A Content Analysis of Xi Jinping's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

China in 2018 Presidents, Politics, and Power

Manuscript version: Published Version The version presented in WRAP is the published version (Version of Record). Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/114518 How to cite: The repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing citation guidance from the publisher. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications SHAUN BRESLIN China in 2018 Presidents, Politics, and Power ABSTRACT President Xi Jinping dominated the Chinese stage during 2018, continuing to con- solidate his power as the CCP sought to reassert its primacy. China flexed its muscles as a great power in a pitch for global leadership. Xi pushed constantly to portray China as the promoter of an open global economy, even as his own continued to slow incrementally amid the widening trade war with the US. -

China's Domestic Politics and Foreign Policy After the 19Th Party Congress

China's Domestic Politics and Foreign Policy after the 19th Party Congress Paper presented to Japanese Views on China and Taiwan: Implications for U.S.-Japan Alliance March 1, 2018 Center for Strategic & International Studies Washington, D.C. Akio Takahara Professor of Contemporary Chinese Politics The Graduate School of Law and Politics, The University of Tokyo Abstract At the 19th Party Congress Xi Jinping proclaimed the advent of a new era. With the new line-up of the politburo and a new orthodox ideology enshrined under his name, he has successfully strengthened further his power and authority and virtually put an end to collective leadership. However, the essence of his new “thought” seems only to be an emphasis of party leadership and his authority, which is unlikely to deliver and meet the desires of the people and solve the contradiction in society that Xi himself acknowledged. Under Xi’s “one-man rule”, China’s external policy could become “soft” and “hard” at the same time. This is because he does not have to worry about internal criticisms for being weak-kneed and also because his assertive personality will hold sway. Introduction October 2017 marked the beginning of the second term of Xi Jinping's party leadership, following the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the First Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the CCP. Although the formal election of the state organ members must wait until the National People's Congress to be held in March 2018, the appointees of major posts would already have been decided internally by the CCP. -

Xi Jinping Stands at the Crossroads What the 19Th Party Congress Tells Us

Li-wen Tung Xi Jinping Stands at the Crossroads What the 19th Party Congress Tells Us Prospect Foundation 2018 PROSPECT FOUNDATION Xi Jinping Stands at the Crossroads What the 19th Party Congress Tells Us Author: Li-wen Tung(董立文) First Published: March 2018 Prospect Foundation Chairman: Tan-sun Chen, Ph.D.(陳唐山) President: I-chung Lai, Ph.D.(賴怡忠) Publishing Department Chief Editor: Chung-cheng Chen, Ph.D.(陳重成) Executive Editor: Julia Chu(朱春梅) Wei-min Liu(劉維民) Editor: Yu-chih Chen(陳昱誌) Published by PROSPECT FOUNDATION No. 1, Lane 60, Sec. 3, Tingzhou Rd., Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C. Tel: 886-2-23654366 This article is also available online at http://www.pf.org.tw All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-986-89374-6-8 Prospect Foundation The Prospect Foundation (hereafter as the Foundation), a private, non-profit research organization, was founded on the third of March 1997 in Taipei in the Republic of China on Taiwan. Strictly non-partisan, the Foundation enjoys academic and administrative independence. The Foundation is dedicated to providing her clients government agencies, private enterprises and academic institutions with pragmatic and comprehensive policy analysis on current crucial issues in the areas of Cross-Strait relations, foreign policy, national security, international relations, strategic studies, and international business. The Foundation seeks to serve as a research center linking government agencies, private enterprises and academic institutions in terms of information integration and policy analysis. -

Mainstream Cinema As a Tool for China's Soft Power

Master’s Degree programme in Languages, Economics and Institutions of Asia and North Africa “Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004)” Final Thesis Mainstream cinema as a tool for China’s soft power Supervisor Ch. Prof. Federico Alberto Greselin Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Tiziano Vescovi Graduand Alessia Forner Matriculation Number 846622 Academic Year 2017 / 2018 To the two stars that have guided me from above TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 5 Chapter one: Soft power: a general overview and the beginning of China’s soft power era 7 1.1 Joseph Nye’s definition of soft power 7 1.2 Culture: the core of soft power 10 1.3 The entry of the concept of soft power in China and its translations 12 1.4 Hu Jintao’s speech at the 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China and China’s first steps towards its soft power strategy 14 Chapter two: China’s focus on cultural soft power and the Chinese film industry 19 2.1 China’s investments in the film industry and films as a soft power resource 19 2.2 The situation of the Chinese film industry in the 1980s and 1990s: is Hollywood China’s lifeline? 26 2.3 Main melody films and the correlation with the China dream (( : taking the documentary Amazing China ()() and the film American Dreams in China (() as an example 32 2.4 Focus on the film Wolf Warrior II II) : a successful soft power strategy 56 Chapter three: Sino-US collaborations 65 3.1 Hollywood and China: same bed, different dreams 65 3.2 The different types of collaborations between China and Hollywood 69 3.3 Is China changing Hollywood? 78 -

2016 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC 2016)

2016 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC 2016) Yinchuan, China 28-30 May 2016 Pages 1-625 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1651D-POD ISBN: 978-1-4673-9715-5 1/11 Copyright © 2016 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc All Rights Reserved Copyright and Reprint Permissions: Abstracting is permitted with credit to the source. Libraries are permitted to photocopy beyond the limit of U.S. copyright law for private use of patrons those articles in this volume that carry a code at the bottom of the first page, provided the per-copy fee indicated in the code is paid through Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. For other copying, reprint or republication permission, write to IEEE Copyrights Manager, IEEE Service Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854. All rights reserved. ***This publication is a representation of what appears in the IEEE Digital Libraries. Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1651D-POD ISBN (Print-On-Demand): 978-1-4673-9715-5 ISBN (Online): 978-1-4673-9714-8 ISSN: 1948-9439 Additional Copies of This Publication Are Available From: Curran Associates, Inc 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: (845) 758-0400 Fax: (845) 758-2633 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com Technical Papers Session SatA01: Adaptive Control (I) Date/Time Saturday, 28 May 2016 / 13:30-15:30 Venue Room 01 Chair Wei Wang, Beihang Univ. Co-Chair Shicong Dai, Beihang Univ. 13:30-13:50 SatA01-1 Neural-based adaptive output-feedback control for a class of nonlinear systems 1 Honghong Wang, Qingdao Univ. -

Chapter 2 Beijing's Internal and External Challenges

CHAPTER 2 BEIJING’S INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CHALLENGES Key Findings • The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is facing internal and external challenges as it attempts to maintain power at home and increase its influence abroad. China’s leadership is acutely aware of these challenges and is making a concerted effort to overcome them. • The CCP perceives Western values and democracy as weaken- ing the ideological commitment to China’s socialist system of Party cadres and the broader populace, which the Party views as a fundamental threat to its rule. General Secretary Xi Jin- ping has attempted to restore the CCP’s belief in its founding values to further consolidate control over nearly all of China’s government, economy, and society. His personal ascendancy within the CCP is in contrast to the previous consensus-based model established by his predecessors. Meanwhile, his signature anticorruption campaign has contributed to bureaucratic confu- sion and paralysis while failing to resolve the endemic corrup- tion plaguing China’s governing system. • China’s current economic challenges include slowing econom- ic growth, a struggling private sector, rising debt levels, and a rapidly-aging population. Beijing’s deleveraging campaign has been a major drag on growth and disproportionately affects the private sector. Rather than attempt to energize China’s econo- my through market reforms, the policy emphasis under General Secretary Xi has shifted markedly toward state control. • Beijing views its dependence on foreign intellectual property as undermining its ambition to become a global power and a threat to its technological independence. China has accelerated its efforts to develop advanced technologies to move up the eco- nomic value chain and reduce its dependence on foreign tech- nology, which it views as both a critical economic and security vulnerability. -

“China's Digital Authoritarianism: Surveillance, Influence, And

“China’s Digital Authoritarianism: Surveillance, Influence, and Political Control” May 16, 2019 Hearing Before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence Prepared statement by Peter Mattis Research Fellow, China Studies Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation * * * I. OVERVIEW Chairman Schiff, Ranking member Nunes, distinguished members of the Committee, thank you for inviting me to appear before you. The Chinese Communist Party’s influence and, particularly, its political interference in the United States is an important topic as we establish a new baseline for U.S.-China relations. Any sustainable, long-term strategy for addressing China’s challenge requires the integrity of U.S. political and policymaking processes. This requires grappling with the challenges posed by the party’s efforts to shape the United States by interfering in our politics and domestic affairs. The United States, its political and business elite, its thinkers, and its Chinese communities have long been targets for the Chinese Communist Party. The party employs tools that go well beyond traditional public diplomacy efforts. Often these tools lead to activities that are, in the words of former Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, corrupt, covert, and/or coercive. Nevertheless, many activities are not covered by Turnbull’s three “Cs” but are still concerning and undermine the ability of the United States to comprehend and address Beijing’s challenge. Here are a few of the ways in which the Chinese Communist Party has shaped the ways in which Americans discuss, understand, and respond to the People’s Republic of China, its rise, and its activities: ● We have been persuaded that the Chinese Communist Party is not ideological and has substituted its Leninist tradition for a variation of capitalism. -

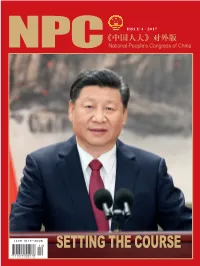

Setting the Course

ISSUE 4 · 2017 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China SETTING THE COURsE General Secretary Xi Jinping (1st L) and other members of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the 19th CPC Central Committee Li Keqiang (2nd L), Li Zhanshu (3rd L), Wang Yang (4th L), Wang Huning (3rd R), Zhao Leji (2nd R) and Han Zheng (1st R), meet the press after being elected on Octo- ber 25, 2017. Ma Zhancheng SPECIAL REPORT 6 New CPC leadership for new era Contents 19th CPC National Congress Special Report In-depth 28 6 26 President Xi Jinping steers New CPC leadership for new era Top CPC leaders reaffirm mission Chinese economy toward 12 at Party’s birthplace high-quality development Setting the course Focus 20 Embarking on a new journey 32 National memorial ceremony for 24 Nanjing Massacre victims Grand design 4 NATIONAL PeoPle’s CoNgress of ChiNa NPC President Xi Jinping steers Chinese 28 economy toward high-quality development 37 National memorial ceremony for 32 Nanjing Massacre victims Awareness of law aids resolution ISSUE 4 · 2017 36 Legislation Chairman Zhang Dejiang calls for pro- motion of Constitution spirit 44 Encourage and protect fair market 38 competition China’s general provisions of Civil NPC Law take effect General Editorial Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, Xicheng District Beijing 39 100805,P.R.China Tibetan NPC delegation visits Tel: (86-10)6309-8540 Canada, Argentina and US (86-10)8308-3891 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of ISSN 1674-3008 Supervision China (CPC), speaks when meeting the press at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Oc- CN 11-5683/D tober 25, 2017. -

Peppa Pig Latest Victim of China Censors

MASS DRIVES SOARING REAL MADRID ADDS TO ITS GAMING REVENUES LE FRENCH EUROPEAN DOMINANCE Casino revenue rocketed Two-time defending champion past even the most bullish PIANISTS OPEN Madrid will be playing its expectations in April, MAY FESTIVAL fourth Champions League final soaring 28 percent in five years P2 ANALYSIS P3 EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW P19 THU.03 May 2018 T. 25º/ 31º C H. 70/ 98% facebook.com/mdtimes + 11,000 MOP 8.00 3039 N.º HKD 10.00 FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” WORLD BRIEFS RENATO MARQUES RENATO AP PHOTO CHINA The Dominican Republic has established diplomatic relations with China, breaking ties with Beijing’s rival Taiwan in the latest blow to the self-ruled island democracy China has been trying to isolate on the global stage. THAILAND A court in southern Thailand has sentenced six men to death for several bombings in 2016 that killed two people and wounded more than 20, an army spokesman said yesterday. More on p13 AP PHOTO Mayday for freedom KOREA The rival Koreas have dismantled huge loudspeakers used to blare Cold War-style P5,7 propaganda across their of demonstration tense border, as South Korea’s president asked the United Nations to observe the North’s AP PHOTO planned closing of its nuclear test site. More on p12 Suspected militants Peppa Pig latest INDIA shot and killed three men in Indian-controlled Kashmir, police said, as the disputed region victim of China observed a strike to protest the killing of two rebels and a civilian this P11 week during an Indian censors counterinsurgency operation. -

Images of Foreign Countries on Chinese Social Media: a Comparative Study of State Accounts and Private Accounts on the Wechat Official Account Platform

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford Images of Foreign Countries on Chinese Social Media: A Comparative Study of State Accounts and Private Accounts on the WeChat Official Account Platform by Zijuan Zhong September 2019 Michaelmas Term 2018 and Hilary Term 2019 Sponsor: Thomson Reuters Foundation Order of Contents Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction……………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 The Rise of WeChat Official Accounts (WCOAs) ……………………………………………………………….. 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Media Attention to Foreign News…………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Geographic Distribution of Foreign Coverage…………………………………………………………………... 9 Foreign News Framing……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 11 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Results………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 16 Proportion of Foreign News Coverage……………………………………………………………………………… 16 Countries Mentioned……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 19 News Topics…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 Tones about Foreign Countries…………………………………………………………………………………………. 26 Tones about China……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 30 Conclusion and Discussion……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 32 References……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 33 Table 1: Proportion of Foreign News Coverage…………………………………………………………………………….. 17 Table 2: Ten Most Foreign Concentrated WCOAs…………………………………………………………………………. 18 Table -

Standing Committee (In Rank Order) Remaining Members from the 18Th Central Committee Politburo

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) 19th Central Committee Politburo Standing Committee (in rank order) Remaining members from the 18th Central Committee Politburo New members to the 19th Central Committee Politburo The Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) is comprised of the CCP’s top- ranking leaders and is China’s top decision-making body within the Politburo. It meets more frequently and often makes XI JINPING LI KEQIANG LI ZHANSHU WANG YANG WANG HUNING ZHAO LEJI HAN ZHENG key decisions with little or no input from 习近平 李克强 栗战书 汪洋 王沪宁 赵乐际 韩正 the full Politburo. The much larger Central President; CCP General Premier, State Council Chairman, Chairman, Director, Office of CCP Secretary, CCP Central Executive Vice Premier, Secretary; Chairman, CCP Born 1953 Standing Committee of Chinese People’s Political Comprehensively Deepening Discipline Inspection State Council Committee is, in theory, the executive Central Military Commission National People’s Congress Consultative Conference Reform Commission Commission Born 1954 organ of the party. But the Politburo Born 1953 Born 1950 Born 1955 Born 1955 Born 1957 exercises its functions and authority except the few days a year when the Members (in alphabetical order) Central Committee is in session. At the First Session of the 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018, Wang Qishan was elected as the Vice President of China. The vice presidency enables Wang to be another important national leader without a specific party portfolio. But in China’s official CCP pecking order, CAI QI CHEN MIN’ER CHEN