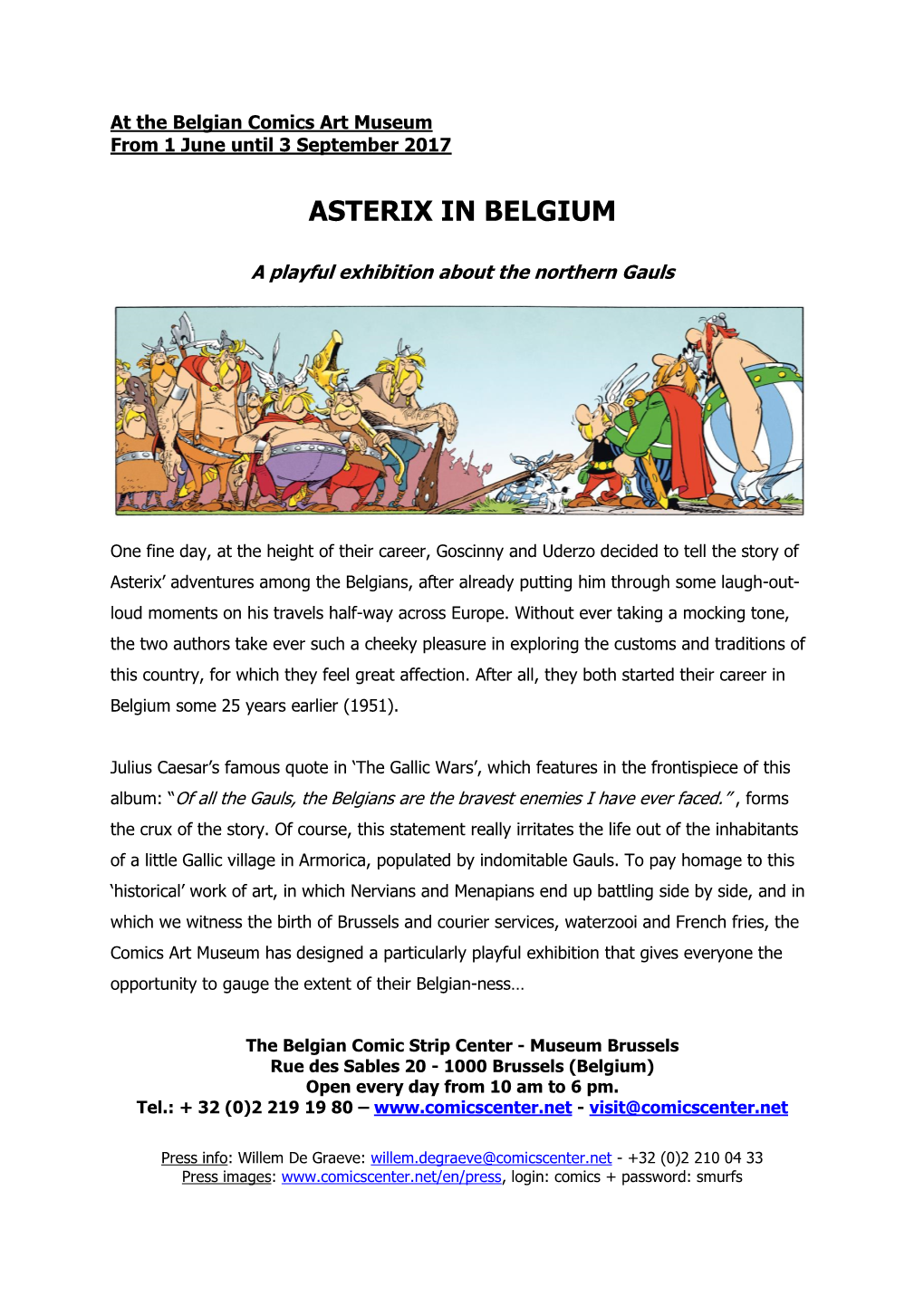

Asterix in Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wholesale Price List

Wholesale Price List All prices exlude GST and are subject to change without prior notice tel: 03 455 9025 email: [email protected] www.afd.co.nz Wholesale Price List Baked Goods - Biscuits/Crackers 11363 Biscuit Crumbs Malt 10Kg C Kayes Pack P.O.A 11360 Biscuit Crumbs Malt 1Kg A Foodfirst Pack $8.80 11361 Biscuit Crumbs Malt 2.5Kg A S/Valley Pack $24.10 11421 Biscuit Crumbs Van Wine 10Kg C Davis Ctn P.O.A 11362 Biscuit Crumbs Vanilla 1Kg A Foodfirst Each $8.88 11367 Biscuit Crumbs Vanilla 2.5Kg A Foodfirst Pack $20.60 11358 Biscuit Malt 250Gm A Griffins Each $4.18 11357 Biscuit Super Wine 250Gm A Griffins Each $4.18 11356 Biscuit Vanilla Wine 250Gm A Griffins Each $4.18 50343 Brownie Choc Fudge G/F 65Gm 16S (6354) L Mrs Higgins Slv $31.05 50329 Cookie Choc Candy 60Gm 20S (310) Frozen L Mrs Higgins Slv $25.30 50336 Cookie Choc Chew 100Gm 15S (651) L Mrs Higgins Box $24.10 50344 Cookie Choc Chip G/F 60Gm 12S (6424) L Mrs Higgins Slv $22.30 50333 Cookie Choc Chunk Chip 100Gm 15S (652) L Mrs Higgins Box $24.10 50331 Cookie Choc Fudge Brownie 80Gm 15S (655) L Mrs Higgins Box $24.70 50345 Cookie Choc Mac 85Gm 15S (653) A Mrs Higgins Slv $28.90 50342 Cookie Chunky Choc Chip 40Gm 25S (722) A Mrs Higgins Slv $27.60 50323 Cookie Dough Anzac 60Gm 81S (208) C Mrs Higgins Box P.O.A 50324 Cookie Dough Chunky Choc Chip 60Gm 81S (213) A Mrs Higgins Box $89.00 50325 Cookie Dough Triple Choc 60Gm 81S (225) A Mrs Higgins Box $89.00 50327 Cookie Dough Vegan Choc Chew 60Gm 81S (240) A Mrs Higgins Box $97.68 50326 Cookie Dough White Choc Mac 60Gm 81S (204) -

Asterix E Obelix Contra Cesar

Asterix E Obelix Contra Cesar 1 / 6 2 / 6 Asterix E Obelix Contra Cesar 3 / 6 When Asterix and Obelix discover what happened, they inform the village, who proceed to attack the garrison.. The film's theme song, Astérix est là, was composed and performed by Plastic Bertrand.. 2Voice CastPlot[edit]To honour Julius Caesar's successful campaigns of conquest, gifts are brought to Rome from across the Roman Empire. 1. asterix obelix contra cesar 2. asterix y obelix contra cesar 3. asterix y obelix contra cesar pelicula completa en español Astérix et la surprise de CésarDirected byGaëtan BrizziPaul BrizziProduced byYannik PielWritten byPierre Tcherniaadapted fromRené GoscinnyAlbert UderzoMusic byVladimir Cosma198579 minutesCountryFrance, BelgiumLanguageFrench / EnglishAsterix Versus Caesar (also known in France as Astérix et la surprise de César) is a 1985 animated film that was written by René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo and Pierre Tchernia, and directed by Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi, and is the fourth film adaptation of the Asterix comic book series.. When Tax collector Claudius Incorruptus does not get his money from the villagers, Julius Caesar himself comes to the place to see what's so special about their resistance.. Directed by: Claude Zidi Produced by: Katharina, Renn Productions Genre: Fiction - Runtime: 1 h 45 min.. Discover (and save!) your own Pins on Pinterest Asterix Et Obelix Mission CleopatreThe well-known little village from the Asterix and Obelix-comic books is in trouble: It is the last place not controlled by Rome. asterix obelix -

Jacques Brel, 25 Jaar Later

JACQUES BREL, 25 JAAR LATER Dat Jacques Brel België’s grootste chansonnier is, zal niemand betwijfelen. Het is zelfs waarschijnlijk dat hij wereldwijd de meest bekende chansonnier uit het Franse taalgebied is. Hij stierf op 9 oktober 1978, een kwarteeuw geleden. Maar zijn ster blijft schitteren aan het chansonfirmament, ook bij ons. Wie was hij? Wat zong hij? Wat gebeurt er nu met zijn oeuvre? Tekst: Dries Delrue groep ‘La Franche Cordée’, opgericht door een die het hem ook onmogelijk heeft gemaakt idealistisch en vrij progressief echtpaar. een normale verhouding met vrouwen te heb- De Franstalige Brusselaar, die zich graag als Alleen al het gemengd karakter van de groep, ben (j’ai l’impression d’être passé à côté). Vlaming uitgaf bij interviews, was nauwelijks jongens en meisjes samen, was toen hoogst Gezien zijn bedroevende resultaten op school 49 toen hij in een Parijs’ ziekenhuis aan kan- uitzonderlijk in katholieke milieus. Ook daar bleek de toekomst van deze burgerzoon in het ker stierf. Ruim 10 jaar eerder had hij al vrij- werden de idealen van rechtvaardigheid, ouderlijk bedrijf te liggen. Maar zoon Jacques willig een einde gemaakt aan zijn carrière als trouw en noem maar op, verder doorgegeven. verlangde enkel uit dat milieu te ontsnappen zanger-performer. Zijn loopbaan als zanger De leuze van de beweging was ‘Plus est en toi’ en geloofde erin een carrière als zanger te duurde nauwelijks 15 jaar. Zijn roem is omge- (Er steekt méér in jou). Daar leerde hij zijn kunnen opbouwen. Zijn vrouw liet hem zijn keerd evenredig met die korte tijd. vrouw Miche kennen en in 1950 huwden ze en gang gaan en ook zijn moeder steunde hem, kregen het jaar daarop een eerste dochter. -

Hergé and Tintin

Hergé and Tintin PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 20 Jan 2012 15:32:26 UTC Contents Articles Hergé 1 Hergé 1 The Adventures of Tintin 11 The Adventures of Tintin 11 Tintin in the Land of the Soviets 30 Tintin in the Congo 37 Tintin in America 44 Cigars of the Pharaoh 47 The Blue Lotus 53 The Broken Ear 58 The Black Island 63 King Ottokar's Sceptre 68 The Crab with the Golden Claws 73 The Shooting Star 76 The Secret of the Unicorn 80 Red Rackham's Treasure 85 The Seven Crystal Balls 90 Prisoners of the Sun 94 Land of Black Gold 97 Destination Moon 102 Explorers on the Moon 105 The Calculus Affair 110 The Red Sea Sharks 114 Tintin in Tibet 118 The Castafiore Emerald 124 Flight 714 126 Tintin and the Picaros 129 Tintin and Alph-Art 132 Publications of Tintin 137 Le Petit Vingtième 137 Le Soir 140 Tintin magazine 141 Casterman 146 Methuen Publishing 147 Tintin characters 150 List of characters 150 Captain Haddock 170 Professor Calculus 173 Thomson and Thompson 177 Rastapopoulos 180 Bianca Castafiore 182 Chang Chong-Chen 184 Nestor 187 Locations in Tintin 188 Settings in The Adventures of Tintin 188 Borduria 192 Bordurian 194 Marlinspike Hall 196 San Theodoros 198 Syldavia 202 Syldavian 207 Tintin in other media 212 Tintin books, films, and media 212 Tintin on postage stamps 216 Tintin coins 217 Books featuring Tintin 218 Tintin's Travel Diaries 218 Tintin television series 219 Hergé's Adventures of Tintin 219 The Adventures of Tintin 222 Tintin films -

Doniol-Valcroze, Est Un Hymne À La Sensualité

LE CHÂTEAU DE LA VOLUPTÉ Dès les premiers plans, on se laisse griser par la mélopée envoûtante de Gainsbourg qui accompagne la découverte des lieux : un château baroque et délicieusement décadent du Roussillon où se concentre l'action. Peu à peu, on fait la connaissance des personnages qui, comme chez Renoir, se partagent en deux catégories : grands-bourgeois et domestiques. L'eau à la bouche, premier long métrage de Doniol-Valcroze, est un hymne à la sensualité. Maniant l'ironie à merveille, le cinéaste orchestre pourtant la rencontre entre ses protagonistes dans un contexte funeste : la disparition de la châtelaine et l'exécution tes- tamentaire de ses dernières volontés. Mais la raideur compassée des débuts ne tarde pas à céder le pas à une fantaisie bienvenue… L'atmosphère méridionale et le cadre enchanteur invitent à la paresse et à l'abandon. Désœuvrés, mais encore empêchés par leur éducation bourgeoise, les héritiers et le notaire s'engagent dans un charmant marivaudage qui finit par vaincre leurs dernières résistances. Comme dans un miroir déformant qui leur est tendu, César, le majordome, ne s'embarrasse pas de conventions : il assume son désir de recruter les femmes de chambre dans le seul but de les séduire et poursuit de ses assiduités la jeune - et bien nommée - Prudence (Bernadette Lafont, mutine et aguicheuse à souhait). On sent bien que les grands-bourgeois, qui observent la parade amoureuse de César l'œil amusé, envient ce garçon simple qui s'autorise à obéir à ses pulsions. Mais le personnage principal de ce film solaire réalisé en 1959, année qui donne le coup d'envoi à la Nouvelle Vague, reste le château tout droit sorti d'un conte à la Perrault. -

Chapter One Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Reading books can be one of the choices for some people to spend their spare time. There are some kinds of book; they are novel, biography, poetry, drama, comics, etc. They have their own styles; however, the one that I find most interesting is comics. Comics can be described as “a form of visual art consisting of images which are commonly combined with text often in the form of speech balloons or image captions” <http: www.answers.com>. I like the way how the story of a comic is presented in frames and how the utterances are presented in the speech balloons. Moreover, I like the pictures and the language which is simpler to understand. I like to read comics especially funny comics. I like comics which have funny story, funny pictures and witty language. Usually we say that comics are funny because of the story, but actually, we can say that a comic is funny not only from the story itself, but also from the picture of the comic, or the witty language or speech that is used in the story. Maranatha Christian University 1 Wittiness is the ability to say or write clever, amusing things (Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary 2005: 1755). There are a lot of ways to make witty language; one of them is by using language play. Language play is ‘an action of manipulating the language by bending and breaking its rules’ (Crystal, 1998: 1). We can find a lot of language play in comic books. -

Rene Goscinny WHERES ASTERIX

Goscinny was reared and educated in Buenos Aires and later worked on children’s books in New York City. In 1954 he returned to Paris to direct a press agency and soon became a writer for the “Lucky Luke” comic strip. In (14 August 1926 – 5 November 1977) 1957 he met Uderzo, a cartoonist, and collaborated with him on the short-lived “Benjamin et Benjamine” and, a year later, on the somewhat more successful “Oumpah-Pah le Peau-Rouge” (“Oumpah-Pah the Redskin”). In 1959 Goscinny founded the French humour magazine Pilote, and at the same time, in collaboration with Uderzo, began publishing “Astérix le Gaulois,” a comic strip that concerned itself with the adventures of a diminutive Gallic tribesman at the time of Caesar’s conquest of Gaul. The title character, Astérix, and his friend Obélix belonged to the only unconquered tribe, the “Invincible Gauls.” The Romans they opposed were generally made to look stupid and clumsy. Coinciding as it did with Charles de Gaulle’s rise to power in France, the strip reflected certain political sentiments that were widespread at the time. “Astérix le Gaulois” became widely popular and brought substantial success to both Goscinny and Uderzo. Goscinny was the scriptwriter of several other French comic strips, including “Les Dingodossiers” (1965–67), with Marcel Gotlib, and also was a principal in a French publishing firm. He was made a Chevalier of Arts and Letters in 1967. The “Astérix” strip was translated into 15 languages, and after its appearance in book form (1959) it sold more than 18,000,000 copies world- wide. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

EN ÎLE-DE-FRANCE a Dans « aden » : tout le cinéma et une sélection de sorties Demandez notre supplément www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17485 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE JEUDI 12 AVRIL 2001 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Plans Londres : la monarchie minée par ses « affaires » sociaux b Le gouvernement britannique, le Parlement et la presse s’interrogent sur la fortune des Windsor a Les socialistes b Ils s’inquiètent du mélange entre les activités financières et les devoirs d’Etat veulent faire payer de la famille royale b Les « royals » pourraient être assujettis à un « code de bonne conduite » davantage C’EST UNE AFFAIRE D’ÉTAT dre des documentaires filmés sur… qui, au Royaume-Uni, ébranle, un les familles royales. Elle attirait, les entreprises peu plus, l’institution de la monar- enfin, l’attention sur l’étonnante for- chie. Cette fois, la famille Windsor tune de la Maison Windsor. qui licencient n’est pas déstabilisée par les aven- Le chancelier de l’Echiquier, Gor- tures sentimentales de l’un de ses don Brown, a critiqué les jeunes a membres. C’est plus grave. Elle est Windsor. A la Chambre, une motion Robert Hue critiquée – à la Chambre des com- a été déposée pour exiger des mem- munes, au gouvernement, dans la bres de la famille royale qu’ils demande presse – pour une vilaine affaire d’ar- suivent l’exemple des parlemen- FESTIVAL l’interdiction gent. Le scandale provoqué par les taires en rendant publics leurs reve- propos tenus par la comtesse de nus dans un « registre des intérêts des « licenciements Wessex, née Sophie Rhys-Jones, royaux ». -

Dossier De Presse

VILLE DE SAINT-BRICE-SOUS-FORÊT /// DOSSIER DE PRESSE /// Concert : hommage à Jacques Brel © Alain Marouani Dimanche 24 novembre 2019 à 16 h Le Palladium, 37 rue de Piscop à Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt Contact presse : Sandrine Fanelli /// Directrice de la Communication Tél. : 01 34 29 42 57 /// [email protected] Hommage au grand Jacques Ne me quitte pas, Amsterdam, Ces gens-là, Quand on n’a que l’amour, Les bourgeois… Autant de titres inoubliables de Jacques Brel que reprendront Moïse Melende et Franck Willekens le dimanche 24 novembre au Palladium à Saint- Brice-sous-Forêt. Durant deux heures, ils se prête- ront au jeu périlleux de revisiter les chansons de ce monument de la chanson française (même si comme Adamo, Arno, Lio ou Axelle Red, Maurane… il était belge). © Alain Marouani Des arrangements reggae, funk ou blues apporteront une couleur nouvelle à ces morceaux mille fois entendus. Ils seront ainsi accompagnés d’Olivier Picard (batterie), Massimo Murgia (basse) et Vincent Pagès (piano). Un évènement organisé par la Direction de la Culture, du Sport, des Loisirs et de l’ Animations seniors. Tarifs • 5 € pour les habitants de Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt • 7 € hors commune Rens. et réservations obligatoires : 01 39 33 01 85 ou [email protected] Extrait du spectacle Vous pouvez voir un extrait du concert hommage à Jacques Brel (capture vidéo réalisée à Jaux, près de Compiègne, le 18 janvier dernier) sur la plateforme YouTube : https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=vvSloe8J9tc&feature=youtu.be Moïse Melende \\\ biographie Ingénieur en conseil informatique et diplômé de maîtrise en physique énergétique, Moïse Melende est passionné de musique et de chant gospel depuis sa jeunesse. -

L I B R a I R I E W a L D

Librairie Walden Hervé & Éva Valentin [email protected] l i b r a i r i e w a l d e n 43 Pour saluer la Cinémathèque française –l’invité d’honneur du salon du livre rare devant se tenir du jeudi 17 au dimanche 20 septembre prochains –, nous vous proposons ce catalogue thématique n° 43 en lien avec le septième art. Les livres et documents qui y sont réunis seront, au côté de nombreux autres, présentés en exclusivité au Grand Palais, où nous serons heureux de vous accueillir pour vous les faire découvrir. LISTE DES PRIX N° 43 1 Pagnol 9000 47 Simenon & Simon 100 93 Betty 30 2 Fauchois 300 48 Pagnol 800 94 Harry Potter… 300 3 Dabit 9000 49 Welles 100 95 Tous les matins… 30 4 Pagnol 600 50 Welles 250 96 Marius 80 5 Pagnol 1200 51 Cuny 300 97 César 80 6 Pagnol 1000 52 Chaplin 1000 98 Topaze 100 7 Arnaud 5000 53 Les Misérables 4000 99 La Douceur de vivre 30 8 Aymé 5000 54 J’irai cracher… 2000 100 Les Anarchistes 30 9 Boulle 12000 55 Les Tripes au soleil 600 101 Alphaville 40 10 Williams 800 56 À l’aube… 1000 102 Passion 30 11 Pergaud 18000 57 Le Facteur… 500 103 Prénom Carmen 30 12 Roché 10000 58 Au hasard Baltazar 6000 104 Détective 30 13 Merle 7000 59 Truffaut 3000 105 Je vous salue, Marie 30 14 Schoendoerffer 900 60 Z 5000 106 Tout va bien 30 15 Boulle 10000 61 Oury 900 107 Numéro deux 50 16 Merle 1000 62 Barbera 4000 108 Masculin féminin 50 17 Eco 400 63 Arletty 50 109 La possibilité… 30 18 Quignard 5000 64 Bacall 150 110 Le Paradis… 50 19 Duras 4000 65 Bardot 80 111 Les Ennemis 30 20 Le Chien jaune 2200 66 Binoche 150 112 Die -

Langage Expressif Dans Les Chansons Choisies De Jacques Brel

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Pedagogická fakulta Katedra francouzského jazyka a literatury Klára Paseková Langage expressif dans les chansons choisies de Jacques Brel Český název: Výrazové prostředky ve vybraných písních J. Brela Bakalářská práce Praha 2011 Vedoucí bakalářské práce: PhDr. Eva Müllerová, CSc. Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci s názvem « Langage expressif dans les chansons choisies de Jacques Brel » vypracovala samostatně pod vedením PhDr. Evy Müllerové, CSc., s použitím literatury, uvedené na konci mé bakalářské práce v seznamu použité literatury. V Praze 17. 6. 2011 Tato práce by nemohla vzniknout bez lidské a odborné pomoci PhDr. Evy Mullerové, CSc., které bych tímto chtěla moc poděkovat. Abstrakt Výrazové prostředky ve vybraných písních J. Brela V práci poukazujeme na gramatické jevy v písních Amaterdam, Ces gens-là a Vivre debout, které se stavají pro tohoto autora typickými, a to jak vzhledem k frekvenci, tak k vymezení gramatické role. Analýzou jazykových prostředků v textech písní Brela (uváděcích slovesných výrazů, vztažných zájmen qui/que a spojek) je možné dojít k závěru, že jsou záměrně použity a jako takové se opakují v jednotlivých modelech. Brel tyto výrazy staví převážně na začátek verše, čímž navodí subjektivní pořádek věty a tyto výrazy se následně stavají stylově příznakovými. Brel rovněž užívá tyto gramatické prostředky, aby umocnil svůj osobitý projev a zformuloval ho k závěrečnému hudebnímu projevu. V celém textu se projevuje postupná gradace, na níž se podílejí jednotlivé gramatické jevy. Závěrem lze konstatovat, že všechny tyto zvolené gramatické prostředky mají u Brela svoji roli a jsou nepostradatelné pro « brelovské » vyznění písňových textů. Abstract Means of Expression Used in Selected J. -

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order Abe, H. 28 (8) 1993-1999 Bernstein, G. 1 1998 Abe, M. 1 (1) 1994 Bettelheim, E. 1 (1) 2000 Abraham, M. 3 (3) 1999 Bickel, W. 443 1995-2010 Aikman, G. C. L. 4 1994-1998 Biggs, J. 1 2001 Akiyama, M. 16 (10) 1989-1999 Bigourdan, G. 1 1894 Albitskij, V. A. 10 1923-1925 Billings, G. W. 6 1999 Aldering, G. 4 1982 Binzel, R. P. 3 1987-1990 Alikoski, H. 13 1938-1953 Birkle, K. 8 (8) 1989-1993 Allen, E. J. 1 2004 Birtwhistle, P. 56 2003-2009 Allen, L. 2 2004 Blasco, M. 5 (1) 1996-2000 Alu, J. 24 (13) 1987-1993 Block, A. 1 2000 Amburgey, L. L. 2 1997-2000 Boattini, A. 237 (224) 1977-2006 Andrews, A. D. 1 1965 Boehnhardt, H. 1 (1) 1993 Antal, M. 17 1971-1988 Boeker, A. 1 (1) 2002 Antolini, P. 4 (3) 1994-1996 Boeuf, M. 12 1998-2000 Antonini, P. 35 1997-1999 Boffin, H. M. J. 10 (2) 1999-2001 Aoki, M. 2 1996-1997 Bohrmann, A. 9 1936-1938 Apitzsch, R. 43 2004-2009 Boles, T. 1 2002 Arai, M. 45 (45) 1988-1991 Bonomi, R. 1 (1) 1995 Araki, H. 2 (2) 1994 Borgman, D. 1 (1) 2004 Arend, S. 51 1929-1961 B¨orngen, F. 535 (231) 1961-1995 Armstrong, C. 1 (1) 1997 Borrelly, A. 19 1866-1894 Armstrong, M. 2 (1) 1997-1998 Bourban, G. 1 (1) 2005 Asami, A. 7 1997-1999 Bourgeois, P. 1 1929 Asher, D.