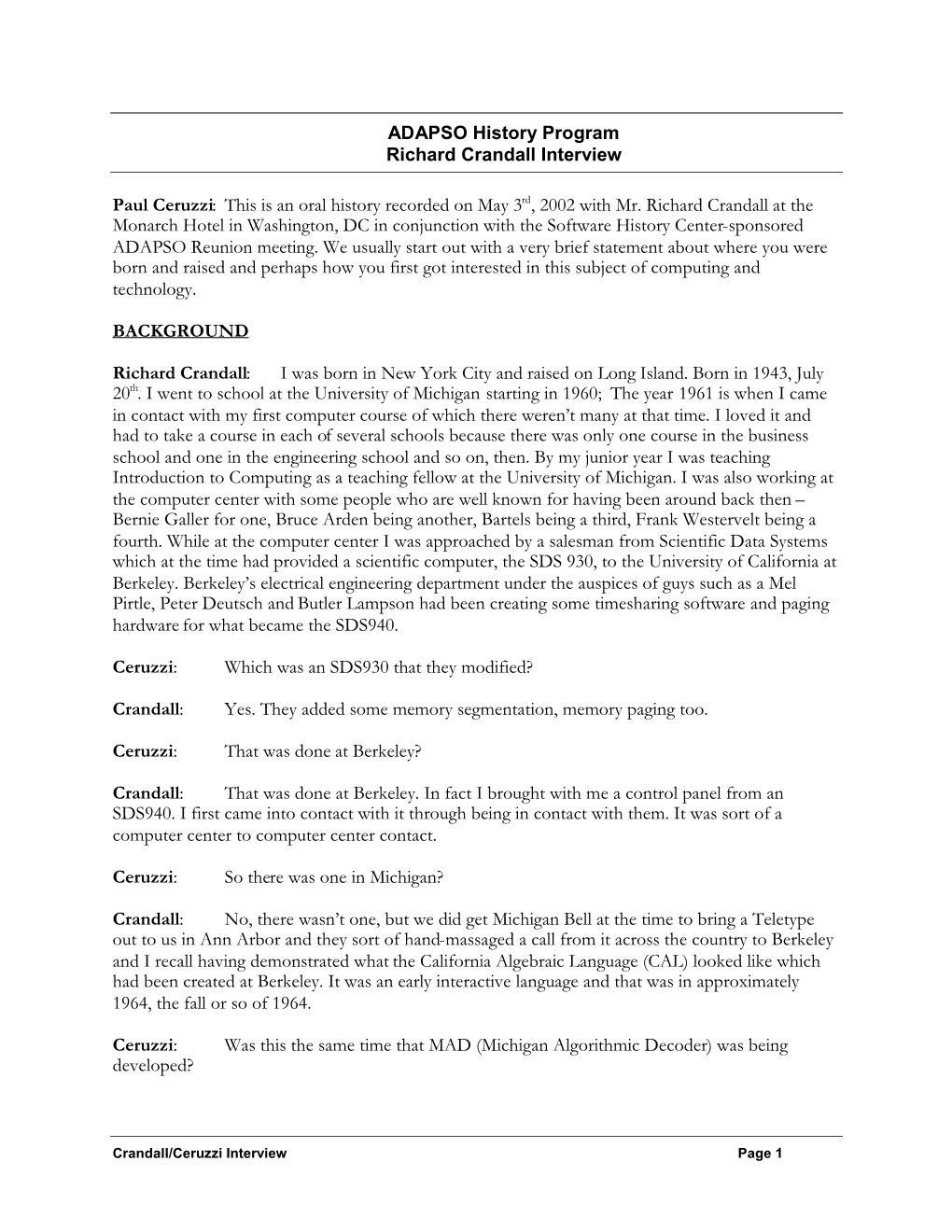

ADAPSO History Program Richard Crandall Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Bernard A. Galler

An Interview with BERNARD A. GALLER OH 236 Conducted by Enid H. Galler on 8, 10-11, and 16 August 1991 Sutton's Bay, MI Ann Arbor, MI Charles Babbage Institute Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute 1 Bernard A. Galler Interview 8, 10-11, and 16 August 1991 Abstract In this wide-ranging interview, Galler describes the development of computer science at the University of Michigan from the 1950s through the 1980s and discusses his own work in computer science. Prominent subjects in Galler's description of his work at Michigan include: his arrival and classes with John Carr, research use of International Business Machines (IBM) and later Amdahl mainframe computers, the establishment of the Statistical Laboratory in the Mathematics Dept., the origin of the computer science curriculum and the Computer Science Dept. in the 1950s, interactions with Massachusetts Institute of Technology and IBM about timesharing in the 1960s, the development of the Michigan Algorithm Decoder, and the founding of the MERIT network. Galler also discusses Michigan's relationship with ARPANET, CSNET, and BITNET. He describes the atmosphere on campus in the 1960s and early 1970s and his various administrative roles at the university. Galler discusses his involvement with the Association for Computing Machinery, the American Federation of Information Processing Societies, the founding of the Charles Babbage Institute, and his work with the Annals of the History of Computing. He describes his consultative work with Israel and his consulting practice in general, his work as an expert witness, and his interaction with the Patent Office on issues surrounding the patenting of software and his role in the establishment of the Software Patent Institute. -

MTS on Wikipedia Snapshot Taken 9 January 2011

MTS on Wikipedia Snapshot taken 9 January 2011 PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 09 Jan 2011 13:08:01 UTC Contents Articles Michigan Terminal System 1 MTS system architecture 17 IBM System/360 Model 67 40 MAD programming language 46 UBC PLUS 55 Micro DBMS 57 Bruce Arden 58 Bernard Galler 59 TSS/360 60 References Article Sources and Contributors 64 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 65 Article Licenses License 66 Michigan Terminal System 1 Michigan Terminal System The MTS welcome screen as seen through a 3270 terminal emulator. Company / developer University of Michigan and 7 other universities in the U.S., Canada, and the UK Programmed in various languages, mostly 360/370 Assembler Working state Historic Initial release 1967 Latest stable release 6.0 / 1988 (final) Available language(s) English Available programming Assembler, FORTRAN, PL/I, PLUS, ALGOL W, Pascal, C, LISP, SNOBOL4, COBOL, PL360, languages(s) MAD/I, GOM (Good Old Mad), APL, and many more Supported platforms IBM S/360-67, IBM S/370 and successors History of IBM mainframe operating systems On early mainframe computers: • GM OS & GM-NAA I/O 1955 • BESYS 1957 • UMES 1958 • SOS 1959 • IBSYS 1960 • CTSS 1961 On S/360 and successors: • BOS/360 1965 • TOS/360 1965 • TSS/360 1967 • MTS 1967 • ORVYL 1967 • MUSIC 1972 • MUSIC/SP 1985 • DOS/360 and successors 1966 • DOS/VS 1972 • DOS/VSE 1980s • VSE/SP late 1980s • VSE/ESA 1991 • z/VSE 2005 Michigan Terminal System 2 • OS/360 and successors -

Computing at the University of Michigan: the Early Years, Through the 1960’S”

n a display case in the Lurie Engineering Center of the University of Professor Emeritus Norman R. Michigan’s College of Engineering, an example of advanced computing Scott joined the Department technology of the early 20th century, a cylindrical slide rule can be seen. It of Electrical Engineering at the consists of two coaxial cylinders 18 inches long, carrying segments of a 30-foot slide University of Michigan in 1951 rule, mounted so that they can be rotated independently and moved axially relative to and retired from the Depart- ment of Electrical Engineering each other. It is a Keuffel and Esser product, model 4012, and the instruction manual and Computer Science (EECS) in refers to it as “Thacher’s Calculating Instrument, for performing a great variety of useful 1988. He was actively involved in calculations with unexampled rapidity and accuracy, cylinder 18” in polished Mahogany the early days of computing at Box with Directions — each $35.00.” Michigan, including teaching one The preface of the manual says, “— With the Thacher Calculating Instrument — the of the first courses on analog and scales are 30 feet long so that they will give results correctly to four and usually five digital computer technology in places of figures, sufficient to satisfy nearly every requirement of the professional and 1954, and completing much of the design work for the Michigan business man. — By the use of this instrument, the drudgery of calculation is avoided, Instructional Computer (MIC) in and the relief to the mind may be compared with the most improved mechanical 1955. He became a fellow of the devices in overcoming the wear and tear of manual labor.”1 IEEE in 1965. -

Ed 149 727 Title Pub Date

a 4 DOCUMINT41ESOBEr) ED 149 727 , IR 005,504 . - TITLE AbstriOti of Research. 'July 1974-June 1975'. INSTITUTION Ohio. State, Univ.c'Cblumbus. Computer and Information Science Research Center. PUB DATE '75 :NOTE 92p.; For related documents, se ED 092 117, ED 097 .' 025, ED 139 394 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC -$4.67 Plus Postage._ DESCRIPTORS *Abstracts; *Annual 'Reports; Artificial intelligence; Cognitive Provesses; Computational Linguistics; *Computer Programs; *Compqter Science; Information Processing; Ibformaticn Retrieval; *Informati?n . Science; Information Storage ABSTRACT Abstracts'of research papers in computer and . information science aie given for 68papers in the areas cf information storage and retrieval; human informationprocessing; information analysis; linguistic analysis; artificialintelligence; information processes in physical, biclogicalpand socialsystems; mathematical techniques; systems programming; computerarchitecture and networks; joint programs; and computation theory.Abstracts are indexed by investigator and subject. Introductory materialincludes a -description of the Ohio State University Computer andInformation Science Research Center. (VT) - r S. ***************v*******4***************************4****************** Reproductions'eproductions Supplied by Eptts are the best that can be made * froi the original document.- * ***********************************************************************- * wt. U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. x ..,1411, 'EDUCATION t WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF I EDUCATION, iff:,-;e4ey'hi.S.tWral.' -

Directorate for Mathematical and Physical REPORT NO' *Artificial

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 943 SE 045 918 TITLE Division of Computer Research Summary of Awards, Fiscal Year 1984. INSTITUTION National Science Foundation, Washington, DC. Directorate for Mathematical and Physical Sciences. REPORT NO' NSF-84-77 PUB DATE 84 NOTE 93p. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Pigs Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Artificial Intelligence; *Computer Oriented Programs; *Computers; *Computer Science; Databases; *Grants; Higher Education; Mathematics; Program Descriptions IDENTIFIERS National Science Foundation ABSTRACT Provided in this report are summaries of grants awarded by the National Science Foundation Division of Computer Research in fiscal year 1984. Similar areas of research are grouped (for the purposes of this report only) into these major categories: (1) computational mathematics; (2) computer systems design; (3) intelligent systems;(4) software engineering; (5) software systems science; (6) special projects, such as database management, computer-based modeling, and privacy and security of computer systems; (7) theoretical computer science; (8) computer research equipment; and (9) coordinated experimental research. Also included are presidential young investigator awards and awards for small business innovation research. Within each category, awards are listed alphabetically by state and institution. Each entry includes the grantee institution, name of the principal investigator(s), project title, award identification number, award amount, award duration, and desCription. (This report lists fewer -

Celebrating 50 Years of Campus-Wide Computing

Celebrating 50 Years of Campus-wide Computing The IBM System/360-67 and the Michigan Terminal System 13:30–17:00 Thursday 13 June 2019 Event Space, Urban Sciences Building, Newcastle Helix Jointly organised by the School of Computing and the IT Service (NUIT) School of Computing and IT Service The History of Computing at Newcastle University Thursday 13th June 2019, 13:30 Event Space, Urban Sciences Building, Newcastle Helix, NE4 5TG Souvenir Collection Celebrating 50 Years of Campus-wide Computing – 2019 NUMAC and the IBM System/360-67 – 2019 NUMAC Inauguration – 1968 IBM System/360 Model 67 (Wikipedia) The Michigan Terminal System (Wikipedia) Program and Addressing Structure in a Time-Sharing Environment et al – 1966 Virtual Memory (Wikipedia) Extracts from the Directors’ Reports – 1965-1989 The Personal Computer Revolution – 2019 Roger Broughton – 2017 Newcastle University Celebrating 50 Years of Campus-wide Computing The IBM System/360-67 and the Michigan Terminal System 13:30–17:00 Thursday 13 June 2019 Event Space, Urban Sciences Building, Newcastle Helix Jointly organised by the School of Computing, and the IT Service Two of the most significant developments in the 65 year history of computing at Newcastle University were the acquisition of a giant IBM System/360-67 mainframe computer in 1967, and subsequently the adoption of the Michigan Terminal System. MTS was the operating system which enabled the full potential of the Model 67 – a variant member of the System/360 Series, the first to be equipped with the sort of memory paging facilities that years later were incorporated in all IBM’s computers – to be realized. -

ABDOU YOUSSEF Department of Computer Science

ABDOU YOUSSEF Department of Computer Science The George Washington University Washington, DC 20052 Tel: 202-994-4953, Fax: 202-994-4875 E-mail: [email protected] Citizenship USA Education - Ph.D. in Computer Science Princeton University 2/88 - M.A. in Computer Science Princeton University 6/85 - B.S. in Mathematics The Lebanese University 10/81 Academic - The George Washington University Experience Department of Computer Science o Department Chairman 7/1/08-6/30/14 o Professor 6/99-present o Associate Professor 9/93-6/99 o Assistant Professor 9/87-8/93 - National Institute of Standards and Technology 9/94-present Intermittent Faculty Appointment, Computer Scientist - The Johns Hopkins University 9/95-6/95 Visiting Faculty - Princeton University 9/84-8/87 Research/Teaching Assistant - The Lebanese University 9/81-9/82 Lecturer Research Applications of Data Science and NLP, Math Search and Math NLP Interests Image/Video Processing, Parallel Processing, Algorithms Awards - Gold Medal from the US Department of Commerce 12/2011 - Co-recipient of the 2011 Government Computer News Award for Outstanding Information Technology Achievement 2011 - Six-time winner of the best-teacher-of-the-year award 95, 97, 98, 99, 04, 09 The George Washington University - Teaching/Research Assistantship Princeton University 1984-87 - A Merit Scholarship for a Ph.D. degree The Lebanese University 1983-87 Professional - Senior Member of IEEE Societies - Member of IEEE Computer Society 1 Courses Taught: Data Compression (Graduate) Algorithms (Graduate) Discrete Mathematics (Undergraduate) Automata and Formal Languages (Graduate and Undergraduate) Object-oriented Programming (Undergraduate) Data Structures (Graduate and Undergraduate) Advanced Data Structures (Graduate) Advanced Computer Architecture (Advanced Graduate) Parallel Algorithms (Advanced Graduate) Parallel Processing (Advanced Graduate) Digital Libraries (Advanced Graduate) Number of Supervised Ph.D. -

Computer-Based National Information Systems: Technology and Public Policy Issues

Computer-Based National Information Systems: Technology and Public Policy Issues September 1981 NTIS order #PB82-126681 9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 81-600144 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword This report presents the results of an overview study on the use of computer technology in national information systems and related public policy issues. The purposes of this study are: ● To provide a general introduction to computer-based national in forma- tion systems. –Will help acquaint the nonexpert reader with the nature of computer-based national information systems and the role they play in American society. ● To provide a framework for understanding computer and information policy issues. —Develops a structure of information policy and presents brief essays on several of the more important issue areas, with an em- phasis on how future applications of computer-based information systems may intensify or alter the character of the policy debate and the need for new or revised laws and policies. ● To provide a state-of-the-art survey of computer and related technologies and industries. –Highlights recent developments in computer and in- formation technologies and describes the current status and likely evolu- tion of the computer and information industries. ● To Provide a foundation for other related studies. While some observa- tions can be made about national information systems in general, a full assessment of impacts and issues is best conducted in the context of specific systems. The report builds a foundation for three related OTA studies in the areas of computerized criminal history records, electronic mail, and electronic funds transfer. -

Programmatic Coverage of Computer Science Topics Within the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology of the National Bureau of Standards

NBSIR 75-753(^1?) Programmatic Coverage of Computer Science Topics Within the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology of the National Bureau of Standards Joseph 0. Harrison, Jr. Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology National Bureau of Standards Washington, D. C. 20234 June, 1975 Final Report U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS NBSIR 75-753 PROGRAMMATIC COVERAGE OF COMPUTER SCIENCE TOPICS WITHIN THE INSTITUTE FOR COMPUTER SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY OF THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS Joseph 0. Harrison, Jr. Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology National Bureau of Standards Washington, D. C. 20234 June, 1975 Final Report U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Rogers C.B. Morton, Secretary John K. Tabor, Under Secretary Dr. Betsy Ancker-Johnson, Assistant Secretary for Science and Technology NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDAPtOS, Ernest Ambler, Acting Director FOREWORD The material in this paper is taken from two reports on computer science in ICST submitted to the Director, ICST, Dr. Ruth M. Davis in April 1975. This report will serve to make it available to the NBS staff. In compiling the material a number of prominent members of the academic community were interviewed regarding their views on a definition of computer science. In particular, discussions were held with the following persons: Dr. Bruce Arden Princeton University and Principal Investigator of NSF Study to Classify Computer Science Dr. William F. Atchison National Institute of Education Program for Productivity and Technology Former Chairman of the ACM Curriculum Committee That Developed ACM Curriculum 68 Dr. Richard Austing University of Maryland and Chairman of ACM SIGCSE Under Whose Auspices ACM Curriculum 68 Is Being Revised Dr. -

An Undergraduate Computer Engineering Option for Electrical Engineering

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 062 134 SE 013 544 TITLE An Undergraduate Computer Engineering Option for Electrical Engineering. INSTITUTION National Academy of Engineering, Washing on, D.C. Commission on Education. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Was ington, D.C. PUB DATE Jan 70 NOTE 13p AVAILABLE FROMCom iss on on Education, National Academy of Engineering, 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20418 (Free) EDPS _RICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3,29 DESCRIPTORS College Science; Computer Science; puter Science Education; *Curriculum Development; Engineering Education; *Program Content; Program Descriptions; Undergraduate Study ABS1RACT This report is the result of a study, funded by the National Science Foundation, of a group constituted as the COSINE Task Force on Undergraduate Education in Computer Engineering in 1969. The group was formel in response to the growing demand for education in computer engineering and the limited opportunitier" for study in this area. Computer engineering is concerned with the organization, design, and utilization of digital processin systems as general purpose computers or as components of systems concerned with communication, control: measurement, or signal processing. The report is concerned with d new undergraduate option within electrical engineering which is called "computer engineering" and considers the need for such a program, a description of its content, and a plan of implementation. Included are recommended subjects, electives and prerequisites for computer engineering prograga. Possible four year computer engineering curricula within electricai engineering are presented as developed by four universities: Carnegia-Mellon, Princeton, The Univer ity of Texas at Austin, and University of Hawaii. (Author/TS) An Undergraduate January 1970 Computer Engineering U.S. -

Oral History Interview with Allen Newell

An Interview with ALLEN NEWELL OH 227 Conducted by Arthur L. Norberg on 10-12 June 1991 Pittsburgh, PA Charles Babbage Institute Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute 1 Allen Newell Interview 10-12 June 1991 Abstract Newell discusses his entry into computer science, funding for computer science departments and research, the development of the Computer Science Department at Carnegie Mellon University, and the growth of the computer science and artificial intelligence research communities. Newell describes his introduction to computers through his interest in organizational theory and work with Herb Simon and the Rand Corporation. He discusses early funding of university computer research through the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Mental Health. He recounts the creation of the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) under J. C. R. Licklider. Newell recalls the formation of the Computer Science Department at Carnegie Mellon and the work of Alan J. Perlis and Raj Reddy. He describes the early funding initiatives of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) and the work of Burt Green, Robert Cooper, and Joseph Traub. Newell discusses George Heilmeier's attempts to cut back artificial intelligence, especially speech recognition, research. He compares research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and Computer Science Department with work done at Carnegie Mellon. Newell concludes the interview with a discussion of the creation of the ARPANET and a description of the involvement of the research community in influencing ARPA personnel and initiatives. 2 ALLEN NEWELL INTERVIEW DATE: 10 June 1991 INTERVIEWER: Arthur L. -

19880006972.Pdf

- NASA Contractor Rcpcm 181607 .- ICASE SEMIANNUAL REPORT April 1, 1987 through October 1, 1987 Contract NO. NASl-18107 December 1987 (AASA-CR-l&lbL7) [ BEStABCE 11 €GCGGESS 811 Ned-16354 'IkE INS'I15IOIE PC& CCE€LTEL dEILI<AIIOIS XZE ECIEbCE ABC ELGJ bEEEIbG 3 SE&iaLtlual Report, 1 AFE, 4 Octo 1St27 E2 121 - (NASA) F CSCL 63/59 Unclas0121842 INSTITUTE FOR COMPUTER APPLICATIONS IN SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING NASA Langley Reaearch Center, Hampton, Virginia 23665 Operated by the Universities Space Research Association _- CONTENTS Page Introduction .............................................................. iii Research in Progress ...................................................... 1 Reports and Abstracts ..................................................... 39 ICASE colloquia...............................^... ........................ 58 ICASE Summer Activities ................................................... 61 Other Activities .......................................................... 66 ICASE Staff ............................................................... 67 i ~ INTRODUCTION The Institute for Computer Applications in Science and Engineering (ICASE) is operated at the bngley Research Center (LaRC) of NASA by the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) under a contract with the Center. USRA is a nonprofit consortium of major U. S. colleges and universities. The Institute conducts unclassified basic research in applied mathematics, numerical analysis, and computer science in order to extend and improve problewsolving