuring an interview between CA’s Jason Felch and Dr. Amr al-Azm of Shawnee State University. • Damage to a 6th century mosaic from al-Firkiya in the Maarat al-Numaan Museum. Source: Smithsonian Newsdesk report. SHI Incident Report SHI14-016. • Aleppo Archaeology website posted a video showing damage in the area south of the Aleppo Citadel — much of the damage was caused by the July 29 tunnel bombing of the Serail by the Islamic Front. https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=739634902761700&set=vb.4596681774 25042&type=2&theater SHI Incident Report Update SHI14-004.