The Lindisfarne Gospels: Aldred's Gloss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of the Book of Kells: Two Masters and Two Campaigns

The making of the Book of Kells: two Masters and two Campaigns Vol. I - Text and Illustrations Donncha MacGabhann PhD Thesis - 2015 Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London 1 Declaration: I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at any other university, and that it is entirely my own work. _________________________________ Donncha MacGabhann 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the number of individuals involved in the making of the Book of Kells. It demonstrates that only two individuals, identified as the Scribe-Artist and the Master-Artist, were involved in its creation. It also demonstrates that the script is the work of a single individual - the Scribe-Artist. More specific questions are answered regarding the working relationships between the book’s creators and the sequence of production. This thesis also demonstrates that the manuscript was created over two separate campaigns of work. The comprehensive nature of this study focuses on all aspects of the manuscript including, script, initials, display-lettering, decoration and illumination. The first part of chapter one outlines the main questions addressed in this thesis. This is followed by a summary of the main conclusions and ends with a summary of the chapter- structure. The second part of chapter one presents a literature review and the final section outlines the methodologies used in the research. Chapter two is devoted to the script and illumination of the canon tables. The resolution of a number of problematic issues within this series of tables in Kells is essential to an understanding of the creation of the manuscript and the roles played by the individuals involved. -

The Texts of the Lindisfarne Gospels

chapter 10 The Texts of the Lindisfarne Gospels Richard Marsden Beneath its celebratory splendour, the Lindisfarne Gospels associating production of the gospel-book with the cult of is a text – or rather texts. What we encounter today, after St Cuthbert has no foundation in evidence, and the earli- the addition of an Old English translation above the Latin est reference to its origins, in the above-mentioned colo- text more than two centuries after the original copying, is phon, makes no reference to Cuthbert at all.2 The work is a bilingual gospel-book. As such, it is an unusually rich said there to have been dedicated simply to the ‘holy ones’ resource for historians of both text and language; but the (Old English halgum, saints or possibly the community processes of trying to assess the two texts and to under- itself) of Lindisfarne. Thus the year of St Cuthbert’s trans- stand the relationship between them are hampered by lation (698) and the launch of his cult are no longer neces- many anomalies and puzzles. Some of these derive from sary reference points in our conjectures about when the instabilities which are inherent in Bible texts (in Eadfrith copied out the gospels. Although some recent whatever language) in the medieval period, some are a estimates have stretched the likely period of copying consequence of the vagaries and accidents of manuscript towards the end of Eadfrith’s life, Gameson’s argument transmission, and some reflect the complex dynamics of that by 710 the bishop would have been too elderly to be the glossing process itself. -

St Cuthbert Story

Cuthbert was born about the year 634 (about 1400 years ago!) He lived in Melrose in Southern Scotland. He liked to walk in the hills. One night, when he was helping to look after sheep he thought he saw angels taking a soul to heaven. A few days later he found out Saint Aidan had died. Cuthbert decided to become a monk. He became a monk at the monastery in Melrose where he met Boisil, the prior of the monastery. Boisil taught Cuthbert for 6 years. Before Boisil died, he told Cuthbert he would be a Bishop one day. Cuthbert liked to visit lonely farms and villages. Crowds of people came to visit him. He lived at Melrose monastery for 13 years. Cuthbert was sent to be Prior of Lindisfarne. Cuthbert taught the monks the new Roman church rules. Some of the monks did not like the new rules and Cuthbert had to be very patient with them. After 12 years, Cuthbert went to live on a quiet island 7 miles away from Lindisfarne. Cuthbert lived on this small island for 3 years. He grew barley and vegetables and his monks dug a well and built a guest house for visitors. The King asked Cuthbert to be Bishop of Hexham. Cuthbert didn’t want to but he still remembered what Boisil had said. Cuthbert did not want to be Bishop of Hexham but agreed to be Bishop of Lindisfarne instead. He was very sad to have to leave his small island. Cuthbert was Bishop of Lindisfarne for 2 years. The people loved him. -

The Lindisfarne Gospels

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Special Issue 03 | Winter 2014 http://www.forumjournal.org Title The Lindisfarne Gospels: A Living Manuscript Author Margaret Walker Publication FORUM: University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue Number Special Issue 03 Issue Date Winter 2014 Publication Date 20/01/2014 Editors Victoria Anker & Laura Chapot FORUM claims non-exclusive rights to reproduce this article electronically (in full or in part) and to publish this work in any such media current or later developed. The author retains all rights, including the right to be identified as the author wherever and whenever this article is published, and the right to use all or part of the article and abstracts, with or without revision or modification in compilations or other publications. Any latter publication shall recognise FORUM as the original publisher. FORUM | SPECIAL ISSUE 03 Walker 1 The Lindisfarne Gospels: A Living Manuscript Margaret Walker The University of Edinburgh This article questions how current and previous owners have marked the Lindisfarne Gospels, created 1,300 years ago. Their edits, which would be frowned upon today, are useful for historians to understand how the Gospels have been valued by previous owners and thus why they are so treasured today. The Lindisfarne Gospels are on display in the treasures gallery of the British Library. The eighth- century Insular manuscript is opened and accompanied by a short caption with information about the work. i It is presented as a 1,300-year-old masterpiece, which has survived to the present day against the odds of time. -

The Venerable Bede a Celebration

The Venerable Bede A Celebration Monday 25 May 2020 5.15 p.m. The Venerable Bede Bede served in the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow for all his life, and died in Jarrow in 735 aged about 62. In 1020, his body was brought to Durham to be placed with the body of St Cuthbert. Bede’s body was brought to its final resting place in the Galilee Chapel in 1370. Introit Christ is the Morning Star Christ is the Morning Star who when the night of this world is past brings to his saints the promise of the light of life and opens everlasting day. Alleluia. The Venerable Bede Richard Lloyd The Dean welcomes the people Hymn We sing to God in praise of Bede (tune NEH 431) We sing to God in praise of Bede, The prince of scholars in his age, Christ’s servant, lover of God’s word, Once monk of Jarrow, priest and sage. For his example we give thanks, His zeal to learn, his skill to write; Like him we long to know God’s ways And in God’s word drink with delight. Grant us, good Lord, one day to come To you, all wisdom’s fountainhead, With Bede to stand before your face, Our Saviour, living from the dead. Teach us, O Lord, like Bede to pray, To make the word of God our joy, Exult in music, song and art, In worship all your gifts employ. O Christ, our glorious Morning Star, Come with the passing of the night, Bring to your saints th’eternal day, The promise of your life and light. -

The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-Writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250

Quidditas Volume 29 Article 4 2008 The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250 John D. Young Flagler College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Young, John D. (2008) "The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250," Quidditas: Vol. 29 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol29/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 26 Quidditas The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250 John D. Young Flagler College This paper describes the use of the cult of Saint Cuthbert in the High Middle Ages by both the bishops of Durham and the Benedictine community that was tied to the Episcopal see. Its central contention is that the churchmen of Durham adapted this popular cult to the political expediencies of the time. In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, when Bishop William de St. Calais ousted the entrenched remnants of the Lindisfarne community and replaced them with Benedictines, Cuthbert was primarily a monastic saint and not, as he would become, a popular pilgrimage saint. However, once the Benedictine community was firmly entrenched in Durham, the bishops, most prominently Hugh de Puiset, sought to create a saint who would appeal to a wide audience of pilgrims, including the women who had been excluded from direct worship in the earlier, Benedictine version of the saint. -

Book Burning and Censorship

THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS 0. THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS - Story Preface 1. WHY FREE EXPRESSION? 2. FREE EXPRESSION IN BOOKS 3. THE DIAMOND SUTRA 4. THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS 5. THE PRECIOUS MANUSCRIPTS 6. JOHN WYCLIFFE'S BOOKS 7. JOHN HUS BURNS 8. TYNDALE WRITES, THEN BURNS 9. LUTHER'S TRANSLATIONS ARE BURNED 10. THE PRINTING PRESS 11. BOOKS BURN IN THE NEW WORLD 12. CENSORSHIP CONTINUES 13. BURNING CONTINUES 14. CHERISHED RIGHTS 15. MORE COOL LINKS Folio 27r of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Depicted here is the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew. Image online via Wikimedia Commons. Today we can examine the work of one monk, Eadrith (later the Bishop of Lindisfarne), who produced a stunning example of book painting that is even older than the Diamond Sutra. Although the manuscript is undated, The Lindisfarne Gospels were likely copied and illustrated by Eadrith while he was still a monk at Lindisfarne Priory, on Holy Island (off the English Northumberland coast). Nothing remains of the original monastery. Since Eadrith became Bishop in 698 AD—the date scholars typically use forthe manuscript—St. Bilfrid bound the manuscript and added precious gems and metalwork to its binding. Currently owned by the British Library, the Lindisfarne Gospels contain notes from a priest, Aldred, who also inserted a word-for-word Anglo-Saxon translation in the spaces between the lines of Latin text. Those insertions were probably made between 950 and 970 AD. In the meantime, the monks had fled looting Vikings who, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, invaded the area (be sure to activate "fly" to "view" this virtual-tour animation) duringJanuary of 793. -

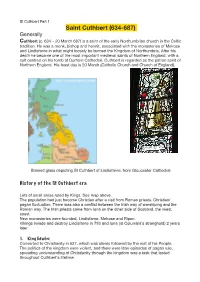

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (C

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (c. 634 – 20 March 687) is a saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in what might loosely be termed the Kingdom of Northumbria. After his death he became one of the most important medieval saints of Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert is regarded as the patron saint of Northern England. His feast day is 20 March (Catholic Church and Church of England), Stained glass depicting St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, from Gloucester Cathedral History of the St Cuthbert era Lots of small areas ruled by Kings. See map above. The population had just become Christian after a visit from Roman priests. Christian/ pagan fluctuation. There was also a conflict between the Irish way of worshiping and the Roman way. The Irish priests came from Iona on the other side of Scotland, the /west coast. New monasteries were founded, Lindisfarne, Melrose and Ripon. Vikings invade and destroy Lindisfarne in 793 and Iona (st Columbia’s stronghold) 2 years later. 1. King Edwin: Converted to Christianity in 627, which was slowly followed by the rest of his People. The politics of the kingdom were violent, and there were later episodes of pagan rule, spreading understanding of Christianity through the kingdom was a task that lasted throughout Cuthbert's lifetime. Edwin had been baptised by Paulinus of York, an Italian who had come with the Gregorian mission from Rome. -

69-19,257 STOLTZ, Linda Elizabeth, 1938- the DEVELOPMENT OF

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LEGEND OF ST. CUTHBERT Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stoltz, Linda Elizabeth, 1938- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:02:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/287860 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-19,257 STOLTZ, Linda Elizabeth, 1938- THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LEGEND OF ST. CUTHBERT. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE DEVELOPMENT OP THE LEGEND OP ST. CUTHBERT by Linda Elizabeth Stoltz A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Linda Elizabeth Stoltz entitled The Development of the Legend of St. Cuthbert be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy LSIL jf/r. / /9/9 Disseycation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:-• Z- y£~ ir ApJ /9S? $ Lin— • /5 l*L°l ^ ^7^ /(, if6? C^u2a,si*-> /4 /f(?,7 . -

Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture

139 4 Assembling and reshaping Christianity in the Lives of St Cuthbert and Lindisfarne Gospels In the previous chapter on the Franks Casket, I started to think about the way in which a thing might act as an assembly, gather- ing diverse elements into a distinct whole, and argued that organic whalebone plays an ongoing role, across time, in this assemblage. This chapter begins by moving the focus from an animal body (the whale) to a human (saintly) body. While saints, in early medieval Christian thought, might be understood as special and powerful kinds of human being – closer to God and his angels in the heavenly hierarchy and capable of interceding between the divine kingdom and the fallen world of mankind – they were certainly not abstract otherworldly spirits. Saints were embodied beings, both in life and after death, when they remained physically present and accessible through their relics, whether a bone, a lock of hair, a fingernail, textiles, a preaching cross, a comb, a shoe. As such, their miracu- lous healing powers could be received by ordinary men, women and children by sight, sound, touch, even smell or taste. Given that they did not simply exist ‘up there’ in heaven but maintained an embodied presence on earth, early medieval saints came to be asso- ciated with very particular places, peoples and landscapes, with built and natural environments, with certain body parts, materi- als, artefacts, sometimes animals. Of the earliest English saints, St Cuthbert is probably one of, if not the, best known and even today remains inextricably linked to the north-east of the country, especially the Holy Island of Lindisfarne and its flora and fauna. -

St. Dunstan School May 2017

V St. Dunstan School May 2017 Principal L. O’Neill Secretary S. Oh Trustee Luz del Rosario 416.528.6447 Prayer For May Superintendent Deb Finegan-Downey Loving God, 905.890.1221 In Mary You have given Parish St. Joseph Church Your church a sign of the glory to come. 5440 Durie Road May those who honour the Virgin Mother Mississauga, ON L5M 2J6 look to her as a model of holiness for all 905.826.2766 Your people. School Hours We ask this through Christ our Lord. Grades FDK-8 Amen 8:30-11:25 & 12:25 - 3:00 St. Dunstan School 1525 Cuthbert Ave. Mississauga, ON L5M 3R6 905.567.5050 http://www.dpcdsb.org/ DUNST May is the month we dedicate to Mary, the mother of our Saviour, Jesus. We celebrate Mary, who humbly and gladly accepted God’s will when she said “Yes” to our Lord. As Twitter @dunstandolphins we honour Mary and all mothers, we are reminded of the many blessing mothers bestow upon their children each and every day. Let us keep Mary and all mothers in our thoughts and prayers so that the honour and respect they deserve is not limited to one day or month in the year. We begin the month of May with Catholic Education Week, which is recognized throughout Ontario during the week of April 30 - May 5. During this week, the Catholic community celebrates the unique and distinctive contribution that Catholic schools make to our students, our community and our province. Catholic Education Week is a welcome opportunity to celebrate the mission of our Catholic schools as they strive to integrate the Gospel values of Jesus Christ in every aspect of the school’s life and curriculum. -

Stereoscopic Comparison As the Long-Lost Secret to Microscopically Detailed Illumination Like the Book of Kells'

Perception, 2009, volume 38, pages 1087 ^ 1103 doi:10.1068/p6311 Stereoscopic comparison as the long-lost secret to microscopically detailed illumination like the Book of Kells' John L Cisne Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Received 19 October 2008, in revised form 15 January 2009; published online 17 July 2009 Abstract. The idea that the seventh- and eighth-century illuminators of the finest few Insular manuscripts had a working knowledge of stereoscopic images (otherwise an eighteenth- and nineteenth-century discovery) helps explain how they could create singularly intricate, micro- scopically detailed designs at least five centuries before the earliest known artificial lenses of even spectacle quality. An important clue to this long-standing problem is that interlace patterns drawn largely freehand in lines spaced as closely as several per millimeter repeat so exactly across whole pages that repetitions can be free-fused to form microscopically detailed stereo- scopic images whose relief in some instances indicates precision unsurpassed in astronomical instruments until the Renaissance. Spacings between repetitions commonly harmonize closely enough with normal interpupillary distances that copying disparities can be magnified tens of times in the stereoscopic relief of the images. The proposed explanation: to copy a design, create a pattern, or perfect a design's template, the finest illuminators worked by successive approximation, using their presumably unaided eyes first as a camera lucida to fill a measured grid with multiple copies from a design, and then as a stereocomparator to detect and minimize disparities between repetitions by minimizing the relief of stereoscopic images, in the manner of a Howard ^ Dolman stereoacuity test done in reverse.