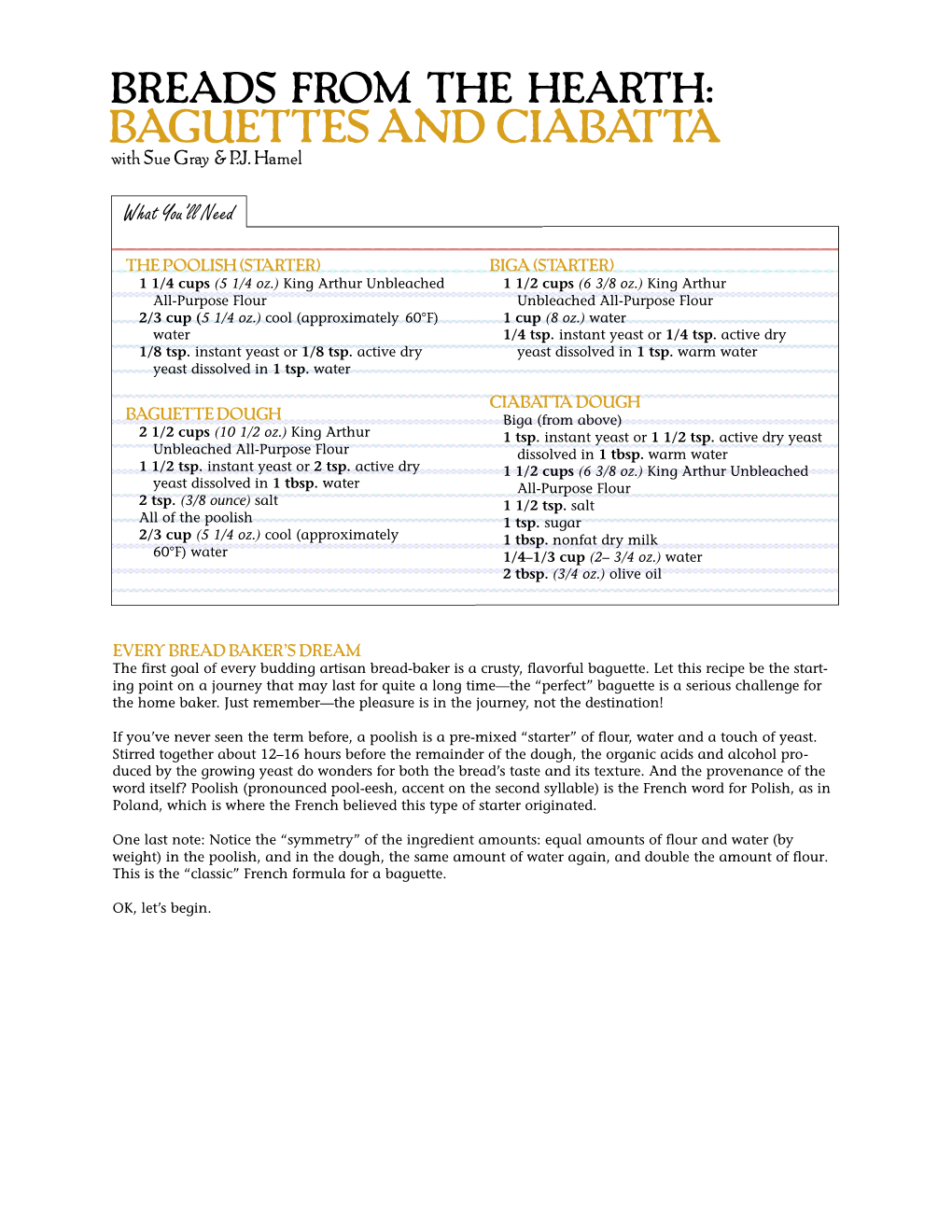

BAGUETTES and CIABATTA with Sue Gray & P.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Work with Our Customers to Develop the Products They Need. Over Time We Become a Trusted Partner, Not Just a Supplier.”

“We work with our customers to develop the products they need. Over time we become a trusted partner, not just a supplier.” /-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/ Our simple and honest approach to business has seen us gain numerous industry awards and achievements, yet we have no desire to grow much WELCOME TO bigger. Instead we wish to remain a small, friendly bakery, providing a personal service to those in London with a similar ethos of quality not FLOURISH quantity. We believe our success can be attributed to the fantastic products One of London’s we make alongside the great relationships we have developed with our staff, foremost independent suppliers and of course our customers. craft bakeries Whether you know us from our shops, the bakery, local farmer’s market or any of the fine restaurants or retailers that use our products, rest assured that you will be enjoying a world-class service and products created by master craftsmen using time-honored methods, natural ingredients, and baked in our traditional stone hearth ovens. Our bakery production runs 24 hours a day, 7 days per week. Our ovens never go cold, except for a few days over the Christmas and New Year’s period when we close to ensure our team take time out with their families. The product list that follows is merely a guide as to what we can make, if you have any specific requests or suggestions, please ask, we’ll endeavor to oblige (Minimum quantities will apply). – 1 – INTRODUCTION LONG FERMENTATION STAPLE LOAVES BUNS, BAPS AND ROLLS PASTRIES, TARTS AND SWEETS TS & CS Most breads use the same basic ingredients, flour, salt, yeast and water. -

Traditional Baguette

Team USA 2008 Formulas – contributed by Solveig Tofte TRADITIONAL BAGUETTE This is a fairly classic American baguette – FINAL DOUGH 40% of the flour goes into a poolish and : In the bowl of a spiral or vertical just 3% of the flour is used in a liquid planetary mixer with hook attachment, levain. The majority of the flavor comes place the poolish, levain and bread flour. from the poolish, and the small percentage : Adjust the water temperature for a OOD of levain brings a slightly more complex final dough temperature of 74°F. While W flavor from the wheat. The levain also adds mixing on first speed, add the water (this some strength and improves definition on dough shouldn’t be too soft). Mix for 2 the scores. minutes to incorporate and hydrate the ingredients. BRIAN PHOTO: The formula uses diastatic malted barley : Sprinkle the salt, yeast and malt powder flour to balance the high level of fermenta- over the top of the dough and autolyse tion in the formula. When prefermenting PROCess Preferments {poolish & levain} for 20 minutes. this much flour, the yeast has digested Mixing Type of mixer By hand : Mix on speed 1 for 2 minutes, adjusting most of the sugars before the final mix. hydration as needed. First fermentation Length 12 - 14 hours The enzyme activity provided by the malt : Mix on speed 2 to develop dough with Temperature 73°F will help extract additional sugars from the medium gluten development, about 45 Final dough starch in the flour, aiding in fermentation PROCess seconds. Mixing Type of mixer Spiral activity and coloration of the baguette in : Let the dough ferment in a covered Mix style Improved the oven. -

Organic Traditional Baguette Organic Rustic Baguette Organic Sesame Baguette Organic Sourdough Loaf Organic Multiseed Loaf Organ

MASON & GREENS BAKED GOODS ORGANIC TRADITIONAL BAGUETTE ORGANIC WHEAT FLOUR, ORGANIC SOURDOUGH STARTER, YEAST,SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT ORGANIC RUSTIC BAGUETTE ORGANIC WHEAT FLOUR, ORGANIC RYE FLOUR, ORGANIC WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, ORGANIC SOURDOUGH, SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT ORGANIC SESAME BAGUETTE ORGANIC WHEAT FLOUR, ORGANIC SESAME SEEDS, ORGANIC SOURDOUGH STARTER, YEAST, SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT ORGANIC SOURDOUGH LOAF ORGANIC WHITE FLOUR, ORGANIC SOURDOUGH STARTER, ORGANIC WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT ORGANIC MULTISEED LOAF ORGANIC WHITE FLOUR, ORGANIC SEEDS (ORGANIC ROLLED OATS, ORGANIC FLAXSEEDS, ORGANIC SESAME SEEDS, ORGANIC MILLET, ORGANIC SUNFLOWER SEEDS), ORGANIC SOURDOUGH STARTER, ORGANIC BARLEY, ORGANIC WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT ORGANIC WALNUT RAISIN LOAF ORGANIC WHITE FLOUR, ORGANIC SOURDOUGH STARTER, ORGANIC WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, ORGANIC SEEDLESS RAISINS, ORGANIC WALNUTS, ORGANIC STONE GROUND RYE FLOUR, SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT, WALNUT ORGANIC RUSTIC BOULE ORGANIC WHITE FLOUR, ORGANIC SOURDOUGH STARTER, ORGANIC WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, ORGANIC STONE GROUND RYE FLOUR, SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT OATMEAL RAISIN COOKIE WHEAT FLOUR, BROWN SUGAR, RAISIN, WHOLE GRAIN OAT, MARGARINE, COCONUT UNSWEETENED, MAPLE SYRUP, COCONUT MILK, CINNAMON, VANILLA EXTRACT, BAKING SODA, SEA SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT, SOYBEANS MORNING GLORY MUFFIN WHEAT FLOUR, SUGAR, CANOLA OIL, CARROT, BANANA, RAISINS, COCONUT, APPLE, CURACAO, VANILLA, CINNAMON, BAKINGPOWDER, CANDIED ORANGE, BAKING SODA, SALT, EGG SUBSTITUTE CONTAINS: WHEAT, COCONUT CRANBERRY VANILLA SCONE WHEAT FLOUR, COCONUT MILK, CRANBERRIES, COCONUT OIL, SUGAR, BAKING POWDER, VANILLA EXTRACT, SALT CONTAINS: WHEAT, COCONUT Copyright © 2020, Mason & Greens. All Rights Reserved. -

Gourmet Sandwiches

Gourmet Sandwiches American Combo $9.99 Ham, Turkey, Roast Beef, American Cheese, Lettuce And Tomato On A Hero Anchor $9.99 Fresh Turkey, Cranberry Sauce And Stuffing On 7 Grain Health Bread Cajun Style $9.99 Cajun Chicken, Pepper Jack Cheese, Grilled Red Peppers, Leaf Lettuce And Cilantro Chipotle Sauce On A Triangle Crispina Cambrie Style $9.99 Breaded Eggplant, Imported Provolone, Roasted Peppers And A Spinach And Artichoke Spread On Focaccia Chicken Blast $9.99 Breaded Chicken Cutlet, Fresh Mozzarella, Roasted Peppers, Sautéed Spinach And Sweet Pesto Sauce On Triangle Crispina Chicken Cutlet Melt $9.99 Breaded Chicken Cutlet, Bacon, Lettuce And Tomato With Your Choice Of Cheese And Dressing On A Toasted Hero Claudia’s Classic $9.99 Grilled Chicken, Avocado, Lettuce, Tomato, Red Onion And Balsamic Vinaigrette On A Toasted Hero Colby Beef Slam $9.99 Roast Beef, Colby Jack Cheese, Leaf Lettuce And Jalapeno Ranch Dressing On Tomato Focaccia Delightful Club $9.99 Smoked Turkey, Muenster Cheese, Avocado, Tomato, Romaine Lettuce And Russian Dressing On A Sesame Pumpernickel Club Gucci House $9.99 Herb Grilled Chicken, Fresh Mozzarella, Prosciutto, Mixed Greens And Roasted Sundried Tomato Spread On Focaccia Health Baguette $9.99 Marinated Grilled Chicken, Fresh Mozzarella, Sundried Tomatoes, Leaf Lettuce And Sweet Pesto Sauce On A 7 Grain Baguette Honey Maple Baguette $9.99 Honey Maple Turkey Breast, Brie Cheese And Sweet Roasted Almond Honey Mayo On A 7 Grain Baguette Horton Point $9.99 Grilled Roast Beef, Melted Mozzarella, Grilled Onions, -

French Bread Was Actually Created in Vienna

French Bread Was Actually Created In Vienna National French Bread Day is enjoyed by millions across the United States each year on March 21st. French bread, also known as a baguette, is a long thin loaf made from basic lean dough. It is defined by its length and its crisp crust. The French have been baking long sticks of bread for over 200 years; but it was only in 1920 that the current baguette we know and love came into being. Over time, French law has established what is and what is not a baguette. The French are known for their high standards where culinary arts are concerned. To preserve quality in their bread, laws were passed requiring minimum quantities of certain quality ingredients in each loaf of bread. Beginning in 1920 a labor law prevented all workers, bakers too, from starting their day before 4 a.m. Bakers adjusted by shaping their loaves of bread, so they baked more quickly and evenly. As a result, the long, narrow loaves were found to be convenient for slicing and storing. French Bread Day is a great opportunity to indulge in some comfort food at its finest! Serve French bread warm, slathered with butter and a chunk of cheese on the side. Why not embrace the whole continental experience and have a glass of fine French wine with it? Although it is known as French bread, this amazing wonder of chewiness was created in Vienna during the Industrial revolution (1800s), along with steam ovens. Since steam is a huge part of the French Bread process, the steam ovens were important in the process. -

Download a PDF of the Missoula Dining

EAT LIKE A LOCAL Missoula Dining Guide 2021 WE SLOW DOWN AND SAVOR EVERY BITE Where “farm-to-table” is a quicker commute than you might think, and “local” is a given on most menus. This place is Missoula, Montana, and our dining (and drinking) scene DOUBLE FRONT CHICKEN is deliciously unexpected. From downtown distilleries, to midtown mainstays, to traveling food trucks and more, we’ve got something for any occasion and every palate. Bottom line: It’s easy to eat well in Missoula. Culinary tourists can sample new cuisines at every meal and large groups enjoy bus-friendly restaurants as they pass through. We order cocktails and fresh oysters GILD with riverfront views, and sip local brews as we watch live music. Dining in Missoula is an experience in and of itself, and it’s about time you tried it. Missoula’s dining scene is always evolving—find the latest information on restaurants, bars, breweries and more by visiting our website. PLONK 2 2021 MISSOULA DINING GUIDE // DESTINATIONMISSOULA.ORG INSIDE 4 BETTER TOGETHER 6 BIGA PIZZA 8 M-80 CHICKEN 10 MADE IN MISSOULA: ARTHUR WAYNE HOT SAUCE 11 MISSOULA RESTAURANTS 24 FOOD TRUCKS 26 PICNIC LIKE A LOCAL Published by: Destination Missoula Visitor Information Center 101 E. Main St. | Missoula, Montana 406.532.3250 | 800.526.3465 [email protected] destinationmissoula.org #Missoula #VisitMissoula 2021’S HAPPIEST #TheresThisPlace #MissoulaEats CITIES IN AMERICA: Mailing address: MISSOULA, MONTANA 140 N. Higgins Ave., Suite 202 Missoula, Montana 59802 WalletHub 1889 PHOTOS BY TAYLAR ROBBINS 2021 MISSOULA DINING GUIDE // DESTINATIONMISSOULA.ORG 3 BETTER TOGETHER IN MISSOULA Don’t make the mistake of sticking to one restaurant during your visit—Missoula’s local food, brews and other beverages taste even better when paired together with a side of fresh air. -

Bakery & Breads Directory

BAKERY & BREADS DIRECTORY Bakery Breads 2018 - Cover.indd 2 01/10/2018 16:16 WELCOME to the Bakery & Breads Directory Published October 2018 Prices in this brochure correct at time of printing. Subject to market price changes. Confirm current price at time of dispatch. Bakery Breads 2018 - Inside Cover.indd 1 03/10/2018 11:06 Let us INSPIRE YOU Want to develop your menus to offer your customers more? Come and explore the Total Foodservice range as we cook up some of our most relevant product lines for your business and present them in new and innovative ways. Our aim is to send you away with a little seed of inspiration for you to turn into your own menu masterpiece. You can even get hands on and trial the products for yourself in our kitchen, or simply sit back and let us do the work while you have a team meeting with your chefs and managers in our presentation and meeting rooms. OUR FACILITIES Our Clitheroe Depot has a fully fitted kitchen which is light and spacious with a homely feel, giving you and your team plenty of room to experiment with the food. Or sit back and let us demonstrate for you in our adjacent presentation room with viewing/serving window – comfortable for 8 people and opens up to accommodate 16. At our Huddersfield Depot we have a newly fitted training & demonstration kitchen. Join us and let us demonstrate our products and inspire you with new ideas for your menus. We also have a full Barista set up with a cosy space for you to sit and relax. -

Mastering the Art of Bread. Cottage Bakery Baked Artisan Breads and Rolls

MASTERING THE ART OF BREAD. COTTAGE BAKERY BAKED ARTISAN BREADS AND ROLLS. EXPERIENCE BAKED RIGHT IN. FROM PROOF TO PERFECTION, EVERY TIME. • The Cottage Bakery portfolio, synonymous with quality, indulgence and innovation, meets the industry need to produce true, authentic baked artisan breads and rolls • Variety of flavors ranging from savory to sweet • Elevate by topping with seasonings and cheeses TRUE ARTISAN PROCESS. • All-natural dough starter • Long fermentation and proof times • Hand scored • Hearth oven baked on natural stone EXCEPTIONAL TASTE. • Chewy, crisp crust • Moist, open inner crumb • Deliciously complex flavor CONVENIENCE AND FRESHNESS. • Parbaked and flash-frozen to preserve quality • Easily finished in your oven • Saves time and labor AWAKE THE ARTISAN IN YOU. THE ARTISAN BAKERY SINCE 1954 GROWTH OF SPECIALTY TOAST ORDERS, LIKE AVOCADO TOAST, MARKET IS EXPECTED TO GROW 4.1% COTTAGE BAKERY HAS PRACTICED ARTISAN SINCE 2010.2 FROM 2019 TO 2024.1 BREAD BAKING FOR OVER 65 YEARS. 4X 1 Artisan Bakery Market Research Report, Market Research Future, 2020 2 Insider, 2019 Instantly turn any sandwich or burger BAKED into a gourmet offering. ARTISAN • Available in oblong, rectangular or square rolls SANDWICH • Variety of flavors ranging from savory to sweet CARRIERS • Elevate by topping with GO GOURMET. seasonings and cheeses ROASTED GARLIC STEAK SANDWICH ON ARTISAN CIABATTA ROLL An artisan, elevated sub roll crafted with BAKED a thin crust and easier bite. ARTISAN • Perfect for hot or cold deli sandwiches • Sturdy enough for a variety of THIN CRUST condiments BREAD • Easy bite and a soft, moist inner crumb THE PERFECT BITE. PULLED PORK AND SLAW ON THIN CRUST FRENCH DEMI SUB ROLL Elevate bread baskets, sliders or sandwich BAKED offerings with a diverse variety of artisan ARTISAN dinner rolls. -

Hearth Breads

HEARTH BREADS COUNTRY WHEAT FRENCH BATARD SEEDED MULTIGRAIN #0005 #0004 #0006 Each – 1lb 8oz Each – 1lb 8oz Each – 1lb 8oz PUMPKIN CRANBERRY SOURDOUGH ROUND #74 #204 Each – 1lb Each – 1lb 4oz 314.352.4770 | companionbaking.com PAR BAKED BREADS CIABATTA FRENCH BAGUETTE FRENCH EPI #1602 #1603 #1604 CS/15 – 14oz CS/20 – 12oz CS/15 – 1lb KALAMATA OLIVE #1050 CS/15 – 14oz BAVARIAN PRETZELS CAFÉ BAGUETTE ORIGINAL 6-8" STICK 10-12" #784 #785 #786 CS/15 – 1lb CS/48 – 4oz CS/48 – 4oz 314.352.4770 | companionbaking.com SANDWICH BUNS BADA BING – BAVARIAN BRIOCHE ITALIAN SUB 7" PRETZEL SQUARE #90 #976 #0009 Dozen – 3oz Bag/10 – 4.5oz Dozen – 4oz BRIOCHE SLICED LIL (BRIOCHE) WHITE JOHN DOUGH #390 #964 #270 Dozen – 3oz Dozen – 2.2oz Dozen – 3.5oz PEACEMAKER RUSTINA WHOLE WHEAT (PO’ BOY) 8" (CIABATTINI) #960 #971 #433 Dozen – 3.5oz Bag/8 – 4oz Bag/4 – 3.5oz 314.352.4770 | companionbaking.com DELI BREADS We are a family- owned, local St. Louis bakery that places as much care in our MULTIGRAIN PUGLIESE relationships as we do #250 #252 in our products. Each – 2lb 8oz Each – 2lb 8oz We focus on making artisanal breads that are approachable, affordable and accessible so that you can deliver a memorable experience SEEDED NY RYE SOURDOUGH to your customer. #301 #254 Each – 2lb 8oz Each – 2lb 8oz 314.352.4770 | companionbaking.com SANDWICH BREADS BAKEHOUSE WHITE HONEY WHEAT MULTIGRAIN #284 #201 #182 Each – 2lbs Each – 2lbs Each – 2lbs Since we pulled the first baguettes from our oven in 1993, we’ve simply NEW YORK SOURDOUGH tried to do what we do SEEDED RYE #484 the right way.Gentle #188 Each – 2lbs mixing to preserve the Each – 2lbs flavor of the grain. -

November 2012 Monte-Carlo SBM

240 chefs and 300 Michelin stars- an international celebration of the 25 anniversary of Le Louis XV – Alain Ducasse 16 th ,17 th and 18 th of November 2012 Monte-Carlo SBM www.aducasse-25anslouisxv.com 1 PRESS KIT Monaco, November 2012 SUMMARY EDITORIAL p.3 A UNIQUE SUMMIT MEETING p.4 300 STARS AND 240 CHEFS FOR A UNIQUE GATHERING p.4 AN EPHEMERAL MEDITERRANEAN MARKET PLACE, A HIGHLIGHT OF THE EVENT. P.7 THE ALPHABET OF THE 100 MEDITERRANEAN PRODUCTS p.7 A MEETING BETWEEN THE LEADING CHEFS OF THE WORLD & MEDITERRANEAN PRODUCE p.8 LE LOUIS XV- ALAIN DUCASSE p.11 MONTE CARLO SBM p.15 THE PARTNERS OF THE EXCEPTIONAL ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION p.16 INFORMATION AND MEDIA CONTACTS p.18 2 PRESS KIT Monaco, November 2012 EDITORIAL « My centre of gravity remains and will always be cooking. I am thus a happy cook! My inspiration comes from a combination of the Southwest of France, where I grew up and from the Mediterranean, which seduced me from a young age. But I also remain a curious cook. My roots carry me but do not hold me down. My arrival in Monaco was a magical and momentous moment in my life. It is on this rock, nestled between France and Italy that I encountered my Riviera. I know today that this land was my destiny. All my cooking is inspired from this area that sings sunlight. From it, I draw strength and truth. « Riviera »: the word alone echoes a certain invitation to dolce farniente. However, the Riviera is a land of farmers and breeders who, historically, have toiled to bring abundance from an arid land. -

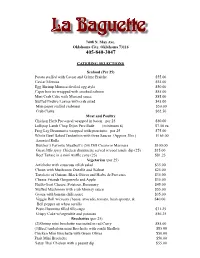

Catering Menu La Baguette Bistro

! 7408 N. May Ave. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73116 405-840-3047 CATERING SELECTIONS Seafood (Per 25) Potato stuffed with Caviar and Crème Fraîche $55.00 Caviar Mimosa $55.00 Egg Shrimp Mimosa deviled egg style $50.00 Caper berries wrapped with smoked salmon $55.00 Mini Crab Cake with Mustard sauce $85.00 Stuffed Endive Leaves with crab salad $45.00 Mini paper stuffed crabmeat $50.00 Crab Claws $62.50 Meat and Poultry Chicken Herb Provencal wrapped in bacon per 25 $50.00 Lollipop Lamb Chop Dijon Percillade (minimum 8) $7.50 ea. Frog Leg Drummette wrapped with prosciutto per 25 $75.00 Whole Beef Baked Tenderloin with three Sauces (Approx 3lbs ) $165.00 Assorted Rolls Butcher’s Favorite Meatball’s (50) Dill Cream or Marinara $100.00 Great little spicy Chicken drummette served w/cool ranch dip (25) $35.00 Beef Tartare in a mini waffle cone (25) $81.25 Vegetarian (per 25) Artichoke with couscous relish salad $35.00 Choux with Mushroom Duxelle and Walnut $25.00 Tartelette of Onions, Black Olives and Herbs de Provence $35.00 Cheese Friands Gorgonzola and Apple $35.00 Phillo Goat Cheese, Potatoes, Rosemary $45.00 Stuffed Mushroom with crab Mornay sauce $55.00 Gyoza with banana chili sauce $35.00 Veggie Roll w/cream cheese, avocado, tomato, bean sprouts, & $40.00 Bell pepper on wheat tortilla Pesto Hummus filled fillo cups $31.25 Crispy Cake w/vegetable and potatoes $56.25 Brochettes (per 25) (2)Shrimp mini brochette marinated in red Curry $85.00 (3)Beef tenderloin mini Brochette with confit Shallots $85.00 Chicken Mini Brochette with Green Olives $50.00 Fruit Mini Brochette $50.00 Satay Thai Chicken with a peanut dip $55.00 Cantaloupe cube wrapped in prosciutto $55.00 Brie En Croute Served with grapes, spicy roasted pecans & toasted almonds. -

Artisan Breads, Buns & Baked Goods

ARTISAN BREADS, BUNS & BAKED GOODS OUR STORY We’re passionate about baking and handcrafing the finest artisan breads in the northwest. Founded in Ketchum, Idaho in 1997, Bigwood Bread is the premiere small-batch artisan bakery in Idaho, and is a multi-generational family-owned business. We have been producing handmade artisan-style crusty dinner breads, sandwich breads, buns, rolls, bagels, pastries, and par-baked products for over 20 years, all of which we’ve developed through use in our own cafés. Our starter was brought here from France and we nurture it for use in most every bread we bake. We distribute 365 days a year to quality restaurants, hotels, and gourmet markets throughout Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, Utah, and the Dakotas. Our breads are handmade using the highest quality, sustainable, and all-natural local grains, milled to our exact standards from family farmers in the Pacific Northwest. Our products contain no artificial ingredients or high fructose corn syrup, and are GMO and preservative-free. Bigwood Bread production is housed in a 10,000 square foot, temperature controlled, FDA inspected facility in Ketchum where we also operate two high volume cafés. Our baking facility was built in 2015 and is a LEED certified green building, the first commercial LEED building in Blaine County, and the only LEED certified bakery in the Pacific Northwest. We’re proud of our dedication to environmental and sustainable business practices. At Bigwood Bread, our commitment to creating delicious baked goods extends beyond our own cafés. We believe in giving back to our community and being environmentally and socially responsible, while producing the highest quality products.